loyola llothta

☭☭☭

Canadian Military in Haiti. Why?

22 February 2019

Canadian troops may have recently been deployed to Haiti, even though the government has not asked Parliament or consulted the public for approval to send soldiers to that country.

The original source of this article is Yves Engler

Copyright © Yves Engler, Yves Engler, 2019

22 February 2019

Canadian troops may have recently been deployed to Haiti, even though the government has not asked Parliament or consulted the public for approval to send soldiers to that country.

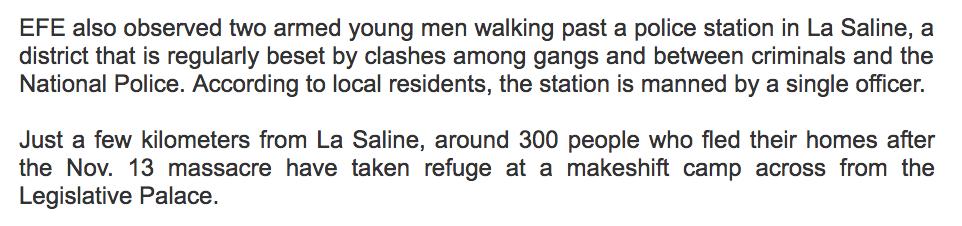

Last week the Haiti Information Project photographed heavily-armed Canadian troops patrolling the Port-au-Prince airport. According to a knowledgeable source I emailed the photos to, they were probably special forces. The individual in “uniform is (most likely) a member of the Canadian Special Operations Regiment (CSOR) from Petawawa”, wrote the person who asked not to be named. “The plainclothes individuals are most likely members of JTF2. The uniformed individual could also be JTF2 but at times both JTF2 and CSOR work together.” (CSOR is a sort of farm team for the ultra-elite Joint Task Force 2.)

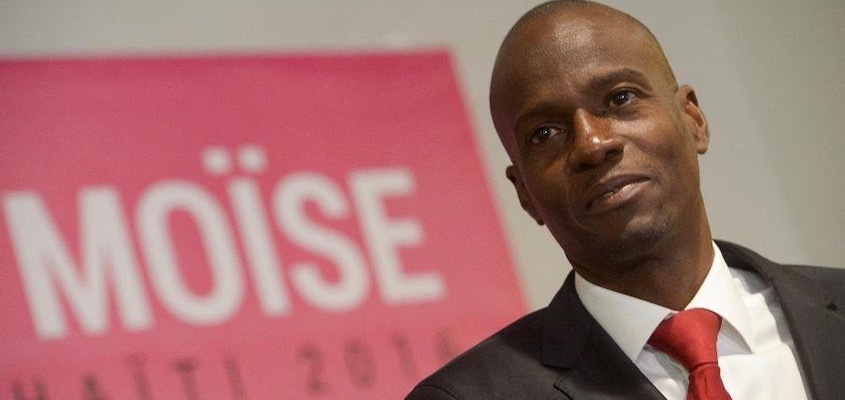

What was the purpose of their mission? The Haiti Information Project reported that they may have helped family members of President Jovenel Moïse’s unpopular government flee the country. HIP tweeted, “troops & plainclothes from Canada providing security at Toussaint Louverture airport in Port-au-Prince today as cars from Haiti’s National Palace also drop off PHTK govt official’s family to leave the country today.”

Many Haitians would no doubt want to be informed if their government authorized this breach of sovereignty. And Canadians should be interested to know if Ottawa deployed the troops without parliamentary or official Haitian government okay. As well any form of Canadian military support for a highly unpopular foreign government should be controversial.

Two days after Canadian troops were spotted at the airport five heavily armed former US soldiers were arrested. The next day the five Americans and two Serbian colleagues flew to the US where they will not face charges. One of them, former Navy SEAL Chris Osman, posted on Instagram that he provided security “for people who are directly connected to the current President” of Haiti. Presumably, the mercenaries were hired to squelch the protests that have paralyzed urban life in the country. Dozens of antigovernment protesters and individuals living in neighborhoods viewed as hostile to the government have been killed as calls for the president to step down have grown in recent months.

Was the Canadians deployment in any way connected to the US mercenaries? While it may seem far-fetched, it’s not impossible considering the politically charged nature of recent deployments to Haiti.

After a deadly earthquake rocked Haiti in 2010 two thousand Canadian troops were deployed while several Heavy Urban Search Rescue Teams were readied but never sent. According to an internal file uncovered through an access to information request, Canadian officials worried that “political fragility has increased the risks of a popular uprising, and has fed the rumour that ex-president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, currently in exile in South Africa, wants to organize a return to power.” The government documents also explain the importance of strengthening the Haitian authorities’ ability “to contain the risks of a popular uprising.”

The night president Aristide says he was “kidnapped” by US Marines JTF2 soldiers “secured” the airport. According to Agence France Presse, “about 30 Canadian special forces soldiers secured the airport on Sunday [Feb. 29, 2004] and two sharpshooters positioned themselves on the top of the control tower.” Reportedly, the elite fighting force entered Port-au-Prince five days earlier ostensibly to protect the embassy.

Over the past 25 years Liberal and Conservative governments have expanded the secretive Canadian special forces. In 2006 the military launched the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM) to oversee JTF2, the Special Operations Regiment, Special Operations Aviation Squadron and Canadian Joint Incident Response Unit.

CANSOFCOM’s exact size and budget aren’t public information. It also bypasses standard procurement rules and their purchases are officially secret.While the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment and other government agencies face at least nominal oversight, CANSOFCOM does not.

During a 2006 Senate Defence Committee meeting CANSOFCOM Commander Colonel David E. Barr responded by saying, “I do not believe there is a requirement for independent evaluation. I believe there is sufficient oversight within the Canadian Forces and to the people of Canada through the Government of Canada — the minister, the cabinet and the Prime Minister.”

The commander of CANSOFCOM simply reports to the defence minister and PM.

“Even the U.S. President does not possess such arbitrary power,” notes Michael Skinner in a CCPA Monitor story titled “Canada’s Ongoing Involvement in Dirty Wars.”

This secrecy is an important part of their perceived utility by governments. “Deniability” is central to the appeal of special forces, noted Major B. J. Brister. The government is not required to divulge information about their operations so Ottawa can deploy them on controversial missions and the public is none the wiser. A 2006 Senate Committee on National Security and Defence complained their operations are “shrouded in secrecy”. The Senate Committee report explained, “extraordinary units are called upon to do extraordinary things … But they must not mandate themselves or be mandated to any role that Canadian citizens would find reprehensible. While the Committee has no evidence that JTF2 personnel have behaved in such a manner, the secrecy that surrounds the unit is so pervasive that the Committee cannot help but wonder whether JTF2’s activities are properly scrutinized.” Employing stronger language, right wing Toronto Sun columnist Peter Worthington pointed out that, “a secret army within the army is anathema to democracy.”

If Canadian special forces were secretly sent to Port-au-Prince to support an unpopular Haitian government Justin Trudeau’s government should be criticized not only for its hostility to the democratic will in that country but also for its indifference to Canadian democracy.

Featured image is from HIP

The original source of this article is Yves Engler

Copyright © Yves Engler, Yves Engler, 2019