You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America

- Thread starter get these nets

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?get these nets

Veteran

Last edited:

get these nets

Veteran

get these nets

Veteran

get these nets

Veteran

get these nets

Veteran

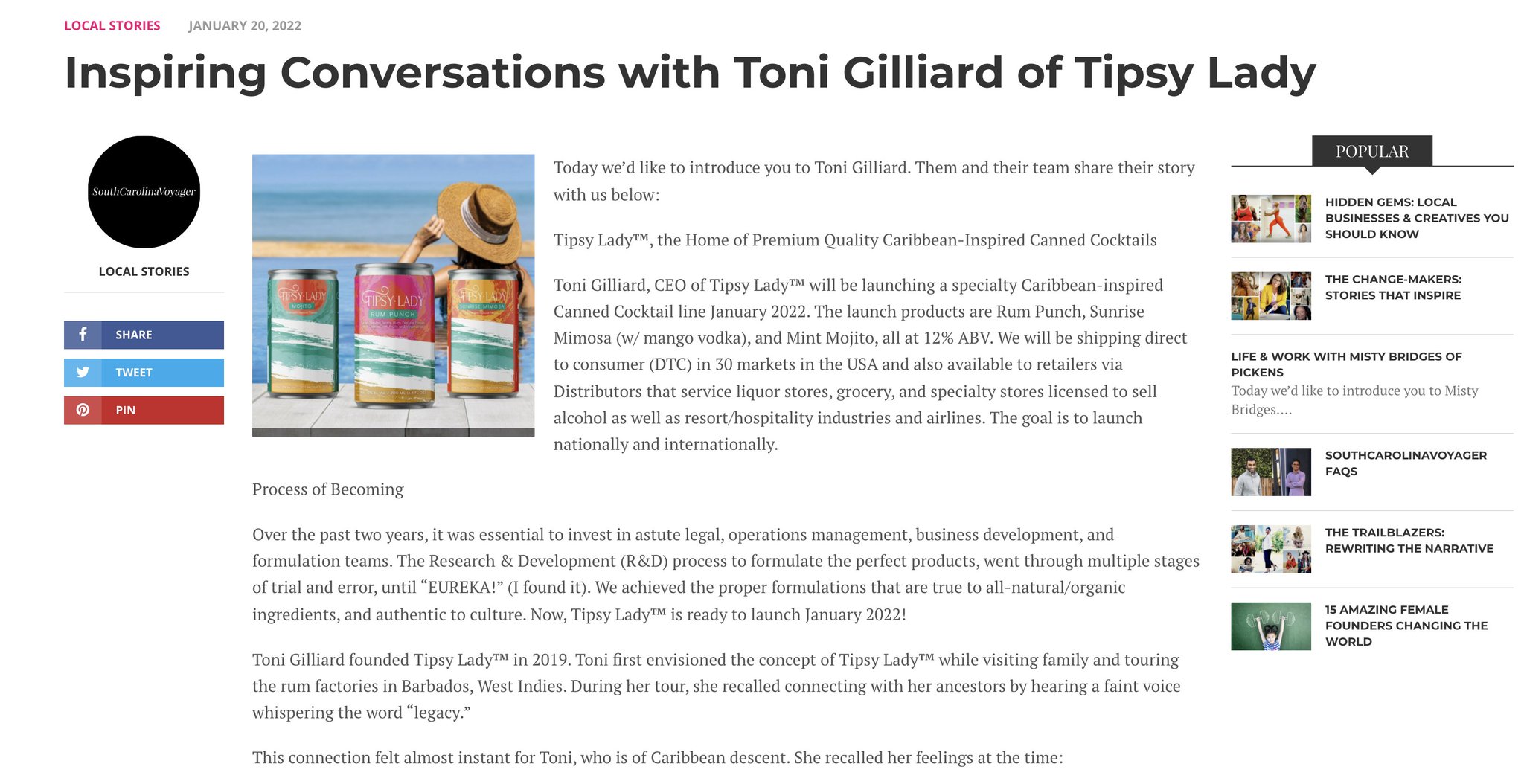

NBA star James Harden releases first wine collection with Accolade Wines

21 July 2022NBA superstar James Harden has teamed up with Accolade Wines to release his first signature wine collection, J-Harden.

The equity partnership, which is a collaboration with Accolade Wines’ Jam Shed brand, is centred around a mission to make quality wine more accessible to all consumers, is scheduled to be available to buy online and through leading retailers across the US from 1 September.

The collection will begin with a California Cabernet Sauvignon and a California Red Blend, and will be distributed by Vivino, Go Puff, Bevmo, and HEB, retailing at US$16.99 per bottle.

Harden said: “My entrance into the wine game is much bigger than just having my own label,” said Harden. “I have always seen the wine industry as a closed-door environment. Through my partnership with Accolade and the release of J-Harden, my goal is to make a high-quality product that can be enjoyed by the masses at a reasonable price. If you’re new to wine or an experienced enthusiast, I believe you’ll love this wine as much as I do.”

According to Accolade Wines, Harden’s involvement in the label goes far beyond an equity stake and combines his love for fashion, art, style, and wine and sawHarden working closely with the team to offer his input on the taste, look, and feel that match his personality. Harden added that his wine will be “smooth, full-bodied, and jammy”.

Enrique Morgan, Accolade’s managing director of the Americas, added: “We share James’ passion for making the wine industry more accessible to the masses. James brings so much positive energy and a high level of enthusiasm to this partnership that will be felt by anyone who picks up a bottle of J-Harden starting in September. We’re thrilled to be part of the same team.”

The J-Harden label will include the likeness of Harden’s beard with bright colours and a floral design inside a silhouette of Harden’s face.

As a 10-time NBA All-Star and third-leading three-point scorer in NBA history, Harden has revealed that he plans to share his personal wine journey with fans on his social media accounts and introduce J-Harden to retailers and shoppers worldwide.

get these nets

Veteran

get these nets

Veteran

Ep 22: Ibraheem Basir, A Dozen Cousins- The Business of Taste, Health, and Culture

Black on Shelf Podcast

May 11 2022

Our childhood experiences have major influences on our present and future, and although some of our childhood experiences were not pleasant, we can always chart a new course by learning from the past and shooting for the stars aiming for greater days ahead. Our guest’s on this episode is Ibraheem Basir, founder of A Dozen’s Cousins, a brand bringing you yummy, good for you and soulfully seasoned beans, bone broth rice, and seasoning sauces all while retaining authenticity Ibraheem and I chatted about the role of food in his big family while growing up. He has nine siblings and a good meal was their way of showing love and celebrating milestones. Nothing beats a good home cooked meal bursting with authentic flavor. Ibraheem Basir combined inspiration from his upbringing and knowledge from work experience in corporate America to found A Dozen Cousins

get these nets

Veteran

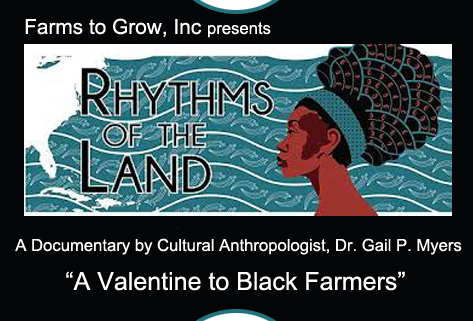

Rhythms of the Land

A large portion of African American sharecroppers and tenant farmers migrated to the North after the Wars I and II for factory jobs. These are the stories of the people that remained on or returned to the land and continued the agrarian traditions passed down from their ancestors.

www.rhythmsoftheland.com

www.rhythmsoftheland.com

THE ORIGIN OF LIMA’S CREOLE STREET FOOD

Oct 9Written By Nico Vera

By Nico Vera

Modern-day anticucheros in Lima. Photo by Nico Vera.

Lima’s love for street food spans centuries. Today, locals in Peru’s coastal capital seek out food carts and market stalls offering traditional creole street food—soothing herbal infusions, ancestral brews, warm tamales, baked empanadas, sugary milk caramel cookies, crispy sweet potato donuts, mashed potato casseroles, smoky beef-heart kebabs and creamy purple corn puddings. But it was Lima’s colonial-era criollos of Spanish, Andean, or Black heritage who first cooked and hawked these dishes. Singing pregones from morning ’til night to announce their wares, they were Lima’s original street food vendors.

During the Viceroyalty of Peru (1542-1824), Spanish colonists brought enslaved people from Africa to Lima, to work in the city or on cotton or sugar coastal plantations. By the time Peru gained its independence (1824) and abolished slavery (1854), Afro-descendants were half of Lima’s population. Though slavery ended, the need for labor in coastal plantations continued. This attracted indentured servants from China, adding to Lima’s racial diversity. Lima’s population growth created a demand for produce markets throughout the city. And from these markets, street food vendors poured into the streets of Lima and created an informal economy.

But who were these vendors? And what did they cook? In the 1872 book Tradiciones Peruanas (Peruvian Traditions), Peruvian writer Ricardo Palma (1833-1919) shares stories of Peru’s history. Some were about Inca traditions or Peru’s independence, but most were about all aspects of creole life in colonial-era Lima. In one story, he documented the daily routine of street food vendors. From 6 a.m. until 8 p.m., they sold drinks and a variety of sweet and savory foods that are still popular today. These are some of the hourly highlights:

7 a.m.: tisanes and chicha

10 a.m.: tamales

12 p.m.: empanadas

1 p.m.: alfajores

2 p.m.: picarones and causa

3 p.m.: anticuchos

7 p.m.: mazamorra morada

After the 6 a.m. milk vendor came the tisanera and chichera at 7 a.m., and according to Palma both were Afro-descendant women. Tisanes are medicinal infusions, made with different curative herbs, that customers often enjoyed for breakfast. Chicha is an ancestral grain brew which the Incas prepared since precolonial times by fermenting corn. Palma says that the chicha vendor hailed from Terranova, an Afro-Peruvian community in Lima.

Savory tamales came at 10 a.m. and empanadas at noon. Colonial foodways brought empanadas from Spain to Peru, and Lima’s creoles sold them, filled with picadillo—ground beef cooked with spices. But the Peruvian tamal has precolonial origins. The Incas prepared tamal-like humitas by boiling grated corn wrapped in leaves. According to anthropologists, Afro-descendant women added savory spices and ingredients to humitas. These creole humitas were similar to Mexican tamales, so that’s what colonists and vendors ended up calling them.

Spanish foodways also brought sweets to colonial Lima, such as alfajores and buñuelos. Derived from a Moorish confection, alfajores are shortbread cookie sandwiches filled with milk caramel and dusted with powdered sugar. Buñuelos are fried dough balls, but Afro-Peruvian cooks transformed them into picarones—doughnut-shaped fritters made with an anise-infused sweet potato and squash dough, then bathed with a cinnamon and clove spiced syrup. Alfajores and picarones were among the first desserts of the afternoon, at 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., respectively.

Then, for a savory midafternoon break, came the 2 p.m. causa. Palma writes that causa was from the northern coastal town of Trujillo, an epicenter of Peru’s independence movement. Causa is a mashed potato dish made with salt, citrus juice, oil and hot peppers, then topped with olives and fried fish or shrimp. Creole cooks today shape the mashed potato into a casserole with different middle layers, such us tuna or chicken salad with onions and mayonnaise. To serve it, they slice into a tall square piece, like a cake. Locals suggest that the name “causa” hinted at Trujillo’s revolutionary past, fighting for a “cause,” for independence. Then, at 3 p.m. came anticuchos, one of Lima’s iconic street foods. Afro-descendants grilled these smoky beef-heart kebabs marinated in vinegar, lime juice, spices and hot peppers.

The last food of the day was ice cream at 8 p.m., but an hour before came mazamorra morada, a creamy purple corn pudding that originated in Andean communities. In Lima, creole cooks prepared it by boiling purple corn with cinnamon, cloves and fruit peel to create a stock. Then, they added sugar, lime juice and sweet potato flour to thicken it. Palma’s story says the vendor was a woman, or mazamorrera. This dessert is so popular in Lima today that Limeños (people from Lima) proudly call themselves “mazamorreros”—meaning “those who eat mazamorra.”

From Palma’s account of the food vendors’ schedule, it would seem that Limeños ate all day long. Palma also tells us that vendors sang pregones to describe their foods and attract customers. Other writers, contemporaries of Palma, documented these pregones—which were only sung in Lima—and detailed how they were sung, what tone the vendor’s used.

Twentieth-century Afro-Peruvian musician Victoria Santa Cruz recreated those calls in the a cappella song “GRITOS DE PREGONEROS.” The chichera, for example, sang: “chicha que el cuerpo mejora y acaba con la desdicha.” She promised that drinking chicha betters the body and ends misery. While the tisanera announced her arrival, bringing fresh tisana with shaved ice and pineapple: “la tisanera llegó, aquí está la tisanera, tisana con nieve y piña, ¡tisana!, tisana fresca.”

La Tisanera (1850) by Pancho Fierro. Via Wikimedia Commons

The complement to Palma’s writings are the watercolor paintings of Pancho Fierro (1807-1879). In lieu of photographs, some of his illustrations are a visual record of street food vendors in Lima circa 1850. Fierro draws the tisanera as a Black woman on foot, balancing a large vase with tisane on her head, and holding a smaller basket with cups. The tamalera is also an Afro-descendant woman, but she is riding a mule carrying two baskets filled with tamales. And the anticuchero, an Afro-descendant man, is sitting on a wood crate while grilling anticuchos. The almuerzera, a Black woman who cooks lunch, is seen announcing her food, child in tow.

Creole street food has been a constant in Lima for centuries. Today, the pregones are gone, but locals and tourists rush Grimanesa’s Anticuchos at the annual outdoor Mistura food festival, or frequent Parque Kennedy in Miraflores for push cart vendors like Picarones Mary. Near the north east corner of the park, across Avenida Jose Larco, stands Ibero Librerias, a bookstore that carries an exhaustive collection of Peruvian cookbooks. Their street food recipes closely resemble those in early creole cookbooks, such as “El Nuevo Manual de la Cocina Criolla (Lima, 1903).” And through these traditional recipes, Lima has maintained a strong connection to a past that evokes culinary nostalgia for the street food vendors of yesteryear.

The Origin of Lima’s Creole Street Food — Whetstone Magazine

Colonial-era criollo cooks created a culinary culture that’s still alive today.

get these nets

Veteran

Ghetto Gastro's Black Power Kitchen at The Met

Date and Time

October 19, 2022

The Met Fifth Avenue

The Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium

Details

Jon Gray, Met Civic Practice Partnership alumnus, author, and Ghetto Gastro cofounder

Pierre Serrao, author, Ghetto Gastro cofounder and chef

Lester Walker, author, Ghetto Gastro cofounder and chef

Osayi Endolyn, author

Jessica B. Harris, culinary historian

Join Ghetto Gastro for an evening celebrating the launch of their first cookbook, Black Power Kitchen. Ghetto Gastro is a culinary collective that uses food as a platform to spark conversation about larger issues surrounding inclusion, race, access, and how food—and knowing how to cook—provides freedom and power.

This panel conversation, moderated by Jessica B. Harris, PhD, culinary historian, and author of the New York Times bestseller, High on the Hog, centers on Black culinary traditions and food and art as tools for resistance.

get these nets

Veteran

*gotta see this commercial

10/31/22

Vaucresson sausage has been a continuous part of the landscape of Creole flavor in New Orleans for generations, though it was laid low by the levee failures in 2005. Its long-time butcher shop and production facility on St. Bernard Avenue were wrecked, and attempts to bring it back stalled out through the years.

Vance Vaucresson kept the business going, however, using other facilities and making sure these flavors remained in rotation, by direct order and at events. Community support and encouragement kept the enterprise going and the wheels turning toward a full reopening.

“There were layers of conflict between us getting here, but at every step there was someone saying how they needed us to come back, how they needed to get this sausage again," Vaucresson said.

Vaucresson opened the new Vaucresson’s Creole Café & Deli at the former butcher shop's original address. He brought it together with a partnership that includes the nonprofit Crescent City Community Land Trust, Liberty Bank and Edgar Chase IV, chef at his family’s famous Dooky Chase’s Restaurant.

While the footprint is the same, the structure is a complete rebuild and has been thoroughly redesigned along modern lines.

Vaucresson is on a mission and he sees the shop and café as a hub to propel it.

“It’s all about telling the story of our Creole culture and how so much of that comes through food and families, and that’s what you can connect here,” he said. “People out there are yearning for those connections to what once was

get these nets

Veteran

Meet the Black Entrepreneurs Carving a Path In the Distillery Community

Nov 1, 2022

A highly regulated industry presents additional challenges.

Timothy Irving Jr. is simply following in the family business. His family grew up in segregated rural Georgia where there weren’t a lot of opportunities for Black people. “The family struggled. My uncle, who was one of 16, took a lot of risks and had to be creative to support the family.”

His uncle went into the bootleg moonshine business, and Irving is “paying homage, acknowledging his efforts of what he had to do in order to support all of us,” he said. Today, Irving is in the spirits business — legally — with The Original Irving Whiskey, a bourbon whiskey.

Credit: Josh Williams

Increasingly a number of Black-owned spirit brands and distilleries are cropping up across the country. Industry experts guess there are about 200 brands, several in the metro area. A decade or so ago, there were just a handful. According to the America Craft Spirits Association’s CEO Margie Lehrman, in 2010 there were fewer than 100 craft distilleries; today there are about 2,300. Fewer than 50 are minority owned.

Foot in the door

Admittedly anyone on an entrepreneurial path faces challenges but the spirits industry is particularly hard due to a multitude of local, state and federal regulations and a crowded competitive field. It’s just a wee bit harder for people of color and minority women.

“It’s a challenge trying to break into these big distributors and I’m not sure we’ve gained their respect, especially being a small Black-owned brand. It’s a little bit of a challenge to prove ourselves. We just want the opportunity,” said Irving.

Ricardo Kelly, who owns Kelly Family Distributors, a Black-owned spirits distributor in Alpharetta that helps create, develop and import minority brands, agrees. He works with 14 Black-owned brands; four are female owned. “I think it’s a bigger problem being a minority woman,” he says.

“My perception is that males are taken more seriously. One, retailers don’t take us seriously and two, everyone wants to know who you are and how long you’ve been in business. There’s a lot more questioning.”

TK Burton-Johnson and her brother, Ty, started Red Hazel Brewing Co. which produces a spiced rye whiskey. “I am a woman in the whiskey industry, not just a woman but a Black woman. Sometimes when you’re talking to people you get looks like ‘You’re not supposed to be in this room’. I don’t have to necessarily be rude to get respect but I do have to be more assertive. It starts with respect; that respect is starting to come.”

Funding

Start-up money is often an entrepreneur’s nightmare and, the spirits sector is particularly hard to crack financially. “The proverbial saying in this industry is that if you want to make a million dollars, invest two million,” said Chris Montana, founder and owner of the first Black-owned distillery, Minneapolis-based Du Nord Craft Spirits.

“There are investment patterns,” said Giacomo Negro, a professor of organization and management at the Goizueta Business School at Emory University. “Funding is characterized by social factors and tends to come from sources who are familiar with the people they do business with and that may be a disadvantage to minorities.”

Lehrman said there is “no path into the distillery community. Everything is from private investment firms and that’s somewhat limited. African Americans have a hard time. Banks don’t lend money where there’s no economic history.”

Don and Nayana Ferguson founded Anteel Tequila in 2017, making Nayana the first Black woman to own a tequila brand. The couple, both “high earners who saved,” didn’t need outside capital. Their next round will be with friends and family. “We won’t go to a bank,” she said.

Caption

Credit: Manna Ibanez

They produce Anteel Reposado Tequila, aged eight months in charred Tennessee whiskey barrels; Anteel Blanco Tequila; Anteel Coconut Lime Blanco Tequila infused with coconut and lime; and Blanco Tequila infused with Tarocco blood oranges from Sicily.

Montana, a former president of the ACSA, produces seven house-made brands as well as working with other brands. There is “skepticism. You’re doing business with people who aren’t use to seeing people like you. When I went to get funding we struck out. Others were raising $1 million; not me. I got $60,000 from a community development organization. There’s a disconnect.”

Not helping is that the industry is capital intensive upfront, meaning all the money is spent before a bottle is sold. “There are people who can self-fund; that’s not the norm. For most it’s a second career,” said Montana. “Rarely do you have someone say ‘I have a large fortune and I’m desperate to make it a small one’. Usually it’s family, friends and maybe Go Fund Me.”

Burton-Johnson’s funding was “strictly bootstrapping. We didn’t think we’d qualify for a bank loan. I’ve applied for more than 200 grants and haven’t gotten any.”

Getting started

There are two paths to a spirits company. One is to the create the formula and then distill it yourself, and handle supply chain issues such as sourcing the ingredients, creating labels, finding bottle manufacturers, transportation and marketing. Another is to create the product and work with a distributor who does it all.

Another snag is a post-Prohibition three-tier marketing chain of production, distribution and sales that is not usually found in other industries. Each step has a mark-up. The first tier is the producer/importer, which in many states requires them to sell to distributors who then sell to stores, bars and restaurants. Distributors must hold state-issued permits for every state they do business in — again not standard.

The restrictions hinder sales and growth. Someone wanting to buy a spirit in Georgia that isn’t available in that person’s home state, for instance, cannot buy several bottles and have them shipped, like wine.

“It’s convoluted,” admitted Lehrman.

Marketing

The next problem is getting the product onto retail shelves and restaurants, and to be fair, “finding distribution is not a problem limited to any ethnic group,” said Lerhman.

Irving and Burton-Johnson used social media and conducted taste testings. Burton-Johnson goes to more than 200 festivals a year; her whiskey is in 45 restaurants and retail outlets.

Ferguson’s liquors are in 13 states and the Caribbean. “We make a product where there are no sugars nor synthetics. I’m a cancer survivor and can’t drink a spirit with extra sweetness. A lot of distributors weren’t willing to try my brand because I’m a Black woman. I’m proving them wrong. I’m going to become a nationally recognized brand, maybe internationally.”

Adding, “Companies haven’t marketed bourbon to Black people. I certainly feel there is a shift in terms of supporting Back-owned companies. I see a boom in people going into stores and looking for Black-owned brands.”

Irving calls this lack of marketing to the Black community a “lost opportunity.” He’s in more than 35 locations throughout metro Atlanta and “making his way to middle Georgia.”

Montana is optimistic. “If you have a good product, ultimately you’ll skip ahead of celebrities and the major brands. You do quickly realize how hard it is to sell a single bottle but once people taste it, everyone will want to have it.”