cole phelps

Superstar

Riot

Altercations between black and white youths started on June 20, 1943, on a warm Saturday evening on Belle Isle. A fist fight broke out when a white sailor's girlfriend was insulted by a black man. The brawl eventually grew into a confrontation between groups of blacks and whites and then spread into the city. The riot escalated with a rumor that a mob of whites had thrown an African-American mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Historian Marilynn S. Johnson argues that this rumor reflected black male outrage over white violence against black women and children.[10][11] Another false rumor swept white neighborhoods that blacks had raped and murdered a white woman on the Belle Isle Bridge. Angry mobs of whites spilled onto Woodward near the Roxy Theater around 4 a.m., beating blacks as they were getting off street cars.[12] Stores were looted and buildings were burned in the riot, most of them in a black neighborhood in and around Paradise Valley, Detroit, one of the oldest and poorest neighborhoods in Detroit. The clashes soon escalated to the point where black and white mobs were “assaulting one another, beating innocent motorists, pedestrians and streetcar passengers, burning cars, destroying storefronts and looting businesses."[3] Both sides were said to have encouraged others to join in the riots with false claims that one of "their own" was attacked unjustly.[3]

Aftermath

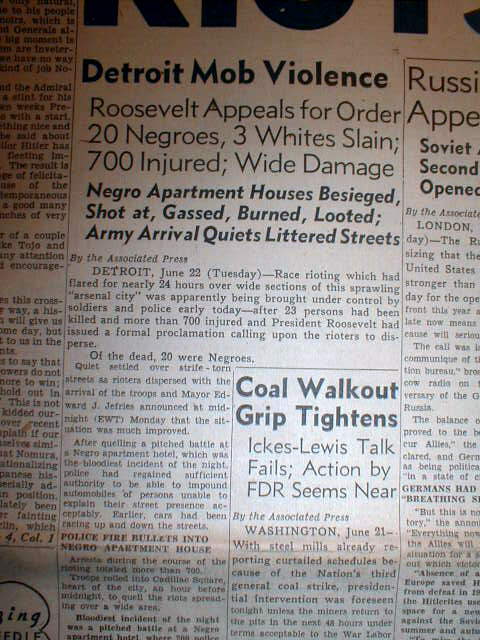

The riots lasted three days and ended once Mayor Jeffries and Governor Harry Kelly asked President Roosevelt to intervene. Federal troops finally restored peace to the streets of Detroit. Over the course of three days, 34 people were killed. Of them, 25 were African–Americans, 17 of whom were killed by the police. Thirteen murders remain unsolved. Out of the approximately 600 injured, black people accounted for more than 75 percent and of the roughly 1,800 people who were arrested over the course of the three-day riots, black people accounted for 85 percent.[3]

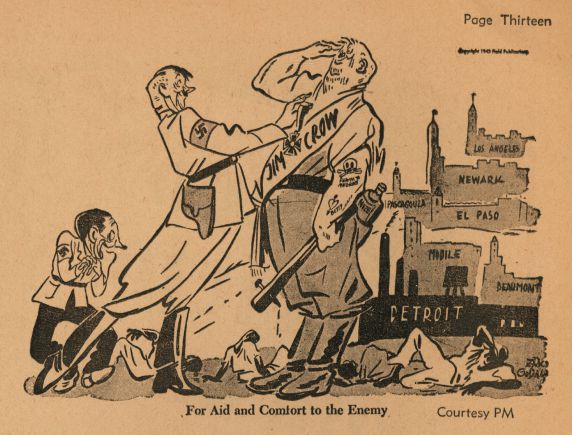

After the riot, leaders on both sides had an explanation for the riots. White city leaders including the mayor blamed young black “hoodlums”.[3] The Wayne County prosecutor believed that the leaders of the NAACP were to blame as the instigators of the riots.[3] Detroit's black leaders pointed to other causes ranging from job discrimination, to housing discrimination, police brutality, and daily animosity received from Detroit's white population.[3] Following the violence, Japanese propaganda officials incorporated the event into its materials encouraging black soldiers not to fight for the United States, most notably in a flyer titled "Fight Between Two Races".[13]

According to The Detroit News:

Future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, then with the NAACP, assailed the city's handling of the riot. He charged that police unfairly targeted blacks while turning their backs on white atrocities. He said 85 percent of those arrested were black while whites overturned and burned cars in front of the Roxy Theater with impunity while police watched. "This weak-kneed policy of the police commissioner coupled with the anti-Negro attitude of many members of the force helped to make a riot inevitable."[14]

Altercations between black and white youths started on June 20, 1943, on a warm Saturday evening on Belle Isle. A fist fight broke out when a white sailor's girlfriend was insulted by a black man. The brawl eventually grew into a confrontation between groups of blacks and whites and then spread into the city. The riot escalated with a rumor that a mob of whites had thrown an African-American mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Historian Marilynn S. Johnson argues that this rumor reflected black male outrage over white violence against black women and children.[10][11] Another false rumor swept white neighborhoods that blacks had raped and murdered a white woman on the Belle Isle Bridge. Angry mobs of whites spilled onto Woodward near the Roxy Theater around 4 a.m., beating blacks as they were getting off street cars.[12] Stores were looted and buildings were burned in the riot, most of them in a black neighborhood in and around Paradise Valley, Detroit, one of the oldest and poorest neighborhoods in Detroit. The clashes soon escalated to the point where black and white mobs were “assaulting one another, beating innocent motorists, pedestrians and streetcar passengers, burning cars, destroying storefronts and looting businesses."[3] Both sides were said to have encouraged others to join in the riots with false claims that one of "their own" was attacked unjustly.[3]

Aftermath

The riots lasted three days and ended once Mayor Jeffries and Governor Harry Kelly asked President Roosevelt to intervene. Federal troops finally restored peace to the streets of Detroit. Over the course of three days, 34 people were killed. Of them, 25 were African–Americans, 17 of whom were killed by the police. Thirteen murders remain unsolved. Out of the approximately 600 injured, black people accounted for more than 75 percent and of the roughly 1,800 people who were arrested over the course of the three-day riots, black people accounted for 85 percent.[3]

After the riot, leaders on both sides had an explanation for the riots. White city leaders including the mayor blamed young black “hoodlums”.[3] The Wayne County prosecutor believed that the leaders of the NAACP were to blame as the instigators of the riots.[3] Detroit's black leaders pointed to other causes ranging from job discrimination, to housing discrimination, police brutality, and daily animosity received from Detroit's white population.[3] Following the violence, Japanese propaganda officials incorporated the event into its materials encouraging black soldiers not to fight for the United States, most notably in a flyer titled "Fight Between Two Races".[13]

According to The Detroit News:

Future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, then with the NAACP, assailed the city's handling of the riot. He charged that police unfairly targeted blacks while turning their backs on white atrocities. He said 85 percent of those arrested were black while whites overturned and burned cars in front of the Roxy Theater with impunity while police watched. "This weak-kneed policy of the police commissioner coupled with the anti-Negro attitude of many members of the force helped to make a riot inevitable."[14]