You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Russia's Invasion of Ukraine (Official Thread)

- Thread starter newarkhiphop

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

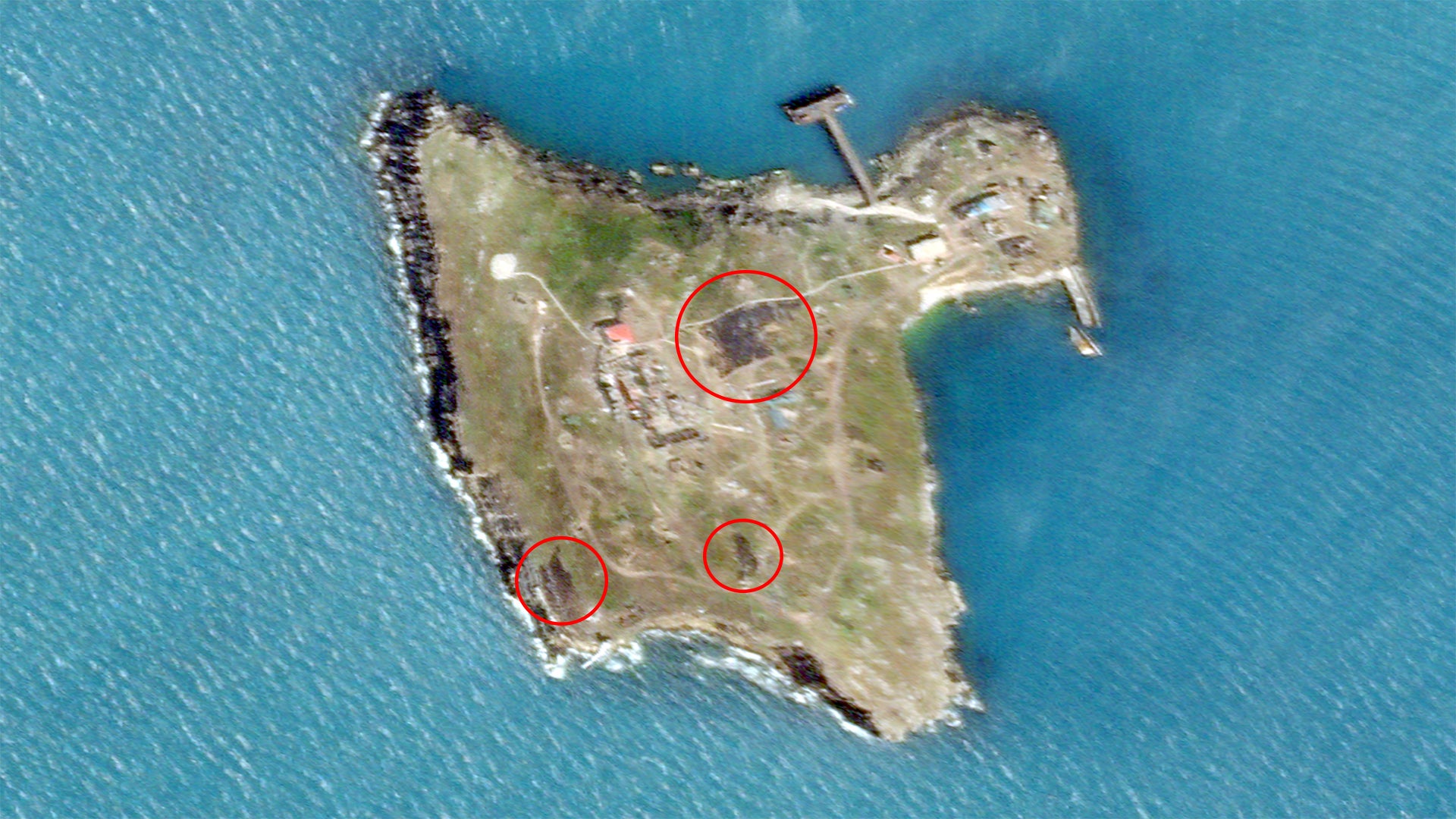

Ukrainian Strikes On Russian-Occupied Snake Island Confirmed In Satellite Imagery

Ukraine says a new operation is underway targeting Russian forces on Snake Island in the Black Sea.

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Well shyt they basically told all men from 18 to 60 to sgay and fight right?zelensky admitted that they are outnumbered in the donbas region, more weapons is good, but they need to basically double the size of their army to kick the russians out as opposed to just playing defense

I know Ukraine has second largest army in Europe

Forreal Somalia gets all their grain from Ukraine/Russia and Egpyt over 80%.Can't believe this shyt is ongoing. Russia gotta wake the fukk up.

Africa is hurting already ..and it's made worst by Putin chump ass.

I don't think this ends until Russia has a firm grip.on Ukraine ports and blocking Ukraine from the Black Sea.

Really?this is why the EU is feelin gully right now, russia without nukes is practically food to major armies around the world.

I read otherwise

Germany is being hesitant on giving support to Ukraine. EU isn't as cohesive as once stated.

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

Virtuous_Brotha

Superstar

Why the fuk is this still going on  i'm sick of my portfolio shyting itself and i'm pretty sure this is the main culprit

i'm sick of my portfolio shyting itself and i'm pretty sure this is the main culprit

i'm sick of my portfolio shyting itself and i'm pretty sure this is the main culprit

i'm sick of my portfolio shyting itself and i'm pretty sure this is the main culpritOfTheCross

Veteran

the war is over. Ukraine lost. explained in the first 3 minutes here...

OfTheCross

Veteran

Mister Terrific

It’s in the name

35 years ago, Helmut Schmidt gave this ruthless assessment of Russia's politics - it reads more relevant today than ever

Romanus Otte1. May 2022

Former Federal Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (SPD) in 2005

With regard to Russia, Germany is struggling with its youngest former chancellors. Angela Merkel (CDU) is silent about the Ukraine war. Her predecessor Gerhard Schröder (SPD) stands undauntedly for Vladimir Putin. The SPD also finds it difficult to find its position on Russia anew. It could not only help her to turn back the view of a generation of chancellors: Helmut Schmidt - Chancellor from 1974 to 1982 - had a clear attitude and assessment. He considered Russia to be a missionary, aggressively expansionary power.

In his memoirs, which appeared from 1987 under the title "People and Powers", Schmidt dedicated the first chapter to Russia: "Living with the Russians." Schmidt sees the then still existing Soviet Union in the tradition of the Tsardom. His outlook on the looming change under Mikhail Gorbachev is skeptical. The "political-cultural tradition" of Russia, which is designed for expansion, is too deep. Schmidt gives many reasons for this. Putin agrees with him in many ways today.

Schmidt's analysis, who died in 2015 as a globally esteemed Elder Statesmen, reads more topical than ever. Here are Schmidt's most important theses and conclusions.

1. Russian Messianism

It is one of Russia's contradictions that traditions play an enormous role in politics in the country whose history is marked by breaks. Putin owes his rise to the disintegration of the Soviet Union, which in turn was caused by revolution. But Putin continues unwaveringly with both Tsarist and Stalinist traditions and seeks to join forces with the Russian Orthodox Church.Helmut Schmidt described these continuities before Putin's era as follows: "Lenin - and also Stalin - probably rightly regarded Ivan IV, "the Terrible", as the actual founder of the absolutist-centralist-centralist governed Greater Russian state." With Ivan's conquests, "the history of the expansion of the empire began, which brought about a far-reaching Russification of foreign peoples."

Whether under Ivan IV, Peter I or Catherine II, under Stalin, Khrushchev or Brezhnev: Despite some setbacks, the Russian urge for expansion has never really died out. It is based on a Moscow-centric Messianism, which has remained inherent in the Russian state idea. When Constantinople was conquered by the Turks in 1453 and the Eastern Roman center of Christianity was lost, Moscow declared itself the "Third Rome" (...) and there will be no fourth Rome. The certainty of salvation appeared in a different form in the second half of the 19th century. century as Moscowcentric Panslavism and again in the 20th century. Century as a world revolutionary Moscow-centric communism."

2. Unabled liberal democrats

Russians have hardly ever lived in a real democracy, at least not long enough for liberal-democratic traditions to have formed. Liberals are repeatedly inferior to National Russian Messianism.Schmidt: "All Russians who, in view of this question, have opted for the freedom of the person and the inviolability of their dignity, for the rule of law and for the open society, who reject the subordination of the individual to a collective will and value his fundamental rights higher than the claim of the state or its rulers - all these Russians have always been a minority - a politically mostly meaningless marginal group. It seems to me questionable whether this can change significantly under Gorbachev - as much as I hope so."

3. Error of the West: Moral illusion instead of firm attitude

Schmidt already sees it as a mistake in his time to convince Russian politicians of a moral superiority of Western models. "It makes little sense to repeatedly measure the politics of the Russians (...) with today's French, English or American standards; we will hardly influence them with it. They will be influenced even less with moral accusations and accusations; on the contrary, this can lead to a fierce retreat to Russian Messianism in Moscow."A real change would take at least generations. The SPD politician advises an illusionless, pragmatic, but firm policy: "In the meantime, it is necessary for the West to protect itself from the further expansion of Russian-Soviet power. Schmidt recalls US foreign politician Geroge F. Kennan, who described this in 1947 as follows: "The main element of any American policy towards the Soviet Union must be a long-term, patient, but at the same time firm and growing containment of expansionary Russian aspirations."

4. Russia's security complex

Schmidt had himself participated in the German war of aggression against the Soviet Union as an officer of the Wehrmacht during World War II, including the siege of the then Leningrad (today again St. Petersburg). Schmidt exchanged several times with Leonid Brezhnev, almost Soviet head of state, about the war at the end of the 1970s. Brezhnev knew about the enormous victims of the former Soviet Union. But he also realized that mistrust went beyond that.Schmidt: "The leaders of the Soviet Union suffer from a Russian security complex, which first became noticeable after the defeat in 1856." He summarizes this attitude with the quote of an unnamed minister from the Tsarist era: "The border of Russia is only safe if Russian soldiers are on both sides." Stalin also created a "wree of upstream satellite states" for this reason. The USA would have responded with its alliances in Europe, Asia and the Middle East. This, in turn, had been perceived by Moscow as a threatening encirclement.

Today, this seems to be reflected in Putin's claim that NATO is encircling Russia. A look at the map exposes this as a complex.

5. Russia's inferiority complex

In the competition of ideologies after the Second World War, something else was added, Schmidt writes: "The pursuit of an equal global strategic rank and 'same security' as the other world power was not only defense policy nature. It was also compensation for the inferiority complex of the Soviet Union in view of its inability to economically catch up with Western industrial societies."6. A skeptical outlook

Recognizing the extensive continuity of Russian expansion in history does not mean believing in geopolitical determination, writes Schmidt. It seems to be more of a political-cultural tradition that has never given up the sense of mission, which originally emanated from the Russian Orthodox Church, later received and continued by the CPSU. Looking ahead, Schmidt writes: "It is not clear whether there can be a significant, lasting change of this old tradition under Gorbachev."Schmidt had no idea about Putin at that time. Nevertheless, he suspected the historical continuities that would determine Putin's thinking and Russia's actions.

"The border of Russia is only safe if Russian soldiers are on both sides."

That sums them up.

That sums them up.

PewPew

I came from nothing

I told you so. But like fools you clung to what MSM and Malcom Nance told you.

I told yall there were mass surrenders and defections in Ukraine's . I told yall the artillery was chewing up Ukraine. Even Zelensky is admitting to losing 100 to 200 soldiers PER DAY. And that's just KIA, not including WIA or MIA.

The Russians just closed another major pocket today and trapped up to 3K soldiers of Ukraine. Theyre going to keep taking land until Ukraine is completely landlocked.

The Lithuania play by NATO was brilliant though, i wonder how Russia will counter that

I told yall there were mass surrenders and defections in Ukraine's . I told yall the artillery was chewing up Ukraine. Even Zelensky is admitting to losing 100 to 200 soldiers PER DAY. And that's just KIA, not including WIA or MIA.

The Russians just closed another major pocket today and trapped up to 3K soldiers of Ukraine. Theyre going to keep taking land until Ukraine is completely landlocked.

The Lithuania play by NATO was brilliant though, i wonder how Russia will counter that

Ukrainian lines are collapsingI told you so. But like fools you clung to what MSM and Malcom Nance told you.

I told yall there were mass surrenders and defections in Ukraine's . I told yall the artillery was chewing up Ukraine. Even Zelensky is admitting to losing 100 to 200 soldiers PER DAY. And that's just KIA, not including WIA or MIA.

The Russians just closed another major pocket today and trapped up to 3K soldiers of Ukraine. Theyre going to keep taking land until Ukraine is completely landlocked.

The Lithuania play by NATO was brilliant though, i wonder how Russia will counter that