Whedon has moments of gravitas to balance out the camp. they only get highlighted when the editing room cuts all the serious moments out. Like various moments in Avengers And Avengers: AOU

Joss Whedon - Web Exclusive

By Tasha Robinson

Joss Whedon is a third-generation television scriptwriter, possibly the first one. As he tells the story, he never intended to follow in his father's footsteps: He started his career as a snobby film student who never watched television and intended to write movies, until he found out how much TV writing paid. Ultimately, he did both, working as a scriptwriter on

Roseanne and the TV series

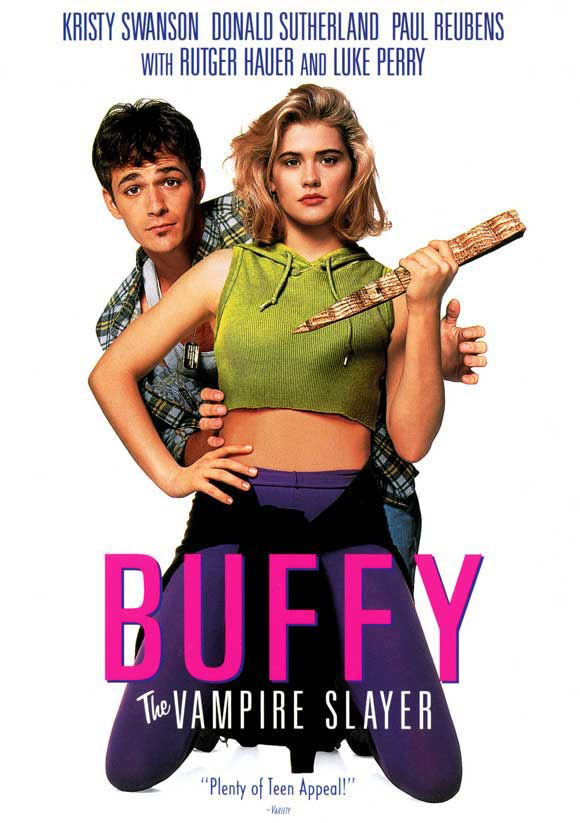

Parenthood before selling his script to the 1992

Buffy The Vampire Slayer movie. For several years, he was a film writer and a script doctor, doing uncredited touch-ups on

Twister, Speed, and

Waterworld, and writing drafts of projects such as

X-Men, Toy Story, Titan A.E., Disney's

Atlantis, and

Alien: Resurrection. But Whedon came into his own with the television incarnation of

Buffy, which has, over the past few years, grown from a cult classic into a cottage industry. As the original creator of the Buffy character, Whedon--now a writer, director, and executive producer of the

Buffy The Vampire Slayer TV show--has a hand in virtually all of its spinoffs, including the WB series

Angel, a line of comic-book tie-ins distributed by Dark Horse, and an upcoming animated series and BBC TV show. Whedon recently spoke to

The Onion A.V. Club about the

Buffy phenomenon, his bitterness over his movie career, and the fans who share in his worship of his creations.

The Onion: So, how are you bringing Buffy back? [The character died at the end of this past season. —ed.]

Joss Whedon: Aw, I'm not supposed to tell.

O: I'm teasing. I know you get that a lot.

JW: Yeah, it's the first thing everybody asks, including my developers. And the answer is, I can't say, because that's why you watch the show. The one thing I can say is, I think we earn it. There's no Patrick Duffy in the shower, there's no alternate-universe Buffy. It's not going to be neat. Bringing her back is difficult, and the consequences are fairly intense. It's not like we don't take these death-things seriously. But exactly how she comes back, I can't reveal.

O: When your actors get questions like that in interviews, they always seem to answer with horrific threats: "I can't tell, Joss will rip out my tongue and feed it to wolves," and so forth. Do they actually get these threats from you?

JW: I'm a very gentle man, not unlike Gandhi. I don't ever threaten them. There is, sort of hanging over their head, the thing that I could kill them at any moment. But that's really just if they annoy me. They know that I'm very secretive about plot twists and whatnot, because I think it's better for the show. But anybody with a computer can find out what's going to happen, apparently even before I know. So my wish for secrecy is sort of pathetic. But they're all on board. They don't want to give it away, and a lot of times, they just don't know.

O: How closely were you involved with the making of the

Buffy movie?

JW: I had major involvement. I was there almost all the way through shooting. I pretty much eventually threw up my hands because I could not be around Donald Sutherland any longer. It didn't turn out to be the movie that I had written. They never do, but that was my first lesson in that. Not that the movie is without merit, but I just watched a lot of stupid wannabe-star behavior and a director with a different vision than mine—which was her right, it was her movie—but it was still frustrating. Eventually, I was like, "I need to be away from here."

O: Was it a personality conflict between you and Sutherland, or was he just not what you'd envisioned in that role?

JW: No, no, he was just a prick. The thing is, people always make fun of Rutger Hauer [for his

Buffy role]. Even though he was big and silly and looked kind of goofy in the movie, I have to give him credit, because he was there. He was into it. Whereas Donald was just... He would rewrite all his dialogue, and the director would let him. He can't write—he's not a writer—so the dialogue would not make sense. And he had a very bad attitude. He was incredibly rude to the director, he was rude to everyone around him, he was just a real pain. And to see him destroying my stuff... Some people didn't notice. Some people liked him in the movie. Because he's Donald Sutherland. He's a great actor. He can read the phone book, and I'm interested. But the thing is, he acts well enough that you didn't notice, with his little rewrites, and his little ideas about what his character should do, that he was actually destroying the movie more than Rutger was. So I got out of there. I had to run away.

O: What was Paul Reubens like? He seems to be the actor people remember most from the movie.

JW: [Adopts weepy, awed voice.] He is a god that walks among us. He is one of the sweetest, most professional and delightful people I've ever worked with. [Normal voice.] He was my beacon of hope in that whole experience, that he was such a good guy, and so got it. I mean, most of the people were sweet. Most of them were actively out there trying... They were good people. Paul was a delight to be around, trying to make it better. He actually said to me, "I'm a little worried about this line, and I want to change it. I realize that it'll change this other thing, so if that's a problem..." I'm like, "Did I just hear an actor say that?"

O: How early on did it occur to you to re-do

Buffy the way you'd originally intended?

JW: You know, it wasn't really my idea. After the première of the movie, my wife said, "You know, honey, maybe a few years from now, you'll get to make it again, the way you want to make it!" [Broad, condescending voice.] "Ha ha ha, you little naïve fool. It doesn't work that way. That'll never happen." And then it was three years later, and Gail Berman actually had the idea. Sandollar [Television] had the property, and Gail thought it would make a good TV series. They called me up out of contractual obligation: "Call the writer, have him pass." And I was like, "Well, that sounds cool." So, to my agent's surprise and chagrin, I said, "Yeah, I could do that. I think I get it. It could be a high-school horror movie. It'd be a metaphor for how lousy my high-school years were." So I hadn't had the original idea, I just developed it.

O: You joke a lot in interviews about how you wanted to write horror because you experienced so much of it in high school. Did you have an unusually bad high-school experience, or was it just the usual teen traumas?

JW: I think it's not inaccurate to say that I had a perfectly happy childhood during which I was very unhappy. It was nothing worse than anybody else. I could not get a date to save my life, but my last three years of high school were at a boys' school, so I wasn't actually looking that hard. I was not popular in school, and I was definitely not a ladies' man. And I had a very painful adolescence, because it was all very strange to me. It wasn't like I got beat up, but the humiliation and isolation, and the existential "God, I exist, and nobody cares" of being a teenager were extremely pronounced for me. I don't have horror stories. I mean, I have a few horror stories about attempting to court a girl, which would make people laugh, but it's not like I think I had it worse than other people. But that's sort of the point of

Buffy, that I'm talking about the stuff everybody goes through. Nobody gets out of here without some trauma.

O: How much of your writing made it into the final versions of

Twister and

Speed?

JW: Most of the dialogue in

Speed is mine, and a bunch of the characters. That was actually pretty much a good experience. I have quibbles. I also have the only poster left with my name still on it. Getting arbitrated off the credits was un-fun. But

Speed has a bunch. And

Twister, less. In

Twister, there are things that worked and things that weren't the way I'd intended them. Whereas

Speed came out closer to what I'd been trying to do. I think of

Speed as one of the few movies I've made that I actually like.

O: What about

Waterworld?

JW: [Laughs.]

Waterworld. I refer to myself as the world's highest-paid stenographer. This is a situation I've been in a bunch of times. By the way, I'm very bitter, is that okay? I mean, people ask me, "What's the worst job you ever had?" "I once was a writer in Hollywood..." Talk about taking the glow off of movies. I've had almost nothing but bad experiences.

Waterworld was a good idea, and the script was the classic, "They have a good idea, then they write a generic script and don't really care about the idea." When I was brought in, there was no water in the last 40 pages of the script. It all took place on land, or on a ship, or whatever. I'm like, "Isn't the cool thing about this guy that he has gills?" And no one was listening. I was there basically taking notes from Costner, who was very nice, fine to work with, but he was not a writer. And he had written a bunch of stuff that they wouldn't let their staff touch. So I was supposed to be there for a week, and I was there for seven weeks, and I accomplished nothing. I wrote a few puns, and a few scenes that I can't even sit through because they came out so bad. It was the same situation with

X-Men. They said, "Come in and punch up the big climax, the third act, and if you can, make it cheaper." That was the mandate on both movies, and my response to both movies was, "The problem with the third act is the first two acts." But, again, no one was paying attention.

X-Men was very interesting in that, by that time, I actually had a reputation in television. I was actually somebody. People stopped thinking I was John Sweden on the phone. And then, in

X-Men, not only did they throw out my script and never tell me about it; they actually invited me to the read-through, having thrown out my entire draft without telling me. I was like, "Oh, that's right! This is the movies! The writer is shyt in the movies!" I'll never understand that. I have one line left in that movie. Actually, there are a couple of lines left in that are out of context and make no sense, or are delivered so badly, so terribly... There's one line that's left the way I wrote it.

O: Which is?

JW: "'It's me.' 'Prove it.' 'You're a dikk.'" Hey, it got a laugh.

O: It's funny that the only lines I really remember from that movie are that one and Storm's toad comment.

JW: Okay, which was also mine, and that's the interesting thing. Everybody remembers that as the worst line ever written, but the thing about that is, it was supposed to be delivered as completely offhand. [Adopts casual, bored tone.] "You know what happens when a toad gets hit by lightning?" Then, after he gets electrocuted, "Ahhh, pretty much the same thing that happens to anything else." But Halle Berry said it like she was Desdemona. [Strident, ringing voice.] "The same thing that happens to everything eeelse!" That's the thing that makes you go crazy. At least "You're a dikk" got delivered right. The worst thing about these things is that, when the actors say it wrong, it makes the writer look stupid. People assume that the line... I listened to half the dialogue in

Alien 4, and I'm like, "That's idiotic," because of the way it was said. And nobody knows that. Nobody ever gets that. They say, "That was a stupid script," which is the worst pain in the world. I have a great long boring story about that, but I can tell you the very short version. In

Alien 4, the director changed something so that it didn't make any sense. He wanted someone to go and get a gun and get killed by the alien, so I wrote that in and tried to make it work, but he directed it in a way that it made no sense whatsoever. And I was sitting there in the editing room, trying to come up with looplines to explain what's going on, to make the scene make sense, and I asked the director, "Can you just explain to me why he's doing this? Why is he going for this gun?" And the editor, who was French, turned to me and said, with a little leer on his face, [adopts gravelly, smarmy, French-accented voice] "Because eet's een the screept." And I actually went and dented the bathroom stall with my puddly little fist. I have never been angrier. But it's the classic, "When something goes wrong, you assume the writer's a dork." And that's painful.

O: Have you done any other uncredited script work?

JW: Actually, my first gig ever was writing looplines for a movie that had already been made. You know, writing lines over somebody's back to explain something, to help make a connection, to add a joke, or to just add babble because the people are in frame and should be saying something. We're constantly saving something that doesn't work, or trying to, with lines behind people's backs. It's almost like adding narration, but cheaper. I did looplines for

The Getaway, the Alec Baldwin/Kim Basinger version. If you look carefully at

The Getaway, you'll see that when people's backs are turned, or their heads are slightly out of frame, the whole movie has a certain edge to it. I also did a couple of days of looplines and punch-ups for

The Quick And The Dead, just to meet Sam Raimi.

O: I attended your Q&A session at a comics convention last year, and many of the people who got up to ask questions were nearly in tears over the chance to get to talk to you. Some of them could barely speak, and others couldn't stop gushing about you, and about

Buffy. How do you deal with that kind of emotional intensity?

JW: It's about the show, and I feel the same way about it. I get the same way. It's not like being a rock star. It doesn't feel like they're reacting to me. It's really sweet when people react like that, and I love the praise, but to me, what they're getting emotional about is the show. And that's the best feeling in the world. There's nothing creepy about it. I feel like there's a religion in narrative, and I feel the same way they do. I feel like we're both paying homage to something else; they're not paying homage to me.

shyt seems like a no brainer to me but cool

extensive world building of Gotham

..I just want to make sure it's done right. The Bat Family deserves to be done Justice on screen.

..I just want to make sure it's done right. The Bat Family deserves to be done Justice on screen...I just want to make sure it's done right. The Bat Family deserves to be done Justice on screen.