What data are you concerned about being in a database? It's a simple question

any data, for the simple fact that you can never predict how it can be used to harm you at a later date. people who thought innocent pictures and video recordings they shared online were harmless but now it's being used by criminals employing AI to scam unsuspecting family and friends. 23 and me got hacked and a specific database for jewish dna was put up for sale.

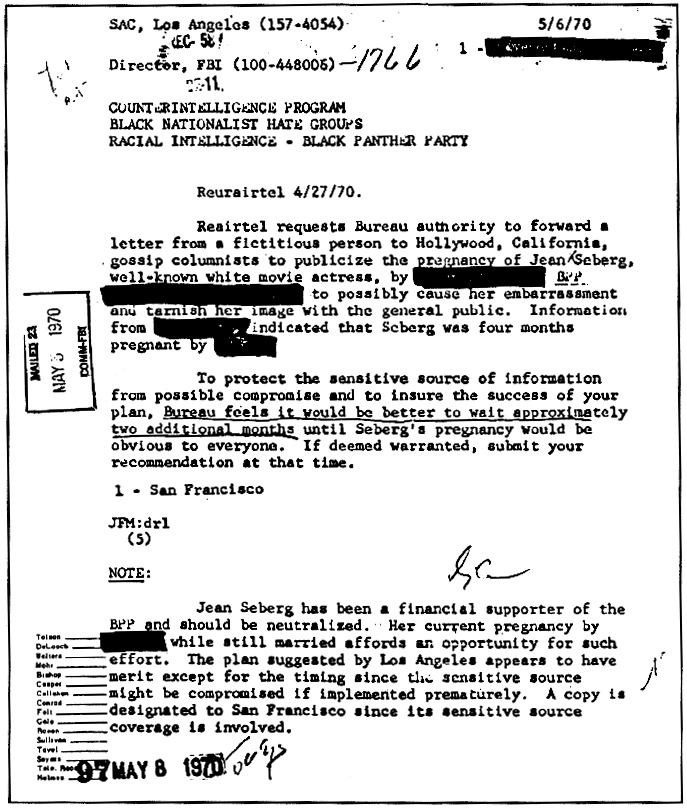

COINTELPRO - Wikipedia

AP: Across US, police officers abuse confidential databases

An investigation by The Associated Press finds that scores of police officers are abusing confidential law enforcement databases.

A look at police abuse of confidential databases nationwide

An Associated Press investigation found scores of police officers abuse confidential law enforcement databases every year to get information about ex-romantic partners, business associates, neighbors and even journalists for reasons that have nothing to do with daily police work.

BY SADIE GURMAN AND ERIC TUCKER

Published 12:28 AM EDT, September 28, 2016

Share

DENVER (AP) — Police officers across the country misuse confidential law enforcement databases to get information on romantic partners, business associates, neighbors, journalists and others for reasons that have nothing to do with daily police work, an Associated Press investigation has found.

Criminal-history and driver databases give officers critical information about people they encounter on the job. But the AP’s review shows how those systems also can be exploited by officers who, motivated by romantic quarrels, personal conflicts or voyeuristic curiosity, sidestep policies and sometimes the law by snooping. In the most egregious cases, officers have used information to stalk or harass, or have tampered with or sold records they obtained.

No single agency tracks how often the abuse happens nationwide, and record-keeping inconsistencies make it impossible to know how many violations occur.

But the AP, through records requests to state agencies and big-city police departments, found law enforcement officers and employees who misused databases were fired, suspended or resigned more than 325 times between 2013 and 2015. They received reprimands, counseling or lesser discipline in more than 250 instances, the review found.

Unspecified discipline was imposed in more than 90 instances reviewed by AP. In many other cases, it wasn’t clear from the records if punishment was given at all. The number of violations was surely far higher since records provided were spotty at best, and many cases go unnoticed.

Among those punished: an Ohio officer who pleaded guilty to stalking an ex-girlfriend and who looked up information on her; a Michigan officer who looked up home addresses of women he found attractive; and two Miami-Dade officers who ran checks on a journalist after he aired unflattering stories about the department.

“It’s personal. It’s your address. It’s all your information, it’s your Social Security number, it’s everything about you,” said Alexis Dekany, the Ohio woman whose ex-boyfriend, a former Akron officer, pleaded guilty last year to stalking her. “And when they use it for ill purposes to commit crimes against you — to stalk you, to follow you, to harass you ... it just becomes so dangerous.”

The misuse represents only a tiny fraction of the millions of daily database queries run legitimately during traffic stops, criminal investigations and routine police encounters. But the worst violations profoundly abuses systems that supply vital information on criminal suspects and law-abiding citizens alike. The unauthorized searches demonstrate how even old-fashioned policing tools are ripe for abuse, at a time when privacy concerns about law enforcement have focused mostly on more modern electronic technologies. And incomplete, inconsistent tracking of the problem frustrates efforts to document its pervasiveness.

The AP tally, based on records requested from 50 states and about three dozen of the nation’s largest police departments, is unquestionably an undercount.

Some departments produced no records at all. Some states refused to disclose the information, said they don’t comprehensively track misuse or produced records too incomplete or unclear to be counted. Florida reported hundreds of misuse cases of its driver database, but didn’t say how often officers were disciplined.

And some cases go undetected, officials say, because there aren’t clear red flags to automatically distinguish questionable searches from legitimate ones.

“If we know the officers in a particular agency have made 10,000 queries in a month, we just have no way to (know) they were for an inappropriate reason unless there’s some consequence where someone might complain to us,” said Carol Gibbs, database administrator with the Illinois State Police.

The AP’s requests encompassed state and local databases and the FBI-administered National Crime and Information Center, a searchable clearinghouse that processes an average of 14 million daily transactions.

The NCIC catalogs information that officers enter on sex offenders, immigration violators, suspected gang members, people with outstanding warrants and individuals reported missing, among others. Police use the system to locate fugitives, identify missing people and determine if a motorist they’ve stopped is driving a stolen car or is wanted elsewhere.

Other statewide databases offer access to criminal histories and motor vehicle records, birth dates and photos.

Officers are instructed that those systems, which together contain data far more substantial than an internet search would yield, may be used only for legitimate law enforcement purposes. They’re warned that their searches are subject to being audited and that unauthorized access could cost them their jobs or result in criminal charges.

Yet misuse persists.

____

‘SENSE OF BEING VULNERABLE’

Violations frequently arise from romantic pursuits or domestic entanglements, including when a Denver officer became acquainted with a hospital employee during a sex-assault investigation, then searched out her phone number and called her at home. A Mancos, Colorado, marshal asked co-workers to run license plate checks for every white pickup truck they saw because his girlfriend was seeing a man who drove a white pickup, an investigative report shows.

In Florida, a Polk County sheriff’s deputy investigating a battery complaint ran driver’s license information of a woman he met and then messaged her unsolicited through Facebook.

Officers have sought information for purely personal purposes, including criminal records checks of co-workers at private businesses. A Phoenix officer ran searches on a neighbor during the course of a longstanding dispute. A North Olmsted, Ohio, officer pleaded guilty this year to searching for a female friend’s landlord and showing up in the middle of the night to demand the return of money he said was owed her.

The officer, Brian Bielozer, told the AP he legitimately sought the landlord’s information as a safety precaution to determine if she had outstanding warrants or a weapons permit. But he promised as part of a plea agreement never to seek a job again in law enforcement. He said he entered the plea to avoid mounting legal fees.

Some database misuse occurred in the course of other misbehavior, including a Phoenix officer who gave a woman involved in a drug and gun-trafficking investigation details about stolen cars in exchange for arranging sexual encounters for him. She told an undercover detective about a department source who could “get any information on anybody,” a disciplinary report says.

Eric Paull, the Akron police sergeant who pleaded guilty last year to stalking Dekany, also ran searches on her mother, men she’d been close with and students from a course he taught, prosecutors said. A lawyer for Paull, who was sentenced to prison, said Paull has accepted responsibility for his actions.

“A lot of people have complicated personal lives and very strong passions,” said Jay Stanley, an American Civil Liberties Union privacy expert. “There’s greed, there’s lust, there’s all the deadly sins. And often, accessing information is a way for people to act on those human emotions.”

Other police employees searched for family members, sometimes at relatives’ requests, to check what information was stored or to see if they were the subjects of warrants.

Still other searchers were simply curious, including a Miami-Dade officer who admitted checking dozens of officers and celebrities including basketball star LeBron James.

Political motives occasionally surface.

Deb Roschen, a former county commissioner in Minnesota, alleged in a 2013 lawsuit that law enforcement and government employees inappropriately ran repeated queries on her and other politicians over 10 years. The searches were in retaliation for questioning county spending and sheriff’s programs, she contended.

She filed an open-records request that revealed her husband and daughter were also researched, sometimes at odd hours. But an appeals court rejected her suit and several similar cases this month, saying the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate the searches were unpermitted.

“Now there are people who do not like me that have all my private information ... any information that could be used against me. They could steal my identity, they could sell it to someone,” Roschen said.

“The sense of being vulnerable,” she added, “there’s no fix to that.”

Here’s how police can get your data — even if you aren’t suspected of a crime

And you may never know they did it.

www.vox.com

www.vox.com