ogc163

Superstar

Erin Richards

USA TODAY

NEW YORK – The holiday performances always gave it away.

Every December, as students at Public School 9 in Brooklyn stood to sing holiday songs while their parents looked on, one class would be made up of a lot of white students, followed by another class of almost all black students.

From the outside, the racial divide might seem curious as PS 9 is one of the most diverse elementary schools in Brooklyn: Out of about 940 students, 40% are black, 31% are white, 17% are Hispanic and 9% are Asian. But inside, many students spend their days learning in separate groups. The gifted and talented classes are attended by mostly white and Asian kids; the general education classes, mostly black students.

“It wasn’t obvious until you sat in the audience and watched everyone,” said Afiya Lahens, a black parent whose daughter is in the general education track.

Then something remarkable happened. After years of discussion and community meetings, a mixed-race committee of parents and teachers voted to phase out the gifted and talented track for future students at PS 9, specifically to decrease racial and economic segregation.

New York City's education department agreed to follow the decision: Starting this fall, there will be no gifted track for the school’s incoming kindergartners. Instead, PS 9 will offer enrichment opportunities to more students based on their individual strengths and interests.

The move put PS 9 at the forefront of controversy surrounding racial integration in the nation’s largest school system – and one of its most segregated. It's raised questions about whether school systems can have both excellence and equity and whether integration efforts should come from parents or official intervention.

The controversies have been particularly acute in Brooklyn, where white and affluent families populate neighborhoods historically inhabited by black and Latino residents. Gentrification has displaced people of color by driving up rents and intensified racial stratification in classrooms.

Segregation:It's getting worse in schools, GAO says

Phasing out gifted and talented programs at PS 9 will test a controversial recommendation from a school diversity panel appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio to end such programs at all elementary schools in the city. The panel’s rationale: Gifted programs are biased and serve to segregate children along lines of race and class, in large part because admission to most programs is based on a screening exam parents can register their children to take, starting at age 4.

Wealthy New York families often spend thousands of dollars on test prep for their preschoolers because the number of gifted and talented seats is limited. In a system of about 1.1 million children, about 16,000 seats are available in city-run elementary schools. As a result, gifted programs tend to isolate affluent children, and the power and resources that follow them can result in fewer resources for the general population.

Across the country, schools are locked in intense debates about what to do about gifted and talented programs, largely because of racial disparities. Some districts have stopped tracking gifted students. Others move to diversify gifted programs by ensuring more disadvantaged students have a chance to be tested.

In New York City, radically overhauling gifted and talented programs has long been a political third rail, largely because the programs are popular with affluent parents whose children are enrolled. That's the demographic New York sought to court in the 1970s and '80s with gifted programs in the first place, lest those families, often with more involved parents and higher incomes for tax purposes, move to the suburbs in search of better schools, education researchers said.

“We got a lot of pushback” on the overhaul, said PS 9 parent Kirsten Cole, who is white. “I feel naive in saying this: It was more than I expected.”

New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has championed school integration since de Blasio appointed him in 2018. That energized advocates for diversity, but many grow impatient that neither leader has adopted the most radical recommendations to help all schools to reflect the diversity of the city. The chancellor and the mayor declined to phase out all gifted and talented programs or to prohibit schools from using achievement measures to screen children for admission.

Department of Education officials indicate they're more interested in supporting efforts that bubble up from individual communities. A spokeswoman told USA TODAY integration initiatives are not a “one-size-fits-all model."

The city has been under pressure to do something since a major report in 2014 spelled out how New York schools had become the most racially segregated in the country.

De Blasio floated scrapping admissions tests to the most elite high schools – often seen as the destination for gifted and talented students – where black and Hispanic students are underrepresented. That idea faced major opposition, especially from some Asian lawmakers and certain alumni. It's unlikely to go forward because it would require action from the state Legislature.

Then there’s the troubling fact that the move to eliminate gifted programs is opposed by some black and Latino parents, whose kids it's supposed to help. Some of those parents see elementary school gifted programs, as well as elite high schools, as the only way for their children to work hard and get ahead.

“The whole thing is a red herring,” said Ayanna Behin, a Brooklyn parent and president of the parent advisory group in the district that includes PS 9. Behin is black, and her children attend a different Brooklyn school that pursued another path to maintain integration: It changed its admissions policies to set aside more seats for low-income students.

“Students in the gifted and talented program make up a tiny percentage of the system, and yet talk about eliminating that program generates a huge amount of controversy,” Behin said. “What we really need to be focusing on is fixing the system for everybody.”

Gifted programs: Roots in segregation, debatable benefits

Some say fixing the system for everyone must start with how children are classified and expected to learn, which goes to the heart of the debate around gifted education.

In New York City, children who score in the top tier of the gifted and talented exam can compete for slots at citywide gifted schools and programs at traditional elementary schools.

In 2019, more than 32,000 students in kindergarten through third grade took the exam, and almost 8,000 scored high enough to qualify for a gifted program. That doesn't guarantee them a seat. Schools offer the limited number of seats in order of students' scores on the exam.

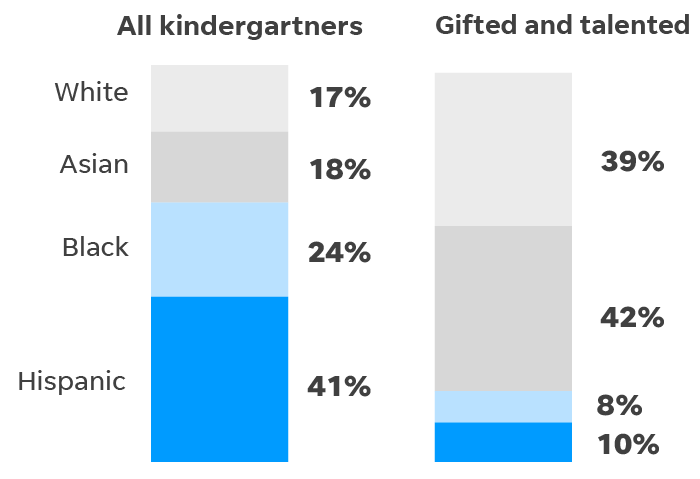

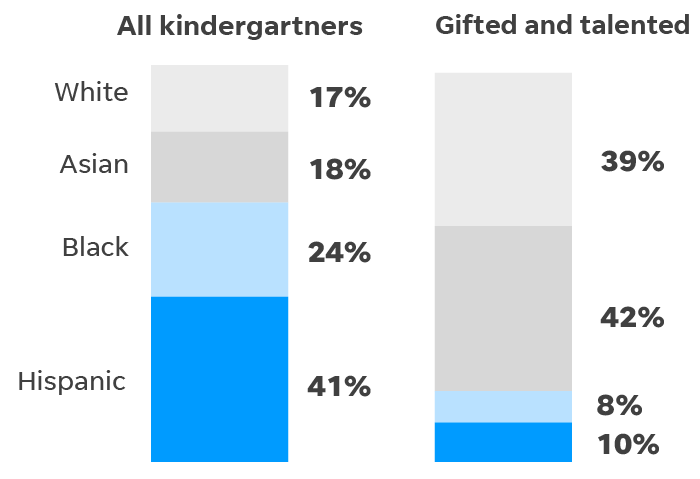

The odds are low for black and Latino students. They make up close to 70% of the district’s enrollment, but far fewer of them take the gifted test. Of all kindergartners in 2017-18 who passed the test and received an offer for gifted and talented, just 10% were Latino and 8% were black.

In contrast, 17% of New York kindergartners are white, but they made up 39% of kindergartners who received 2017-18 offers for gifted and talented seats. Eighteen percent of kindergartners are Asian, but they made up 42% of the gifted seats.

Racial disparity in New York City’s kindergarten classes and its gifted and talented programs

Those divides are not due to cognitive differences between races, but a function of access, resources and systemic bias against blacks and Latinos, education experts said.

Studies show nonblack teachers are less likely to recommend black students for gifted and talented programs. Another study showed that when parents and teachers nominated children, they missed many qualified students. When the large urban district in that study, Broward County Public Schools in Florida, switched to screening all children in second grade, more low-income and minority students were placed in gifted programs.

Because there's no federal standard for identifying giftedness, states and districts come up with their own definitions – which is one reason researchers don't have a clear answer on the benefits of gifted education.

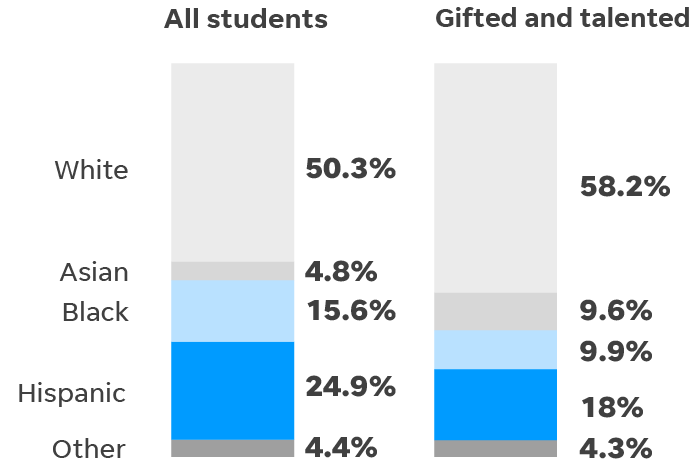

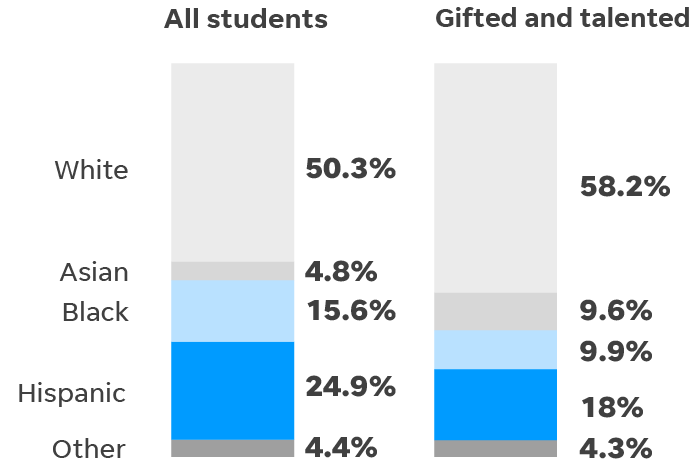

US racial disparity in gifted and talented programs from kindergarten to 12th grade

Some say highly talented children can reach their full potential only if they're educated alongside other high-achieving students. Some studies show pulling gifted kids out of regular classes to work together for part of the day increased the children’s achievement, critical thinking and creativity.

“It’s good for kids to be with their intellectual peers,” said David Lubinski, a psychology professor at Vanderbilt University and longtime expert on gifted education.

Other academics say the stratification caused by ambiguously defined talent produces damaging levels of segregation. When students of varying abilities work together, lower-performing students do better, research shows, without slowing the progress of average and high-achieving students.

“If you think that public schools should be leveling the playing field for all kids, then identifying children and ranking their potential based on who signed them up to take a test tends to reinforce the inequalities we see in society,” said Allison Roda, an assistant professor of education at Molloy College in New York, who wrote a book about gifted education and segregation in New York City.

The first major studies of gifted kids in America started in the 1920s and '30s when urban centers experienced an influx of immigrants, Roda said. Schools intentionally created different tracks to separate students by race, class and linguistic ability, she said.

In 1957, after the launch of the Soviet Union's Sputnik satellite, the United States ramped up math and science programs for talented students who could help the country compete in the “space race.” When schools navigated the civil rights movement in the '60s and '70s, gifted education remained a path where mostly white and wealthy students could be educated separately from their peers of color, Roda said.

For her book, Roda interviewed New York parents whose children tested into gifted programs.

“They admit that the admissions system is flawed, but they still kind of work it to their advantage,” she said.

The same things white people want for their children'

USA TODAY

NEW YORK – The holiday performances always gave it away.

Every December, as students at Public School 9 in Brooklyn stood to sing holiday songs while their parents looked on, one class would be made up of a lot of white students, followed by another class of almost all black students.

From the outside, the racial divide might seem curious as PS 9 is one of the most diverse elementary schools in Brooklyn: Out of about 940 students, 40% are black, 31% are white, 17% are Hispanic and 9% are Asian. But inside, many students spend their days learning in separate groups. The gifted and talented classes are attended by mostly white and Asian kids; the general education classes, mostly black students.

“It wasn’t obvious until you sat in the audience and watched everyone,” said Afiya Lahens, a black parent whose daughter is in the general education track.

Then something remarkable happened. After years of discussion and community meetings, a mixed-race committee of parents and teachers voted to phase out the gifted and talented track for future students at PS 9, specifically to decrease racial and economic segregation.

New York City's education department agreed to follow the decision: Starting this fall, there will be no gifted track for the school’s incoming kindergartners. Instead, PS 9 will offer enrichment opportunities to more students based on their individual strengths and interests.

The move put PS 9 at the forefront of controversy surrounding racial integration in the nation’s largest school system – and one of its most segregated. It's raised questions about whether school systems can have both excellence and equity and whether integration efforts should come from parents or official intervention.

The controversies have been particularly acute in Brooklyn, where white and affluent families populate neighborhoods historically inhabited by black and Latino residents. Gentrification has displaced people of color by driving up rents and intensified racial stratification in classrooms.

Segregation:It's getting worse in schools, GAO says

Phasing out gifted and talented programs at PS 9 will test a controversial recommendation from a school diversity panel appointed by Mayor Bill de Blasio to end such programs at all elementary schools in the city. The panel’s rationale: Gifted programs are biased and serve to segregate children along lines of race and class, in large part because admission to most programs is based on a screening exam parents can register their children to take, starting at age 4.

Wealthy New York families often spend thousands of dollars on test prep for their preschoolers because the number of gifted and talented seats is limited. In a system of about 1.1 million children, about 16,000 seats are available in city-run elementary schools. As a result, gifted programs tend to isolate affluent children, and the power and resources that follow them can result in fewer resources for the general population.

Across the country, schools are locked in intense debates about what to do about gifted and talented programs, largely because of racial disparities. Some districts have stopped tracking gifted students. Others move to diversify gifted programs by ensuring more disadvantaged students have a chance to be tested.

In New York City, radically overhauling gifted and talented programs has long been a political third rail, largely because the programs are popular with affluent parents whose children are enrolled. That's the demographic New York sought to court in the 1970s and '80s with gifted programs in the first place, lest those families, often with more involved parents and higher incomes for tax purposes, move to the suburbs in search of better schools, education researchers said.

“We got a lot of pushback” on the overhaul, said PS 9 parent Kirsten Cole, who is white. “I feel naive in saying this: It was more than I expected.”

New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza has championed school integration since de Blasio appointed him in 2018. That energized advocates for diversity, but many grow impatient that neither leader has adopted the most radical recommendations to help all schools to reflect the diversity of the city. The chancellor and the mayor declined to phase out all gifted and talented programs or to prohibit schools from using achievement measures to screen children for admission.

Department of Education officials indicate they're more interested in supporting efforts that bubble up from individual communities. A spokeswoman told USA TODAY integration initiatives are not a “one-size-fits-all model."

The city has been under pressure to do something since a major report in 2014 spelled out how New York schools had become the most racially segregated in the country.

De Blasio floated scrapping admissions tests to the most elite high schools – often seen as the destination for gifted and talented students – where black and Hispanic students are underrepresented. That idea faced major opposition, especially from some Asian lawmakers and certain alumni. It's unlikely to go forward because it would require action from the state Legislature.

Then there’s the troubling fact that the move to eliminate gifted programs is opposed by some black and Latino parents, whose kids it's supposed to help. Some of those parents see elementary school gifted programs, as well as elite high schools, as the only way for their children to work hard and get ahead.

“The whole thing is a red herring,” said Ayanna Behin, a Brooklyn parent and president of the parent advisory group in the district that includes PS 9. Behin is black, and her children attend a different Brooklyn school that pursued another path to maintain integration: It changed its admissions policies to set aside more seats for low-income students.

“Students in the gifted and talented program make up a tiny percentage of the system, and yet talk about eliminating that program generates a huge amount of controversy,” Behin said. “What we really need to be focusing on is fixing the system for everybody.”

Gifted programs: Roots in segregation, debatable benefits

Some say fixing the system for everyone must start with how children are classified and expected to learn, which goes to the heart of the debate around gifted education.

In New York City, children who score in the top tier of the gifted and talented exam can compete for slots at citywide gifted schools and programs at traditional elementary schools.

In 2019, more than 32,000 students in kindergarten through third grade took the exam, and almost 8,000 scored high enough to qualify for a gifted program. That doesn't guarantee them a seat. Schools offer the limited number of seats in order of students' scores on the exam.

The odds are low for black and Latino students. They make up close to 70% of the district’s enrollment, but far fewer of them take the gifted test. Of all kindergartners in 2017-18 who passed the test and received an offer for gifted and talented, just 10% were Latino and 8% were black.

In contrast, 17% of New York kindergartners are white, but they made up 39% of kindergartners who received 2017-18 offers for gifted and talented seats. Eighteen percent of kindergartners are Asian, but they made up 42% of the gifted seats.

Racial disparity in New York City’s kindergarten classes and its gifted and talented programs

Those divides are not due to cognitive differences between races, but a function of access, resources and systemic bias against blacks and Latinos, education experts said.

Studies show nonblack teachers are less likely to recommend black students for gifted and talented programs. Another study showed that when parents and teachers nominated children, they missed many qualified students. When the large urban district in that study, Broward County Public Schools in Florida, switched to screening all children in second grade, more low-income and minority students were placed in gifted programs.

Because there's no federal standard for identifying giftedness, states and districts come up with their own definitions – which is one reason researchers don't have a clear answer on the benefits of gifted education.

US racial disparity in gifted and talented programs from kindergarten to 12th grade

Some say highly talented children can reach their full potential only if they're educated alongside other high-achieving students. Some studies show pulling gifted kids out of regular classes to work together for part of the day increased the children’s achievement, critical thinking and creativity.

“It’s good for kids to be with their intellectual peers,” said David Lubinski, a psychology professor at Vanderbilt University and longtime expert on gifted education.

Other academics say the stratification caused by ambiguously defined talent produces damaging levels of segregation. When students of varying abilities work together, lower-performing students do better, research shows, without slowing the progress of average and high-achieving students.

“If you think that public schools should be leveling the playing field for all kids, then identifying children and ranking their potential based on who signed them up to take a test tends to reinforce the inequalities we see in society,” said Allison Roda, an assistant professor of education at Molloy College in New York, who wrote a book about gifted education and segregation in New York City.

The first major studies of gifted kids in America started in the 1920s and '30s when urban centers experienced an influx of immigrants, Roda said. Schools intentionally created different tracks to separate students by race, class and linguistic ability, she said.

In 1957, after the launch of the Soviet Union's Sputnik satellite, the United States ramped up math and science programs for talented students who could help the country compete in the “space race.” When schools navigated the civil rights movement in the '60s and '70s, gifted education remained a path where mostly white and wealthy students could be educated separately from their peers of color, Roda said.

For her book, Roda interviewed New York parents whose children tested into gifted programs.

“They admit that the admissions system is flawed, but they still kind of work it to their advantage,” she said.

The same things white people want for their children'