Famine warning signs were clear – so why are 20 million lives now at risk?

This year could be the most deadly from famine in three decades. The lives of more than 20 million people are at

risk in four countries. Large areas of

South Sudan have already been declared a famine zone. Five years after a famine that

claimed a quarter-of-a-million lives, Somalia is back on the brink of catastrophe:

6 million people are in need of assistance. Both north-east Nigeria and Yemen face real and present risks of famine.

We are drifting slowly but with relentless predictability towards the precipice. On a conservative estimate, 1.4 million children are at imminent risk of death across the four affected countries over the next year. That number is rising by the day as hunger interacts with killer diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, cholera and measles. Every week of delayed action will put more lives on the line.

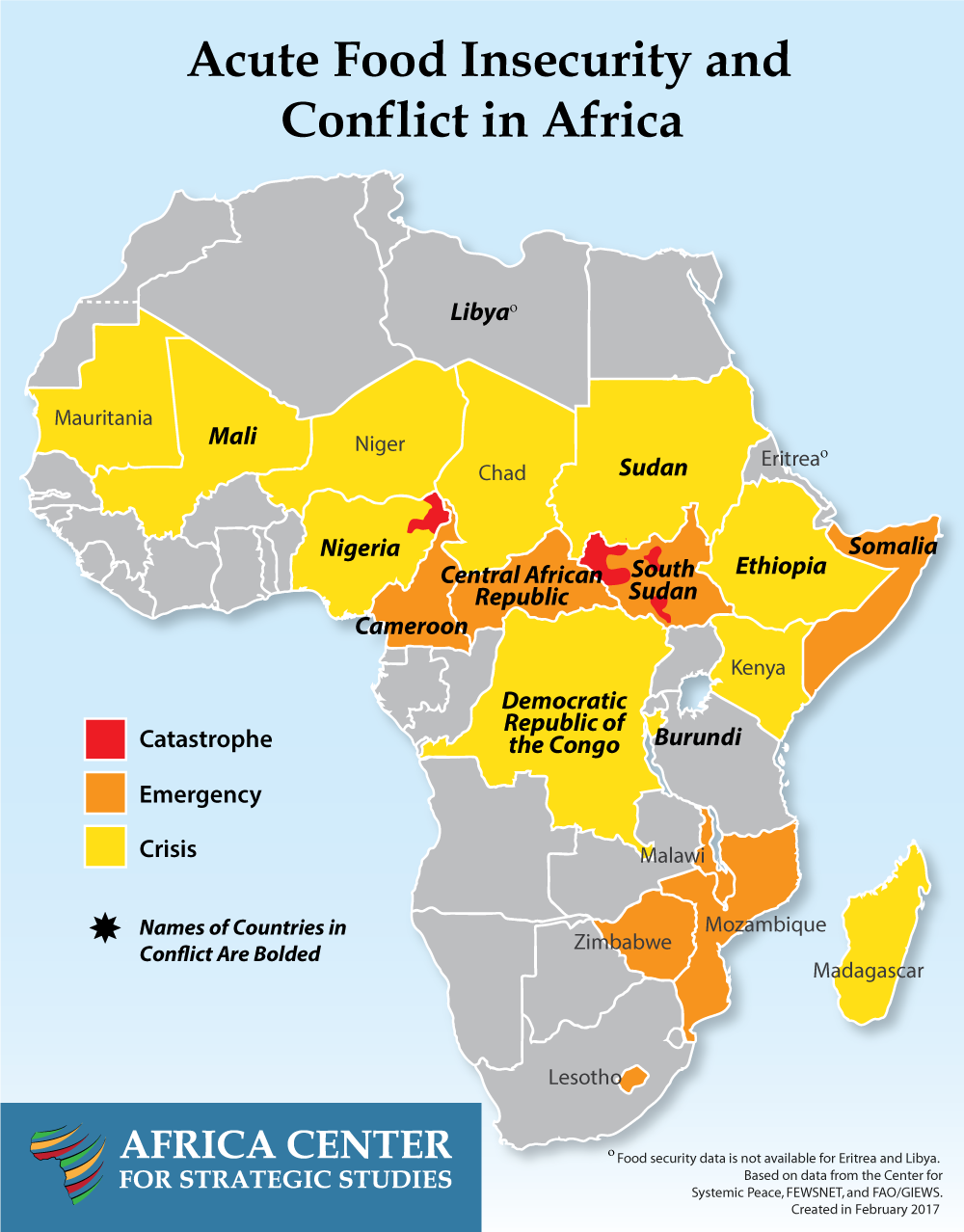

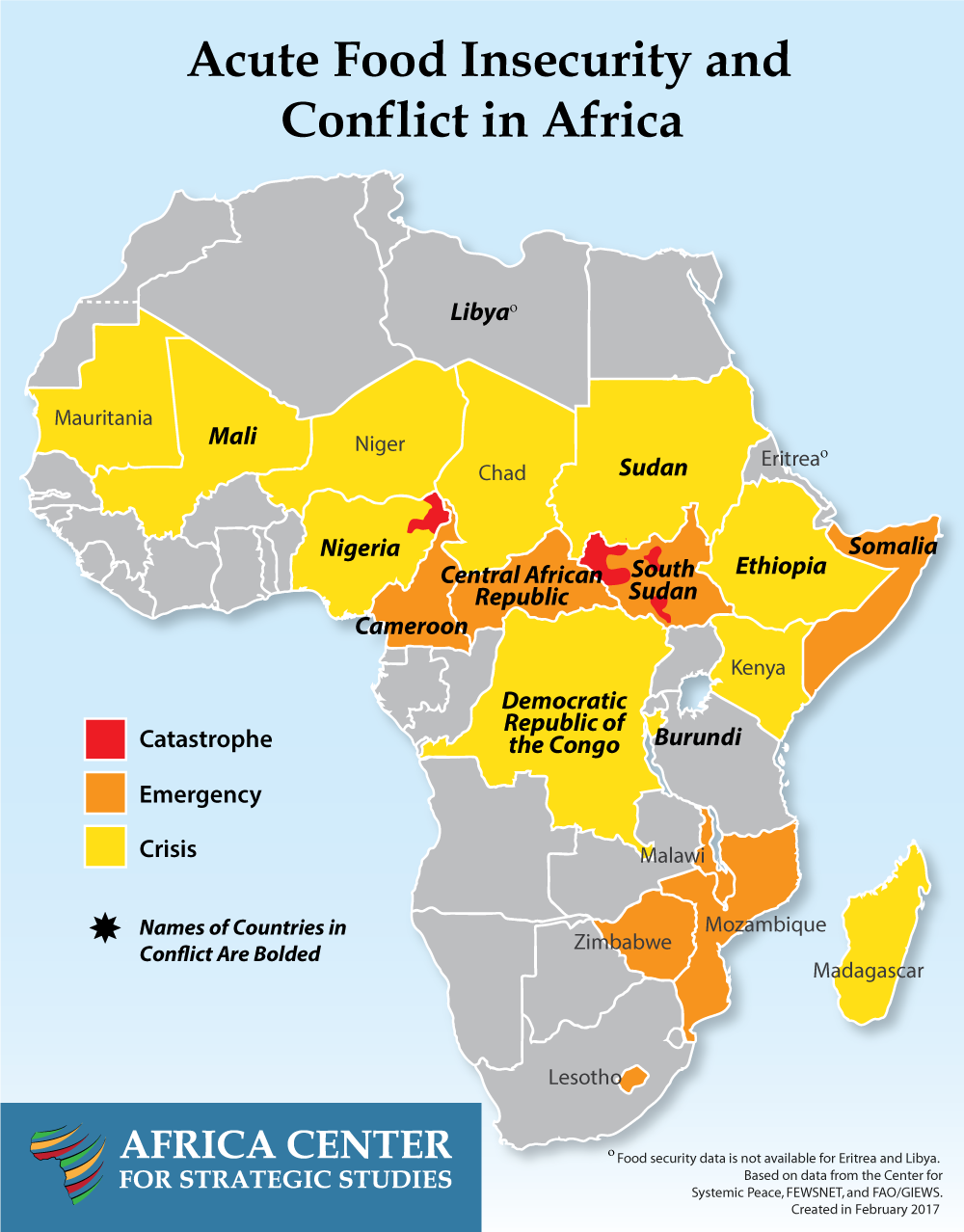

How did we get here? Conflict, drought, poor governance and a shockingly inadequate international response have all played a part.

In South Sudan, famine is concentrated in areas where government forces and rebels have been carrying out brutal ethnic killing. In Yemen, where

half a million children face severe acute malnutrition,

conflict and a humanitarian blockadeoperated by the Saudi-led coalition are pushing a food crisis towards outright famine. In northern Nigeria, the military is regaining territory from Boko Haram and uncovering

shocking levels of malnutrition. In each case, the violence is destroying livelihoods and displacing the farmers on which food production depends.

The crisis in the Horn of Africa bears all the hallmarks of the

famine declared in 2011. The region is in the third year of drought, with Somalia, southern Ethiopia and northern Kenya the worst affected. The familiar pattern of crop failure, livestock deaths and rising food prices has exposed pastoralists and farmers to acute risks and left 12.8 million in need of assistance.

All of this could have been predicted. The warning signs were clearly visible months ago. But the international community has prevaricated to the point of inertia. UN agencies that should have been working together have failed to coordinate their response, leading to fragmentation on the ground. The new UN secretary general, António Guterres, deserves credit for

sounding a loud – if belated – alarm bell. His agencies must now work together to deliver an effective response.

One consequence is a gap in financing. The UN estimates that

$5.6bn (£4.5bn) is needed to address urgent needs. Most of that money was needed yesterday. Yet less than 2% is in the financial pipeline. Aid donors have got into the bad habit of

recycling old aid pledges as new money, and failing to set clear timelines for delivery.

As the images of hunger multiply, there will be calls for action, NGOs will mount emergency appeals and there will be more pledging conferences. But surely this is the time for the major aid donors, the G7, G20 and the World Bank to convene a financing summit that provides front-loaded support, delivered through a properly coordinated system of UN agencies and NGOs?

Much of that support should be delivered in cash. Putting money in the hands of vulnerable people is far more cost-effective than delivering food. Cash transfer programmes in Somalia, Yemen and north-east

Nigeria are already protecting vulnerable people – and these programmes could be scaled-up rapidly.

Of course, money is not the only missing link. The politics of famine has to be put at the centre of the international response. Apart from being a breach of the Geneva convention, it is ethically indefensible for Saudi Arabia to obstruct humanitarian aid and bomb the ports, roads and bridges needed to deliver famine relief. It is surely time for the UK to exert its “soft-power” influence with Saudi Arabia on behalf of Yemen’s children, if necessary backed by an arms embargo and sanctions.

One age-old lesson we are re-learning from the current crisis it is that famine prevention is better than cure. Last year’s

El Niño drought in Ethiopia was one the worst since the mid-1980s, yet the country avoided a social disaster. In part, it did so because aid has been used to finance the expansions of rural health and nutrition clinics, support a safety net programme reaching 2.2 million people in the worst-affected areas, and provide relief to pastoralist communities to minimise livestock losses.

The aid cynics attacking the

UK’s commitment to spend 0.7% of national income on development assistance should take note. One of the most effective ways of saving lives is to support the efforts of poor people to build more resilient livelihoods. Britain’s aid represents a small investment with a high return in combating the poverty and building the resilience needed to prevent famine. Cutting it would hurt vulnerable people, make future famines more likely and diminish the UK’s standing as a global force for good.

Famine warning signs were clear – so why are 20 million lives now at risk? | Kevin Watkins