You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Federal Reserve 100 Years of Failure

- Thread starter Scientific Playa

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Abolish really. But that's not gonna happenare you actually arguing for the Government to come in and regulate something?

I don't believe there is anything wrong with having a set amount currency

We don't need inflation.

We don't need inflation.ill

Superstar

for starters we does the fed reserve act in secrecy?

why doesn't stuff like this hit the mainstream media

their system is a lie..

If the Federal Reserve is a private entity then they have no obligation to divulge information to the public.

The US holds $177 Billion in gold for the Germans. The German GDP is over $3 trillion a year. Their gold holdings are irrelevant to their economy.

you niccas troll about how the fed reserve should be run depending on your private jewish arguments.If the Federal Reserve is a private entity then they have no obligation to divulge information to the public.

The US holds $177 Billion in gold for the Germans. The German GDP is over $3 trillion a year. Their gold holdings are irrelevant to their economy.

177, 3 trillion. so that's the numbers the jews cooked up to steal their gold?

you know if they can pull this sh1t on white ppl what they've done to gold belonging to 3rd world countries..

you know if they can pull this sh1t on white ppl what they've done to gold belonging to 3rd world countries..i have to go play some stupid ass board games. but i had to respond to this quickie. just accept defeat and not make this an all nighter.

If the Federal Reserve is a private entity then they have no obligation to divulge information to the public.

The US holds $177 Billion in gold for the Germans. The German GDP is over $3 trillion a year. Their gold holdings are irrelevant to their economy.

Domingo Halliburton

Handmade in USA

you niccas troll about how the fed reserve should be run depending on your private jewish arguments.

177, 3 trillion. so that's the numbers the jews cooked up to steal their gold?you know if they can pull this sh1t on white ppl what they've done to gold belonging to 3rd world countries..

i have to go play some stupid ass board games. but i had to respond to this quickie. just accept defeat and not make this an all nighter.

so youre not American?

ill

Superstar

@Ill nicca admit the jews in the fed reserves (and wall street) are theives who've ruined america and the world economy. and used the zionist media to do it. admit it. admit it.

Greedy Wall St execs may have stolen your money. Classifying all Jews in that category is ignorant. Its class warfare. Not religious warfare.

ill

Superstar

you niccas troll about how the fed reserve should be run depending on your private jewish arguments.

177, 3 trillion. so that's the numbers the jews cooked up to steal their gold?you know if they can pull this sh1t on white ppl what they've done to gold belonging to 3rd world countries..

i have to go play some stupid ass board games. but i had to respond to this quickie. just accept defeat and not make this an all nighter.

And it would be Americans that stole their gold. Not Jews. What numbers did they cook up? Those are official state estimates from Germany. Their gold represents only 6% of their annual GDP. Its a symbolic statement. It means almost nothing financially.

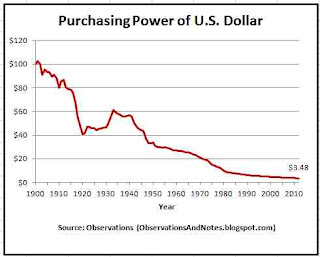

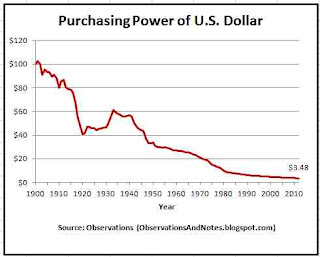

Decreasing Purchasing Power of the U.S. Dollar: What's $10,000 in 1900 Worth Today?

The graph above (click to expand) shows that if a shopper were magically transported from the year 1900 to 2012, the $100 bill that he had in his wallet in 1900 would now be worth only $3.48! That is, $100 in 2012 would have the purchasing power that $3.48 had in 1900; $10,000 would be worth only $348 today. That's a 96.4% decrease in buying power. Our shopper would consider current dollars virtually worthless. (Note: the calculations in the post were made using the inflation calculator introduced earlier this month.)

The graph above (click to expand) shows that if a shopper were magically transported from the year 1900 to 2012, the $100 bill that he had in his wallet in 1900 would now be worth only $3.48! That is, $100 in 2012 would have the purchasing power that $3.48 had in 1900; $10,000 would be worth only $348 today. That's a 96.4% decrease in buying power. Our shopper would consider current dollars virtually worthless. (Note: the calculations in the post were made using the inflation calculator introduced earlier this month.)

Domingo Halliburton

Handmade in USA

for everyone bytching about inflation read about Japan for the last 20 years

sure I simplified it. Bush and the regulators were either to dumb to see it happening or were just ignorant to it. People and banks just assumed housing prices would keep going up in perpetuity. I think ratings agencies might have been the biggest culprits.

expanding the monetary supply should happen in downturns. go buy a car or a house now and see how low interest rates are you don't think that's helping the common man? it's certainly not helping the banks.

and apparently we can't trust people anymore to make credit decisions like "can I afford this house?" regardless of how "predatory" the banks were.

Bush fired two SEC Chairman that were anti-casino, Harvey Pitt and William Donaldson. It almost seems like he wanted financial Armageddon to occur on his watch to usher in his religious beliefs.

I, Greenspan

by Bill Bonner

I, Alan Aurifericus Nefarious Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank, holder of the Medal of Freedom, Knight of the British Empire, member of the French Legion of Honor, known to my peers as the "greatest central banker who ever lived," (I will not trouble you with all my titles. I will not mention, for example, that I was the winner of the prestigious Enron Prize for distinguished public service, awarded on November 1, 2001, just days after Enron began to collapse in a heap of corruption charges) am about to give you the strange history of my later years.

For I will dispense with childhood…even with young adulthood, and those dreary sessions with that terminally dreary woman, Ayn Rand, who couldn't write a compelling sentence if her life depended on it. I'll also dispense with my own dreary years at the Council of Economic Advisors, and pass directly to the time I spent as the most powerful man in the world. For here are my real titles: Emperor of the world's most powerful money, despot of the world's largest and most dynamic economy, and architect of the most audacious financial system this sorry globe has ever seen.

Yes, I, Alan Greenspan, ruled the financial world. But who ruled Alan Greenspan? Ah…I will come to that, and tell you how, while presiding over the biggest boom ever I became caught in what I may call the "golden predicament" from which I have never since become disentangled.

This is not by any means the first thing I have written. I have written much over the years. But it was all written for a purpose, which only a few were able to discern. Most readers foolishly saw the cluttered mind of a dithering economist or the clumsy, stuttering pen of a professional bureaucrat. Many listening to my wandering speeches and twisting sentences thought that English was not my first language. They thought they detected a faint accent, like that of Henry Kissinger or Michael Caine. They mocked me as "incomprehensible" or "indecipherable." They watched what they thought was an obsequious bureaucrat squirm. They had no idea what I was really up to and what I can only now reveal.

But they admired me, too. I knew it. Because they saw in me a kind of genius…a Bernoulli of banking…a Newton of numbers…a Leibnitz of lucre…a Copernicus of currency. My mind worked at such a high pitch, they believed, that my thoughts were inaudible to most humans. They counted on me to keep the great empire's economy trundling forward. Little (actually nothing) did they know of my real thoughts and designs.

But now, all has changed. Now, I can write clearly and speak the truth. For now I am leaving my post. There is no further need for me to dissemble; no further need for me to pretend to kow-tow before Congressional committees; no further need to hide the real facts from my employers and the American people. Now, I swear by the gods, what I write comes from my own hand, and not from some overpaid, anonymous flack.

Some are born in crisis, some create crisis, and others have crisis thrust upon them.

Let me begin at the beginning. Scarcely had I settled into to the big chair at the Fed when a crisis was thrust upon me. And it is true, I responded in the conventional manner. There is no manual for central bankers, but there is a code of behavior. Faced with a financial crisis of any sort, a central banker's first duty is to run to the monetary valves and open them. This I did in 1987. I was new to the job and probably didn't open them enough. The U.S. economy lagged its rivals in Europe for several years. My old boss, George Bush, the elder, lost his bid for re-election in 1992 and blamed it on me. I resolved never to make that mistake again. Faced with a slew of challenges, shocks, uncertainties, crises and elections…ever thereafter, I made sure that every valve, throttle, level, switch and sluice gate was wide open.

But it was on December 5, 1996, that I had my first epiphany. That was the year that I made my celebrated remark about stock prices. I wondered aloud if they did not reflect a kind of "irrational exuberance." In truth, whether they did or did not, I do not know. But what I came to realize was this: 1) People, especially my employers, actually wanted prices that were irrationally exuberant. And 2) they could become far more irrationally exuberant if we put our minds to it.

I was 70 years old at the time. I had weaseled (why not be honest about it?) my way to the top post by knowing the right people and by making myself generally agreeable, and helpful, and by not saying anything anyone could disagree with. That was the original reason for what the press called "Greenspan speak." My private thoughts remained mine alone. All the public and the politicians got was gobbledygook, but for good reason.

They would not have wanted to hear what I really thought. So, I did not tell them. For I knew well and good what generally happened when politicians and central bankers got their hands on soft money and a compliant central banker. I was not born yesterday. They use their control of the money to cheat people. It is as simple as that. (I explained this early on in my career; fortunately, no one bothered to read what I wrote. Otherwise, I never would have gotten the job.) If central banking were an honest métier, there would be no reason to have it at all. Private banks could do the job better.

by Bill Bonner

I, Alan Aurifericus Nefarious Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank, holder of the Medal of Freedom, Knight of the British Empire, member of the French Legion of Honor, known to my peers as the "greatest central banker who ever lived," (I will not trouble you with all my titles. I will not mention, for example, that I was the winner of the prestigious Enron Prize for distinguished public service, awarded on November 1, 2001, just days after Enron began to collapse in a heap of corruption charges) am about to give you the strange history of my later years.

For I will dispense with childhood…even with young adulthood, and those dreary sessions with that terminally dreary woman, Ayn Rand, who couldn't write a compelling sentence if her life depended on it. I'll also dispense with my own dreary years at the Council of Economic Advisors, and pass directly to the time I spent as the most powerful man in the world. For here are my real titles: Emperor of the world's most powerful money, despot of the world's largest and most dynamic economy, and architect of the most audacious financial system this sorry globe has ever seen.

Yes, I, Alan Greenspan, ruled the financial world. But who ruled Alan Greenspan? Ah…I will come to that, and tell you how, while presiding over the biggest boom ever I became caught in what I may call the "golden predicament" from which I have never since become disentangled.

This is not by any means the first thing I have written. I have written much over the years. But it was all written for a purpose, which only a few were able to discern. Most readers foolishly saw the cluttered mind of a dithering economist or the clumsy, stuttering pen of a professional bureaucrat. Many listening to my wandering speeches and twisting sentences thought that English was not my first language. They thought they detected a faint accent, like that of Henry Kissinger or Michael Caine. They mocked me as "incomprehensible" or "indecipherable." They watched what they thought was an obsequious bureaucrat squirm. They had no idea what I was really up to and what I can only now reveal.

But they admired me, too. I knew it. Because they saw in me a kind of genius…a Bernoulli of banking…a Newton of numbers…a Leibnitz of lucre…a Copernicus of currency. My mind worked at such a high pitch, they believed, that my thoughts were inaudible to most humans. They counted on me to keep the great empire's economy trundling forward. Little (actually nothing) did they know of my real thoughts and designs.

But now, all has changed. Now, I can write clearly and speak the truth. For now I am leaving my post. There is no further need for me to dissemble; no further need for me to pretend to kow-tow before Congressional committees; no further need to hide the real facts from my employers and the American people. Now, I swear by the gods, what I write comes from my own hand, and not from some overpaid, anonymous flack.

Some are born in crisis, some create crisis, and others have crisis thrust upon them.

Let me begin at the beginning. Scarcely had I settled into to the big chair at the Fed when a crisis was thrust upon me. And it is true, I responded in the conventional manner. There is no manual for central bankers, but there is a code of behavior. Faced with a financial crisis of any sort, a central banker's first duty is to run to the monetary valves and open them. This I did in 1987. I was new to the job and probably didn't open them enough. The U.S. economy lagged its rivals in Europe for several years. My old boss, George Bush, the elder, lost his bid for re-election in 1992 and blamed it on me. I resolved never to make that mistake again. Faced with a slew of challenges, shocks, uncertainties, crises and elections…ever thereafter, I made sure that every valve, throttle, level, switch and sluice gate was wide open.

But it was on December 5, 1996, that I had my first epiphany. That was the year that I made my celebrated remark about stock prices. I wondered aloud if they did not reflect a kind of "irrational exuberance." In truth, whether they did or did not, I do not know. But what I came to realize was this: 1) People, especially my employers, actually wanted prices that were irrationally exuberant. And 2) they could become far more irrationally exuberant if we put our minds to it.

I was 70 years old at the time. I had weaseled (why not be honest about it?) my way to the top post by knowing the right people and by making myself generally agreeable, and helpful, and by not saying anything anyone could disagree with. That was the original reason for what the press called "Greenspan speak." My private thoughts remained mine alone. All the public and the politicians got was gobbledygook, but for good reason.

They would not have wanted to hear what I really thought. So, I did not tell them. For I knew well and good what generally happened when politicians and central bankers got their hands on soft money and a compliant central banker. I was not born yesterday. They use their control of the money to cheat people. It is as simple as that. (I explained this early on in my career; fortunately, no one bothered to read what I wrote. Otherwise, I never would have gotten the job.) If central banking were an honest métier, there would be no reason to have it at all. Private banks could do the job better.