In the winter of 2011-2012,

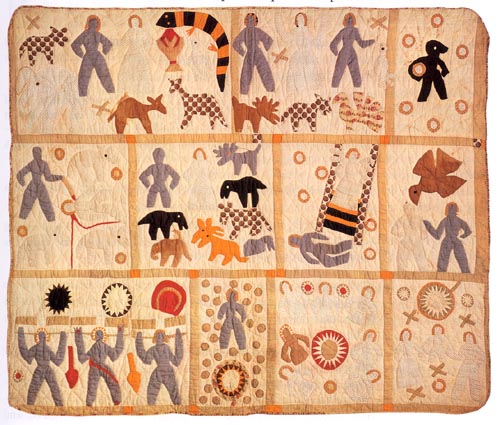

Mark Newell and April Hynes, archaeologists working on the remains of a pottery works at Edgefield, South Carolina unearthed substantial remains of a pottery tradition started by local potters of African origin, working as slaves. The archaeologists extended their project to include an interesting history of some of the potters, who could be identified through records as survivors from one of the last ships to make slave trading visits to the African ports and left their unwilling cargo in Charleston. These enslaved potters ultimately hailed from the region around the mouth of the Congo River in West Central Africa, and contemporary biographies occasionally mentioned rivers and villages that were probably located in the Kingdom of Kongo.

This Kongo to South Carolina connection was an old one, in the eighteenth century the founding generation of Afro-South Carolinians came frequently from the West Central African region, in fact the largest single group before 1740, and over half the imports in what was at the time the most Africanized region of English North America. The slave trade, which continued in the region right into the early nineteenth century was frequently dominated by West Central Africans and so that region and its culture is foundational to much of South Carolina’s African population, and through them to much of the cultural and biological heritage of African Americans elsewhere as well.

In light of these discoveries, the African American Studies program is holding a workshop on September 27, 2012 to discuss the connection between Kongo and North America and Kongo’s role in shaping American culture.

Boston University’s African American Studies program is uniquely situated to undertake this workshop as two of our faculty (Linda Heywood and John Thornton) are internationally known experts on Kongo and West Central Africa, and Boston University has a long standing and excellent African Studies Program.

In addition to the two archaeologists, and two Boston University faculty, the workshop includes art historian Cécile Fromont, Professor of University of Chicago, whose work has been devoted to the Kingdom of Kongo’s Christian art.