Painting their land

Congolese art is recovering from its lowest days, But paint and canvas for Congolese artists often still have to be brought in the luggage of foreign patrons

Sep 14th 2017

JOSEPH KINKONDA, one of the most famous artists in the Democratic Republic of Congo, lives in a dank bedroom in Ndjili, a scrubby neighbourhood of Kinshasa. At the end of his bed sits a plate with a few balls of paint wrapped in plastic. The air-conditioning unit is broken; a single bare light bulb hangs from the ceiling. Mr Kinkonda, who goes by his pen name of Chéri Chérin, seems as worn down as the surroundings. His legs are swollen; his belly barely covered by a shirt that is as dirty as it is shiny. Yet when he speaks, this miserable studio comes alive.

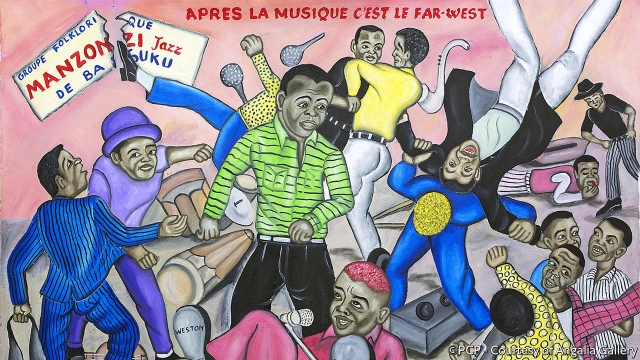

“I was born with drawing,” he announces. “I did not learn it. I had it in my blood.” Born in 1955, he recounts how his father wanted him to become a priest and sent him to a Jesuit seminary. But sensing that his passion was not for religion, the Jesuits sent him to Kinshasa’s Académie des Beaux-Arts instead. On finishing he started drawing huge murals on shop walls. Today he is the leader of a collective of a dozen or so painters. In the courtyard outside the studio his paintings stand in the sun, to be viewed by passers-by. They depict daily life in Congo in an almost cartoonish style, with a vicious satirical touch. One shows an overloaded truck stuck on a mud road, with the caption “wait until when?”

Congolese painting has an illustrious history. As early as 1929, under Belgian colonialism, an exhibition of watercolours by Albert Lubaki, a painter, caused a sensation at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Coco Chanel was a notable early collector. After independence, under the late dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who advocated an ideology of African

authenticité, Congolese artists also benefited from the state’s patronage. Even today, in the filthy mega-city of Kinshasa, remnants of that era remain in the form of impressive public sculptures and murals on public buildings.

Yet recent decades have been less generous. At the end of the cold war, Mobutu’s kleptocratic patronage ran out, along with state funds for almost everything else. In 1994 the academy in Kinshasa closed down as students joined pro-democracy strikes against the regime. And in 1997 a ragtag rebel army sponsored by Rwanda and Uganda marched across the Congo basin and into the capital, at the start of a war which in some parts of the country has yet to end. Art continued: Jean Pigozzi, the heir to a French motoring fortune, supported more than a few painters. But making a living became much harder, says Franck Dikisongele, an artist and curator.

Today, however, Congolese art, like painting across much of Africa, is reviving. As before much of the impetus has come from outside. In 2015 an exhibition took place in Paris that brought many Congolese artists to attention in the West. One new collector is Sindika Dokolo, a Congolese businessman who is the husband of an Angolan, Isabel dos Santos, reputedly Africa’s richest woman. But even within Congo, some patrons have emerged. Trust Merchant Bank, one of Congo’s biggest, hosts an impressive gallery in its head offices in Kinshasa, and sponsors exhibitions. The best hotels in the city feature a growing number of Congolese works.

Artists in Congo tend to deal with real life, rather than abstractions. Art, says, Papy Malambu, who paints expressionist portraits of working men, is “a mirror for all of the world”. Mr Kinkonda’s school, which he calls “popular art”, focuses on street scenes. Others deal more directly with the tragedy of war. Freddy Tsimba creates elaborate sculptures out of found pieces of metal, including used cartridge cases gathered from battlefields.

Mr Malambu says he likes to paint men pulling carts as a reminder to Congo’s big men of what real work is. Mr Kinkonda inserts hidden satirical messages into his street scenes: a dog surrounded by objects refers to a proverb that ultimately hints at the uselessness of politicians. Mr Tsimba’s sculptures include one of a life-size car being pushed along by figures made from spoons. The car represents Congo, moved by its people and driven by a politician who refuses to start the engine.

Unfortunately, unlike music, Congo’s other big cultural export, art does not tend to pay. Though some Congolese paintings have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars overseas, many accomplished Congolese artists still live in poverty. “It is mostly expatriates, the whites, who buy. We Congolese cannot buy because there is no money,” says Hyppolite Benga Nzau, who goes by Chéri Benga (and whose work appears below). Mr Malambu reckons he does well to sell a few paintings a year, typically for a few hundred dollars each. Most artists work out of slum studios or, in the case of one collective of young painters, out of an abandoned, dilapidated building. Materials such as paint and canvas often still have to be brought in the luggage of foreign patrons.

What does the future hold for Congo’s artists? For all their success abroad, the political situation at home grows ever more tense. Despite his second and supposedly final term running out last December, Joseph Kabila, the president, remains in office. New conflict has displaced roughly 1m more people in the past year. If the unrest spreads to the capital, the artistic renaissance could be arrested again. Yet, says Sam Ilus, one of Mr Kinkonda’s protégés, “there is always hope. We live today because we know that we will live tomorrow. Eventually, things always change.”

This article appeared in the Middle East and Africa section of the print edition under the headline "Painting their land"

Painting their land

to the rest of Africa.

to the rest of Africa.