The Legacy of a Civil Rights Icon’s Vegetarian Cookbook

dikk Gregory was an activist, comedian, and trendsetter for Black vegans.

July 21, 2021

The Legacy of a Civil Rights Icon's Vegetarian Cookbook

For Gregory, who became a vegetarian in 1965, food and diet became inextricably linked to civil rights.

Adrian Miller, the author of

Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue, remembers how for his family, holidays like Juneteenth always meant celebrating with food. “We went to the public celebrations in the Five Points neighborhood, Denver’s historic Black neighborhood. At those events, the celebrated foods were barbecue, usually pork spareribs, giant smoked turkey legs, watermelon, and red-colored drinks.”

To many Black Americans, barbecue and soul food mean victory. Cooking techniques passed down for generations speak to the fortitude and perseverance of Black culture and cuisine. But along with celebration comes the consideration of the health effects of meat, sugar, and fat. Running parallel to the narrative of soul food lies another story, one that ties nutrition with liberation, and one that features an unlikely hero: a prominent Black comedian whose 1974 book filled with plant-based recipes continues to influence Black American diets today.

I grew up with

dikk Gregory’s Natural Diet for Folks Who Eat: Cookin’ With Mother Nature in my home in Memphis. I even took it along with me for my first semester at Tennessee State University. The campus was surrounded with fast-food and soul food restaurants, and I often referred back to Gregory’s book for nutritional advice. I also made recipes from its pages, such as the “Nutcracker Sweet,” a fruit smoothie made with a mixture that would now be known as almond milk. Today, many years later and living in Brooklyn, I still consult the book. The same copy I first saw on my mother’s bookcase—with its cover depicting Gregory’s head wearing a giant chef’s hat topped with fruit and vegetables—now sits on my own.

Now considered one of history’s greatest stand-up comedians, dikk Gregory skyrocketed to fame after an appearance on

The Tonight Show with Jack Paar in 1961, a segment that almost didn’t happen. Gregory initially turned down the opportunity because the show allowed Black entertainers to perform, but not to sit on Parr’s couch for interviews. After his refusal, Parr personally called Gregory to invite him to an interview on the

Tonight Show’s couch. His appearance was groundbreaking: “It was the first time white America got to hear a Black person not as a performer, but as a human being,”

Gregory later said in an interview.

Gregory was particularly adept at using humor to showcase the Black experience at a time of heightened tension and division in the United States. During a performance early in his career, he quipped, “Segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?”

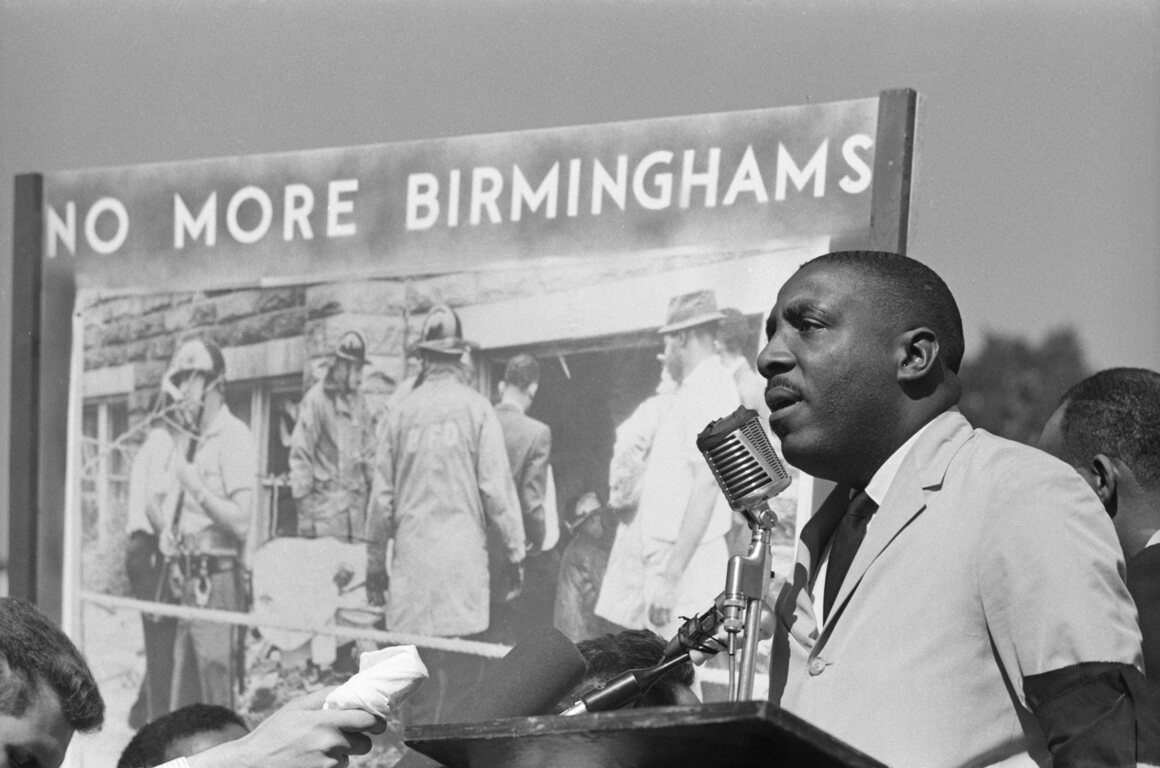

Gregory, addressing a crowd in Washington, DC, in 1963.

“He had the ability to make us laugh when we probably needed to cry,” U.S. representative and civil rights icon John Lewis

said in an interview after Gregory’s death in 2017. “He had the ability to make the whole question of race, segregation, and racial discrimination simple, where people could come together and deal with it and not try to hide it under the American rug.”

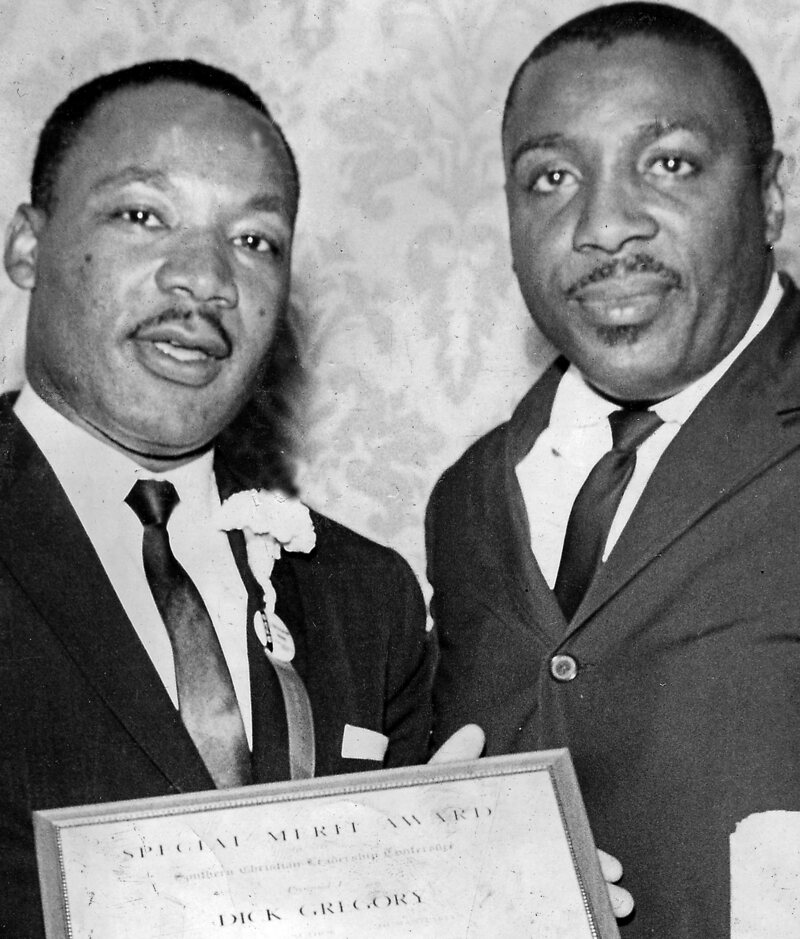

But Gregory didn’t just tackle racial inequality at comedy clubs. He also used his voice to advocate for civil rights at protests and rallies. After emceeing a rally with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in June 1961, Gregory developed a relationship with King. (Gregory’s close ties to leaders like King and Mississippi activist Medgar Evers would eventually lead to his becoming a target of FBI surveillance.) He aided in the search for the missing civil rights workers that were killed by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi during the intense “Freedom Summer” of 1964 and performed at a rally on the last night of 1965’s Selma to Montgomery march.

For Gregory, who became a vegetarian in 1965, food and diet became inextricably linked to civil rights. “The philosophy of nonviolence, which I learned from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., during my involvement in the civil rights movement, was first responsible for my change in diet,” he writes in his book. “I felt the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ applied to human beings not only in their dealings with each other—war, lynching, assassination, murder, and the like—but in their practice of killing animals for food or sport.”

Gregory with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after the comedian won the Merit Award of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1963.

Throughout

dikk Gregory’s Natural Diet, he ties the liberation of Black people to health, nutrition, and basic human rights. Gregory was all too familiar with the socioeconomic obstacles to a healthy diet: Growing up poor in St. Louis, he had limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables. In his book, he notes that readers may not always have the best resources, but they can have the best information. Each chapter serves as both a rallying cry and a manual, offering everything from primers on the human body to lists of foods that are good sources of particular vitamins and minerals.

Thanks to Gregory’s longstanding collaboration with nutritionist Dr.

Alvenia Fulton, the book offers healthy recipes as well as natural remedies for common ailments. The chapter “Mother Nature’s Medicare” includes recipes for everything from party fare (“nature’s champagne”) to headache cures (a mixture of tomato, celery, and onion juice). For those who might want to gain or lose weight, the chapter “dikk Gregory’s Weight-On/Weight-Off Natural Diet” includes recipes for nondairy milks and weekly meal plans.

Gregory’s culinary contributions, rather than being a footnote to his already eventful life, have formed a large part of his legacy. Cliff Notez, a musician and multimedia artist from Boston, has been vegan for four years and embraces much of dikk Gregory’s philosophy. “I think he’s definitely one of the few Black intellectual writers who openly [spoke] about veganism, vegetarianism,” Notez says.

Gregory, with Dr. Alvenia Fulton, one of his nutrition mentors.

While a lot has changed since 1974, there are still obstacles to living a healthy, plant-based lifestyle. As Notez points out, “it can be harder to become vegan in inner city communities” due to persistent food deserts. Countering these challenges is a new generation of Black culinary leaders who continue Gregory’s legacy of empowerment through education. As the chef-in-residence at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora, Bryant Terry runs programs focused on the intersection of food, poverty, and activism. An acclaimed chef who’s published several vegan cookbooks, Terry also cites Gregory as a profound influence.

In an interview with the AARP, he described

dikk Gregory’s Natural Diet as “one of those seminal texts that influenced me to think more about these issues and be invested in shifting my own personal health and well-being.”

Food has always meant more than just health. “Food has a very important role,” says Adrian Miller. “Eating food is something that we all have in common, and that helps create an inviting space where people can come together and have difficult conversations.” dikk Gregory knew food had the power to fuel change. In his book

dikk Gregory’s Political Primer, he writes, “I have experienced personally over the past few years how a purity of diet and thought are interrelated. And when Americans become truly concerned with the purity of the food that enters their own personal systems, when they learn to eat properly, we can expect to see profound changes effected in the social and political system in this nation. The two systems are inseparable.”