BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY MACDUFF EVERTON / CORBIS

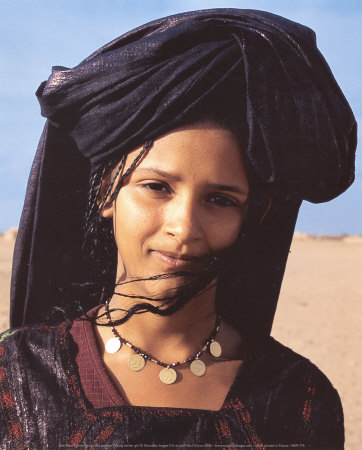

“History changes things,” says author Cornelia Walker Bailey, (

above) who lives on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Her surname started out as Bilali, the given name of her ancestor Bilali Mohammed. Trained as a Muslim prayer leader in his native Guinea, he was enslaved in 1803 and brought to Sapelo Island, where a small community of his descendants still lives. Bailey grew up saying Christian prayers facing east, the direction of Makkah—the same direction in which her Muslim ancestor prayed.

Above Left : W. C. Handy, “Father of the Blues” and a son of former slaves, recorded a 1903 encounter with a man playing an instrument that was evolving from an African zither into an American slide guitar.

Written by Jonathan Curiel

ylviane Diouf knows her audience might be skeptical, so to demonstrate the connec- tion between Muslim traditions and American blues music, she’ll play two recordings: The

athaan, the Muslim call to prayer that’s heard from minarets around the world, and “Levee Camp Holler,” an early type of blues song that first sprang up in the Mississippi Delta more than 100 years ago.

“Levee Camp Holler” is no ordinary song. It’s the product of ex-slaves who worked moving earth all day in post-Civil War America. The version that Diouf uses in presentations has lyrics that, like the call to prayer, speak about a glorious God. But it’s the song’s melody and note changes that closely resemble oneof Islam’s best-known refrains. Like the call to prayer, “Levee Camp Holler” emphasizes words that seem to quiver and shake in the reciter’s vocal chords. Dramatic changes in musical scales punctuate both “Levee Camp Holler” and the adhan. A nasal intonation is evident in both.

ALAN LOMAX COLLECTION / SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION / "PRISON SONGS", VOL. 1, TRACK 11, ROUNDER RECORDS

“I did a talk a few years ago at Harvard where I played those two things, and the room absolutely exploded in clapping, because [the connection] was obvious,” says Diouf, an author and scholar who is also a researcher at New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. “People were saying, ‘Wow. That’s really audible. It’s really there.’” It’s really there thanks to all the Muslim slaves from West Africa who were taken by force to the United States for three centuries, from the 1600’s to the mid-1800’s. Upward of 30 percent of the African slaves in the United States were Muslim, and an untold number of them spoke and wrote Arabic, historians say now. Despite being pressured by slave owners to adopt Christianity and give up their old ways, many of these slaves continued to practice their religion and customs, or otherwise melded traditions from Africa into their new environment in the antebellum South. Forced to do menial, backbreaking work on plantations, for example, they still managed, throughout their days, to voice a belief in God and the revelation of the Qur’an. These slaves’ practices eventually evolved—decades and decades later, parallel with different singing traditions from Africa—into the shouts and hollers that begat blues music, Diouf and other historians believe.

JOHN GABRIEL STEDMAN, NARRATIVE… (LONDON, 1796) / THE MARINER’S MUSEUM

African Muslim slaves influenced later blues both through their musical style and through their instruments, which, in late-18th-century Suriname, included percussion, wind and string devices. Among the latter were a one-string benta (top left), and a Creole-bania (top right), an ancestor of the American banjo.

Another way that Muslim slaves had an indirect influence on blues music is the instruments they played. Drumming, which was common among slaves from the Congo and other non-Muslim regions of Africa, was banned by white slave owners, who felt threatened by its ability to let slaves communicate with each other and by the way it inspired large gatherings of slaves.

Stringed instruments, however—favored by slaves from Muslim regions of Africa, where there’s a long tradition of musical storytelling—were generally allowed because slave owners considered them akin to European instruments such as the violin. So slaves who managed to cobble togethera banjo or other instrument—the American banjo originated with African slaves—could play more widely in public. This solo-oriented slave music featured elements of an Arabic–Muslim song style that had been imprinted by centuries of Islam’s presence in West Africa, says Gerhard Kubik, a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of Mainz in Germany. Kubik has written the most comprehensive book on Africa’s connection to blues music,

Africa and the Blues (1999, University Press of Mississippi).

Kubik believes that many of today’s blues singers unconsciously echo these Arabic–Muslim patterns in their music. Using academic language to describe this habit, Kubik writes in

Africa and the Blues that “the vocal style of many blues singers using melisma, wavy intonation, and so forth is a heritage of that large region of West Africa that had been in contact with the Arabic–Islamic world of the Maghreb since the seventh and eighth centuries.” (Melisma is the use of many notes in one syllable; wavy intonation refers to a series of notes that veer from major to minor scale and back again, something that’s common in both blues music and in the Muslim call to prayer as well as recitation of the Qur’an. The Maghreb is the Arab–Muslim region of North Africa.)

Kubik summarizes his thesis this way: “Many traits that have been considered unusual, strange and difficult to interpret by earlier blues researchers can now be better understood as a thoroughly processed and transformed Arabic–Islamic stylistic component.”

The extent of this link between Muslim culture and American blues music is still being debated. Some scholars insist there is no connection, and many of today’s best-known blues musicians would say their music has little to do with Muslim culture. Yet a growing body of evidence—gathered by academics such as Kubik and by others such as Cornelia Walker Bailey, a Georgia author whose great-great-great-great-grandfather was a slave who prayed toward Makkah—suggests a deep relationship between slaves of Islamic descent and us culture. While Muslim slaves from West Africa were just one factor in the formation of American blues music, they

were a factor, says Barry Danielian, a trumpeter who’s performed with Paul Simon, Natalie Cole and Tower of Power.

Bailey, who visited West Africa in 1989, says the African and Muslim roots of southern us traditionsare often mistaken for something else.

Bailey lives on Georgia’s Sapelo Island, where some blacks can trace their ancestry to Bilali Mohammed, a Muslim slave who was born and raised in what is now the African nation of Guinea. Visitors to Sapelo Island are always struck by the fact that churches there face east. In fact, as a child, Bailey learned to say her prayers facing east—the same direction that her great-great-great-great-grandfather faced when he prayed toward Makkah.

Bilali was an educated man. He spoke and wrote Arabic, carried a Qur’an and a prayer rug, and wore a fez that likely signified his religious devotion. Bilali had been trained in Africa to be a Muslim leader; on Sapelo Island, he was appointed by his slave master to be an overseer of other slaves. Although Bilali’s descendents adopted Christianity, they incorporated Muslim traditions that are still evident today.

COURTESY BARRY DANIELIAN / BDEEP MUSIC

To trumpeter Barry Danielian, Muslim prayers are “very musical. You hear what we as Americans would call soulfulness or blues. That’s definitely in there.”

The name Bailey, in fact, is a reworking of the name Bilali, which became a popular Muslim name in Africa because one of Islam’s first converts—and the religion’s first muezzin—was a former Abyssinian slave named Bilal. (Muezzins are those who call Muslims to prayer.) One historian believes that abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who changed his name from Frederick Bailey, may also have had Muslim roots.

“History changes things,” says Bailey, who chronicled the history of Sapelo Island in her memoir

God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man (2001, Anchor). “Things become something different from what they started out as.”

Cornelia Bailey and Mother

Cornelia Bailey and Mother Cornelia Bailey with Jimmy Carter

Cornelia Bailey with Jimmy Carter Sapelo Island Cultural Day

Sapelo Island Cultural Day

I feel like they let the cac perspectives dictate there conclusions.

I feel like they let the cac perspectives dictate there conclusions.

I want to say Nigeria is an intermediate but isn't the ancestral proto-Bantu homeland in West Africa near the present-day Nigeria and Cameroon? How does the SE bantu DNA look compared with an Nigerian?

I want to say Nigeria is an intermediate but isn't the ancestral proto-Bantu homeland in West Africa near the present-day Nigeria and Cameroon? How does the SE bantu DNA look compared with an Nigerian?