She had very aggressive Cervical cancer I think and that’s what killed her. They also placed Radium inside her Vaginally as a treatment.this is crazy

did she get cancer because of the cells or because they were messing with her?

does everyone with cancer have these cells? no right?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Henrietta Lacks (dont ever forget her name) black woman true life x-men from storm :

- Thread starter BlackDiBiase

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Ya' Cousin Cleon

OG COUCH CORNER HUSTLA

I remember my auntine telling me this when I was little.

BlackDiBiase

Superstar

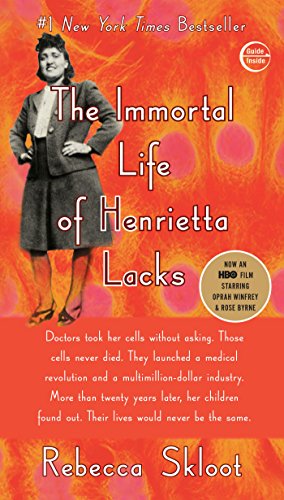

The book is amazing and a must read.

do you believe in the spiritual realm? does it make you believe in the spiritual realm?

might give the book a read, i might just buy it as a gift for someone in the family then borrow it later

I learned about her from this bookit was brother polights old breakfast club interview with metta world peace that put me on. incredible.

get these nets

Veteran

Family of Henrietta Lacks hires civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who says they plan to sue pharmaceutical companies

Jul 29, 2021

The family of Henrietta Lacks has hired a prominent civil rights attorney who says he plans to seek compensation for them from big pharmaceutical companies across the country that made fortunes off medical research with her famous cancer cells.

An attorney for the Lacks family said a legal team is investigating lawsuits against as many as 100 defendants, mostly pharmaceutical companies, but they haven’t ruled out a case against the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

A Hopkins doctor collected a sample of cancer cells from the young mother without her knowledge or permission nearly 70 years ago. Those cells — the first to live outside the body in a glass tube — brought decades of medical advances.

Dubbed the “HeLa” cells, they have been used to develop everything from COVID-19 vaccines to sunscreen, attorney Ben Crump said. He said it’s an example of the long and troubling history of the medical exploitation of Black people in America.

“Never was that more apparent than with the tragedy of how they exploited Henrietta Lacks,” he said

this is crazy

did she get cancer because of the cells or because they were messing with her?

does everyone with cancer have these cells? no right?

she got cancer, they harvested the cells and found hers were the only ones, at that point in time, that could be cultured and replicate indefinitely.

Cancer is indefinite cell replication (with a given nutrient source).

Not every cancer has these cells, but these cells are a good way to test similar cancers, HeLa cells could be like paint swatches before you paint a whole wall. Let's try it out in HeLa, then we'll move on to more atypical cell types.

TheAnointedOne

Superstar

fukked up story

get these nets

Veteran

Estate of Henrietta Lacks sues biotech company over use of famous cells

The so-called HeLa cells removed from Henrietta Lacks during cancer treatment have the unique ability to regenerate endlessly.

October 4, 2021

Attorney Ben Crump, center, holds the great-grandson of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells have been used in medical research without her permission, outside the federal courthouse in Baltimore in Monday, Oct. 4, 2021. (Steve Ruark/AP)

BALTIMORE (CN) — Likening his grandmother's famous cancer cells to the woman herself, and their sale as akin to slavery, the executor of the estate of Henrietta Lacks filed a federal lawsuit Monday against Thermo Fisher Scientific seeking all of the biotechnology company’s profits from her cells.

"Black people have the right to control their bodies," according to the complaint filed in Baltimore federal court by civil rights attorneys Ben Crump and local counsel Kim Parker. “And yet Thermo Fisher Scientific treats Henrietta Lacks’ living cells as chattel to be bought and sold."

The suit is the latest salvo in the Baltimore family's troubled history with Johns Hopkins Hospital, whose doctors treated Lacks' cancer – and removed some of her cells – in 1951, before modern notions of informed consent took hold.

Used by medical researchers for decades and made famous by science writer Rebecca Skloot in her 2010 book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks," the so-called HeLa cells – part of a cancerous tumor cut from Lacks' cervix – have the unique ability to regenerate endlessly.

Johns Hopkins gave the cells to researchers in the interest of science but hid Lacks' identity for decades after the discovery, only revealing the source of the remarkable cell culture in the early 1970s.

Hundreds if not thousands of medical discoveries have been made and tested using the cells, which were even shot into space to assess the effect of zero gravity on human tissue.

"Thermo Fisher Scientific’s business is to commercialize Henrietta Lacks’ cells—her living bodily tissue—without the consent of or providing compensation to Ms. Lacks’ estate," the lawsuit states. "All the while, Thermo Fisher Scientific understands—indeed, acknowledges on its own website—that this genetic material was stolen from Ms. Lacks. Thermo Fisher Scientific’s business is nothing more than a perpetuation of this theft."

Thermo Fisher did not respond to emailed requests for comment Monday.

Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. headquarters in Waltham, Mass. (Stephan Savoia/AP)

A spokeswoman for Johns Hopkins University pointed to a page on the institution's web site honoring Lacks. It is also planning to name a research building after her.

Some of the Lacks' descendants, claiming they were stonewalled by Johns Hopkins and disrespected by Skloot, have been trying to get paid for more than a decade. A previous suit against the hospital was announced in 2017, though it is unclear whether it was ever filed.

During a July press conference, the estate’s attorney, Crump – famous for his flamboyant representation of the families of Michael Brown, George Floyd and other victims of police violence – announced new lawsuits would be forthcoming, possibly against more than 100 pharmaceutical companies.

“The family has not received anything from that theft of her cells, and they treated her like a specimen, like a lab rat like she wasn’t human, with no family, no babies, no husband that loved her,” Kimberley Lacks, the granddaughter of Henrietta Lacks, said at the time.

Monday’s lawsuit was brought by Ron L. Lacks, the estate's executor and grandson of Henrietta Lacks.

“It seems that my family has been shut out of everything profit-bearing of my grandmother and our family history,” he told the Dundalk Eagle last year in a story promoting his book, "Henrietta Lacks the Untold Story," which he says aims to correct misimpressions left by Skloot's book.

The complaint mentions the Tuskegee experiments, in which Black men were secretly denied treatment for syphilis, along with World War II mustard gas experiments on Black soldiers and hysterectomies that were performed on Black women in Mississippi under the guise of appendectomies.

“Too often, the history of medical experimentation in the United States has been the history of medical racism,” the lawsuit states.

In 2013, the National Institutes of Health announced new ethical guidelines concerning HeLa cells, restricting access to the complete DNA sequence to "scientific researchers funded by U.S. government grants

The so-called HeLa cells removed from Henrietta Lacks during cancer treatment have the unique ability to regenerate endlessly.

October 4, 2021

Attorney Ben Crump, center, holds the great-grandson of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells have been used in medical research without her permission, outside the federal courthouse in Baltimore in Monday, Oct. 4, 2021. (Steve Ruark/AP)

BALTIMORE (CN) — Likening his grandmother's famous cancer cells to the woman herself, and their sale as akin to slavery, the executor of the estate of Henrietta Lacks filed a federal lawsuit Monday against Thermo Fisher Scientific seeking all of the biotechnology company’s profits from her cells.

"Black people have the right to control their bodies," according to the complaint filed in Baltimore federal court by civil rights attorneys Ben Crump and local counsel Kim Parker. “And yet Thermo Fisher Scientific treats Henrietta Lacks’ living cells as chattel to be bought and sold."

The suit is the latest salvo in the Baltimore family's troubled history with Johns Hopkins Hospital, whose doctors treated Lacks' cancer – and removed some of her cells – in 1951, before modern notions of informed consent took hold.

Used by medical researchers for decades and made famous by science writer Rebecca Skloot in her 2010 book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks," the so-called HeLa cells – part of a cancerous tumor cut from Lacks' cervix – have the unique ability to regenerate endlessly.

Johns Hopkins gave the cells to researchers in the interest of science but hid Lacks' identity for decades after the discovery, only revealing the source of the remarkable cell culture in the early 1970s.

Hundreds if not thousands of medical discoveries have been made and tested using the cells, which were even shot into space to assess the effect of zero gravity on human tissue.

"Thermo Fisher Scientific’s business is to commercialize Henrietta Lacks’ cells—her living bodily tissue—without the consent of or providing compensation to Ms. Lacks’ estate," the lawsuit states. "All the while, Thermo Fisher Scientific understands—indeed, acknowledges on its own website—that this genetic material was stolen from Ms. Lacks. Thermo Fisher Scientific’s business is nothing more than a perpetuation of this theft."

Thermo Fisher did not respond to emailed requests for comment Monday.

Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. headquarters in Waltham, Mass. (Stephan Savoia/AP)

A spokeswoman for Johns Hopkins University pointed to a page on the institution's web site honoring Lacks. It is also planning to name a research building after her.

Some of the Lacks' descendants, claiming they were stonewalled by Johns Hopkins and disrespected by Skloot, have been trying to get paid for more than a decade. A previous suit against the hospital was announced in 2017, though it is unclear whether it was ever filed.

During a July press conference, the estate’s attorney, Crump – famous for his flamboyant representation of the families of Michael Brown, George Floyd and other victims of police violence – announced new lawsuits would be forthcoming, possibly against more than 100 pharmaceutical companies.

“The family has not received anything from that theft of her cells, and they treated her like a specimen, like a lab rat like she wasn’t human, with no family, no babies, no husband that loved her,” Kimberley Lacks, the granddaughter of Henrietta Lacks, said at the time.

Monday’s lawsuit was brought by Ron L. Lacks, the estate's executor and grandson of Henrietta Lacks.

“It seems that my family has been shut out of everything profit-bearing of my grandmother and our family history,” he told the Dundalk Eagle last year in a story promoting his book, "Henrietta Lacks the Untold Story," which he says aims to correct misimpressions left by Skloot's book.

The complaint mentions the Tuskegee experiments, in which Black men were secretly denied treatment for syphilis, along with World War II mustard gas experiments on Black soldiers and hysterectomies that were performed on Black women in Mississippi under the guise of appendectomies.

“Too often, the history of medical experimentation in the United States has been the history of medical racism,” the lawsuit states.

In 2013, the National Institutes of Health announced new ethical guidelines concerning HeLa cells, restricting access to the complete DNA sequence to "scientific researchers funded by U.S. government grants

BaltimoreTwilightMarauder

Superstar

"x-men from storm"

get these nets

Veteran

This country rose to global prominence by exploiting the bodies of AAs. Still doing it.This should have already been a big budget Hollywood movie to bring awareness to one of the most blatant examples of cacs fukking us over

Keep_It_Hip_Hop_Fam

All Star

More awareness is needed

Evil fukks

Evil fukks