You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Disputed 1619 project was CORRECT, Slavery WAS key to US Revolution; Gerald Horne proved in 2014

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

Haiti, Slavery and John Stuart Mill

I'm writing another book.

Zachary D. CarterJun 3 John Stuart Mill, reading a book like a total nerd.

John Stuart Mill, reading a book like a total nerd.My next book will be a biography of John Stuart Mill. So far, I’m enjoying it very much. Mill was an unusual man who lived an extraordinary life devoted to a set of problems that once again dominate political thought in the 21st century.

I try to be cautious about describing a long-term project like a book early on, because whatever you think you're writing at the outset is inevitably transformed by what you learn along the way. When I pitched my proposal for The Price of Peace, I wasn't planning to spend a whole lot of time on Keynes in the interwar years. But of course that plan was ridiculous and I abandoned it as soon as I encountered a letter Keynes wrote in 1923 about getting lost in the countryside on a fox hunt gone haywire. I don't expect much on foxhunting for the Mill book — it will be about the things I find most interesting, namely liberalism, democracy, war, and sex — but beyond that, it’s still hard to say.

Last month, however, the New York Times published an extraordinary series on the economic and political history of Haiti (including a 5,400-word piece detailing the paper’s research methods and sources). And this week, I came across some writing from Mill on Haiti that I think helps illuminate the way early 19th century thinkers understood some of the events in the Times series. It’s too interesting to keep to myself until the book comes out, so I’ll share it here.

In 1824, a new publication called the Westminster Review enlisted Mill to write an essay blasting the hell out of a rival publication called the Edinburgh Review. In the essay, Mill essentially called the Edinburgh editors a bunch of rich sellouts who were too selfish to think straight. His most damning piece of evidence was an Edinburgh article that had defended France’s claims on Haiti. The Edinburgh, Mill noted with palpable disgust, had implored the people of Britain to support France against the Haitian Revolution, on the grounds that a new, self-governing Black nation would be dangerous to nearby British colonies. Mill really let the Edinburgh have it, but what I find most interesting about his attack is his evident disinterest in making a detailed argument. The persuasive force of his rhetoric comes from simply restating the Edinburgh's position and declaring (correctly) that it is morally horrendous. The great Edinburgh Review, Mill jeered, had been ready to condemn an entire nation "to the alternative of death, or of the most horrible slavery" in order to protect the profits of a few plantation owners.

Do you even lift, bro?

Do you even lift, bro?This tells us at least four important things about the intellectual climate of the early 19th century. First, there were people who regarded what France was doing to Haiti as a great crime, and said so. Second, for a substantial population, merely reciting what France had done to Haiti was enough to generate moral outrage. You didn't have to explain to this crowd that it was wrong to enslave human beings, or that it was wrong to fight wars in defense of slavery. They knew.

Third, there was a very detailed spectrum of opinion in 19th century Europe on human rights. Even Mill’s targets at the Edinburgh explicitly acknowledged “the unmerited sufferings of the unhappy negroes” in Haiti — they simply denied that righting those wrongs trumped the commercial interests of British colonists. In the United States, we’re accustomed to thinking about the slavery question as a pro-con dichotomy, a habit encouraged by a very bloody Civil War that was fought to end “the peculiar institution.” But there were many different ways to “oppose” slavery. There were reformers who wanted to pay off enslavers, reformers who wanted to imprison enslavers, and reformers who only had a problem with slavery when it was carried out by other empires. Functionally, this meant that a great many people could applaud themselves as broad-minded humanitarians, while also esteeming political “moderation” that bent public policy to the benefit of those who profited from slavery.

Fourth, and perhaps most important, Mill’s missive helps demonstrate the political limits of intellectual discourse in the early Liberal era. Some of the most famous minds in Europe decried the plundering of Haiti, and it was plundered anyway, and then plundered again, and again. Not because nobody knew any better, or because plundering was inevitable, but because people with power really wanted to do it.

There’s much more that could be said, of course, but that’s what the book is for. I’ll leave you with Mill:

The other article to which we alluded presents a remarkable contrast with the tone which the Edinburgh Review afterwards assumed, on the subject of negro slavery. Its object is, to prove that we ought to wish success to an armament which the French government was then fitting out against Hayti; and that we ought even, if necessary, to assist the French in their enterprise. When we consider what that enterprise was -- an enterprise for the purpose of reducing a whole nation of negroes to the alternative of death, or of the most horrible slavery; and when we consider upon what ground we are directed to co-operate in it, namely, the danger to which our colonies would be exposed, by the existence of an independent negro commonwealth, we can have no difficulty in appreciating such language as the following:

We have the greatest sympathy for the unmerited sufferings of the unhappy negroes; we detest the odious traffic which has poured their myriads into the Antilles; but we must be permitted some tenderness for our European brethren, although they are white and civilized, and to deprecate that inconsistent spirit of canting philanthropy which, in Europe, is only excited by the wrongs or miseries of the poor and the profligate, and, on the other side of the Atlantic, is never warmed but towards the savage, the mulatto, and the slave.

To couple together "the poor" and "the profligate," as if they were two names for the same thing, is a piece of complaisance to aristocratic morality which requires no comment. Then all who venture to doubt whether it is perfectly just and human to aid in reducing one half of the people of Hayti to slavery and exterminating the other half, are accused of sympathizing exclusively with the blacks. We wonder what the writer would call sympathizing exclusively with the whites. We should have thought that the lives and liberties of a whole nation, were an ample sacrifice, for the sake of a slight, or rather, as the event has proven, an imaginary addition to the security of the property of a few West-India planters. This is, indeed, to abjure "canting philanthropy." What it is that the reviewer gives us in the place of it we leave the reader to judge.

Subscribe to In The Long Run

By Zachary D. Carter · Launched a year agoA newsletter about everything that really matters: Money, politics, power and dogs.

Tory's in the UK basically have the same opinion as the 1619 project

What’s Actually Being Taught in History Class

Schools across the country have been caught up in spirited debates over what students should learn about United States history. We talked to seven social studies teachers about how they run their classrooms, what they teach and why.

www.nytimes.com

Opinion | The Idea That Letting Trump Walk Will Heal America Is Ridiculous

If a president can get away with an attempted coup (as well as abscond with classified documents), then there’s nothing he can’t do.

The Idea That Letting Trump Walk Will Heal America Is Ridiculous

Aug. 23, 2022

Scott Olson/Getty Images

The main argument against prosecuting Donald Trump — or investigating him with an eye toward criminal prosecution — is that it will worsen an already volatile fracture in American society between Republicans and Democrats. If, before an indictment, we could contain the forces of political chaos and social dissolution, the argument goes, then in the aftermath of such a move, we would be at their mercy. American democracy might not survive the stress.

All of this might sound persuasive to a certain, risk-averse cast of mind. But it rests on two assumptions that can’t support the weight that’s been put on them.

The first is the idea that American politics has, with Trump’s departure from the White House, returned to a kind of normalcy. Under this view, a prosecution would be an extreme and irrevocable blow to social peace. But the absence of open conflict is not the same as peace. Voters may have put a relic of the 1990s into the Oval Office, but the status quo of American politics is far from where it was before Trump.

The most important of our new realities is the fact that much of the Republican Party has turned itself against electoral democracy. The Republican nominee for governor in Arizona — Kari Lake — is a 2020 presidential election denier. So, too, are the Republican nominees in Arizona for secretary of state, state attorney general and U.S. Senate. In Pennsylvania, Republican voters overwhelmingly chose the pro-insurrection Doug Mastriano to lead their party’s ticket in November. Overall, Republican voters have nominated election deniers in dozens of races across six swing states, including candidates for top offices in Georgia, Nevada and Wisconsin.

There is also something to learn from the much-obsessed-over fate of Liz Cheney, the arch-conservative representative from Wyoming, who lost her placeon the Republican ticket on account of her opposition to the movement to “stop the steal” and her leadership on the House Jan. 6 committee investigating Trump’s attempt to overturn the presidential election to keep himself in office. Cheney is, on every other issue of substance, with the right wing of the Republican Party. But she opposed the insurrection and accepted the results of the 2020 presidential election. It was, for Wyoming voters, a bridge too far.

All of this is to say that we are already in a place where a substantial portion of the country (although much less than half) has aligned itself against the basic principles of American democracy in favor of Trump. And these 2020 deniers aren’t sitting still, either; as these election results show, they are actively working to undermine democracy for the next time Trump is on the ballot.

This fact, alone, makes a mockery of the idea that the ultimate remedy for Trump is to beat him at the ballot box a second time, as if the same supporters who rejected the last election will change course in the face of another defeat. It also makes clear the other weight-bearing problem with the argument against holding Trump accountable, which is that it treats inaction as an apolitical and stability-enhancing move — something that preserves the status quo as opposed to action, which upends it.

But that’s not true. Inaction is as much a political choice as action is, and far from preserving the status quo — or securing some level of social peace — it sets in stone a new world of total impunity for any sufficiently popular politician or member of the political elite.

Now, it is true that political elites in this country are already immune to most meaningful consequences for corruption and lawbreaking. But showing forbearance and magnanimity toward Trump and his allies would take a difficult problem and make it irreparable. If a president can get away with an attempted coup (as well as abscond with classified documents), then there’s nothing he can’t do. He is, for all intents and purposes, above the law.

Among skeptics of prosecution, there appears to be a belief that restraint would create a stable equilibrium between the two parties; that if Democrats decline to pursue Trump, then Republicans will return the favor when they win office again. But this is foolish to the point of delusion. We don’t even have to look to the recent history of Republican politicians using the tools of office to investigate their political opponents. We only have to look to the consequences of giving Trump (or any of his would-be successors) a grant of nearly unaccountable power. Why would he restrain himself in 2025 or beyond? Why wouldn’t he and his allies use the tools of state to target the opposition?

The arguments against prosecuting Trump don’t just ignore or discount the current state of the Republican Party and the actually existing status quo in the United States, they also ignore the crucial fact that this country has experience with exactly this kind of surrender in the face of political criminality.

National politics in the 1870s was consumed with the question of how much to respond to vigilante lawlessness, discrimination and political violence in the postwar South. Northern opponents of federal and congressional intervention made familiar arguments.

If Republicans, The New York Times argued in 1874, “set aside the necessity of direct authority from the Constitution” to pursue their aims in the South and elsewhere, could they then “expect the Democrats, if they should gain the power, to let the Constitution prevent them from helping their ancient and present friends?”

The better approach, The Times said in an earlier editorial, was to let time do its work. “The law has clothed the colored man with all the attributes of citizenship. It has secured him equality before the law, and invested him with the ballot.” But here, wrote the editors, “the province of law will end. All else must be left to the operation of causes more potent than law, and wholly beyond its reach.” His old oppressors in the South, they added, “rest their only hope of party success upon their ability to obtain his goodwill.”

To act affirmatively would create unrest. Instead, the country should let politics and time do their work. The problems would resolve themselves, and Americans would enjoy a measure of social peace as a result.

Of course, that is not what happened. In the face of lawlessness, inaction led to impunity, and impunity led to a successful movement to turn back the clock on progress as far as possible, by any means possible.

Our experience, as Americans, tells us that there is a clear point at which we must act in the face of corruption, lawlessness and contempt for the very foundations of democratic society. The only way out is through. Fear of what Trump and his supporters might do cannot and should not stand in the way of what we must do to secure the Constitution from all its enemies, foreign and domestic.

Jamelle Bouie became a New York Times Opinion columnist in 2019. Before that he was the chief political correspondent for Slate magazine. He is based in Charlottesville, Va., and Washington. @jbouie

Black History and "Presentism" - Lawyers, Guns & Money

The idiot president of the American Historical Association, James Sweet, permanently destroyed his reputation in much of the profession through his ill-thought out essay on “presentism,” in which he didn’t do anything even close to providing a historical argument with evidence, only cited the...

www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com

Black Historians Know There’s No Such Thing as Objective History

Recent critiques of “presentism” fail to see that we can’t divorce the past from the present—and that supposedly objective scholarship has long promoted racist narratives and suppressed Black history.

Black Historians Know There’s No Such Thing as Objective History

Recent critiques of “presentism” fail to see that we can’t divorce the past from the present—and that supposedly objective scholarship has long promoted racist narratives and suppressed Black history.

Keisha N. BlainSeptember 9, 2022

In Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro, writer James Baldwin observes, “History is not the past. History is the present. We carry our history with us. To think otherwise is criminal.” Baldwin’s remarks succinctly capture our relationship to the past. They also address the role of “presentism”—the use of a present lens to interpret the past—within the historical profession.

Historians often use the term “presentism” as a critique—to cast doubt on the objectivity of scholarship from those who consider the present in their analyses of the past. Scholars who resist “presentism” will argue that it somehow distorts the historical narrative. According to this thinking, one should never consider present circumstances when interpreting developments of the past—or when trying to understand figures from the past. To do so is to defy the very essence of the profession, one supposedly based on neutrality.

James H. Sweet, president of the American Historical Association, certainly seems to think so. In an essay titled “Is History History?” in the September issue of Perspectives, the AHA’s monthly magazine, he bemoaned a “trend toward presentism” in historical analysis, rhetorically asking, “If we don’t read the past through the prism of contemporary social justice issues—race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, capitalism—are we doing history that matters?” He later added, “If history is only those stories from the past that confirm current political positions, all manner of political hacks can claim historical expertise. Too many Americans have become accustomed to the idea of history as an evidentiary grab bag to articulate their political positions.”

Sweet’s critique ignited a broad debate about the role of the present in historical analyses. The backlash prompted Sweet to append an apology to his essay, which some on the right saw as caving to the “woke mob.” But as a Black historian who understands the power of my writing and research, there is little to debate. Black historians have long recognized the role of the present in shaping our narratives of the past. We have never had the luxury of writing about the past as though it were divorced from present concerns. The persistence of racism, white supremacy, and racial inequality everywhere in American society makes it impossible to do so.

Historians, like anyone else, exist in the present, and our work will always reflect contemporary realities—explicitly or implicitly. Contrary to popular belief, there is no standard or “neutral” interpretation of the past. The typical standard historical account of the United States, for example, is often distorted into narratives that deemphasize the contributions of people of color and uphold racial stereotypes. This was intentional. Consider the work of historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, widely recognized in his lifetime as one of the most influential historians of the South. His 1918 book, American Negro Slavery, was widely read and cited. Yet it offered no “objective” historical analysis. To the contrary, the book only served to perpetuate racist stereotypes about African Americans, and it helped to reinforce segregation and exclusionary laws in the U.S.

Black historians worked to challenge these kinds of accounts during the 1920s. Anna Julia Cooper’s 1924 dissertation in the field of history at the Sorbonne University in Paris directly condemned the institution of slavery. As European nations maintained colonial rule, exploiting millions of people of color across the globe, Cooper wielded her scholarship as a weapon to challenge the global color line.

Carter G. Woodson, founder of Black History Month and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, responded similarly. By establishing “Negro History Week” in February 1926—which would later become Black History Month—Woodson disrupted educational norms in the U.S. shaped by white supremacy and anti-Blackness. “The so-called modern education, with all its defects,” he explained in his provocative 1933 book The Miseducation of the Negro, “does others so much more good than it does the Negro, because it has been worked out in conformity to the needs of those who have enslaved and oppressed weaker peoples.” Societal change is impossible, Woodson argued, when we fail to interrogate the standard accounts of history and other fields of study. Telling “neutral” historical accounts of egregious practices such as slavery and lynching serves a fundamental purpose—to excuse injustices of the present and thereby maintain systems of oppression. It is a form of purposeful amnesia designed to empower oppressors.

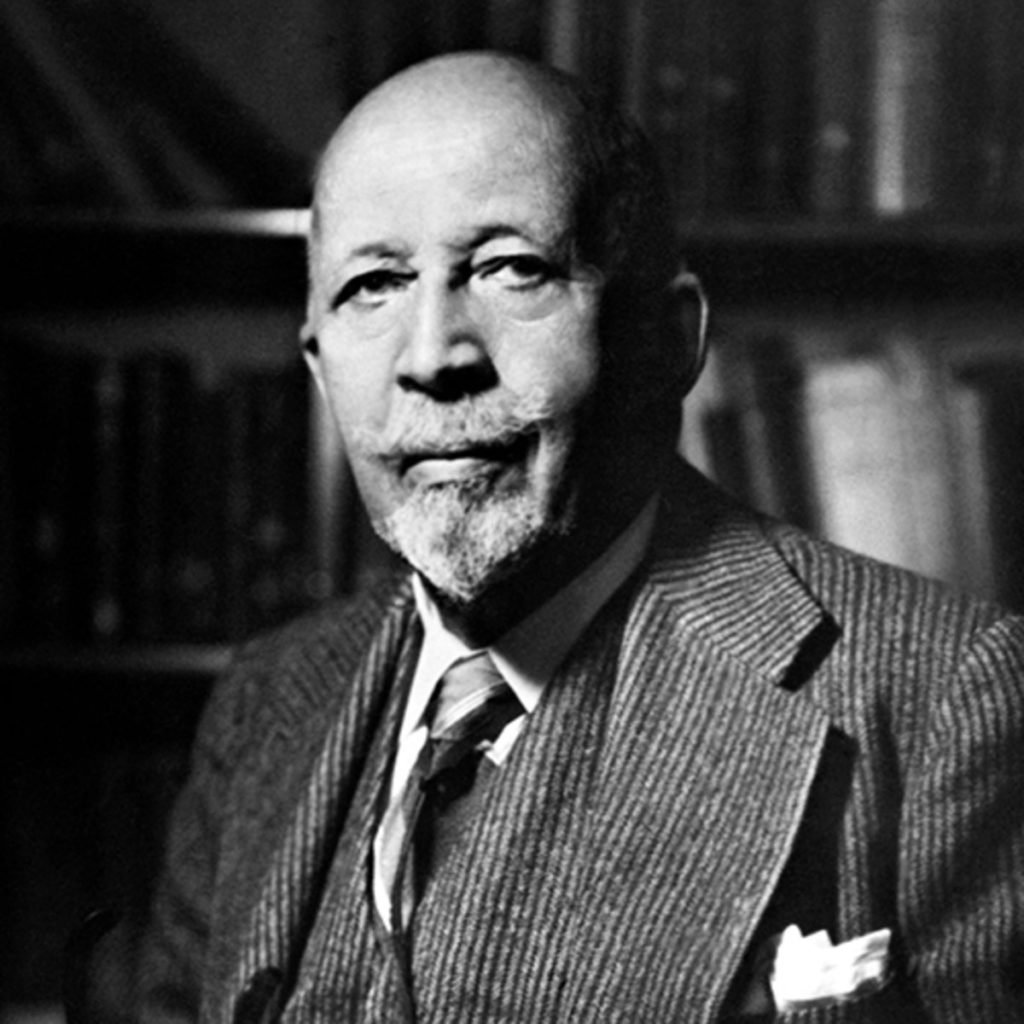

Historian W.E.B. Du Bois also made this observation in his 1935 magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America. His final chapter, “The Propaganda of History,” confronted the many lies that “objective” historians were peddling at the time about the history of Reconstruction. His pioneering book, published against the backdrop of a surge of Black radical movements of the Great Depression, directly refuted the false narratives emerging from leading white scholars of the Dunning School (named after William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University). In their portrayal of Reconstruction, the Dunning School scholars, as Du Bois explained, had portrayed the South as victims and the North as having committed a “grievous wrong.” Their writings on the subject treated the free and enslaved Black population with “ridicule, contempt or silence.” They also peddled racial stereotypes and mischaracterizations of Black intellectual ability.

The Dunning School’s interpretation of the past was very much shaped by present concerns at the time. They used their writings on the past to justify—and give moral validity to—the mistreatment of African Americans. The scholarship of these historians served to reinforce segregation and racial discrimination in the U.S. during the early twentieth century. White policymakers, educators, and others cited the racist interpretations of the Dunning School to further limit Black access in the public sphere and to uphold stereotypes. The same scholars decrying “presentism” today most likely would have framed Du Bois’s powerful rebuttal in the same manner—as some of his critics did. But were it not for scholars like Du Bois, we would still be relying on the white establishment’s racist accounts of Reconstruction.

Du Bois’s response to the Dunning School, as well as the efforts of Anna Julia Cooper and Carter G. Woodson, exemplify how Black historians have taken an active role in confronting political abuses of the past. They were not alone. Marion Thompson Wright, Dorothy Porter Wesley, and Merze Tate were among the first generation of professional Black historians who used their writing and research of the past to address myriad contemporary social issues. They recognized, as Manning Marable, the founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University, observed in 1998, that “scholarship and social struggle cannot be separated.”

Indeed, historians do not produce scholarship in isolation. The work we do has the potential to shape national debates and inform policies that have broad implications for all Americans. The weight of this responsibility is especially great for members of marginalized groups. In a white-dominated world and academy, we are always fighting to assert our voices and our histories into spaces designed to exclude us.

More importantly, we are fighting for our lives. The commitment to engaging present concerns is not simply a method or approach to the scholar’s craft of research and writing. It is a matter of life and death. The reality of the present moment propels many of us to act. In the spirit of Du Bois, Woodson, Cooper, and others, we have a duty to lend our expertise to the most pressing issues of our day. It is not only logical and responsible to do so; it fulfills the underlying mission of historical study in communities of color to illuminate the complexity of our lived experiences.