You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Putin’s Attack on Ukraine Is a Religious War. Incredible insight to the schism of Russian orthodoxy

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?tabletmag.com

A Church Divided

Maggie Phillips

12-15 minutes

Although Ukraine and Russia share deep Orthodox Christian roots, fissures have emerged between the two countries’ branches of the Orthodox Church, with implications for Orthodox churches here in the United States. The effects are especially noticeable in Pittsburgh, home to a large Orthodox Christian population. The crisis comes amid an appreciable increase of converts in the U.S., creating complex problems for both clergy and laity.

Current discourse about staving off a Russian invasion of Ukraine is mostly centered around natural gas and money—and whether stanching the flow of either will be sufficient to deter Vladimir Putin’s revanchist ambitions. However, it is the flow of the Dnieper River that directs the student of history to the ancient origins of this conflict. It was in the current of these waters that another Vladimir had his people baptized over a millennium ago, and the effects of that decision have continued to extend through the centuries to the present day.

Recognized as a saint in the Orthodox faith, Vladimir—or Volodymyr, in Ukrainian—was a prince of the Eastern Slavic peoples, who was baptized in 988 CE in what is now Crimea. It was the seminal founding of Orthodoxy in what was then called Kievan Rus, often evoked as the cultural and historical place of origin of the Russian people. “In those days, the people took the same religion as their prince, so Vladimir had his people baptized en masse,” said John Burgess, a professor at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary who specializes in post-Soviet Orthodox Christianity, and who has been studying the area for almost two decades. “He had most of his warriors and people baptized in the Dnieper River that flows through Kyiv.”

Both Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox Christians view this event as their spiritual origin. “You have sort of dueling histories,” Burgess said. “You have Moscow who says we’re the legitimate heirs of 988, we’re the ones who maintain that tradition through the centuries, and now you have the Kievan Orthodox in Ukraine say no, actually we’re the legitimate heirs.”

As is often the case with Ukrainian and Russian relations, the relationship between the two churches is complicated. For one thing, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church dates back only to 2019, the culmination of decades of a cultural identity crisis in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is also one of two Orthodox churches in Ukraine.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukrainian independence in 1991, a split emerged. Some Ukrainian Orthodox leaders wanted to be independent, while others wanted to remain loyal to Moscow. In 2019, the faction favoring independence received permission from the Patriarch of Constantinople to form the Ukrainian Orthodox Church with its head (called a metropolitan) in Kyiv. While the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is autonomous, the imprimatur of the Patriarch of Constantinople confers legitimacy upon it, since the Patriarch’s authority traces its own origins back to the Emperor Constantine, and the establishment of a Christian capital in Byzantium in the fourth century.

Once it broke away, the independent Ukrainian church united existing Ukrainian Orthodox churches in the country to form one unified national Ukrainian Orthodox Church under a single metropolitan. The result is that Ukraine now hosts two rival Orthodox churches: one oriented toward Moscow, and another toward Constantinople.

The Patriarchate’s decision to back the creation of a Ukrainian Orthodox Church was the catalyst for a formal split, wherein the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow broke Eucharistic communion with Constantinople. As the word “communion” suggests, this is a fracturing wherein adherents of the Russian Orthodox Church may not partake, at Ukrainian Orthodox churches, in the bread and wine that are believed to be the genuine body and blood of Christ, a practice meant to unify believers with God and with each other. Likewise, neither may members of the new Ukrainian Orthodox Church partake at Russian churches.

The current intermingling of nationalism and religion overseas has practical effects for American Orthodox Christians. This is especially true in Pittsburgh, which has multiple Orthodox churches falling under various jurisdictions with ties to different countries of origin.

While the Orthodox presence in the U.S. dates back to the 18th century with Russian missionaries in Alaska, its presence in Pittsburgh begins with immigrants to the city from Eastern Europe and the Middle East, arriving in the 19th and early 20th centuries seeking steel jobs. While they would build ethnic churches as their respective communities took hold in their new country, they built them close to each other out of a sense of spiritual kinship, and they all recognized the authority of the Orthodox Church in Moscow. Ties to ethnic churches and national jurisdictions in their countries of origin became more important after 1917 and the weakening of the Orthodox Church in Russia under the Bolsheviks.

Russian Orthodox Church, Pittsburgh, 1938Library of Congress

“The irony is that the consequences [of the schism between Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox churches] in the United States are much greater than they are in Moscow,” said Father Thomas Soroka, an Orthodox Priest in Pittsburgh, “because we have these parallel jurisdictions.” He describes attending a meeting of Greek, Ukrainian, Antiochian, and Serbian Orthodox clergy in Pittsburgh. “In America, unlike in Russia, unlike in Turkey, unlike in Greece, our friends, our relatives go to the Russian church or the Greek church or the Serbian church or the Antiochian church or the OCA [Orthodox Church in America] church. When there is a schism like this, it causes tremendous practical difficulties for us in America.” Whereas in Russia, he said, while “it’s a very serious matter to break communion with another church, there are no practical consequences ultimately, because there are no Greek churches in Russia.”

“Here in America, there are Greek Orthodox churches just down the road from a Russian Orthodox church, which is just down the road from a Serbian church, which is just down the road from a Ukrainian church,” said Soroka. “So all of a sudden, we priests find ourselves not being able necessarily to commune with one another and serve with one another.”

Soroka identifies two practical effects: scandalizing converts and complicating pastoral relations between clergy.

While Orthodoxy in the U.S. is declining as a whole, as older members pass away and younger immigrant members disaffiliate, various Orthodox jurisdictions are enjoying an influx of members. In a shift Soroka called “almost unprecedented,” he said, “We have churches that have 40, 50, 60 people that are entering the faith.” The uptick is “really quite remarkable,” Soroka said, appreciable because “these aren’t churches of two, three thousand people. These are churches of 150, 200 people that have 60 people in the wings, waiting to come in.”

According to Sarah Riccardi-Swartz, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University who specializes in the Russian Orthodox Church outside of Russia, many American converts are former evangelicals and others from largely Protestant Christian denominations who are drawn to the history, tradition, and what they view as the authenticity of the faith. “For them,” she said, “it’s a community that could withstand, at least in the diaspora, socialism, and somehow come back in the post-Soviet period. At least that’s what they see in Russia right now, they see a revival of Orthodoxy, from their viewpoint.” Despite being “dormant for a good part of the 20th century in Russia,” said Riccardi-Swartz, “it still had that flame and was able to return somewhat emboldened.” Soroka says the reasons for the rise in converts are complicated, but he points to COVID-19 as one of them. He also says part of Orthodoxy’s appeal to converts comes from the sense of retreat it gives them from a society adrift in ideological confusion, creating a “haven” of moral clarity through its more traditional values. “We’re not here to simply be a temporary holding space,” he said.

Riccardi-Swartz describes the typical convert to Orthodoxy as a white male anywhere between 20 and 60 years of age, often with a B.A. or an M.A., “very well-read, very intelligent, and articulate.” They are often predisposed to learn about subjects like philosophy and theology, and come to the faith by reading about church history, either through either autodidactic or institutional learning. “And,” she said, “through finding each other online.”

It’s the online interaction that poses a problem from Soroka’s point of view, as he sees internet discussions between converts about the current Ukrainian-Russian split becoming yet another form of online tribal politics. “It’s kind of like a family airing their dirty laundry,” he said. “It’s extremely uncomfortable, and it’s extremely disheartening, and it also can be a little bit, I think, confusing for converts. They don’t necessarily understand that this is a family matter, that this is a temporary matter. If church history proves anything, this is not going to be long-lived. It will be resolved.”

Soroka said that while converts may home in on intra-Orthodox divisions and feel compelled to pick a side, this online tribalism can exacerbate division: “It actually becomes worse.” Riccardi-Swartz’s work takes place with more far-right Orthodox converts across various jurisdictions, although still broadly within the Russian Orthodox tradition. “They are really adamant online that Russia is in the right,” she said. “And that the autocephaly granted to Ukraine by the Ecumenical Patriarch was a massive theological error, and that the potential for Russian invasion of Ukraine right now is spurred on by the secular U.S. government that sees Russia as a threat, because Russia is trying to revitalize traditional social values and Christianity.”

When it comes to the day-to-day impacts of the split between Moscow and the Patriarchate in Constantinople over the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Soroka says he thinks that on the pastoral level “priests have been very good about saying look, we’re all Orthodox and you should come to our church.” While he doesn’t think most priests are making a distinction, “I do think that it becomes difficult, because in the United States what we call here in Pittsburgh the Orthodox Clergy Brotherhood, which simply means once a year or twice a year, we all get together and serve services together. Now it’s like, well, this bishop is really not in communion with that bishop, and this priest is not really in communion with that priest, can they serve together, and can they have [communion] together?”

Contra Marx, at least with regard to Ukraine and Russia, religion is far from an opiate. It is a stimulant, with religious politics clearly tied to international politics. Prior to the creation of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Ukrainian police raided the buildings and homes of priests affiliated with Orthodox churches favoring Moscow, to search for evidence of inciting hatred and violence. And it was former Ukrainian Petro Poroshenko who hosted the 2018 stakeholders’ meeting of Ukrainian Orthodox religious leaders around the same time, to discuss breaking away from Moscow. Poroshenko called the 2019 inauguration of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church a historic moment, when Ukraine “finally received its independence from Russia.”

Current Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky struck a more conciliatory tone shortly after the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s institution, urging unity. More recently, given that Constantinople is now Istanbul, it is significant that Zelensky has signaled support for the Constantinople-backed church (and vice-versa), in light of Turkey’s support for Ukraine during its ongoing tensions with Russia. The U.S. State Department, in turn, publicly voiced support for the institution of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in 2018, and backs the Constantinople Patriarchate over the issue of religious freedom in Turkey.

Ultimately, Soroka worries about the effect of this muddying of statecraft and religion on the faithful. “It hurts our witness,” he said. “It becomes a reminder of our failure to really overcome these differences in a Christian manner.”

This story is part of a yearlong series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

A Church Divided

Maggie Phillips

12-15 minutes

Although Ukraine and Russia share deep Orthodox Christian roots, fissures have emerged between the two countries’ branches of the Orthodox Church, with implications for Orthodox churches here in the United States. The effects are especially noticeable in Pittsburgh, home to a large Orthodox Christian population. The crisis comes amid an appreciable increase of converts in the U.S., creating complex problems for both clergy and laity.

Current discourse about staving off a Russian invasion of Ukraine is mostly centered around natural gas and money—and whether stanching the flow of either will be sufficient to deter Vladimir Putin’s revanchist ambitions. However, it is the flow of the Dnieper River that directs the student of history to the ancient origins of this conflict. It was in the current of these waters that another Vladimir had his people baptized over a millennium ago, and the effects of that decision have continued to extend through the centuries to the present day.

Recognized as a saint in the Orthodox faith, Vladimir—or Volodymyr, in Ukrainian—was a prince of the Eastern Slavic peoples, who was baptized in 988 CE in what is now Crimea. It was the seminal founding of Orthodoxy in what was then called Kievan Rus, often evoked as the cultural and historical place of origin of the Russian people. “In those days, the people took the same religion as their prince, so Vladimir had his people baptized en masse,” said John Burgess, a professor at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary who specializes in post-Soviet Orthodox Christianity, and who has been studying the area for almost two decades. “He had most of his warriors and people baptized in the Dnieper River that flows through Kyiv.”

Both Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox Christians view this event as their spiritual origin. “You have sort of dueling histories,” Burgess said. “You have Moscow who says we’re the legitimate heirs of 988, we’re the ones who maintain that tradition through the centuries, and now you have the Kievan Orthodox in Ukraine say no, actually we’re the legitimate heirs.”

As is often the case with Ukrainian and Russian relations, the relationship between the two churches is complicated. For one thing, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church dates back only to 2019, the culmination of decades of a cultural identity crisis in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. It is also one of two Orthodox churches in Ukraine.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and Ukrainian independence in 1991, a split emerged. Some Ukrainian Orthodox leaders wanted to be independent, while others wanted to remain loyal to Moscow. In 2019, the faction favoring independence received permission from the Patriarch of Constantinople to form the Ukrainian Orthodox Church with its head (called a metropolitan) in Kyiv. While the Ukrainian Orthodox Church is autonomous, the imprimatur of the Patriarch of Constantinople confers legitimacy upon it, since the Patriarch’s authority traces its own origins back to the Emperor Constantine, and the establishment of a Christian capital in Byzantium in the fourth century.

Once it broke away, the independent Ukrainian church united existing Ukrainian Orthodox churches in the country to form one unified national Ukrainian Orthodox Church under a single metropolitan. The result is that Ukraine now hosts two rival Orthodox churches: one oriented toward Moscow, and another toward Constantinople.

The Patriarchate’s decision to back the creation of a Ukrainian Orthodox Church was the catalyst for a formal split, wherein the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow broke Eucharistic communion with Constantinople. As the word “communion” suggests, this is a fracturing wherein adherents of the Russian Orthodox Church may not partake, at Ukrainian Orthodox churches, in the bread and wine that are believed to be the genuine body and blood of Christ, a practice meant to unify believers with God and with each other. Likewise, neither may members of the new Ukrainian Orthodox Church partake at Russian churches.

The current intermingling of nationalism and religion overseas has practical effects for American Orthodox Christians. This is especially true in Pittsburgh, which has multiple Orthodox churches falling under various jurisdictions with ties to different countries of origin.

While the Orthodox presence in the U.S. dates back to the 18th century with Russian missionaries in Alaska, its presence in Pittsburgh begins with immigrants to the city from Eastern Europe and the Middle East, arriving in the 19th and early 20th centuries seeking steel jobs. While they would build ethnic churches as their respective communities took hold in their new country, they built them close to each other out of a sense of spiritual kinship, and they all recognized the authority of the Orthodox Church in Moscow. Ties to ethnic churches and national jurisdictions in their countries of origin became more important after 1917 and the weakening of the Orthodox Church in Russia under the Bolsheviks.

Russian Orthodox Church, Pittsburgh, 1938Library of Congress

“The irony is that the consequences [of the schism between Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox churches] in the United States are much greater than they are in Moscow,” said Father Thomas Soroka, an Orthodox Priest in Pittsburgh, “because we have these parallel jurisdictions.” He describes attending a meeting of Greek, Ukrainian, Antiochian, and Serbian Orthodox clergy in Pittsburgh. “In America, unlike in Russia, unlike in Turkey, unlike in Greece, our friends, our relatives go to the Russian church or the Greek church or the Serbian church or the Antiochian church or the OCA [Orthodox Church in America] church. When there is a schism like this, it causes tremendous practical difficulties for us in America.” Whereas in Russia, he said, while “it’s a very serious matter to break communion with another church, there are no practical consequences ultimately, because there are no Greek churches in Russia.”

“Here in America, there are Greek Orthodox churches just down the road from a Russian Orthodox church, which is just down the road from a Serbian church, which is just down the road from a Ukrainian church,” said Soroka. “So all of a sudden, we priests find ourselves not being able necessarily to commune with one another and serve with one another.”

Soroka identifies two practical effects: scandalizing converts and complicating pastoral relations between clergy.

While Orthodoxy in the U.S. is declining as a whole, as older members pass away and younger immigrant members disaffiliate, various Orthodox jurisdictions are enjoying an influx of members. In a shift Soroka called “almost unprecedented,” he said, “We have churches that have 40, 50, 60 people that are entering the faith.” The uptick is “really quite remarkable,” Soroka said, appreciable because “these aren’t churches of two, three thousand people. These are churches of 150, 200 people that have 60 people in the wings, waiting to come in.”

According to Sarah Riccardi-Swartz, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University who specializes in the Russian Orthodox Church outside of Russia, many American converts are former evangelicals and others from largely Protestant Christian denominations who are drawn to the history, tradition, and what they view as the authenticity of the faith. “For them,” she said, “it’s a community that could withstand, at least in the diaspora, socialism, and somehow come back in the post-Soviet period. At least that’s what they see in Russia right now, they see a revival of Orthodoxy, from their viewpoint.” Despite being “dormant for a good part of the 20th century in Russia,” said Riccardi-Swartz, “it still had that flame and was able to return somewhat emboldened.” Soroka says the reasons for the rise in converts are complicated, but he points to COVID-19 as one of them. He also says part of Orthodoxy’s appeal to converts comes from the sense of retreat it gives them from a society adrift in ideological confusion, creating a “haven” of moral clarity through its more traditional values. “We’re not here to simply be a temporary holding space,” he said.

Riccardi-Swartz describes the typical convert to Orthodoxy as a white male anywhere between 20 and 60 years of age, often with a B.A. or an M.A., “very well-read, very intelligent, and articulate.” They are often predisposed to learn about subjects like philosophy and theology, and come to the faith by reading about church history, either through either autodidactic or institutional learning. “And,” she said, “through finding each other online.”

It’s the online interaction that poses a problem from Soroka’s point of view, as he sees internet discussions between converts about the current Ukrainian-Russian split becoming yet another form of online tribal politics. “It’s kind of like a family airing their dirty laundry,” he said. “It’s extremely uncomfortable, and it’s extremely disheartening, and it also can be a little bit, I think, confusing for converts. They don’t necessarily understand that this is a family matter, that this is a temporary matter. If church history proves anything, this is not going to be long-lived. It will be resolved.”

Soroka said that while converts may home in on intra-Orthodox divisions and feel compelled to pick a side, this online tribalism can exacerbate division: “It actually becomes worse.” Riccardi-Swartz’s work takes place with more far-right Orthodox converts across various jurisdictions, although still broadly within the Russian Orthodox tradition. “They are really adamant online that Russia is in the right,” she said. “And that the autocephaly granted to Ukraine by the Ecumenical Patriarch was a massive theological error, and that the potential for Russian invasion of Ukraine right now is spurred on by the secular U.S. government that sees Russia as a threat, because Russia is trying to revitalize traditional social values and Christianity.”

When it comes to the day-to-day impacts of the split between Moscow and the Patriarchate in Constantinople over the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Soroka says he thinks that on the pastoral level “priests have been very good about saying look, we’re all Orthodox and you should come to our church.” While he doesn’t think most priests are making a distinction, “I do think that it becomes difficult, because in the United States what we call here in Pittsburgh the Orthodox Clergy Brotherhood, which simply means once a year or twice a year, we all get together and serve services together. Now it’s like, well, this bishop is really not in communion with that bishop, and this priest is not really in communion with that priest, can they serve together, and can they have [communion] together?”

Contra Marx, at least with regard to Ukraine and Russia, religion is far from an opiate. It is a stimulant, with religious politics clearly tied to international politics. Prior to the creation of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Ukrainian police raided the buildings and homes of priests affiliated with Orthodox churches favoring Moscow, to search for evidence of inciting hatred and violence. And it was former Ukrainian Petro Poroshenko who hosted the 2018 stakeholders’ meeting of Ukrainian Orthodox religious leaders around the same time, to discuss breaking away from Moscow. Poroshenko called the 2019 inauguration of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church a historic moment, when Ukraine “finally received its independence from Russia.”

Current Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky struck a more conciliatory tone shortly after the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s institution, urging unity. More recently, given that Constantinople is now Istanbul, it is significant that Zelensky has signaled support for the Constantinople-backed church (and vice-versa), in light of Turkey’s support for Ukraine during its ongoing tensions with Russia. The U.S. State Department, in turn, publicly voiced support for the institution of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in 2018, and backs the Constantinople Patriarchate over the issue of religious freedom in Turkey.

Ultimately, Soroka worries about the effect of this muddying of statecraft and religion on the faithful. “It hurts our witness,” he said. “It becomes a reminder of our failure to really overcome these differences in a Christian manner.”

This story is part of a yearlong series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

From 2014:

20committee.wordpress.com

Putin’s Orthodox Jihad

Posted by 20committee

20-26 minutes

Yesterday Russia announced a revised military doctrine, signed by President Vladimir Putin, that names NATO as the Kremlin’s main adversary and clarifies that Russia’s military reserves the right to respond to conventional threats with both nuclear and conventional weapons. This is no big change, since it only amplifies existing doctrine, but its explicit emphasis on NATO as the primary threat to Russia’s security has raised Western eyebrows, as intended. Anyone who thought the West, led by the United States, could lay waste to Russia’s economy through sanctions brought about by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, without significant pushback from Moscow, is too naive to deal in such important affairs. The new year promises to be a busy one, with myriad forms of retaliation emanating from Moscow, some possibly very unpleasant, as I recently explained.

My explanation back in March, on the heels of Russia’s theft of Crimea, that we are in Cold War 2.0, whether we like it or not, was dismissed as alarmist by those not well acquainted with Putin and his system, but has been borne out by events over the last nine months. One reason oft-cited by skeptics regarding the state of relations between Russia and the West is the supposed absence of an ideological component to the rivalry, which is a necessary precondition for any reborn Cold War. President Barack Obama has been one of the leading proponents of this hopeful view, stating: “This is not another Cold War that we’re entering into. After all, unlike the Soviet Union, Russia leads no bloc of nations. No global ideology. The United States and NATO do not seek any conflict with Russia.”

As I explained back in April, this view is wrong, and has only gotten wronger over the last several months. In fact, Putin should be seen as the leader of what I termed the Anti-WEIRD Coalition, the vanguard of the diverse movement that is opposed to Western post-modernism in its political and social forms — and particularly to its spread by governments, corporations, NGOs, or the bayonets of the U.S. military. While this should not be seen as any formal alliance, nor is it likely to become one, there exists an agglomeration of countries that are opposed to what the West, and especially America, represent on the world stage, and this was the year that Putin unambiguously took its helm.

What motivates this is a complex question. Putin is a complex character himself, with his worldview being profoundly shaped by his long service as a Soviet secret policeman; he exudes what Russians term Chekism — conspiracy-based thinking that sees plots abounding and is reflexively anti-Western, with heavy doses of machismo and KGB tough-talk. Hence persistent Western efforts to view Putin as any Western sort of democratic politician, albeit one with a strange affectation for judo and odd bare-chested photo-ops with scary wild animals, invariably miss the mark.

This year ending also saw the mask drop regarding Putin’s ideology beyond his bone-deep Chekism. In his fire-breathing speech to the Duma in March when he announced Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Putin included not just venerable KGB classics like warnings about the Western Fifth Column and “national traitors,” but also paeans to explicit Russian ethnic nationalism buttressed by Orthodox mysticism, with citations of saints from millennia past. This was the culmination of years of increasingly unsubtle hints from Putin and his inner circle that what ideologically motivates this Kremlin is the KGB cult unified with Russian Orthodoxy. Behind the Chekist sword and shield lurks the Third Rome, forming a potent and, to many Russians, plausible worldview. That this take on the planet and its politics is intensely anti-Western needs to be stated clearly.

But what of Putin’s actual beliefs? This knotty question is, strictly speaking, unanswerable, since only he knows his own soul. Putin’s powerful Chekism is beyond doubt, while many Westerners are skeptical that he is any sort of Orthodox believer. According to his own account, Putin’s father was a militant Communist while his mother was a faithful, if quiet, Orthodox believer; one wonders what holidays were like in the Putin household. He was baptized in secret as a child but was not any sort of engaged believer during his KGB service — that would have been impossible, not least due to the KGB’s role in persecuting religion — but by his own account, late in the Soviet period, Putin reconciled his Chekism with his faith by making the sign of the cross over his KGB credentials. By the late 1990’s, Putin was wearing his baptismal cross openly, for all bare-chested photo ops.

The turn to faith in middle-age, after some sort of life crisis, is a staple of conversion and reversion stories. In his last years in power, Saddam Hussein began talking a lot about Islam openly, which was dismissed as political theater in the West, but in retrospect seems to have been at least somewhat sincere. Did Putin opt for Orthodoxy after a mid-life crisis? I am an Orthodox believer myself and, having carefully watched many video clips of Putin in church and at religious events, I can state without reservation that Putin knows what to do. His religious act — kissing icons, lighting candles, interacting with clerics — is flawless, so Putin is either a sincere Orthodox or he has devoted serious study to looking and acting like one.

Whether this faith is genuine or a well-honed pose, Putin’s potent fusion of KGB values and Orthodoxy has been building for years, though few Westerners have noticed. Early in Putin’s years in the Kremlin, the younger generation of Federal Security Service (FSB) officers embraced a nascent ideology they termed “the system” (sistema), which was a sort of elitist Chekism — toughness free of corruption and based in patriotism — updated for the new 21st century. However, this could have limited appeal to the masses, so its place was gradually taken by a doctrine termed “spiritual security.” This involved the ideological fusion of the FSB and the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), culminating in the 2002 dedication of an Orthodox church at the Lubyanka, the FSB — and former KGB’s — notorious Moscow headquarters. It suddenly became fashionable for senior FSB officers to have conversion experiences, while “spiritual security” offered Putin’s Russia a way to defend itself against what it has long seen as the encroachment of decadent post-modern Western values. Just how seriously Putin took all this was his statement that Russia’s “spiritual shield” was as important to her security as her nuclear shield.

Nearly all Western experts, being mostly secularists when not atheists, paid no attention to these clear indications of where Putin was taking Russia, while the view of the few who did notice was colored by the perception that this simply had to be a put-up job by the Kremlin. But what if it is not? Skeptics are correct to note that Chekists have had a toxic and convoluted relationship with the ROC ever since Stalin, that failed Orthodox seminarian, resurrected the remnants of the Church, what little had survived vicious Bolshevik persecution, during the darkest days of the Great Patriotic War to buttress the regime with faith and patriotism — all tightly controlled by the secret police. There was the rub. Under the Soviets, all senior ROC appointments were subject to Chekist review, while nobody became a bishop without the KGB having some kompromat on him. This was understood by all, including the fact that a distressing number of ROC senior clerics were actual KGB agents. It’s not surprising that Putin omits from his CV that he worked for a time in the KGB’s Fifth Directorate, which supervised religious bodies, leading some to speculate that Putin’s relationship with certain ROC bishops extends deep into the late Soviet period.

The ROC is not Russia’s state religion, as Putin and top bishops have been at pains to state, but it cannot be denied that the Moscow Patriarchate’s close ties to the Kremlin grant it a very special relationship with Putinism. Whether this actually is symphonia, meaning the Byzantine-style unity of state and church which is something of an Orthodox ideal, in stark contrast to American notions of separation of church and state, remains to be seen, but Orthodoxy has become the close political and ideological partner of the Kremlin in recent years, a preferred vehicle for explicit anti-Western propaganda.

ROC agitprop, which has Kremlin endorsement, depicts a West that is declining down to its death at the hands of decadence and sin, mired in confused unbelief, bored and failing to even reproduce itself. Patriarch Kirill, head of the church, recently explained that the “main threat” to Russia is “the loss of faith” in the Western style, while ROC spokesmen constantly denounce feminism and the LGBT movement as Satanic creations of the West that aim to destroy faith, family, and nation. It is in this context that Putin’s comments at last year’s Valdai Club event ought to be seen:

Another serious challenge to Russia’s identity is linked to events taking place in the world. Here there are both foreign policy and moral aspects. We can see how many of the Euro-Atlantic countries are actually rejecting their roots, including the Christian values that constitute the basis of Western civilization. They are denying moral principles and all traditional identities: national, cultural, religious and even sexual. They are implementing policies that equate large families with same-sex partnerships, belief in God with the belief in Satan.

The excesses of political correctness have reached the point where people are seriously talking about registering political parties whose aim is to promote pedophilia. People in many European countries are embarrassed or afraid to talk about their religious affiliations. Holidays are abolished or even called something different; their essence is hidden away, as is their moral foundation. And people are aggressively trying to export this model all over the world. I am convinced that this opens a direct path to degradation and primitivism, resulting in a profound demographic and moral crisis.

20committee.wordpress.com

Putin’s Orthodox Jihad

Posted by 20committee

20-26 minutes

Yesterday Russia announced a revised military doctrine, signed by President Vladimir Putin, that names NATO as the Kremlin’s main adversary and clarifies that Russia’s military reserves the right to respond to conventional threats with both nuclear and conventional weapons. This is no big change, since it only amplifies existing doctrine, but its explicit emphasis on NATO as the primary threat to Russia’s security has raised Western eyebrows, as intended. Anyone who thought the West, led by the United States, could lay waste to Russia’s economy through sanctions brought about by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, without significant pushback from Moscow, is too naive to deal in such important affairs. The new year promises to be a busy one, with myriad forms of retaliation emanating from Moscow, some possibly very unpleasant, as I recently explained.

My explanation back in March, on the heels of Russia’s theft of Crimea, that we are in Cold War 2.0, whether we like it or not, was dismissed as alarmist by those not well acquainted with Putin and his system, but has been borne out by events over the last nine months. One reason oft-cited by skeptics regarding the state of relations between Russia and the West is the supposed absence of an ideological component to the rivalry, which is a necessary precondition for any reborn Cold War. President Barack Obama has been one of the leading proponents of this hopeful view, stating: “This is not another Cold War that we’re entering into. After all, unlike the Soviet Union, Russia leads no bloc of nations. No global ideology. The United States and NATO do not seek any conflict with Russia.”

As I explained back in April, this view is wrong, and has only gotten wronger over the last several months. In fact, Putin should be seen as the leader of what I termed the Anti-WEIRD Coalition, the vanguard of the diverse movement that is opposed to Western post-modernism in its political and social forms — and particularly to its spread by governments, corporations, NGOs, or the bayonets of the U.S. military. While this should not be seen as any formal alliance, nor is it likely to become one, there exists an agglomeration of countries that are opposed to what the West, and especially America, represent on the world stage, and this was the year that Putin unambiguously took its helm.

What motivates this is a complex question. Putin is a complex character himself, with his worldview being profoundly shaped by his long service as a Soviet secret policeman; he exudes what Russians term Chekism — conspiracy-based thinking that sees plots abounding and is reflexively anti-Western, with heavy doses of machismo and KGB tough-talk. Hence persistent Western efforts to view Putin as any Western sort of democratic politician, albeit one with a strange affectation for judo and odd bare-chested photo-ops with scary wild animals, invariably miss the mark.

This year ending also saw the mask drop regarding Putin’s ideology beyond his bone-deep Chekism. In his fire-breathing speech to the Duma in March when he announced Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Putin included not just venerable KGB classics like warnings about the Western Fifth Column and “national traitors,” but also paeans to explicit Russian ethnic nationalism buttressed by Orthodox mysticism, with citations of saints from millennia past. This was the culmination of years of increasingly unsubtle hints from Putin and his inner circle that what ideologically motivates this Kremlin is the KGB cult unified with Russian Orthodoxy. Behind the Chekist sword and shield lurks the Third Rome, forming a potent and, to many Russians, plausible worldview. That this take on the planet and its politics is intensely anti-Western needs to be stated clearly.

But what of Putin’s actual beliefs? This knotty question is, strictly speaking, unanswerable, since only he knows his own soul. Putin’s powerful Chekism is beyond doubt, while many Westerners are skeptical that he is any sort of Orthodox believer. According to his own account, Putin’s father was a militant Communist while his mother was a faithful, if quiet, Orthodox believer; one wonders what holidays were like in the Putin household. He was baptized in secret as a child but was not any sort of engaged believer during his KGB service — that would have been impossible, not least due to the KGB’s role in persecuting religion — but by his own account, late in the Soviet period, Putin reconciled his Chekism with his faith by making the sign of the cross over his KGB credentials. By the late 1990’s, Putin was wearing his baptismal cross openly, for all bare-chested photo ops.

The turn to faith in middle-age, after some sort of life crisis, is a staple of conversion and reversion stories. In his last years in power, Saddam Hussein began talking a lot about Islam openly, which was dismissed as political theater in the West, but in retrospect seems to have been at least somewhat sincere. Did Putin opt for Orthodoxy after a mid-life crisis? I am an Orthodox believer myself and, having carefully watched many video clips of Putin in church and at religious events, I can state without reservation that Putin knows what to do. His religious act — kissing icons, lighting candles, interacting with clerics — is flawless, so Putin is either a sincere Orthodox or he has devoted serious study to looking and acting like one.

Whether this faith is genuine or a well-honed pose, Putin’s potent fusion of KGB values and Orthodoxy has been building for years, though few Westerners have noticed. Early in Putin’s years in the Kremlin, the younger generation of Federal Security Service (FSB) officers embraced a nascent ideology they termed “the system” (sistema), which was a sort of elitist Chekism — toughness free of corruption and based in patriotism — updated for the new 21st century. However, this could have limited appeal to the masses, so its place was gradually taken by a doctrine termed “spiritual security.” This involved the ideological fusion of the FSB and the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), culminating in the 2002 dedication of an Orthodox church at the Lubyanka, the FSB — and former KGB’s — notorious Moscow headquarters. It suddenly became fashionable for senior FSB officers to have conversion experiences, while “spiritual security” offered Putin’s Russia a way to defend itself against what it has long seen as the encroachment of decadent post-modern Western values. Just how seriously Putin took all this was his statement that Russia’s “spiritual shield” was as important to her security as her nuclear shield.

Nearly all Western experts, being mostly secularists when not atheists, paid no attention to these clear indications of where Putin was taking Russia, while the view of the few who did notice was colored by the perception that this simply had to be a put-up job by the Kremlin. But what if it is not? Skeptics are correct to note that Chekists have had a toxic and convoluted relationship with the ROC ever since Stalin, that failed Orthodox seminarian, resurrected the remnants of the Church, what little had survived vicious Bolshevik persecution, during the darkest days of the Great Patriotic War to buttress the regime with faith and patriotism — all tightly controlled by the secret police. There was the rub. Under the Soviets, all senior ROC appointments were subject to Chekist review, while nobody became a bishop without the KGB having some kompromat on him. This was understood by all, including the fact that a distressing number of ROC senior clerics were actual KGB agents. It’s not surprising that Putin omits from his CV that he worked for a time in the KGB’s Fifth Directorate, which supervised religious bodies, leading some to speculate that Putin’s relationship with certain ROC bishops extends deep into the late Soviet period.

The ROC is not Russia’s state religion, as Putin and top bishops have been at pains to state, but it cannot be denied that the Moscow Patriarchate’s close ties to the Kremlin grant it a very special relationship with Putinism. Whether this actually is symphonia, meaning the Byzantine-style unity of state and church which is something of an Orthodox ideal, in stark contrast to American notions of separation of church and state, remains to be seen, but Orthodoxy has become the close political and ideological partner of the Kremlin in recent years, a preferred vehicle for explicit anti-Western propaganda.

ROC agitprop, which has Kremlin endorsement, depicts a West that is declining down to its death at the hands of decadence and sin, mired in confused unbelief, bored and failing to even reproduce itself. Patriarch Kirill, head of the church, recently explained that the “main threat” to Russia is “the loss of faith” in the Western style, while ROC spokesmen constantly denounce feminism and the LGBT movement as Satanic creations of the West that aim to destroy faith, family, and nation. It is in this context that Putin’s comments at last year’s Valdai Club event ought to be seen:

Another serious challenge to Russia’s identity is linked to events taking place in the world. Here there are both foreign policy and moral aspects. We can see how many of the Euro-Atlantic countries are actually rejecting their roots, including the Christian values that constitute the basis of Western civilization. They are denying moral principles and all traditional identities: national, cultural, religious and even sexual. They are implementing policies that equate large families with same-sex partnerships, belief in God with the belief in Satan.

The excesses of political correctness have reached the point where people are seriously talking about registering political parties whose aim is to promote pedophilia. People in many European countries are embarrassed or afraid to talk about their religious affiliations. Holidays are abolished or even called something different; their essence is hidden away, as is their moral foundation. And people are aggressively trying to export this model all over the world. I am convinced that this opens a direct path to degradation and primitivism, resulting in a profound demographic and moral crisis.

Part 2: Putin’s Attack on Ukraine Is a Religious War. Incredible insight to the schism of Russian orthodoxy

This week the ideological ante was upped by the Kremlin with the comments of Fr. Vsevolod Chaplin, a media gadfly cleric, who gave a very long newspaper interview in which he castigated, among other things, radical Islam, usury, and the West generally, but it was his comments on the current conflict with America that got all the attention. Chaplin minced no words, proclaiming that Russia’s God-given goal today is halting the global “American project.” As he explained:

It is no coincidence that we have often, at the price of our own lives … stopped all global projects that disagreed with our conscience, with our vision of history and, I would say, with God’s own truth .. Such was Napoleon’s project, such was Hitler’s project. We will stop the American project too.”

Chaplin added the usual tropes about Western decadence compared to Russian spiritual strength, waxing nationalist and Orthodox in a manner much like Putin has done many times. This interview was viewed as strange by most Westerners, but it must be realized that Chaplin, for all his inflammatory statements, is hardly some lone cleric talking crazy. He is the official spokesman of the Moscow Patriarchate who has a very close relationship with Patriarch Kirill; he appears in the media regularly and has received a raft of decorations from the ROC and the Russian state.

The forty-six year old Chaplin regularly makes statements that reflect a patriotic and religiously hardline stance on, well, everything. To cite only a few of his utterances to the media, Chaplin recently denounced a Hobbit movie promotion in Moscow as a Satanic symbol that would bring evil to the city; he stated that the p*ssy Riot case was proof that “The West gives its support to divide the people of Russia”; he advocated a national dress code for Russia, citing rising immorality (“It is wrong to think that women should decide themselves what they can wear in public places or at work … If a woman dresses like a prostitute, her colleagues must have the right to tell her that.”); and he has been particularly vocal in his opposition to Western-backed homosexuality: “it is one of the gravest sins because it changes people’s mental state, makes the creation of a normal family impossible, and corrupts the younger generation. By the way, it is no accident that the propaganda of this sin is targeted at young people and sometimes at children. It deprives people of eternal bliss.”

Chaplin’s biggest theme is that the decadent, post-modern West, led by the frankly Satanic United States — whose separation of church and state, per Chaplin, constitutes “a monstrous phenomenon that has occurred only in Western civilization and will kill the West, both politically and morally” — has no future. According to the ROC, speaking through its spokesman, the triumph of same-sex marriage means that the West doesn’t even have fifty years left before its collapse, and it will be up to Russia then to save what can be saved, to “make Europe Christian again, that is, go back to the ideals that once made Europe.”

While it is tempting to dismiss such talk as ravings, even when they come from the official spokesman of Putin’s own church, they have deep resonance with more serious thinkers whom Putin admires. Ivan Ilyin, a Russian philosopher who fled the Bolsheviks and died in Swiss exile, was reburied at Moscow’s famous Donskoy monastery in 2005 with public fanfare; Putin personally paid for Ilyin’s new headstone. Despite the fact that even Kremlin outlets note the importance of Ilyin to Putin’s worldview, not enough Westerners have paid attention.

They should. A devout Orthodox, Ilyin espoused a unique vision, a Slavophile take on modernity and Russia’s predicament under the militant atheists. He espoused ethnic-religious neo-traditionalism, amidst much talk about a unique “Russian soul.” Of greatest relevance today, he believed that Russia would recover from the Bolshevik nightmare and rediscover itself, first spiritually then politically, thereby saving the world. Ilyin’s take on responsibility for Bolshevism — and its cure — merits examination, as he explained:

The West exported this anti-Christian virus to Russia … Having lost our bond with God and the Christian Tradition, mankind has been morally blinded, gripped by materialism, irrationalism and nihilism … In order to overcome the global moral crisis, we have to return to eternal moral values, that is faith, love, freedom, conscience, family, motherland and nation, but above all faith and love.

Although Ilyin died sixty years ago, he remains to his admirers “the prophet of the new Orthodox Russia which is being born and which alone can give the contemporary world a viable future, providing that it is given time to grow to fruition in contemporary Russia.” As Ilyin wrote to a friend near the end of his life, when the fall of Communism was still decades off:

What are we to do, squeezed between Catholics, Freemasons and Bolsheviks? I answer: Stand firm, standing up with your left hand, which goes from the heart, for Christ the Lord, for His undivided tunic, and, with your right hand, fight to the end for Orthodoxy and Orthodox Russia. And, above all, vigilantly watch those groups which are preparing for Antichrist. All of this – even if we are threatened by apparent complete powerlessness and total solitude.

The sort of uncompromising faith Ilyin stood for, which bears little similarity to Western Christianity much less to post-modern notions of “tolerance,” is made abundantly clear in his numerous writings and speeches. Of particular interest is a speech Ilyin gave in 1925, extolling Lavr Kornilov, a White Russian general who fell in the struggle against Bolshevism (and, not coincidentally, exactly the sort of Orthodox-believing yet non-noble White counter-revolutionary figure much admired by Putin). Ilyin defined what Russia and Orthodoxy now needed: “This idea is more than a single man, more than a feat of one hero. This idea is great as Russia and the sacred as her religion. This is the idea of the Orthodox sword.” He cited the fatal shortcomings of pre-revolutionary Russia as “limp sentimentality, spiritual nihilism and moral pedantry,” and to counter those Russia needed a strong dose of fighting faith. As Ilyin explained:

In calling to love our enemies, Christ had in mind personal enemies of man, not God’s enemies, and not blaspheming molesters, for them drowning with a millstone around their neck was recommended. Urging to forgive injuries, Christ was referring to personal insults to a person, not all possible crimes; no one has the right to forgive the offenses suffered by others or provide for the villains to offend the weak, corrupt children, desecrate churches and destroy the Fatherland. So therefore a Christian is called not only to forgive offenses, but to fight the enemies of God’s work on earth. The evangelical commandment of “non-resistance to evil” teaches humility and generosity in personal matters, and not limpness of will, not cowardice, not treachery and not obedience to evildoers.

This is the vision — uncompromising faith and patriotism, without any sentimentality or weakness — that animates Russia’s holy warriors today, from Fr. Chaplin, and perhaps Vladimir Putin too, on down. Russian Orthodoxy’s church militant is a special breed that tends to mystify Westerners. Certainly the West finds the motley crew of Kremlin-backed Orthodox adventurers and mercenaries battling in the Donbass to be equal parts comical and sinister, yet they have an ideology which they hardly hide. As an Orthodox priest ministering to Russian fighters in Donetsk explained a few months ago — a bearded cleric and tough veteran of the Soviet Afghan war, he is a creature straight out of Ilyin’s dreams — what they are battling against is not the Ukrainian government, nor American neoconservatives, rather the Devil himself. The goal of Moscow’s enemy, as he elaborated, is perfectly clear to the eyes of faith:

The establishment of planetary Satanic rule. What’s occurring here is the very beginning of a global war. Not for resources or territory, that’s secondary. This is a war for the destruction of true Christianity, Orthodoxy. The worldview of the wealthiest men who own almost all the material goods in the world is Satanism. Having summoned the elements of the First and Second World Wars and a Third Information War, and having laid hundreds of millions of the slain at the altar of their father, Satan, they have initiated the Fourth World War. They are intentionally hastening the reign of Antichrist.

As with Vsevolod Chaplin, it’s tempting to dismiss all this as the ravings of a lone nut, but these are no longer fringe views in Putin’s Russia. Jihad is not a word to be used lightly, given its sinister connotations to the West after 9/11, but this bears more than a little resemblance to Holy War in a Russian and Orthodox variant. Whether Putin really believes all this may be immaterial, since his regime has created and nurtured a virulent ideology, an explosive amalgam of xenophobia, Chekism and militant Orthodoxy which justifies the Kremlin’s actions and explains why the West must be opposed at all costs. Given the economic crisis that Russia now finds itself in, thanks to Western sanctions, during the long and cold winter now starting, we ought to expect more, not fewer, Russians turning to this worldview which resonates with their nation’s history and explains the root of their suffering.

We perhaps should be grateful that the Orthodox Jihad rejects suicide bombings. In the 1930’s, Romania’s fascist Legionary Movement, led by the charismatic Orthodox revolutionary Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, toyed with what terrorism mavens today might term “martyrdom operations,” but these never really caught on. Orthodoxy frowns on suicide, even in a just cause. That, at least, is the good news.

The bad news, however, is that Putin’s uncompromising worldview has more than a few admirers in the West, far beyond the Orthodox realm. Many who reject Moscow’s quasi-religious mysticism nevertheless admire its willingness to take on America directly and offer a counterpoint to armed post-modernism in world affairs. As I’ve previously explained, many European far-right parties have quite a crush on the man in the Kremlin, perhaps due to the money he gives them, but the sincerity of some of the admiration is not in question. In France, Marine Le Pen is leading her National Front to ever-greater heights of political power, and her affection for Putin is unconcealed. “In Russia today there is a mix of exalting nationalism, exalting the church and Christian values,” explained a French politico: “They are now replacing the red star with the cross, and they are representing themselves as the ultimate barrier against the Islamization of the continent.” Since it is far from impossible that Le Pen will be president of France someday, the implications of all this for NATO and the West merit serious consideration.

It would be supremely ironic if the last defender of Europe and European values comes from the East, from a Kremlin controlled by a former KGB officer who mourns the collapse of the Soviet Union yet has rediscovered traditional faith and family values. As discontentment with American-led Europe spreads, the Russian option may look plausible to more Europeans, worried about immigration, identity, and the collapse of their values and economies, than Americans might imagine. Ivan Ilyin, however, might not be surprised by this strange turn of events in the slightest.

This week the ideological ante was upped by the Kremlin with the comments of Fr. Vsevolod Chaplin, a media gadfly cleric, who gave a very long newspaper interview in which he castigated, among other things, radical Islam, usury, and the West generally, but it was his comments on the current conflict with America that got all the attention. Chaplin minced no words, proclaiming that Russia’s God-given goal today is halting the global “American project.” As he explained:

It is no coincidence that we have often, at the price of our own lives … stopped all global projects that disagreed with our conscience, with our vision of history and, I would say, with God’s own truth .. Such was Napoleon’s project, such was Hitler’s project. We will stop the American project too.”

Chaplin added the usual tropes about Western decadence compared to Russian spiritual strength, waxing nationalist and Orthodox in a manner much like Putin has done many times. This interview was viewed as strange by most Westerners, but it must be realized that Chaplin, for all his inflammatory statements, is hardly some lone cleric talking crazy. He is the official spokesman of the Moscow Patriarchate who has a very close relationship with Patriarch Kirill; he appears in the media regularly and has received a raft of decorations from the ROC and the Russian state.

The forty-six year old Chaplin regularly makes statements that reflect a patriotic and religiously hardline stance on, well, everything. To cite only a few of his utterances to the media, Chaplin recently denounced a Hobbit movie promotion in Moscow as a Satanic symbol that would bring evil to the city; he stated that the p*ssy Riot case was proof that “The West gives its support to divide the people of Russia”; he advocated a national dress code for Russia, citing rising immorality (“It is wrong to think that women should decide themselves what they can wear in public places or at work … If a woman dresses like a prostitute, her colleagues must have the right to tell her that.”); and he has been particularly vocal in his opposition to Western-backed homosexuality: “it is one of the gravest sins because it changes people’s mental state, makes the creation of a normal family impossible, and corrupts the younger generation. By the way, it is no accident that the propaganda of this sin is targeted at young people and sometimes at children. It deprives people of eternal bliss.”

Chaplin’s biggest theme is that the decadent, post-modern West, led by the frankly Satanic United States — whose separation of church and state, per Chaplin, constitutes “a monstrous phenomenon that has occurred only in Western civilization and will kill the West, both politically and morally” — has no future. According to the ROC, speaking through its spokesman, the triumph of same-sex marriage means that the West doesn’t even have fifty years left before its collapse, and it will be up to Russia then to save what can be saved, to “make Europe Christian again, that is, go back to the ideals that once made Europe.”

While it is tempting to dismiss such talk as ravings, even when they come from the official spokesman of Putin’s own church, they have deep resonance with more serious thinkers whom Putin admires. Ivan Ilyin, a Russian philosopher who fled the Bolsheviks and died in Swiss exile, was reburied at Moscow’s famous Donskoy monastery in 2005 with public fanfare; Putin personally paid for Ilyin’s new headstone. Despite the fact that even Kremlin outlets note the importance of Ilyin to Putin’s worldview, not enough Westerners have paid attention.

They should. A devout Orthodox, Ilyin espoused a unique vision, a Slavophile take on modernity and Russia’s predicament under the militant atheists. He espoused ethnic-religious neo-traditionalism, amidst much talk about a unique “Russian soul.” Of greatest relevance today, he believed that Russia would recover from the Bolshevik nightmare and rediscover itself, first spiritually then politically, thereby saving the world. Ilyin’s take on responsibility for Bolshevism — and its cure — merits examination, as he explained:

The West exported this anti-Christian virus to Russia … Having lost our bond with God and the Christian Tradition, mankind has been morally blinded, gripped by materialism, irrationalism and nihilism … In order to overcome the global moral crisis, we have to return to eternal moral values, that is faith, love, freedom, conscience, family, motherland and nation, but above all faith and love.

Although Ilyin died sixty years ago, he remains to his admirers “the prophet of the new Orthodox Russia which is being born and which alone can give the contemporary world a viable future, providing that it is given time to grow to fruition in contemporary Russia.” As Ilyin wrote to a friend near the end of his life, when the fall of Communism was still decades off:

What are we to do, squeezed between Catholics, Freemasons and Bolsheviks? I answer: Stand firm, standing up with your left hand, which goes from the heart, for Christ the Lord, for His undivided tunic, and, with your right hand, fight to the end for Orthodoxy and Orthodox Russia. And, above all, vigilantly watch those groups which are preparing for Antichrist. All of this – even if we are threatened by apparent complete powerlessness and total solitude.

The sort of uncompromising faith Ilyin stood for, which bears little similarity to Western Christianity much less to post-modern notions of “tolerance,” is made abundantly clear in his numerous writings and speeches. Of particular interest is a speech Ilyin gave in 1925, extolling Lavr Kornilov, a White Russian general who fell in the struggle against Bolshevism (and, not coincidentally, exactly the sort of Orthodox-believing yet non-noble White counter-revolutionary figure much admired by Putin). Ilyin defined what Russia and Orthodoxy now needed: “This idea is more than a single man, more than a feat of one hero. This idea is great as Russia and the sacred as her religion. This is the idea of the Orthodox sword.” He cited the fatal shortcomings of pre-revolutionary Russia as “limp sentimentality, spiritual nihilism and moral pedantry,” and to counter those Russia needed a strong dose of fighting faith. As Ilyin explained:

In calling to love our enemies, Christ had in mind personal enemies of man, not God’s enemies, and not blaspheming molesters, for them drowning with a millstone around their neck was recommended. Urging to forgive injuries, Christ was referring to personal insults to a person, not all possible crimes; no one has the right to forgive the offenses suffered by others or provide for the villains to offend the weak, corrupt children, desecrate churches and destroy the Fatherland. So therefore a Christian is called not only to forgive offenses, but to fight the enemies of God’s work on earth. The evangelical commandment of “non-resistance to evil” teaches humility and generosity in personal matters, and not limpness of will, not cowardice, not treachery and not obedience to evildoers.

This is the vision — uncompromising faith and patriotism, without any sentimentality or weakness — that animates Russia’s holy warriors today, from Fr. Chaplin, and perhaps Vladimir Putin too, on down. Russian Orthodoxy’s church militant is a special breed that tends to mystify Westerners. Certainly the West finds the motley crew of Kremlin-backed Orthodox adventurers and mercenaries battling in the Donbass to be equal parts comical and sinister, yet they have an ideology which they hardly hide. As an Orthodox priest ministering to Russian fighters in Donetsk explained a few months ago — a bearded cleric and tough veteran of the Soviet Afghan war, he is a creature straight out of Ilyin’s dreams — what they are battling against is not the Ukrainian government, nor American neoconservatives, rather the Devil himself. The goal of Moscow’s enemy, as he elaborated, is perfectly clear to the eyes of faith:

The establishment of planetary Satanic rule. What’s occurring here is the very beginning of a global war. Not for resources or territory, that’s secondary. This is a war for the destruction of true Christianity, Orthodoxy. The worldview of the wealthiest men who own almost all the material goods in the world is Satanism. Having summoned the elements of the First and Second World Wars and a Third Information War, and having laid hundreds of millions of the slain at the altar of their father, Satan, they have initiated the Fourth World War. They are intentionally hastening the reign of Antichrist.

As with Vsevolod Chaplin, it’s tempting to dismiss all this as the ravings of a lone nut, but these are no longer fringe views in Putin’s Russia. Jihad is not a word to be used lightly, given its sinister connotations to the West after 9/11, but this bears more than a little resemblance to Holy War in a Russian and Orthodox variant. Whether Putin really believes all this may be immaterial, since his regime has created and nurtured a virulent ideology, an explosive amalgam of xenophobia, Chekism and militant Orthodoxy which justifies the Kremlin’s actions and explains why the West must be opposed at all costs. Given the economic crisis that Russia now finds itself in, thanks to Western sanctions, during the long and cold winter now starting, we ought to expect more, not fewer, Russians turning to this worldview which resonates with their nation’s history and explains the root of their suffering.

We perhaps should be grateful that the Orthodox Jihad rejects suicide bombings. In the 1930’s, Romania’s fascist Legionary Movement, led by the charismatic Orthodox revolutionary Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, toyed with what terrorism mavens today might term “martyrdom operations,” but these never really caught on. Orthodoxy frowns on suicide, even in a just cause. That, at least, is the good news.

The bad news, however, is that Putin’s uncompromising worldview has more than a few admirers in the West, far beyond the Orthodox realm. Many who reject Moscow’s quasi-religious mysticism nevertheless admire its willingness to take on America directly and offer a counterpoint to armed post-modernism in world affairs. As I’ve previously explained, many European far-right parties have quite a crush on the man in the Kremlin, perhaps due to the money he gives them, but the sincerity of some of the admiration is not in question. In France, Marine Le Pen is leading her National Front to ever-greater heights of political power, and her affection for Putin is unconcealed. “In Russia today there is a mix of exalting nationalism, exalting the church and Christian values,” explained a French politico: “They are now replacing the red star with the cross, and they are representing themselves as the ultimate barrier against the Islamization of the continent.” Since it is far from impossible that Le Pen will be president of France someday, the implications of all this for NATO and the West merit serious consideration.

It would be supremely ironic if the last defender of Europe and European values comes from the East, from a Kremlin controlled by a former KGB officer who mourns the collapse of the Soviet Union yet has rediscovered traditional faith and family values. As discontentment with American-led Europe spreads, the Russian option may look plausible to more Europeans, worried about immigration, identity, and the collapse of their values and economies, than Americans might imagine. Ivan Ilyin, however, might not be surprised by this strange turn of events in the slightest.

tried telling yall... its levels to this shyt

rferl.org

Orthodox Clerics Call For Stop To War In Ukraine In Rare Challenge To Russian Government

It is very rare for such a large number of religious clerics of the Orthodox Church to openly challenge President Vladimir Putin (right). In recent years, the Russian Orthodox Church and its leader, Patriarch Kirill (left), who did not sign the letter, have fully supported Putin's policies.

In an unusual move, more than 150 Russian Orthodox clerics have called for an immediate stop to the ongoing war in Ukraine in an open letter issued on March 1.

At least 176 Orthodox clerics said that they "respect the freedom of any person given to him or her by God," adding that the people of Ukraine "must make their own choices by themselves, not at the point of assault rifles and without pressure from either West or East."

Live Briefing: Russia Invades Ukraine

Check out RFE/RL's live briefing on Russia's invasion of Ukraine and how Kyiv is fighting and the West is reacting. The briefing presents the latest developments and analysis, updated throughout the day.

The letter says the clerics “bewail” the suffering that has been “undeservingly imposed on our brothers and sisters in Ukraine.”

It is very rare for such a large number of religious clerics of the Orthodox Church to openly challenge President Vladimir Putin's government. In recent years, the Russian Orthodox Church and its leader, Patriarch Kirill, who did not sign the letter, have fully supported Putin's policies.

"We call on all opposing sides for a dialogue because there is no other alternative to violence,” the letter says. “Only an ability to hear the other side can give us hope to get out of the abyss our countries were thrown into several days ago. Let yourself and us all enter the Easter Lent in the spirit of faith and love. Stop the war."

There was no comment or other reaction from Patriarch Kirill or from Russian officials.

The letter makes references to "judgment day” and “eternal suffering,” saying nothing on Earth can prevent that judgment.

“We remind that Christ's blood shed by the Savior for the world's life will be taken in the celebration of the Communion by those who gives murderous orders, not as life, but as eternal suffering.”

rferl.org

Orthodox Clerics Call For Stop To War In Ukraine In Rare Challenge To Russian Government

It is very rare for such a large number of religious clerics of the Orthodox Church to openly challenge President Vladimir Putin (right). In recent years, the Russian Orthodox Church and its leader, Patriarch Kirill (left), who did not sign the letter, have fully supported Putin's policies.

In an unusual move, more than 150 Russian Orthodox clerics have called for an immediate stop to the ongoing war in Ukraine in an open letter issued on March 1.

At least 176 Orthodox clerics said that they "respect the freedom of any person given to him or her by God," adding that the people of Ukraine "must make their own choices by themselves, not at the point of assault rifles and without pressure from either West or East."

Live Briefing: Russia Invades Ukraine

Check out RFE/RL's live briefing on Russia's invasion of Ukraine and how Kyiv is fighting and the West is reacting. The briefing presents the latest developments and analysis, updated throughout the day.

The letter says the clerics “bewail” the suffering that has been “undeservingly imposed on our brothers and sisters in Ukraine.”

It is very rare for such a large number of religious clerics of the Orthodox Church to openly challenge President Vladimir Putin's government. In recent years, the Russian Orthodox Church and its leader, Patriarch Kirill, who did not sign the letter, have fully supported Putin's policies.

"We call on all opposing sides for a dialogue because there is no other alternative to violence,” the letter says. “Only an ability to hear the other side can give us hope to get out of the abyss our countries were thrown into several days ago. Let yourself and us all enter the Easter Lent in the spirit of faith and love. Stop the war."

There was no comment or other reaction from Patriarch Kirill or from Russian officials.

The letter makes references to "judgment day” and “eternal suffering,” saying nothing on Earth can prevent that judgment.

“We remind that Christ's blood shed by the Savior for the world's life will be taken in the celebration of the Communion by those who gives murderous orders, not as life, but as eternal suffering.”

theconversation.com

Holy wars: How a cathedral of guns and glory symbolizes Putin’s Russia

Lena Surzhko Harned

7-9 minutes

A curious new church was dedicated on the outskirts of Moscow in June 2020: The Main Church of the Russian Armed Forces. The massive, khaki-colored cathedral in a military theme park celebrates Russian might. It was originally planned to open on the 75th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany, in May 2020, but was delayed due to the pandemic.

Conceived by the Russian defense minister after the country’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, the cathedral embodies the powerful ideology espoused by President Vladimir Putin, with strong support from the Russian Orthodox Church.

The Kremlin’s vision of Russia connects the state, military and the Russian Orthodox Church. As a scholar of nationalism, I see this militant religious nationalism as one of the key elements in Putin’s motivation for the invasion of Ukraine, my native country. It also goes a long way in explaining Moscow’s behavior toward the collective “West” and the post-Cold War world order.

Angels and guns

The Church of the Armed Forces’ bell tower is 75 meters tall, symbolizing the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Its dome’s diameter is 19.45 meters, marking the year of the victory: 1945. A smaller dome is 14.18 meters, representing the 1,418 days the war lasted. Trophy weapons are melted into the floor so that each step is a blow to the defeated Nazis.

Frescoes celebrate Russia’s military might though history, from medieval battles to modern-day wars in Georgia and Syria. Archangels lead heavenly and earthly armies, Christ wields a sword, and the Holy Mother, depicted as the Motherland, lends support.

Service members and young army cadets gather for an event held outside the cathedral to mark the 80th anniversary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in World War II. Gavriil Grigorov\TASS via Getty Images

‘Cradles’ of Christianity

The original plans for the frescoes included a celebration of the Crimean occupation, with jubilant people holding a banner that read “Crimea is Ours” and “Forever with Russia.” In the final version, the controversial “Crimea is Ours” was replaced by the more benign “We are together.”

When Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine in 2014, the Russian Orthodox Church celebrated, calling Crimea the “cradle” of Russian Christianity. This mythology draws on the medieval story of Prince Vladimir, who converted to Christianity in the 10th century and was baptized in Crimea. The prince then imposed the faith on his subjects in Kyiv, and it spread from there.

The Russian Orthodox Church, also called the Moscow Patriarchate, has long claimed this event as its foundational story. The Russian Empire, which linked itself to the church, adopted this foundational story as well.

‘Russian World’

Putin and the head of the Russian church, Patriarch Kirill, have resurrected these ideas about empire for the 21st century in the form of the so-called “Russian World” – giving new meaning to a phrase that dates to medieval times.

In 2007, Putin created a Russian World Foundation, which was charged with promotion of Russian language and culture worldwide, such as a cultural project preserving interpretations of history approved by the Kremlin.

For church and state, the idea of “Russian World” encompasses a mission of making Russia a spiritual, cultural and political center of civilization to counter the liberal, secular ideology of the West. This vision has been used to justify policies at home and abroad.

The Great Patriotic War

Another planned mosaic depicted the celebrations of Soviet forces’ defeat of Nazi Germany – the Great Patriotic War, as World War II is called in Russia. The image included soldiers holding a portrait of Josef Stalin, the dictator who led the USSR during the war, among a crowd of decorated veterans. This mosaic was reportedly removed before the church’s opening.

The Great Patriotic War has a special, even sacred, place in Russians’ views of history. The Soviet Union sustained immense losses – 26 million lives is a conservative estimate. Apart from the sheer devastation, many Russians ultimately see the war as a holy one, in which Soviets defended their motherland and the whole world from the evil of Nazism.

Under Putin, glorification of the war and Stalin’s role in the victory have reached epic proportions. Nazism, for very good reasons, is seen as a manifestation of the ultimate evil.

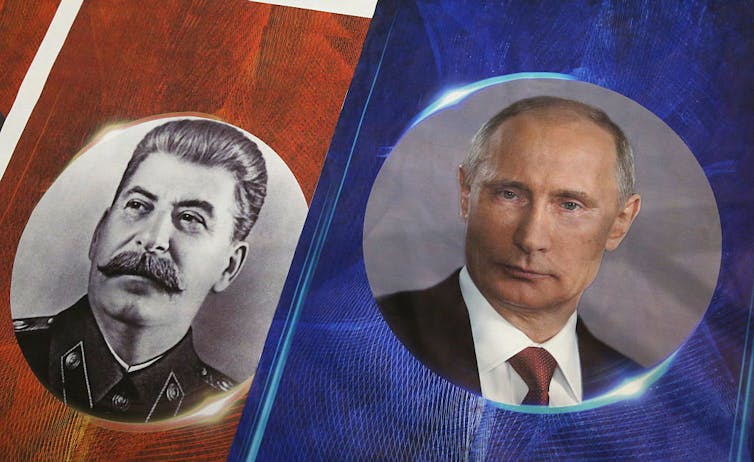

Portraits of Soviet leader Josef Stalin (left) and Russian President Vladimir Putin on display at the opening of an exhibit called Russia - My History, 1945-2016, at Moscow’s Manege Central Exhibition Hall. Valery Sharifulin\TASS via Getty Images