Nah they didn’t ask for qualifications. Just had to have your Vax card to show you had the two previous shots.Did they ask for qualifications or you just walked in and got it???

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

COVID-19 Pandemic (Coronavirus)

- Thread starter null

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?$cam-U-Well_Jack$on

Superstar

Nah they didn’t ask for qualifications. Just had to have your Vax card to show you had the two previous shots.

Shiddddddd. I'm finna handle that in da next few days, then.

Prince.Skeletor

Don’t Be Like He-Man

Other viruses are known to infect the heart and spur inflammation. Coxsackieviruses, for example, are a major cause of myocarditis and other heart-muscle defects. When viral pathogens such as these strike, people usually develop chest pains, shortness of breath or some other overt signs of illness. SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, is different.

Not only do few people diagnosed with coronavirus-induced myocarditis complain of cardiac issues, but they can also have few or no symptoms of infection whatsoever.

Raul Mitrani is a cardiac electrophysiologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida. Last year, Mitrani and his colleagues gave a name to the constellation of heart-related problems observed among people recovering from COVID-19: post-COVID-19 cardiac syndrome1. “There are a lot of unknowns still,” Mitrani says. “But what we’re ultimately worried about is heart decompensation and dangerous arrhythmias.” The former involves a sudden worsening of heart failure; the latter is an uneven heartbeat. Both can trigger sudden cardiac death.

Scientists have begun to study the phenomenon in the lab, exposing heart tissue derived from stem cells to SARS-CoV-2 and chronicling the damage inflicted. And clinicians are continuing to track people who have had COVID-19 to better understand the long-term cardiac risks.

Although it’s too soon to make definitive conclusions, the extent of cardiac injury and inflammation observed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—the most definitive and comprehensive tool for diagnosing myocarditis—has put the field on high alert.

“We need to understand more about what these MRI abnormalities mean,” says Saurabh Rajpal, a cardiologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

From the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that the coronavirus was wreaking havoc on the heart. Initial reports described people with worryingly high levels of the protein troponin in their blood, an indicator of cardiac injury.

Acute heart failure, arrhythmias and blood clots are all problems for people hospitalized with COVID-19. Autopsies frequently show signs of the virus’s genetic material inside cardiac tissue, a consequence of the fact that the receptor through which SARS-CoV-2 invades lung cells is also found in abundance in heart tissue.

Researchers soon found out that the heart-wrecking effects of COVID-19 are not limited to people with symptoms, or even to people with active infections. Last July, researchers described2 abnormal imaging findings on heart scans taken from people who had recently had COVID-19, some of whom were asymptomatic. Of the 100 people studied, 78 had some kind of heart irregularity around two months after infection—and 60 showed signs of ongoing myocardial inflammation.

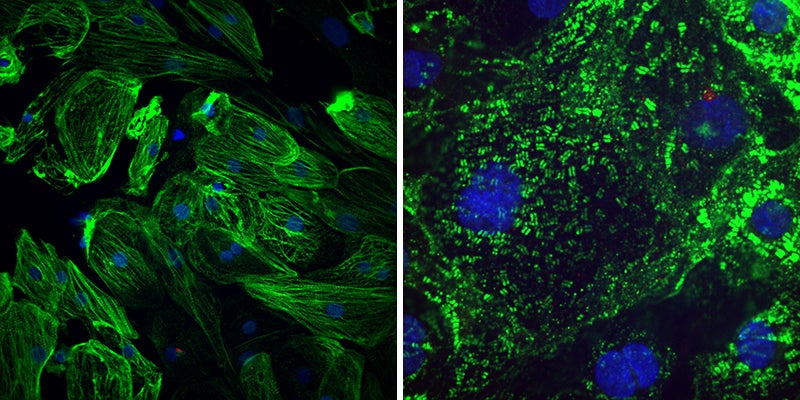

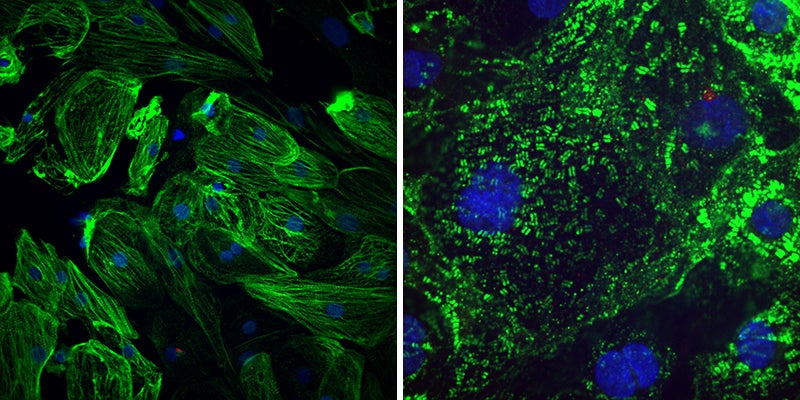

Healthy heart muscle (left) have long fibres that allow them to contract. The virus SARS-CoV-2 causes these fibres to break apart (right), which might explain the lasting cardiac effects seen in people who have had COVID-19. Credit: Gladstone Institutes

“That was quite worrisome and created quite a stir,” Mitrani says. In particular, the idea that COVID-19 could stealthily inflict sustained damage on the heart raised alarm bells among the sports-medicine community, given the particularly grave risk that myocarditis poses for athletes. Citing “potential serious cardiac side effects”, last August, several US university leagues temporarily put their seasons on hold.

COVID’s cardiac connection

This is worrying

Not only do few people diagnosed with coronavirus-induced myocarditis complain of cardiac issues, but they can also have few or no symptoms of infection whatsoever.

Raul Mitrani is a cardiac electrophysiologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida. Last year, Mitrani and his colleagues gave a name to the constellation of heart-related problems observed among people recovering from COVID-19: post-COVID-19 cardiac syndrome1. “There are a lot of unknowns still,” Mitrani says. “But what we’re ultimately worried about is heart decompensation and dangerous arrhythmias.” The former involves a sudden worsening of heart failure; the latter is an uneven heartbeat. Both can trigger sudden cardiac death.

Scientists have begun to study the phenomenon in the lab, exposing heart tissue derived from stem cells to SARS-CoV-2 and chronicling the damage inflicted. And clinicians are continuing to track people who have had COVID-19 to better understand the long-term cardiac risks.

Although it’s too soon to make definitive conclusions, the extent of cardiac injury and inflammation observed using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—the most definitive and comprehensive tool for diagnosing myocarditis—has put the field on high alert.

“We need to understand more about what these MRI abnormalities mean,” says Saurabh Rajpal, a cardiologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

From the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that the coronavirus was wreaking havoc on the heart. Initial reports described people with worryingly high levels of the protein troponin in their blood, an indicator of cardiac injury.

Acute heart failure, arrhythmias and blood clots are all problems for people hospitalized with COVID-19. Autopsies frequently show signs of the virus’s genetic material inside cardiac tissue, a consequence of the fact that the receptor through which SARS-CoV-2 invades lung cells is also found in abundance in heart tissue.

Researchers soon found out that the heart-wrecking effects of COVID-19 are not limited to people with symptoms, or even to people with active infections. Last July, researchers described2 abnormal imaging findings on heart scans taken from people who had recently had COVID-19, some of whom were asymptomatic. Of the 100 people studied, 78 had some kind of heart irregularity around two months after infection—and 60 showed signs of ongoing myocardial inflammation.

Healthy heart muscle (left) have long fibres that allow them to contract. The virus SARS-CoV-2 causes these fibres to break apart (right), which might explain the lasting cardiac effects seen in people who have had COVID-19. Credit: Gladstone Institutes

“That was quite worrisome and created quite a stir,” Mitrani says. In particular, the idea that COVID-19 could stealthily inflict sustained damage on the heart raised alarm bells among the sports-medicine community, given the particularly grave risk that myocarditis poses for athletes. Citing “potential serious cardiac side effects”, last August, several US university leagues temporarily put their seasons on hold.

COVID’s cardiac connection

This is worrying

Last edited:

Joe Budden

Banned

But but it’s just the flu

Another win for booster boys

Do my own YouTube research gang going out sad

Do my own YouTube research gang going out sad

Ethnic Vagina Finder

The Great Paper Chaser

2020 doing more in the first month than happened in the while last decade. Selling more than the 2010's in its first week. Respek on its name.

Killer Chinese coronavirus 'may be passed through SALIVA' as outbreak reaches Taiwan, death toll rises to six and 300 patients are struck down - and experts predict mystery disease will continue to spread

The deadly Chinese coronavirus that has sickened more than 300 people could be passed through saliva, officials today suggested.

- Chinese officials yesterday confirmed the virus has spread between humans

- Fifteen healthcare workers have caught the respiratory virus, figures show

- A total of 313 people in Asia have now tested positive for the unnamed virus

- Three other countries have reported cases - Thailand, Japan and South Korea

- Three more deaths have been announced today, taking the death toll to six

China’s National Health Commission yesterday confirmed that the never-before-seen coronavirus had spread between humans.

And now the official body has revealed the unnamed infection is spread from the lungs and may travel in saliva – such as through coughs.

Taiwan today confirmed its first case of the lethal bug, which has killed six people in the Chinese city of Wuhan, home to 11million people.

Coronavirus outbreak in China has now killed six people | Daily Mail Online

We are overdue another Flu Pandemic

It's here

Where it all started

post 1

It’s crazy how an entire pandemic is cataloged from beginning to now on a message board

Your source is a blog website, stop being a bytch

I don't think we lost yetAnother win for booster boys

Do my own YouTube research gang going out sad

I'm vaxxxed and still waiting on wings so I can get to trees better:

I'm vaxxxed and still waiting on wings so I can get to trees better:

Prince.Skeletor

Don’t Be Like He-Man

Your source is a blog website, stop being a bytch

Scientific American is a blog website?

Well yeah

Dafunkdoc_Unlimited

Theological Noncognitivist Since Birth

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2012

- Messages

- 45,062

- Reputation

- 8,000

- Daps

- 122,429

- Reppin

- The Wrong Side of the Tracks

For Scientific purposes can they put the vax in those cultures and see what happens to the heart tissue

Already done that about 4 BILLION times.

For Scientific purposes can they put the vax in those cultures and see what happens to the heart tissue

Covid-19 infections leave an impact on the heart, raising concerns about lasting damage