The Greek government is urging a no vote in Sunday’s bailout referendum. Eurozone leaders say vote yes

A demonstrator wears ‘oxi’ (no) stickers during an anti-austerity rally in Athens. Photograph: Yannis Behrakis/Reuters

Katie Allen

Saturday 4 July 2015 04.22 AESTLast modified on Saturday 4 July 2015 05.16 AEST

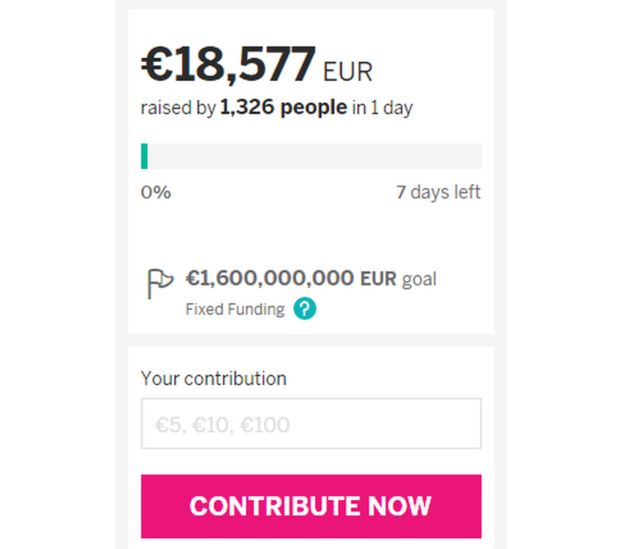

Greeks go to the polls on Sunday to vote on whether to acceptthe bailout programme proposed by international lenders that would restart financial aid in exchange for further austerity and economic reform.

The government is urging people to vote no, with the finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis, saying it is time to end years of rolling over Greece’s bailouts and “pretending” its debts can be repaid.

But

Eurozone leaders have insisted that if Greece votes no, it will be saying goodbye to the euro. Two former Greek prime ministers, Kostas Karamanlis and Antonis Samaras, both of the centre-right New Democracy party, are urging a yes vote, saying that a return to the drachma would kill the Greek economy.

So how do top economists say they would vote - and why?

Joseph Stiglitz - NO

Nobel laureate in economics and professor at Columbia University

Stiglitz has decried the economics behind the international creditors’ programme for Greece as “abysmal”. “I can think of no depression, ever, that has been so deliberate and had such catastrophic consequences,” he

wrote this week.

He says it is hard to advise Greeks how to vote on 5 July, given both options carry “huge risks”. But it is clear the Nobel laureate himself would vote no:

A no vote would at least open the possibility that Greece, with its strong democratic tradition, might grasp its destiny in its own hands. Greeks might gain the opportunity to

shape a future that, though perhaps not as prosperous as the past, is far more hopeful than the unconscionable torture of the present.

Paul Krugman - NO

Nobel prize-winning US economist

“I would vote no, for two reasons,” Krugman

wrote in the New York Times.

Firstly, thinks Krugman, the troika of international lenders – the entity consisting of the European commission, the

European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund – is effectively demanding that the policy regime of the past five years be continued indefinitely: “Where is the hope in that?”

Secondly, the political implications of a yes vote would be “deeply troubling”, he says.

The troika clearly did a reverse Corleone – they made Tsipras an offer he can’t accept, and presumably did this knowingly. So the ultimatum was, in effect, a move to replace the Greek government. And even if you don’t like Syriza, that has to be disturbing for anyone who believes in European ideals.

Thomas Piketty - NO

Professor at the Paris School of Economics and author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Piketty has joined other economists in calling for Greece’s heavy debt burden to be restructured and says Greeks should vote no. In an interview with the

French broadcaster BFMTV he described the deal proposed by creditors as “bad”. He also warned that expelling Greece from Europe would push it into the arms of Russia.

It’s a complicated choice. The question being asked is whether the plan from the creditors is good or not. If that is the question being asked, the answer for me is clear: it is a bad plan.

Jeffrey Sachs - NO

Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University and author of The Price of Civilization

Sachs sees a way out of the crisis if Greece’s debt burden is eased while keeping the country in the eurozone. For that to happen Greece and Germany need to come to a “rapprochement” soon after the referendum and agree to a package of economic reforms and debt relief, he

wrote on Project Syndicate. But first Greeks must vote against international creditors’ proposals .

I recommend that the Greek people give a resounding “No” to the creditors in the referendum on their demands this weekend.

Christopher Pissarides - YES

British-Cypriot economist and Nobel laureate

Pissarides says the austerity forced on

Greece has been detrimental and is probably “the biggest factor behind its very high and long-lasting unemployment rates”. But he does not believe voting no on Sunday is the answer.

“A

yes vote is still the best option, by a long shot,” he

wrote on the Guardian website.

The way forward is to reform from within, not by running away from the problem. There are already signs that sentiments are changing ... With patience other changes will follow. It is clear to most politicians in

Europe that austerity is dividing the continent and damaging the European project. Reforms will follow. Greece has a role to play in this agenda but only if it stays within the eurozone.

Vicky Pryce - YES

Chief economic adviser at the Centre for Economic and Business Research

Pryce believes

both sides are equally to blame in letting the Greek debt crisis get to a point now fraught with immense political and economic risks for the entire eurozone. “The referendum should never have been held. But I would vote yes,” she says.

There has been too much austerity but a no vote would make things worse. It would almost certainly mean banks becoming insolvent, an exit from the euro and a much faster decline in economic activity, with hyperinflation following as the drachma that is introduced instantly devalues.

A yes vote would keep banks open and give mandate for a deal to be struck that recognises the new Greek realities and includes, as the IMF now says, restructuring of the debt which every economist knows is unsustainable.

Professors of economics at Greek universities - YES

In an

open letter, 246 professors at economics schools and universities in Greece urged people to vote yes on Sunday or risk leaving the EU.

Taking into account that the proposals of our creditors and the Greek government were converging until last Friday, we believe that what is really at stake in the coming referendum, irrespective of the precise formulation of the question, is whether

Greece will remain, or not, in the eurozone and, possibly, whether it will remain in the EU itself...

Leaving the eurozone, especially in this chaotic and superficial way, would likely lead to a process of leaving the EU too, with unpredictable and disastrous consequences for the national security and the democratic stability of our country.