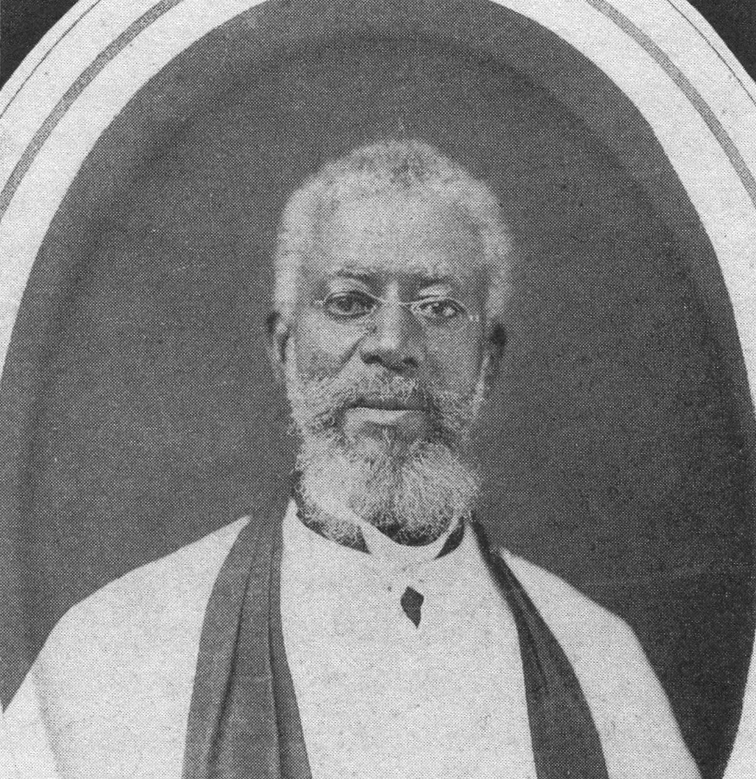

Henry McNeal Turner (1834-1915)

One of the most influential African American leaders in late-nineteenth-century Georgia,Henry McNeal Turner was a pioneering church organizer and missionary for the

African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in Georgia, later rising to the rank of bishop. Turner was also an active politician and

Reconstruction-era state

legislator from

Macon. Later in life, he became an outspoken advocate of back-to-Africa emigration.

Turner was born in 1834 in Newberry Courthouse, South Carolina, to Sarah Greer and Hardy Turner. Turner was never a slave. His paternal grandmother was a white plantation owner. His maternal grandfather, David Greer, arrived in North America aboard a slave ship but, according to family legend, was found to have a tattoo with the Mandingo coat of arms, signifying his royal status. The South Carolinians decided not to sell Greer into

slavery and sent him to live with a

Quaker family.

Against great odds, Turner managed to receive an education. An Abbeville, South Carolina, law firm employed him at age fifteen to do janitorial tasks, and the firm's

lawyers, appreciating his high intelligence, helped provide him with a well-rounded education. About a year earlier, Turner had been converted during a Methodist revival and decided he would one day become a preacher. After receiving his preacher's license in 1853, he traveled throughout the South as an itinerant evangelist, going as far as New Orleans, Louisiana. Much of his time was spent in Georgia, where he preached at revivals in Macon,

Athens, and

Atlanta. In 1856 he married Eliza Peacher, the daughter of a wealthy African American house builder in Columbia, South Carolina. They had fourteen children, only four of whom survived into adulthood.

In 1858 he and his family journeyed north to St. Louis, Missouri, where he was accepted as a preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Turner feared southern legislation threatening enslavement of free African Americans. For the next five years, he filled pastorates in Baltimore, Maryland, and in Washington, D.C., and witnessed the outbreak of the

Civil War (1861-65). During his time in Washington, he befriended Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, and other powerful Republican legislators. In 1863 Turner was instrumental in organizing the

First Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops in his own churchyard and was mustered into service as an army chaplain for that regiment. He and his regiment were involved in numerous battles in the Virginia theater.

At the war's end, U.S. president Andrew Johnson reassigned Turner to a black regiment in Atlanta, but Turner resigned when he realized it already had a chaplain. He spent much of the next three years traveling throughout Georgia, helping to organize the African Methodist Episcopal Church in what was virgin, but not always friendly, territory. African Americans flocked to the new denomination, but the lack of such essentials as trained pastors and adequate meeting space challenged Turner.

In 1867, after Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts, Turner switched his energies to the political sphere. He helped organize Georgia's Republican Party. He served in the state's

constitutional convention and then was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, representing Macon. In 1868, when the vast majority of white legislators decided to expel their African American peers on the grounds that officeholding was a privilege denied those from a servile background, Turner delivered an eloquent speech from the floor. Unfortunately, it did little to sway his fellow legislators. Soon afterward Turner received threats from the

Ku Klux Klan.

In 1869 he was appointed postmaster of Macon by U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant but was forced to resign a few weeks later under fire from allegations that he consorted with prostitutes and had passed defective currency. At the behest of the U.S. Congress, he did reclaim his legislative seat in 1870, but he was denied reelection in a fraud-filled contest a few months later. Turner moved to

Savannah, where he worked at the Custom House and served as a pastor of the prestigious St. Philip's AME Church. In 1876 he was elected manager of the publishing house of the church. Four years later, in a hard-fought and controversial contest, he won election as the twelfth bishop of the AME Church.

Turner was an extremely vigorous and successful bishop. In 1885 he became the first AME bishop to ordain a woman, Sarah Ann Hughes, to the office of deacon. He wrote

The Genius and Theory of Methodist Polity (1885), a learned guide to Methodist policies and practices. He twice entered the political ranks in support of prohibition referenda in Atlanta. After his wife, Eliza, died in 1889, Turner eventually married three more times: Martha Elizabeth DeWitt in 1893; Harriet A. Wayman in 1900; and Laura Pearl Lemon in 1907. Between 1891 and 1898, Turner traveled four times to Africa. He was instrumental in promoting the annual conferences in Liberia and Sierra Leone and in attaining a merger with the Ethiopian Church in South Africa. Turner also sought to promote the growth of the AME Church in Latin America, sending missionaries to Cuba and Mexico.

With the support of white businessmen from Alabama, Turner helped organize the International Migration Society to promote the return of African Americans to Africa. To further the emigrationist cause, he established his own newspapers:

The Voice of Missions (editor, 1893-1900) and later

The Voice of the People (editor, 1901-4). Two ships with a total of 500 or more emigrants sailed to Liberia in 1895 and 1896, but a number returned, complaining about disease and the country's poor economic prospects. Turner remained an advocate of back-to-Africa programs but was unable to make further headway against the negative reactions of returned emigrants. In his later years he felt increasingly estranged from the South.

Turner died on May 8, 1915, in Windsor, Canada, while traveling on church business. He is buried in Atlanta. A portrait of Turner hangs in the

state capitol.