xoxodede

Superstar

Good for them. I know Tiff - I am glad she went back home - and doing well.

Black Americans leave USA to escape racism, build lives abroad

Anthony Baggette knew the precise moment he had to get out: He was driving by a convenience store in Cincinnati when a police officer pulled him over. There had been a robbery. He fit the description given by the store's clerk: a Black man.

Okunini Ọbádélé Kambon knew: He was arrested in Chicago and accused by police of concealing a loaded gun under a seat in his car. He did have a gun, but it was not loaded. He used it in his role teaching at an outdoor skills camp for inner-city kids. Kambon had a license. The gun was kept safely in the car's trunk.

Tiffanie Drayton knew: Her family kept getting priced out of gentrifying neighborhoods in New Jersey. She said they were destined to be forever displaced in the USA. Then Trayvon Martin was shot and killed after buying a bag of Skittles and a can of iced tea.

Tamir Rice would've been 18: Black teens make their mark in Tamir Rice’s America

Baggette lives in Germany, Drayton in Trinidad and Tobago, Kambon in Ghana.

All three are part of a small cultural cohort: Black emigres who said they felt cornered and powerless in the face of persistent racism, police brutality and economic struggles in the USA and chose to settle and pursue their American-born dreams abroad.

No official statistics cover these international transplants.

In Ghana, where Kambon is involved in a program that encourages descendants of the African diaspora to return to a nation where centuries earlier their ancestors were forced onto slave ships, he said he is one of "several thousand." Kambon rejects descriptors such as "Black American" or "African American" that identify him with the USA.

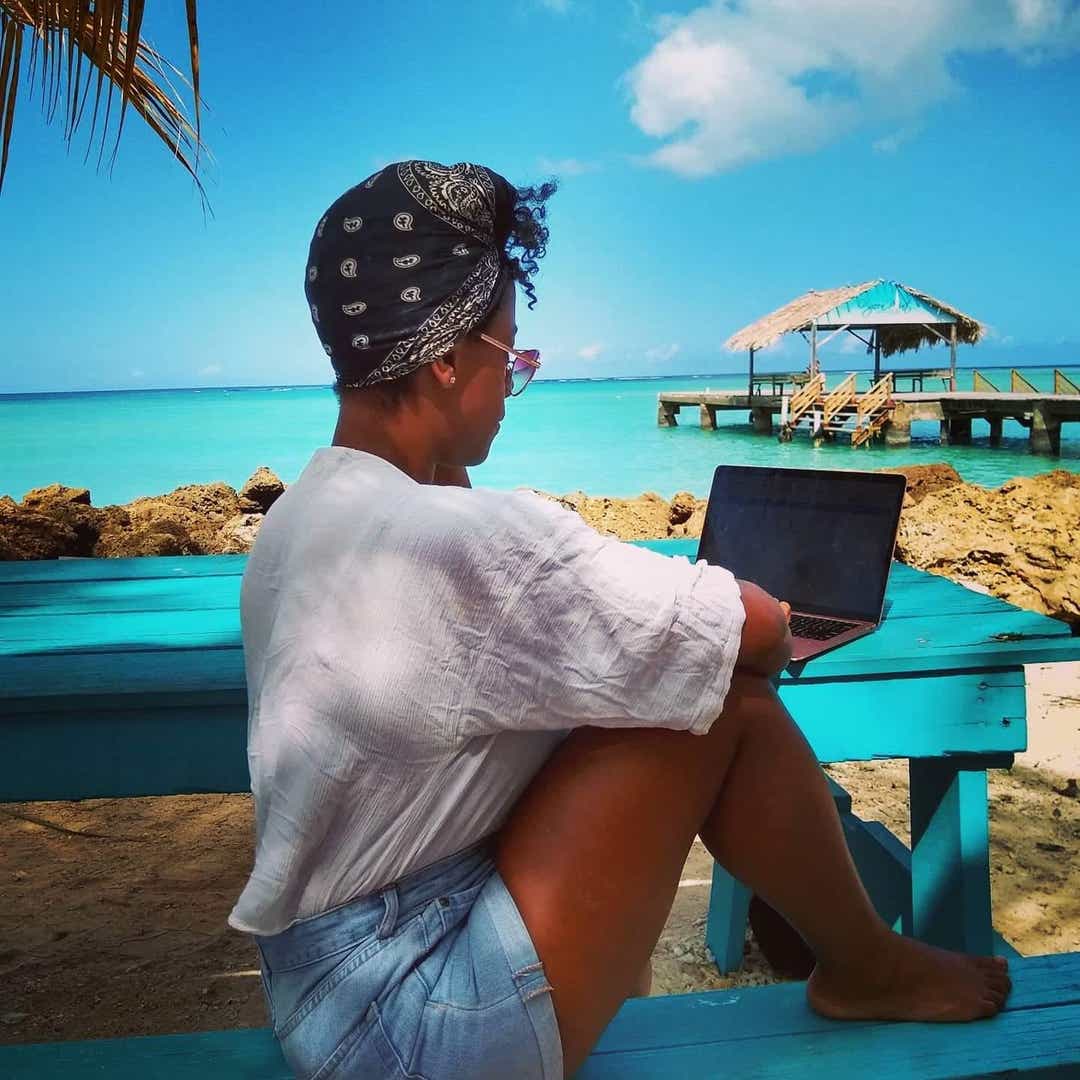

Tiffanie Drayton works on Pigeon Point beach, Trinidad and Tobago, in January.

Tiffanie Drayton

In Trinidad and Tobago, where Drayton works in her home office, which has a view of the ocean and hummingbirds frolicking above the pool, there are at least four: Drayton, her mother, sister and her sister's boyfriend. There are probably more.

About 120,000 Americans live in Germany, home to about 1 million people of African descent. For historical reasons, Germany's census does not use race as a category, so it is not possible to calculate how many hail from the USA.

"There's a lot of institutional racism in Germany," said Baggette, 68, who has lived in Berlin for more than 30 years and said he still feels conflicted about his move.

He described the fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, as a time when neo-Nazis and skinheads would "throw Black people off of the S-Bahn," the city's subway system.

"But I still felt, and feel, better off here – safer," he said.

'I don't have to think of myself as a Black woman'

In interviews with more than a dozen expatriate Black Americans spread out across the globe from the Caribbean to West Africa, it became clear that for some, the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis provided fresh evidence that living outside the USA can be an exercise in self-preservation.

A study in 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences found Black men were about 2.5 times more likely than white men to be killed by police. An analysis this year by Nature Human Behavior of 100 million traffic stops conducted across the country determined that Black people were far more likely to be pulled over by police than whites, but that difference narrowed significantly at night, when it is harder to see dark skin. Black Americans face a far higher risk of being arrested for petty crimes. They account for a third of the prison population but just 13% of the overall population, according to Pew Research, a nonpartisan "fact tank."

12 charts, 1 big problem: How racial disparities persist across wealth, health, education and beyond

Drayton, 28, is writing a book about fleeing from racism in America. She said one of the starkest illustrations of how her life has changed since moving to Trinidad and Tobago in 2013 is how she feels comfortable driving her kids around the block to get them to sleep each night without being worried about what happens if she is pulled over by police.

"In America, your hands are shaking. You're worried about what to say. You're worried about whether you have the right ID. You're just so worried all the time," she said of the interactions her friends experience regularly with American police officers.

For other Black Americans who chose what amounts to a form of foreign exile, Floyd's death and the ensuing protests confirmed that leaving may not mean a life free from racism and police brutality, but it at least feels somewhat more within reach.

Sienna Brown, fourth from left, and other Black American expatriates go on an outing near Valencia, Spain, in 2018.

Tanya Weekes

"It wasn't until I had left the USA to experience Spain that I really got a sense of what freedom looks like. I was able to be 100% myself without having to worry about safety and without needing to have too much of a complex identity," said Brooklyn, New York, native Sienna Brown, 28, who lives near Valencia on the Mediterranean Sea. Brown founded a company that helps Black American women emigrate to Spain.

She said Spain isn't racism-free and isn't that diverse, but she has experienced it as a welcoming place where people are willing to be educated about their prejudices.

Lakeshia Ford moved to Ghana full-time after visiting in 2008 as part of a study-abroad year in college.

"Here I don't have to think of myself as a Black woman and everything that comes with that," said Ford, 32, who grew up in New Jersey and runs her own communication firm in Accra, Ghana's capital. "Here I am just a woman."

"Here I am just a woman," says Lakeshia Ford in Accra, Ghana.

Nii Okai Djarbeng

She said that although racism in the USA contributed to the decision, her move to Ghana was not a direct reaction to prejudice. She was equally intrigued by Ghanaian culture and what she saw as a growing economic success story rarely portrayed in the West, where Africa for many is synonymous with disease, poverty and conflict.

"When I got here, I remember thinking: There's wealthy Black people here. No one tells you that. I was really pissed off about it. I was also really intrigued," she said.

Ford said that since Floyd's death in May, she has received several emails a day from Black Americans asking how they, too, can make a new life outside the USA.

"Come home, build a life in Ghana. You do not have to stay where you are not wanted forever. You have a choice, and Africa is waiting for you," Barbara Oteng Gyasi, Ghana's tourism minister, said during a ceremony last month marking Floyd's death.

'In Russia, I felt for the first time like a full human being'

Black Americans, like expatriates of all races and ethnicities, leave the USA temporarily or permanently for different reasons: in search of a better quality of life, for work opportunities, to marry or retire abroad, for tax reasons, for adventure.

This year, Essence, a Black fashion, entertainment and lifestyle magazine, published a list of Black travel influencers who "trek to faraway and sexy places," from "the pyramids of Giza" to "the souks of Dubai" while "we sit at our desks watching."

Kimberly Springer, a New York-based writer and researcher who spent almost a decade in the United Kingdom, where she taught American studies at King's College London, said that although "Black people have always traveled," and "we've gone places willingly or unwillingly," often this travel is connected in some way to a search for an experience that is not tainted by the myriad ways Black Americans encounter discrimination in the USA.

"In America, I feel hyper-visible in ways I didn't when I lived in the U.K.," said Springer, 50, noting that although racial inequalities in the U.K., like in the USA, are deep and pervasive, they are connected to a history and tradition – in the U.K.'s case, its former empire – that she doesn't share. As a foreigner, despite being a Black American foreigner, Springer said, she was afforded a certain amount of insulation from British racism, even though studies show the British justice system disproportionately penalizes Black people.

Fact check: Ghana is not offering money, land to lure Black Americans

"Our racism isn't as lethal as yours," said Gary Younge, a professor of sociology at Manchester University in England. Younge, 51, who is Black, spent more than a decade as The Guardian newspaper's U.S. correspondent.

"In Britain, I don't generally walk around thinking I might get killed, whereas in America, in some places, that's not always the case," he said.

Younge attributed this disparity to the availability in the USA of guns.

Asked whether Black people should confront racism at home, rather than leave, he said, "Why shouldn't they just live? If a white person leaves America and goes somewhere for work or better opportunities, no one would say to them they need to stay and fight for racial equality. Black people have a double burden of being discriminated against and having to stick around."

Black Americans have been trying to escape American racism – from segregation to heinous organized violence, such as lynchings – for generations.

There are examples among America's Black intellectuals, artists and prominent civil rights activists.

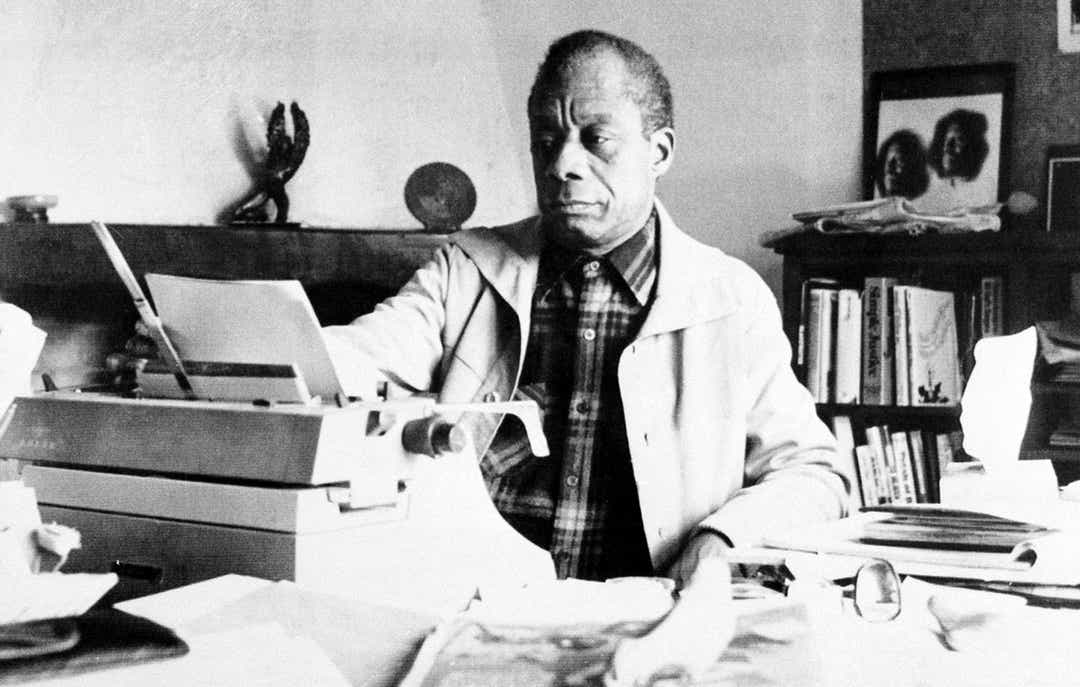

American novelist James Baldwin stayed in St. Paul de Vence in southern France in 1983.

AP

Writers James Baldwin and Richard Wright and entertainer Josephine Baker relocated to Paris. Wright and Baker died in France's capital. Poet Langston Hughes was part of an expatriate community in London. Jazz and blues singer Nina Simone decided to see out her days in France, and after she stopped performing, she never returned to what she called the "United Snakes of America." Simone also lived in Liberia, Barbados, Belgium, the U.K., the Netherlands and Switzerland. When she died in 2003, her ashes, at her request, were scattered across several African countries.

"I left this country for one reason only. One reason. I didn’t care where I’d go. I might’ve gone to Hong Kong, I might’ve gone to Timbuktu, I ended up in Paris with $40 in my pocket with the theory that nothing worse would happen to me there than had already happened to me here," Baldwin said in 1968 on "The dikk Cavett Show."

A decade prior, actor and singer Paul Robeson, famed for his deep baritone voice, said before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, "In Russia, I felt for the first time like a full human being. No color prejudice like in Mississippi, no color prejudice like in Washington. It was the first time I felt like a human being."

More recently, Yasiin Bey, an American rapper-actor better known by his stage name Mos Def, moved to South Africa because he was fed up with inequality and racism.

American musician Mos Def, right, leaves the Bellville magistrateís court in Bellville, South Africa, on Thursday. Mos Def a.k.a. Yasiin Bey, appeared on alleged charges for contravening immigrations laws in South Africa, the case was postponed till May 12, 2016.

Schalk van Zuydam, AP

"For a guy like me, with five or six generations from the same town in America, to leave America, things gotta be not so good with America," Bey said in 2013 as he prepared to leave the USA for Cape Town. He was thrown out of South Africa in 2016 for violating its immigration laws. He was detained after trying to leave the country on a "World Passport," which has no legal status. According to his lawyer, Bey did not want to use his American passport for political reasons.

That same year, as the U.K. voted to leave the European Union and President Donald Trump was elected, there was an uptick in people searching the internet for the term "Blaxit," according to Springer. If the U.K. could withdraw from the EU – "Brexit" – could Black people, disheartened by racial violence, leave the USA?

"I try not to use the phrase 'I can't breathe' too lightly," Springer said, referring to the words that became a rallying cry for police brutality protesters and were the last words of Floyd and Eric Garner, a Black man killed in police custody in 2014.

"But I think there is a way in which this country is, in its history and its failure to recognize it and reckon with it honestly, is suffocating," she said. "I really don't blame anyone thinks I can't take this country anymore, I'm leaving, and I'm just not coming back."