I approach this different than previous beefs. W.E.B. DuBois been a hero since my youth, and so Booker T. Washington had to be the bad guy. Now that I know better I see that life is more complex than that, so I tried to endow this beef with the respect for both legends that they deserve.

So this gonna be long.

Tale of the Tape

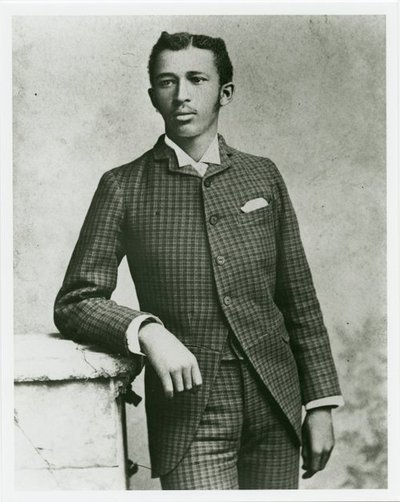

Booker T. Washington was born into slavery in 1856 and never knew his daddy. In 1865 he and his mama got the hell out of the South for West Virginia. Little Booker T desperately wanted to learn but opportunities for black folk weren't shyt, so he worked the salt furnaces and coal mines.

After seven years of that shyt he heard about Hampton and decided he would do anything to get there. Penniless at 16, Booker T left home and trekked 500 miles, sleeping under wooden sidewalks and hustling just to make it. Arriving weeks later, he proved his worth as a janitor and was allowed to stay on a work-study basis. He eventually became an instructor there, so beloved that its president once said,

"If Hampton had trained no other student in the seven years of its existence, the one now coming to the platform would justify all the costs and the sacrifices entailed by its founders.”

When some White folk wanted a White man to start a school for Black people in Alabama, General Armstrong sent them 25yo Booker T instead. He told those fools that Booker T was the finest student he'd ever had and no White man would be able to do it better. Booker T worked with his students to build the Tuskegee Institute from scratch, putting up the buildings, running the grounds and hustling the funding themselves, until they were training thousands of Black persons in academics and work skills.

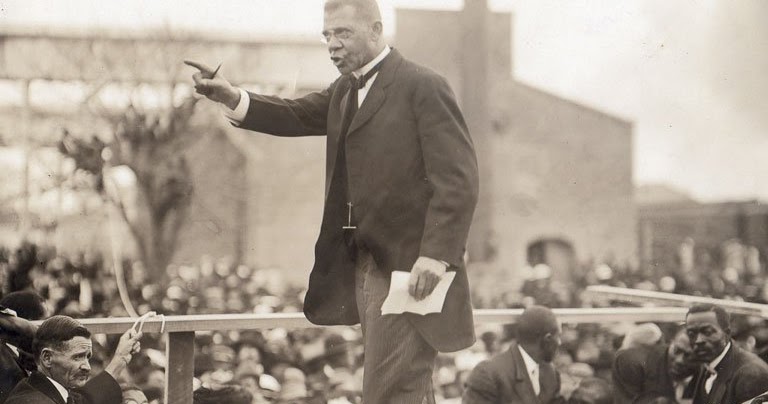

At Tuskegee Booker T had to play three games at once – convince Southern Whites that educated Black people were an asset, convince Northern Whites that funding Black education was worthwhile, and convince Black folk that education and vocational training would be the key to their own self-sufficiency. By all accounts he was a master politician, and soon had a huge following.

If there was one thing Booker T wanted to fight for, it was for Black men to have access to the training that would allow them to make an honest living.

W.E.B. DuBois might as well have been from a different planet. Born in 1868 in a 99% White town in Massachusetts to a free Black mama who hadn't known slavery for generations, he had the support of his teachers, becoming not only the first Black man to graduate from the high school but also the valedictorian. His daddy left when he was young and his mama died when he was 16, but W.E.B.'s childhood church raised the funds for him to attend college at Fisk in Tennessee, where he first encountered Jim Crow racism in a fuller form. From there he went on to Harvard and became the first Black man to earn a Harvard Ph.D.

His daddy left when he was young and his mama died when he was 16, but W.E.B.'s childhood church raised the funds for him to attend college at Fisk in Tennessee, where he first encountered Jim Crow racism in a fuller form. From there he went on to Harvard and became the first Black man to earn a Harvard Ph.D.

After graduation W.E.B. wrote to Booker T about working at Tuskegee, but Booker T's offer came too late and W.E.B agreed to teach at Wilberforce U instead. Soon he left and spent a year in Philly to make the first-ever case study of a Black community in the USA.

If there was one thing W.E.B. wanted to fight for, it was for a Black men to have the rights to reach their full potential in American society.

So this gonna be long.

Tale of the Tape

Booker T. Washington was born into slavery in 1856 and never knew his daddy. In 1865 he and his mama got the hell out of the South for West Virginia. Little Booker T desperately wanted to learn but opportunities for black folk weren't shyt, so he worked the salt furnaces and coal mines.

After seven years of that shyt he heard about Hampton and decided he would do anything to get there. Penniless at 16, Booker T left home and trekked 500 miles, sleeping under wooden sidewalks and hustling just to make it. Arriving weeks later, he proved his worth as a janitor and was allowed to stay on a work-study basis. He eventually became an instructor there, so beloved that its president once said,

"If Hampton had trained no other student in the seven years of its existence, the one now coming to the platform would justify all the costs and the sacrifices entailed by its founders.”

When some White folk wanted a White man to start a school for Black people in Alabama, General Armstrong sent them 25yo Booker T instead. He told those fools that Booker T was the finest student he'd ever had and no White man would be able to do it better. Booker T worked with his students to build the Tuskegee Institute from scratch, putting up the buildings, running the grounds and hustling the funding themselves, until they were training thousands of Black persons in academics and work skills.

At Tuskegee Booker T had to play three games at once – convince Southern Whites that educated Black people were an asset, convince Northern Whites that funding Black education was worthwhile, and convince Black folk that education and vocational training would be the key to their own self-sufficiency. By all accounts he was a master politician, and soon had a huge following.

If there was one thing Booker T wanted to fight for, it was for Black men to have access to the training that would allow them to make an honest living.

At Hampton I found the opportunity—in the way of buildings, teachers, and industries provided by the generous—to get training in the classroom and by practical touch with industrial life, to learn thrift, economy, and push. I was surrounded by an atmosphere of business, Christian influence, and a spirit of self-help that seemed to have awakened every faculty in me, and caused me for the first time to realize what it meant to be a man instead of a piece of property.

W.E.B. DuBois might as well have been from a different planet. Born in 1868 in a 99% White town in Massachusetts to a free Black mama who hadn't known slavery for generations, he had the support of his teachers, becoming not only the first Black man to graduate from the high school but also the valedictorian.

His daddy left when he was young and his mama died when he was 16, but W.E.B.'s childhood church raised the funds for him to attend college at Fisk in Tennessee, where he first encountered Jim Crow racism in a fuller form. From there he went on to Harvard and became the first Black man to earn a Harvard Ph.D.

His daddy left when he was young and his mama died when he was 16, but W.E.B.'s childhood church raised the funds for him to attend college at Fisk in Tennessee, where he first encountered Jim Crow racism in a fuller form. From there he went on to Harvard and became the first Black man to earn a Harvard Ph.D.

After graduation W.E.B. wrote to Booker T about working at Tuskegee, but Booker T's offer came too late and W.E.B agreed to teach at Wilberforce U instead. Soon he left and spent a year in Philly to make the first-ever case study of a Black community in the USA.

If there was one thing W.E.B. wanted to fight for, it was for a Black men to have the rights to reach their full potential in American society.

He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

– newspaper editors called it among the most notable speeches ever given in the South. Even President Grover Cleveland gave Booker T his props, resulting in a meeting between them and a friendship that lasted years and led to the president’s support for Tuskegee.

– newspaper editors called it among the most notable speeches ever given in the South. Even President Grover Cleveland gave Booker T his props, resulting in a meeting between them and a friendship that lasted years and led to the president’s support for Tuskegee.

)

)

He published a critical-ass review of Up From Slavery, and even though both sides attempted to minimize their public separation, their beef was set.

He published a critical-ass review of Up From Slavery, and even though both sides attempted to minimize their public separation, their beef was set. when Booker T became the first Black man to have an official private dinner at the White House.

when Booker T became the first Black man to have an official private dinner at the White House.

W.E.B. starts soft, noting how impressive it is for a man from Booker T's following to have accomplished all he has.

W.E.B. starts soft, noting how impressive it is for a man from Booker T's following to have accomplished all he has.

, and Trotter was arrested by the police. W.E.B. wasn't there, but later he came out in support of Trotter's side, and (false) whispers started that W.E.B. had helped plan the whole thing.

, and Trotter was arrested by the police. W.E.B. wasn't there, but later he came out in support of Trotter's side, and (false) whispers started that W.E.B. had helped plan the whole thing.