{continued}

One of the benefits of Twitter was how it created a sense of community for scientists, particularly for those from under-represented groups. It gave a voice to female researchers about issues such as harassment and unequal pay, and served as an organizing point for scientists of colour to speak out against inequity. Scientists could discuss suspicions of research fraud, often anonymously, and because many journalists used the platform, people who might otherwise have been ignored sometimes got results. Dorador says that Twitter helped to raise awareness and accountability for concepts such as scientific colonialism and gender and sexual diversity.

The dynamics of networks on Twitter were also of great interest to researchers. Unlike many other social networks, Twitter had, until recently, an open application programming interface (API) that allowed scientists to explore how people interacted with the platform and with one another, leading to studies on how users were discussing climate change, how people with autism were using it to be heard and the patterns of account suspensions relating to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, among other things.

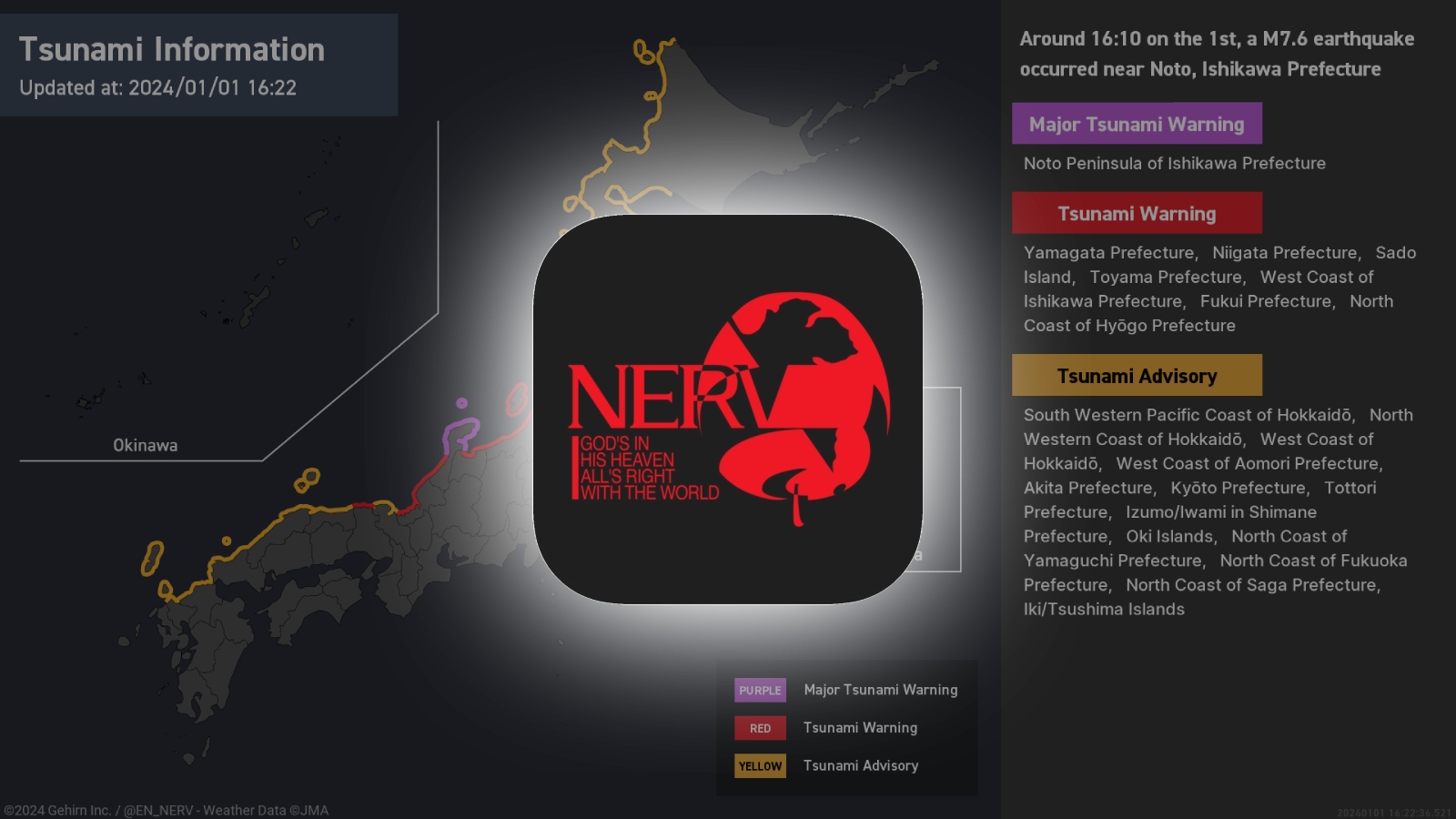

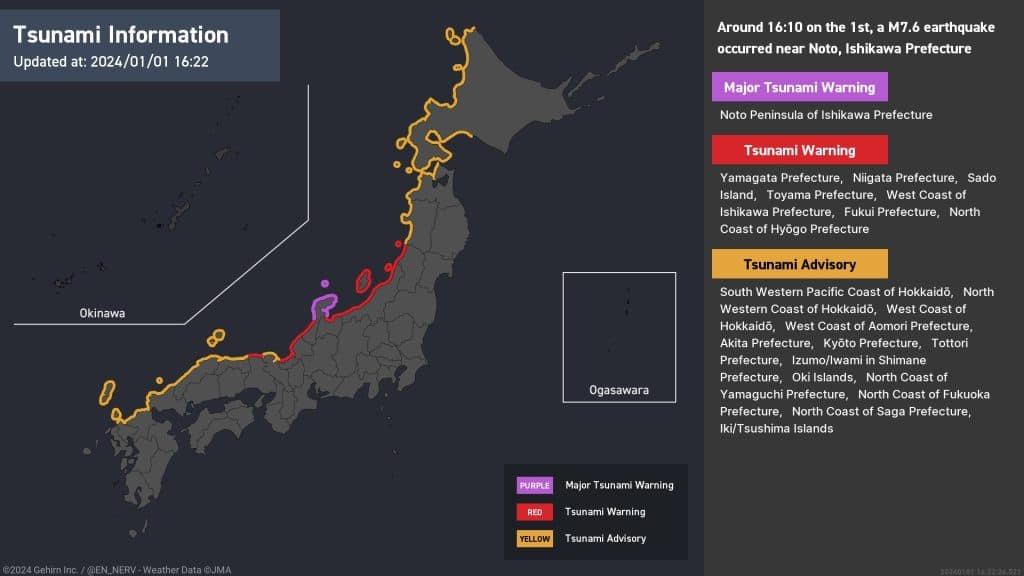

In February, the platform announced that it would close the free access to its API, although the change didn’t come into effect until the end of June. Since then, research on misinformation, disaster responses and social dynamics on the Internet has been halted or hampered. Costas and Dudek, for example, don’t have free access to new data to further their research on how users engage with science and create communities. They now have to rely on information from previous analyses. “There’s still so many things that I would like to do,” Dudek says.

He and Costas also worry that these changes will halt their collaborations with other scientists in the field. “The way academics could access Twitter also created a nice framework for sharing data,” Costas says. Now, someone who pays to access X data will not be able to share it with others to do complementary research or replicate findings unless the other team also pays, he says.

Jarochowska suggests that scientists focus on organizing webinars, building networks to share data and methods, and finding original ways to stand out. In some ways, she’s glad to have put Twitter behind her. “If you appear with your scientific contents between videos of cats,” she says, “it’s not a particularly good medium for promoting yourself professionally, anyway”.

Mark Carrigan, a digital sociologist at the Manchester Institute for Education, UK, argues that the idea that Twitter helped democratize academia “was a bit simplistic” because social media created a space where academic celebrities thrived. Even when it helped to diversify science, he says, it did so through the reinforcement of the same kinds of hierarchy. “Rewards flow to those who are known, valued and heard while those who are unknown, unvalued and unheard struggle to increase their standing,” he wrote in a 2019 article.

He now emphasizes that conventional networking organizations should be eyeing this as an opportunity. Professional associations, societies, study groups, research networks, research centres and laboratories have a responsibility to curate and support their own networks, he says. “I’m 99% convinced that Twitter, as we know it, is dead, and the sooner academics accept that, the better, in terms of finding solutions to these problems.”

One of the benefits of Twitter was how it created a sense of community for scientists, particularly for those from under-represented groups. It gave a voice to female researchers about issues such as harassment and unequal pay, and served as an organizing point for scientists of colour to speak out against inequity. Scientists could discuss suspicions of research fraud, often anonymously, and because many journalists used the platform, people who might otherwise have been ignored sometimes got results. Dorador says that Twitter helped to raise awareness and accountability for concepts such as scientific colonialism and gender and sexual diversity.

The dynamics of networks on Twitter were also of great interest to researchers. Unlike many other social networks, Twitter had, until recently, an open application programming interface (API) that allowed scientists to explore how people interacted with the platform and with one another, leading to studies on how users were discussing climate change, how people with autism were using it to be heard and the patterns of account suspensions relating to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, among other things.

In February, the platform announced that it would close the free access to its API, although the change didn’t come into effect until the end of June. Since then, research on misinformation, disaster responses and social dynamics on the Internet has been halted or hampered. Costas and Dudek, for example, don’t have free access to new data to further their research on how users engage with science and create communities. They now have to rely on information from previous analyses. “There’s still so many things that I would like to do,” Dudek says.

He and Costas also worry that these changes will halt their collaborations with other scientists in the field. “The way academics could access Twitter also created a nice framework for sharing data,” Costas says. Now, someone who pays to access X data will not be able to share it with others to do complementary research or replicate findings unless the other team also pays, he says.

What happens next?

Whether X will manage to regain its attractiveness to scientists, or whether some other social-media platform will grow into its space, is unclear. Mewburn doesn’t see the loss of Twitter as a fatal blow to the scientific enterprise. “I don’t think science has become overly dependent on social media,” she says. Scientists might find it more difficult to network and build their careers, especially if they don’t have the money to go to conferences, but she expects that people will come up with creative new ideas.Jarochowska suggests that scientists focus on organizing webinars, building networks to share data and methods, and finding original ways to stand out. In some ways, she’s glad to have put Twitter behind her. “If you appear with your scientific contents between videos of cats,” she says, “it’s not a particularly good medium for promoting yourself professionally, anyway”.

Mark Carrigan, a digital sociologist at the Manchester Institute for Education, UK, argues that the idea that Twitter helped democratize academia “was a bit simplistic” because social media created a space where academic celebrities thrived. Even when it helped to diversify science, he says, it did so through the reinforcement of the same kinds of hierarchy. “Rewards flow to those who are known, valued and heard while those who are unknown, unvalued and unheard struggle to increase their standing,” he wrote in a 2019 article.

He now emphasizes that conventional networking organizations should be eyeing this as an opportunity. Professional associations, societies, study groups, research networks, research centres and laboratories have a responsibility to curate and support their own networks, he says. “I’m 99% convinced that Twitter, as we know it, is dead, and the sooner academics accept that, the better, in terms of finding solutions to these problems.”

twitter / X is toast...

twitter / X is toast...

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73238317/2117494777.0.jpg)