You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Disputed 1619 project was CORRECT, Slavery WAS key to US Revolution; Gerald Horne proved in 2014

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Fun fact. Gerald Horne's book is how I found The Coli.

How so?

nytimes.com

Opinion | Did a Fear of Slave Revolts Drive American Independence?

Robert G. Parkinson

6-7 minutes

Op-Ed Contributor

Credit...George Bates

Binghamton, N.Y. — FOR more than two centuries, we have been reading the Declaration of Independence wrong. Or rather, we’ve been celebrating the Declaration as people in the 19th and 20th centuries have told us we should, but not the Declaration as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams wrote it. To them, separation from Britain was as much, if not more, about racial fear and exclusion as it was about inalienable rights.

The Declaration’s beautiful preamble distracts us from the heart of the document, the 27 accusations against King George III over which its authors wrangled and debated, trying to get the wording just right. The very last one — the ultimate deal-breaker — was the most important for them, and it is for us: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” In the context of the 18th century, “domestic insurrections” refers to rebellious slaves. “Merciless Indian savages” doesn’t need much explanation.

In fact, Jefferson had originally included an extended attack on the king for forcing slavery upon unwitting colonists. Had it stood, it would have been the patriots’ most powerful critique of slavery. The Continental Congress cut out all references to slavery as “piratical warfare” and an “assemblage of horrors,” and left only the sentiment that King George was “now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us.” The Declaration could have been what we yearn for it to be, a statement of universal rights, but it wasn’t. What became the official version was one marked by division.

Upon hearing the news that the Congress had just declared American independence, a group of people gathered in the tiny village of Huntington, N.Y., to observe the occasion by creating an effigy of King George. But before torching the tyrant, the Long Islanders did something odd, at least to us. According to a report in a New York City newspaper, first they blackened his face, and then, alongside his wooden crown, they stuck his head “full of feathers” like “savages,” wrapped his body in the Union Jack, lined it with gunpowder and then set it ablaze.

The 27th and final grievance was at the Declaration’s heart (and on Long Islanders’ minds) because in the 15 months between the Battles of Lexington and Concord and independence, reports about the role African-Americans and Indians would play in the coming conflict was the most widely discussed news. And British officials all over North America did seek the aid of slaves and Indians to quell the rebellion.

A few months before Jefferson wrote the Declaration, the Continental Congress received a letter from an army commander that contained a shocking revelation: Two British officials, Guy Carleton and Guy Johnson, had gathered a number of Indians and begged them to “feast on a Bostonian and drink his blood.” Seizing this as proof that the British were utterly despicable, Congress ordered this letter printed in newspapers from Massachusetts to Virginia.

At the same time, patriot leaders had publicized so many notices attacking the November 1775 emancipation proclamation by the governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, that, by year’s end, a Philadelphia newspaper reported a striking encounter on that city’s streets. A white woman was appalled when an African-American man refused to make way for her on the sidewalk, to which he responded, “Stay, you damned white bytch, till Lord Dunmore and his black regiment come, and then we will see who is to take the wall.”

His expectation, that redemption day was imminent, shows how much those sponsored newspaper articles had soaked into everyday conversation. Adams, Franklin and Jefferson were essential in broadcasting these accounts as loudly as they could. They highlighted any efforts of British agents like Dunmore, Carleton and Johnson to involve African-Americans and Indians in defeating the Revolution.

Even though the black Philadelphian saw this as wonderful news, the founders intended those stories to stoke American outrage. It was a very rare week in 1775 and 1776 in which Americans would open their local paper without reading at least one article about British officials “whispering” to Indians or “tampering” with slave plantations.

So when the crowd in Huntington blackened the effigy’s face and stuffed its head with feathers before setting it on fire, they were indeed celebrating an independent America, but one defined by racial fear and exclusion. Their burning of the king and his enslaved and native supporters together signified the opposite of what we think of as America. The effigy represented a collection of enemies who were all excluded from the republic born on July 4, 1776.

This idea — that some people belong as proper Americans and others do not — has marked American history ever since. We like to excuse the founders from this, to give them a pass. After all, there is that bit about everyone being “created equal” in this, the most important text of American history and identity. And George Washington’s army was the most racially integrated army the United States would field until Vietnam, much to Washington’s chagrin.

But you wouldn’t know that from reading the newspapers. All the African-Americans and Indians who supported the revolution — and lots did — were no match against the idea that they were all “merciless savages” and “domestic insurrectionists.” Like the people of Huntington, Americans since 1776 have operated time and time again on the assumption that blacks and Indians don’t belong in this republic. This notion comes from the very founders we revere this weekend. It haunts us still.

Opinion | Did a Fear of Slave Revolts Drive American Independence?

Robert G. Parkinson

6-7 minutes

Op-Ed Contributor

- July 4, 2016

Credit...George Bates

Binghamton, N.Y. — FOR more than two centuries, we have been reading the Declaration of Independence wrong. Or rather, we’ve been celebrating the Declaration as people in the 19th and 20th centuries have told us we should, but not the Declaration as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams wrote it. To them, separation from Britain was as much, if not more, about racial fear and exclusion as it was about inalienable rights.

The Declaration’s beautiful preamble distracts us from the heart of the document, the 27 accusations against King George III over which its authors wrangled and debated, trying to get the wording just right. The very last one — the ultimate deal-breaker — was the most important for them, and it is for us: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” In the context of the 18th century, “domestic insurrections” refers to rebellious slaves. “Merciless Indian savages” doesn’t need much explanation.

In fact, Jefferson had originally included an extended attack on the king for forcing slavery upon unwitting colonists. Had it stood, it would have been the patriots’ most powerful critique of slavery. The Continental Congress cut out all references to slavery as “piratical warfare” and an “assemblage of horrors,” and left only the sentiment that King George was “now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us.” The Declaration could have been what we yearn for it to be, a statement of universal rights, but it wasn’t. What became the official version was one marked by division.

Upon hearing the news that the Congress had just declared American independence, a group of people gathered in the tiny village of Huntington, N.Y., to observe the occasion by creating an effigy of King George. But before torching the tyrant, the Long Islanders did something odd, at least to us. According to a report in a New York City newspaper, first they blackened his face, and then, alongside his wooden crown, they stuck his head “full of feathers” like “savages,” wrapped his body in the Union Jack, lined it with gunpowder and then set it ablaze.

The 27th and final grievance was at the Declaration’s heart (and on Long Islanders’ minds) because in the 15 months between the Battles of Lexington and Concord and independence, reports about the role African-Americans and Indians would play in the coming conflict was the most widely discussed news. And British officials all over North America did seek the aid of slaves and Indians to quell the rebellion.

A few months before Jefferson wrote the Declaration, the Continental Congress received a letter from an army commander that contained a shocking revelation: Two British officials, Guy Carleton and Guy Johnson, had gathered a number of Indians and begged them to “feast on a Bostonian and drink his blood.” Seizing this as proof that the British were utterly despicable, Congress ordered this letter printed in newspapers from Massachusetts to Virginia.

At the same time, patriot leaders had publicized so many notices attacking the November 1775 emancipation proclamation by the governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, that, by year’s end, a Philadelphia newspaper reported a striking encounter on that city’s streets. A white woman was appalled when an African-American man refused to make way for her on the sidewalk, to which he responded, “Stay, you damned white bytch, till Lord Dunmore and his black regiment come, and then we will see who is to take the wall.”

His expectation, that redemption day was imminent, shows how much those sponsored newspaper articles had soaked into everyday conversation. Adams, Franklin and Jefferson were essential in broadcasting these accounts as loudly as they could. They highlighted any efforts of British agents like Dunmore, Carleton and Johnson to involve African-Americans and Indians in defeating the Revolution.

Even though the black Philadelphian saw this as wonderful news, the founders intended those stories to stoke American outrage. It was a very rare week in 1775 and 1776 in which Americans would open their local paper without reading at least one article about British officials “whispering” to Indians or “tampering” with slave plantations.

So when the crowd in Huntington blackened the effigy’s face and stuffed its head with feathers before setting it on fire, they were indeed celebrating an independent America, but one defined by racial fear and exclusion. Their burning of the king and his enslaved and native supporters together signified the opposite of what we think of as America. The effigy represented a collection of enemies who were all excluded from the republic born on July 4, 1776.

This idea — that some people belong as proper Americans and others do not — has marked American history ever since. We like to excuse the founders from this, to give them a pass. After all, there is that bit about everyone being “created equal” in this, the most important text of American history and identity. And George Washington’s army was the most racially integrated army the United States would field until Vietnam, much to Washington’s chagrin.

But you wouldn’t know that from reading the newspapers. All the African-Americans and Indians who supported the revolution — and lots did — were no match against the idea that they were all “merciless savages” and “domestic insurrectionists.” Like the people of Huntington, Americans since 1776 have operated time and time again on the assumption that blacks and Indians don’t belong in this republic. This notion comes from the very founders we revere this weekend. It haunts us still.

Last edited:

Abigail Adams

Abigail AdamsEvidence Detail :: U.S. History

I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore.

I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. . . .

Abigail Adams knew that shyt was wrong...

Abigail adams again...

theatlantic.com

How Abigail Adams Proves Bill O'Reilly Wrong About Slavery

David A. Graham

8-10 minutes

The Fox host’s insistence that black laborers building the White House were “well-fed and had decent lodgings” fits in a long history of insisting the “peculiar institution” wasn’t so bad.

July 27, 2016

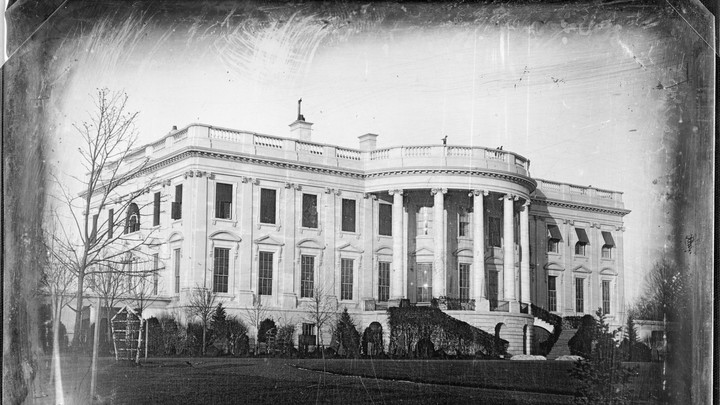

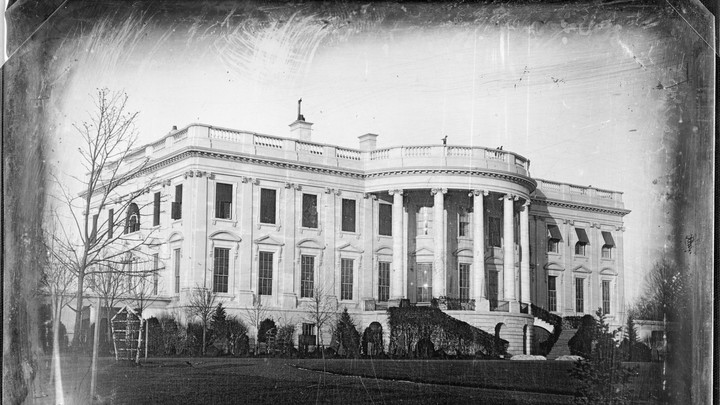

The White House in 1846Library of Congress

In her widely lauded speech at the Democratic National Convention on Monday, Michelle Obama reflected on the remarkable fact of her African American family living in the executive mansion. “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves. And I watch my daughters, two beautiful, intelligent, black young women, playing with their dogs on the White House lawn,” she said.

On Tuesday, Fox News host Bill O’Reilly discussed the moment in his Tip of the Day. In a moment first noticed by the liberal press-tracking group Media Matters, O’Reilly said this:

As we mentioned, Talking Points Memo, Michelle Obama referenced slaves building the White House in referring to the evolution of America in a positive way. It was a positive comment. The history behind her remark is fascinating. George Washington selected the site in 1791, and as president laid the cornerstone in 1792. Washington was then running the country out of Philadelphia.

Slaves did participate in the construction of the White House. Records show about 400 payments made to slave masters between 1795 and 1801. In addition, free blacks, whites, and immigrants also worked on the massive building. There were no illegal immigrants at that time. If you could make it here, you could stay here.

In 1800, President John Adams took up residence in what was then called the Executive Mansion. It was only later on they named it the White House. But Adams was in there with Abigail, and they were still hammering nails, the construction was still going on.

Slaves that worked there were well-fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government, which stopped hiring slave labor in 1802. However, the feds did not forbid subcontractors from using slave labor. So, Michelle Obama is essentially correct in citing slaves as builders of the White House, but there were others working as well. Got it all? There will be a quiz.

O’Reilly’s comments were a small line at the end of the show, so one shouldn’t make too much of them. But the riff is notable for the way it resuscitates two common threads of apology for slavery: First, that human bondage didn’t play as large a role in American history as its critics might have you believe; and second, that it wasn’t as bad as they’d have you believe, either.

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading

Obama’s invocation of the slaves who built the White House was rhetorically powerful because the building is a symbol of the United States; to say slaves built it is to imply that they built the United States. Pointing out that it was not only slaves who built it (in essence, debunking an assertion that Obama did not make) undercuts the point, and in turn connects to the long tradition of arguing that however bad slavery may have been, it was only a small, regional phenomenon in the South. But as my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates has written, slavery was the engine of the entire antebellum American economy: “In the seven cotton states, one-third of all white income was derived from slavery. By 1840, cotton produced by slave labor constituted 59 percent of the country’s exports.” Coates quotes historian David Blight, who wrote, “Slaves were the single largest, by far, financial asset of property in the entire American economy.”

More immediately controversial was O’Reilly’s statement that slaves working at the White House “were well-fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government.” The idea that slavery was, if not a good thing, not such a bad thing overall has a long, if hardly venerable, intellectual history.

This defense of slavery as essentially benign runs, for example, through Senator John C. Calhoun’s 1837 speech defending the “peculiar institution” from the criticism of northerners. In a speech in which he labeled slavery “a positive good,” the South Carolinian contended that enslaved blacks actually had it good:

Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse.

Some 20 years later, another senator from South Carolina, James Henry Hammond, made the same point. Speaking to Northerners, he contended:

The difference between us is, that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated; there is no starvation, no begging, no want of employment among our people, and not too much employment either. Yours are hired by the day, not cared for, and scantily compensated, which may be proved in the most painful manner, at any hour in any street in any of your large towns. Why, you meet more beggars in one day, in any single street of the city of New York, than you would meet in a lifetime in the whole South.

Of course, that wasn’t quite all of it. Hammond added that the manifest inferiority of blacks further not only justified but practically sanctified the endeavor:

We do not think that whites should be slaves either by law or necessity. Our slaves are black, of another and inferior race. The status in which we have placed them is an elevation. They are elevated from the condition in which God first created them, by being made our slaves. None of that race on the whole face of the globe can be compared with the slaves of the South. They are happy, content, uninspiring, and utterly incapable, from intellectual weakness, ever to give us any trouble by their aspirations.

It is not hard to find contemporary accounts from slaves who were neither happy nor content—and whose eloquent testimony accounts to their inspiration, capability, and intellectual powers. If many whites like Hammond were unable to see this, however, others were not so blinkered. As O’Reilly noted, Michelle Obama’s predecessor as first lady, Abigail Adams was living in the White House at the time when slaves were building it, and she recorded her observations of those working on landscaping the grounds.

“The effects of Slavery are visible every where; and I have amused myself from day to day in looking at the labour of 12 negroes from my window, who are employd with four small Horse Carts to remove some dirt in front of the house,” she wrote. Moreover, Mrs. Adams took note of their condition—and her observation stands at odds with O’Reilly’s:

Two of our hardy N England men would do as much work in a day as the whole 12, but it is true Republicanism that drive the Slaves half fed, and destitute of cloathing, ... to labour, whilst the owner waches about Idle, tho his one Slave is all the property he can boast.

Adams’s rebuke to O’Reilly is not the first time that a benign recollection of slavery has broken apart on the shoals of reality.

theatlantic.com

How Abigail Adams Proves Bill O'Reilly Wrong About Slavery

David A. Graham

8-10 minutes

The Fox host’s insistence that black laborers building the White House were “well-fed and had decent lodgings” fits in a long history of insisting the “peculiar institution” wasn’t so bad.

July 27, 2016

The White House in 1846Library of Congress

In her widely lauded speech at the Democratic National Convention on Monday, Michelle Obama reflected on the remarkable fact of her African American family living in the executive mansion. “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves. And I watch my daughters, two beautiful, intelligent, black young women, playing with their dogs on the White House lawn,” she said.

On Tuesday, Fox News host Bill O’Reilly discussed the moment in his Tip of the Day. In a moment first noticed by the liberal press-tracking group Media Matters, O’Reilly said this:

As we mentioned, Talking Points Memo, Michelle Obama referenced slaves building the White House in referring to the evolution of America in a positive way. It was a positive comment. The history behind her remark is fascinating. George Washington selected the site in 1791, and as president laid the cornerstone in 1792. Washington was then running the country out of Philadelphia.

Slaves did participate in the construction of the White House. Records show about 400 payments made to slave masters between 1795 and 1801. In addition, free blacks, whites, and immigrants also worked on the massive building. There were no illegal immigrants at that time. If you could make it here, you could stay here.

In 1800, President John Adams took up residence in what was then called the Executive Mansion. It was only later on they named it the White House. But Adams was in there with Abigail, and they were still hammering nails, the construction was still going on.

Slaves that worked there were well-fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government, which stopped hiring slave labor in 1802. However, the feds did not forbid subcontractors from using slave labor. So, Michelle Obama is essentially correct in citing slaves as builders of the White House, but there were others working as well. Got it all? There will be a quiz.

O’Reilly’s comments were a small line at the end of the show, so one shouldn’t make too much of them. But the riff is notable for the way it resuscitates two common threads of apology for slavery: First, that human bondage didn’t play as large a role in American history as its critics might have you believe; and second, that it wasn’t as bad as they’d have you believe, either.

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading

Obama’s invocation of the slaves who built the White House was rhetorically powerful because the building is a symbol of the United States; to say slaves built it is to imply that they built the United States. Pointing out that it was not only slaves who built it (in essence, debunking an assertion that Obama did not make) undercuts the point, and in turn connects to the long tradition of arguing that however bad slavery may have been, it was only a small, regional phenomenon in the South. But as my colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates has written, slavery was the engine of the entire antebellum American economy: “In the seven cotton states, one-third of all white income was derived from slavery. By 1840, cotton produced by slave labor constituted 59 percent of the country’s exports.” Coates quotes historian David Blight, who wrote, “Slaves were the single largest, by far, financial asset of property in the entire American economy.”

More immediately controversial was O’Reilly’s statement that slaves working at the White House “were well-fed and had decent lodgings provided by the government.” The idea that slavery was, if not a good thing, not such a bad thing overall has a long, if hardly venerable, intellectual history.

This defense of slavery as essentially benign runs, for example, through Senator John C. Calhoun’s 1837 speech defending the “peculiar institution” from the criticism of northerners. In a speech in which he labeled slavery “a positive good,” the South Carolinian contended that enslaved blacks actually had it good:

Compare his condition with the tenants of the poor houses in the more civilized portions of Europe—look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poorhouse.

Some 20 years later, another senator from South Carolina, James Henry Hammond, made the same point. Speaking to Northerners, he contended:

The difference between us is, that our slaves are hired for life and well compensated; there is no starvation, no begging, no want of employment among our people, and not too much employment either. Yours are hired by the day, not cared for, and scantily compensated, which may be proved in the most painful manner, at any hour in any street in any of your large towns. Why, you meet more beggars in one day, in any single street of the city of New York, than you would meet in a lifetime in the whole South.

Of course, that wasn’t quite all of it. Hammond added that the manifest inferiority of blacks further not only justified but practically sanctified the endeavor:

We do not think that whites should be slaves either by law or necessity. Our slaves are black, of another and inferior race. The status in which we have placed them is an elevation. They are elevated from the condition in which God first created them, by being made our slaves. None of that race on the whole face of the globe can be compared with the slaves of the South. They are happy, content, uninspiring, and utterly incapable, from intellectual weakness, ever to give us any trouble by their aspirations.

It is not hard to find contemporary accounts from slaves who were neither happy nor content—and whose eloquent testimony accounts to their inspiration, capability, and intellectual powers. If many whites like Hammond were unable to see this, however, others were not so blinkered. As O’Reilly noted, Michelle Obama’s predecessor as first lady, Abigail Adams was living in the White House at the time when slaves were building it, and she recorded her observations of those working on landscaping the grounds.

“The effects of Slavery are visible every where; and I have amused myself from day to day in looking at the labour of 12 negroes from my window, who are employd with four small Horse Carts to remove some dirt in front of the house,” she wrote. Moreover, Mrs. Adams took note of their condition—and her observation stands at odds with O’Reilly’s:

Two of our hardy N England men would do as much work in a day as the whole 12, but it is true Republicanism that drive the Slaves half fed, and destitute of cloathing, ... to labour, whilst the owner waches about Idle, tho his one Slave is all the property he can boast.

Adams’s rebuke to O’Reilly is not the first time that a benign recollection of slavery has broken apart on the shoals of reality.

https://www.newenglandhistoricalsoc...-boston-runaway-who-ended-slavery-in-england/

James Somerset, the Boston Runaway Who Ended Slavery in England

In 1771, James Somerset languished in an English prison ship that would soon set sail for Jamaica. From there, he would be sold to a sugar plantation owner who would probably work him to death well before he reached old age.

But he had friends in England, and they went to court asking for a writ of habeas corpus. And so the prison ship captain dutifully took James Somerset to the Court of King’s Bench, where a judge would decide whether he had been legally imprisoned.

He hadn’t. And the judge’s decision in Stewart v. Somerset would end slavery in England, at least in the public’s mind. It sent American Southerners into the patriot camp, fearing that England would take away their slaves. And it inspired enslaved men and women to sue for their freedom in the northern colonies.

Granville Sharp

James Somerset

A Boston customs collector named Charles Stewart bought James Somerset from a Virginia plantation owner. He brought him to England in 1769, but James Somerset escaped. Stewart caught up with him, however, and had him incarcerated on the prison ship Ann and Mary.

But James Somerset had been baptized a Christian in England, and his three godparents went to court to set him free. England’s leading abolitionist, Granville Sharp, assembled a team of five lawyers to defend James Somerset. Frederick Douglass would later quote one of those lawyers, an Irishman named John Philpot Stewart.

The lawyers argued that no law authorized slavery in England.

Stewart’s lawyers argued that property rights took precedence over human rights. Plus, they pointed to the danger of freeing all 15,000 enslaved black people in England.

Lord Mansfield, who ruled in favor of James Somerset

Air Too Pure

In 1772, Lord Mansfield, the chief justice, ruled on the case. He decided that slavery had no basis in natural law or in English law. He found slavery so odious, he wrote, that it required Parliament to pass a law to legitimize it.

Lord Mansfield’s decision did not include a quotation often attributed to him: “This air is too pure for a slave to breathe in.”

Shock Waves

Slavery did persist in England, however, for another six decades after the ruling. James Somerset, though, had set in motion a series of actions that would ultimately end slavery in England. And his legal victory persuaded the English public at large that no man was a slave on English soil.

In the American colonies, of course, it would take a Civil War to end slavery.

During the run-up to the American Revolution, the colonial newspapers reported extensively on Stewart v. Somerset. The case created a sensation, especially in the South. Plantation owners realized that Parliament could not only tax them without representing them, it could free their slaves.

The Massachusetts General Court in 1771 had actually drafted a bill to emancipate the slaves, but the patriot leaders killed it. James Warren explained it “would have a bad effect on the union of the colonies.”

James Warren by John Singleton Copley

Selfish Colonials

Historian Alan Taylor argues that James Somerset’s victory persuaded many African Americans to take the Loyalist side in the looming revolution.

“Many enslaved men and women began to look to the king as a potential liberator,” Taylor wrote. African-American preachers preached the king ‘was about to alter the World and set the Negroes Free.’ The selfish colonials had blocked his wishes.

Elizabeth Freeman played an important role in ending the slave trade.

Some colonies did take the battle for liberty to include more than just white men. Vermont abolished slavery in 1777, and Pennsylvania followed in 1780, Massachusetts in 1783 and Connecticut in 1784.

In Massachusetts, two enslaved servants followed James Somerset’s example and filed freedom suits. Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker both won their cases, effectively ending slavery in Massachusetts.

James Somerset presumably died in England – a free man.

James Somerset, the Boston Runaway Who Ended Slavery in England

In 1771, James Somerset languished in an English prison ship that would soon set sail for Jamaica. From there, he would be sold to a sugar plantation owner who would probably work him to death well before he reached old age.

But he had friends in England, and they went to court asking for a writ of habeas corpus. And so the prison ship captain dutifully took James Somerset to the Court of King’s Bench, where a judge would decide whether he had been legally imprisoned.

He hadn’t. And the judge’s decision in Stewart v. Somerset would end slavery in England, at least in the public’s mind. It sent American Southerners into the patriot camp, fearing that England would take away their slaves. And it inspired enslaved men and women to sue for their freedom in the northern colonies.

Granville Sharp

James Somerset

A Boston customs collector named Charles Stewart bought James Somerset from a Virginia plantation owner. He brought him to England in 1769, but James Somerset escaped. Stewart caught up with him, however, and had him incarcerated on the prison ship Ann and Mary.

But James Somerset had been baptized a Christian in England, and his three godparents went to court to set him free. England’s leading abolitionist, Granville Sharp, assembled a team of five lawyers to defend James Somerset. Frederick Douglass would later quote one of those lawyers, an Irishman named John Philpot Stewart.

The lawyers argued that no law authorized slavery in England.

Stewart’s lawyers argued that property rights took precedence over human rights. Plus, they pointed to the danger of freeing all 15,000 enslaved black people in England.

Lord Mansfield, who ruled in favor of James Somerset

Air Too Pure

In 1772, Lord Mansfield, the chief justice, ruled on the case. He decided that slavery had no basis in natural law or in English law. He found slavery so odious, he wrote, that it required Parliament to pass a law to legitimize it.

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law [statute]… Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from the decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged

Lord Mansfield’s decision did not include a quotation often attributed to him: “This air is too pure for a slave to breathe in.”

Shock Waves

Slavery did persist in England, however, for another six decades after the ruling. James Somerset, though, had set in motion a series of actions that would ultimately end slavery in England. And his legal victory persuaded the English public at large that no man was a slave on English soil.

In the American colonies, of course, it would take a Civil War to end slavery.

During the run-up to the American Revolution, the colonial newspapers reported extensively on Stewart v. Somerset. The case created a sensation, especially in the South. Plantation owners realized that Parliament could not only tax them without representing them, it could free their slaves.

The Massachusetts General Court in 1771 had actually drafted a bill to emancipate the slaves, but the patriot leaders killed it. James Warren explained it “would have a bad effect on the union of the colonies.”

James Warren by John Singleton Copley

Selfish Colonials

Historian Alan Taylor argues that James Somerset’s victory persuaded many African Americans to take the Loyalist side in the looming revolution.

“Many enslaved men and women began to look to the king as a potential liberator,” Taylor wrote. African-American preachers preached the king ‘was about to alter the World and set the Negroes Free.’ The selfish colonials had blocked his wishes.

Elizabeth Freeman played an important role in ending the slave trade.

Some colonies did take the battle for liberty to include more than just white men. Vermont abolished slavery in 1777, and Pennsylvania followed in 1780, Massachusetts in 1783 and Connecticut in 1784.

In Massachusetts, two enslaved servants followed James Somerset’s example and filed freedom suits. Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker both won their cases, effectively ending slavery in Massachusetts.

James Somerset presumably died in England – a free man.

Last edited:

blackpast.org

James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772) •

David H. Anthony

5-6 minutes

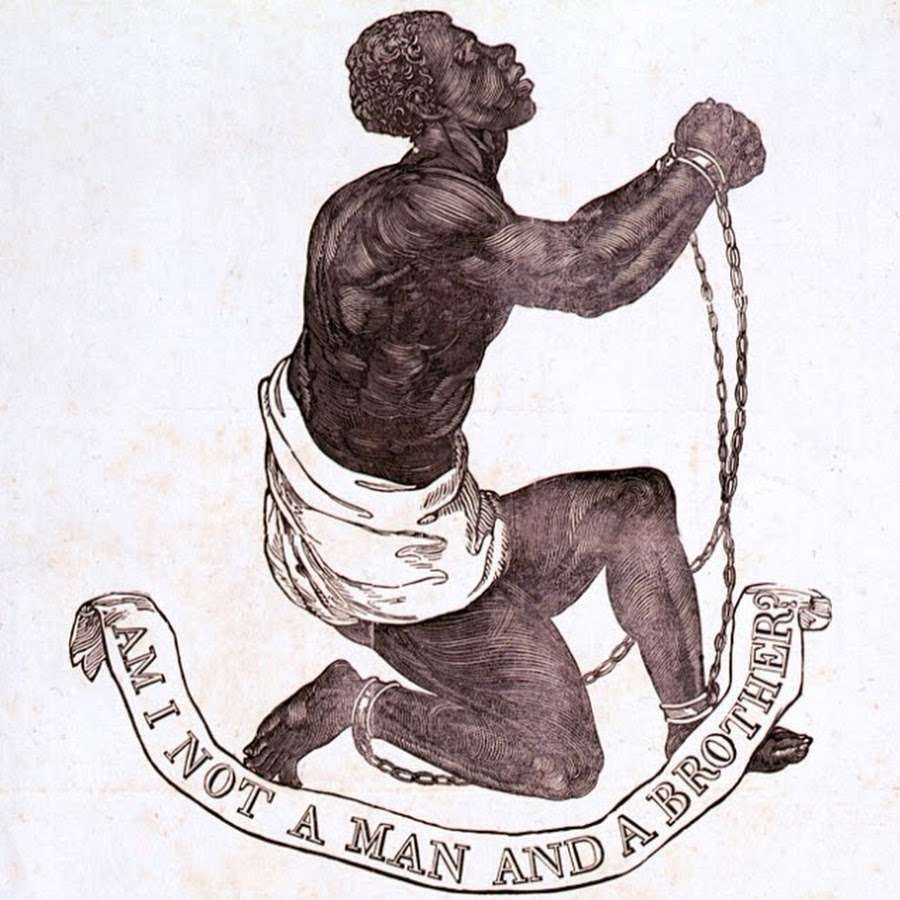

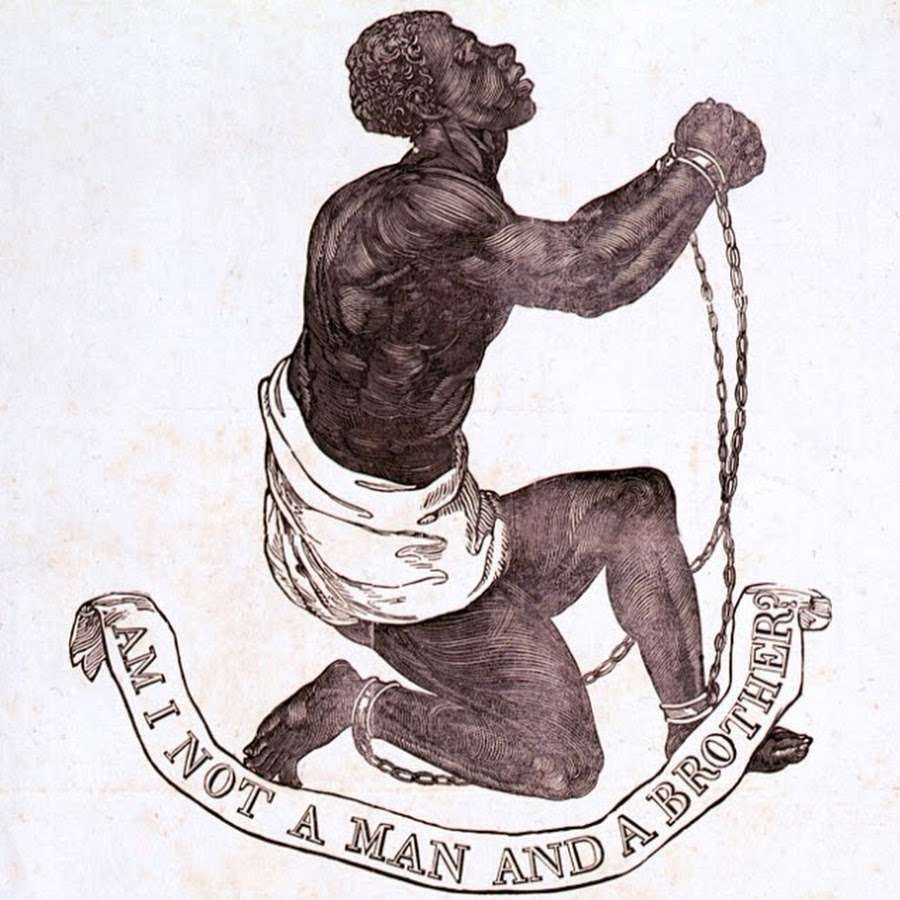

Official Medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society, 1795

Public domain image

James Sommersett was the subject of a landmark legal case in Great Britain, which was the first major step in imposing limits on Trans-Atlantic African slavery. Sommersett entered the pages of history when in 1771, he fled his North American owner, Charles Stewart, while both were living in London, England. Sommersett was originally purchased in Virginia and had been bought to Britain by Stewart from Boston, Massachusetts in 1769. He fled two years later and was apprehended on the Ann and Mary, a ship bound for Jamaica.

Sommersett’s cause was taken up by Granville Sharp, a member of Parliament and the leading abolitionist of his era. Once Sharp learned that bondsman Sommersett had been transported to England on a business trip and upon capture was spirited and shackled on board a British vessel, he applied for and was granted a writ of habeas corpus which ordered Stewart to deliver Sommersett to the King’s Bench in January 1772 to determine his legal status. Sharp organized a five-attorney legal defense team led by prominent barrister Francis Hargrave who argued the case before Hon. William Murray, Earl of Mansfield and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, England’s highest common law court.

At issue was whether a slave, even if owned in British Colonial America was by dint of residing in Britain still to be legally regarded as chattel or should be considered free. Francis Hargrave argued that by being on the soil of Great Britain, Sommersett could not remain enslaved. On June 22, 1772 Lord Mansfield decided in Somerset v. Stewart that Sommersett was to be released since no English law sanctioned slavery in Great Britain.

Sommersett’s case had differential impacts on both sides of the Atlantic. Within England it gave impetus to the nascent abolitionist movement led by Sharp and eventually William Wilberforce but which included late 18th Century black Britishers Olaudah Equiano, Quobna Ottobah Cuguano, and Ignatius Sancho. The case also moved the debate over slavery to the British Parliament. Britain’s highest legislative body ended the Empire’s participation in the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade in 1807. Twenty-six years later Parliament’s passage of the Emancipatory Act of 1833, sounded the death knell for slaveholding throughout the British Empire.

British colonists in North America, however, did not react as favorably to the precedent set by Sommersett. Twenty-two of the 24 colonial newspapers covered the trial and their responses were generally hostile with the most vehement opposition coming from newspapers in the Southern colonies where slavery was firmly entrenched. In 1772, only the Society of Friends (Quakers) was opposed to slavery. Slavery ended in 1865 only after a bloody civil war in the United States, and 93 years after Lord Mansfield’s decision.

James Sommersett disappeared from public view after his trial and is presumed to have died in Great Britain sometime after 1772.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this accessible to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone!

Cite this article in APA format:

Anthony, D. (2011, August 23). James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772). BlackPast.org. James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772) •

Source of the author's information:

Francis Hargrave, An Argument in the Case of James Sommersett, a Negro, Lately Determined by the Court of King’s Bench: wherein it is attempted to demonstrate the present unlawfulness of Domestic slavery in England. To Which is Prefixed, a State of the Case. By Mr. Hargrave, one of the counsel for the Negro (London and Boston, reprinted by E. Russell, 1774; William M, Wiecek, “”Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World,” University of Chicago Law Review 42 (1974), 86-146; Steven Wise, Though the Heavens May Fail: The Landmark Case that Led to the End of Human Slavery (Cambridge: Perseus/Da Capo Press, 2005)

James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772) •

David H. Anthony

5-6 minutes

Official Medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society, 1795

Public domain image

James Sommersett was the subject of a landmark legal case in Great Britain, which was the first major step in imposing limits on Trans-Atlantic African slavery. Sommersett entered the pages of history when in 1771, he fled his North American owner, Charles Stewart, while both were living in London, England. Sommersett was originally purchased in Virginia and had been bought to Britain by Stewart from Boston, Massachusetts in 1769. He fled two years later and was apprehended on the Ann and Mary, a ship bound for Jamaica.

Sommersett’s cause was taken up by Granville Sharp, a member of Parliament and the leading abolitionist of his era. Once Sharp learned that bondsman Sommersett had been transported to England on a business trip and upon capture was spirited and shackled on board a British vessel, he applied for and was granted a writ of habeas corpus which ordered Stewart to deliver Sommersett to the King’s Bench in January 1772 to determine his legal status. Sharp organized a five-attorney legal defense team led by prominent barrister Francis Hargrave who argued the case before Hon. William Murray, Earl of Mansfield and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, England’s highest common law court.

At issue was whether a slave, even if owned in British Colonial America was by dint of residing in Britain still to be legally regarded as chattel or should be considered free. Francis Hargrave argued that by being on the soil of Great Britain, Sommersett could not remain enslaved. On June 22, 1772 Lord Mansfield decided in Somerset v. Stewart that Sommersett was to be released since no English law sanctioned slavery in Great Britain.

Sommersett’s case had differential impacts on both sides of the Atlantic. Within England it gave impetus to the nascent abolitionist movement led by Sharp and eventually William Wilberforce but which included late 18th Century black Britishers Olaudah Equiano, Quobna Ottobah Cuguano, and Ignatius Sancho. The case also moved the debate over slavery to the British Parliament. Britain’s highest legislative body ended the Empire’s participation in the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade in 1807. Twenty-six years later Parliament’s passage of the Emancipatory Act of 1833, sounded the death knell for slaveholding throughout the British Empire.

British colonists in North America, however, did not react as favorably to the precedent set by Sommersett. Twenty-two of the 24 colonial newspapers covered the trial and their responses were generally hostile with the most vehement opposition coming from newspapers in the Southern colonies where slavery was firmly entrenched. In 1772, only the Society of Friends (Quakers) was opposed to slavery. Slavery ended in 1865 only after a bloody civil war in the United States, and 93 years after Lord Mansfield’s decision.

James Sommersett disappeared from public view after his trial and is presumed to have died in Great Britain sometime after 1772.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this accessible to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone!

Cite this article in APA format:

Anthony, D. (2011, August 23). James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772). BlackPast.org. James Sommersett (ca. 1741-ca. 1772) •

Source of the author's information:

Francis Hargrave, An Argument in the Case of James Sommersett, a Negro, Lately Determined by the Court of King’s Bench: wherein it is attempted to demonstrate the present unlawfulness of Domestic slavery in England. To Which is Prefixed, a State of the Case. By Mr. Hargrave, one of the counsel for the Negro (London and Boston, reprinted by E. Russell, 1774; William M, Wiecek, “”Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World,” University of Chicago Law Review 42 (1974), 86-146; Steven Wise, Though the Heavens May Fail: The Landmark Case that Led to the End of Human Slavery (Cambridge: Perseus/Da Capo Press, 2005)