You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Confederate flag waving Asian

- Thread starter Responsible Allen Iverson

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Shiva

Avatāra. Annihilator. Gone To The 5th Dimension.

I'm Asian and this dude ain't shyt. If I caught this dude lacking in public he'd get duct taped and taken to the basement on sight. 12 hours later he'd be in the ocean.

Always said members of the community need to stop kissing white ass, the people in power see us as scum as well, in a different light. They keep us down with stereotypes and use those to brainwash the weak willed into believing they're the model minority, while most white people see us as a threat and want us dead. People like this guy give other Asian Americans a bad name.

Always said members of the community need to stop kissing white ass, the people in power see us as scum as well, in a different light. They keep us down with stereotypes and use those to brainwash the weak willed into believing they're the model minority, while most white people see us as a threat and want us dead. People like this guy give other Asian Americans a bad name.

Insun Park

Fukk Em

Indians are the worst. Never met a good one ever. Biggest white ass kissers ever. Wouldn't piss on one if they were on fireyall better realize these minorities with us will automatically go with whites if push comes to shove. Had some indian dude on my facebook feed reposting tomi lahren videos talking bout he agrees with everything she says. Blocked dude in an instant. Some of these dudes honestly think that they are white just because they are not black.

Marco Zen

Black Privilege

He's got issues, another Elliot Rodger

I lasted about 9 seconds.

This fukkin guy

this dude would have been building railroadsWere there even any Asians living in the Confederacy?

iliketurtles

Do Right And Kill Everything

Rat eaters getting bold

I have seen some fukked up things living in the south, never have I seen a redneck asian.

NBA Youngbreh

DaDumbWay

"Hurry up n buy nagger!"

He wants acceptance so bad.

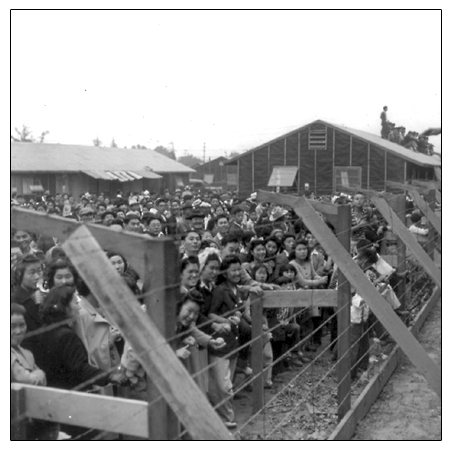

The Los Angeles Race Riots of 1871, where White people raged through Chinatown and lynched 17 people

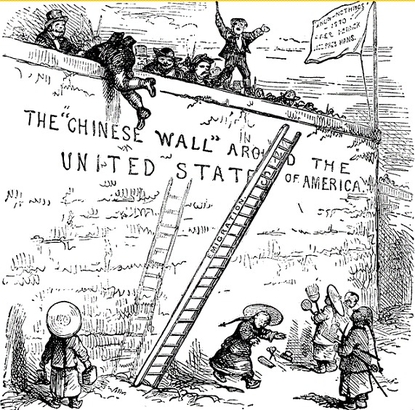

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first general anti-immigrant law in American history, where the USA basically banned all Chinese immigrants from entering for the next 60+ years

The Rock Springs Massacre of 1885, where a mob killed 28 Chinese miners and destroyed their community

The Seattle Riot of 1886, where 350 Chinese people were forcibly removed from their homes in an attempt to cleanse Seattle of Chinese

The Snake River Massacre of 1887, where frontiersmen killed 34 Chinese miners

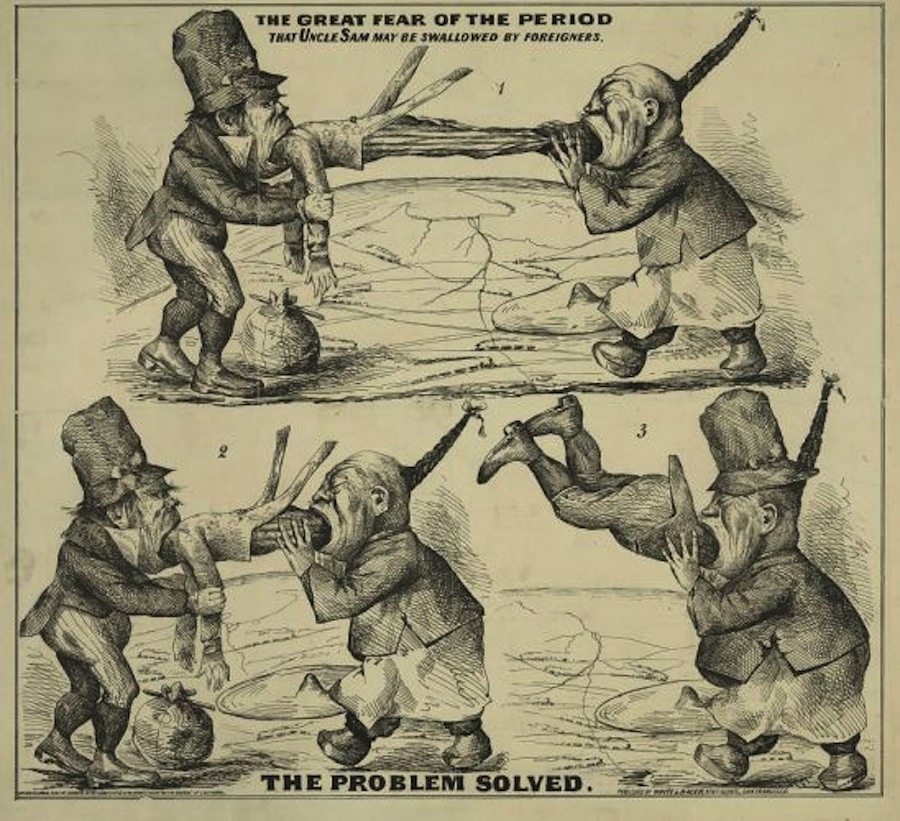

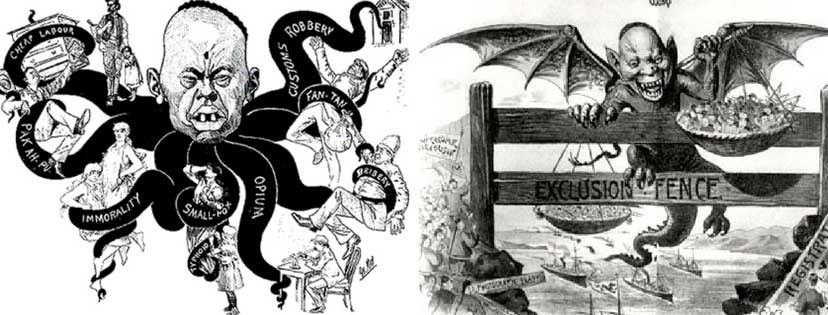

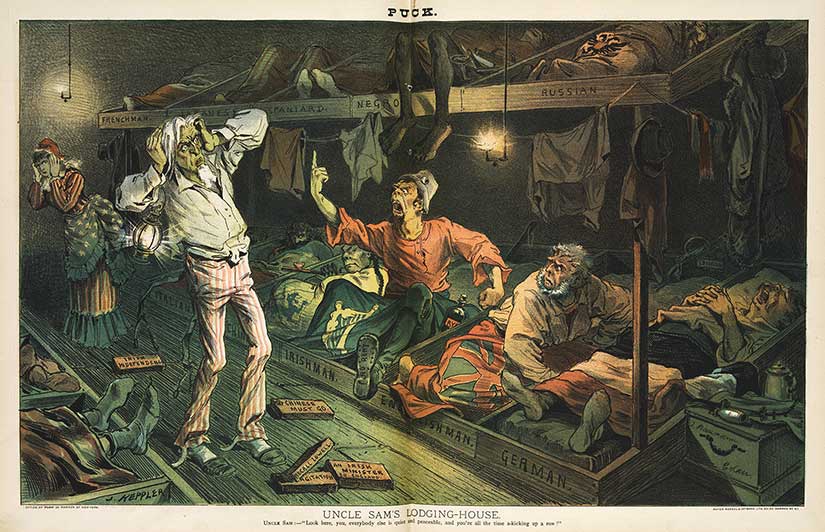

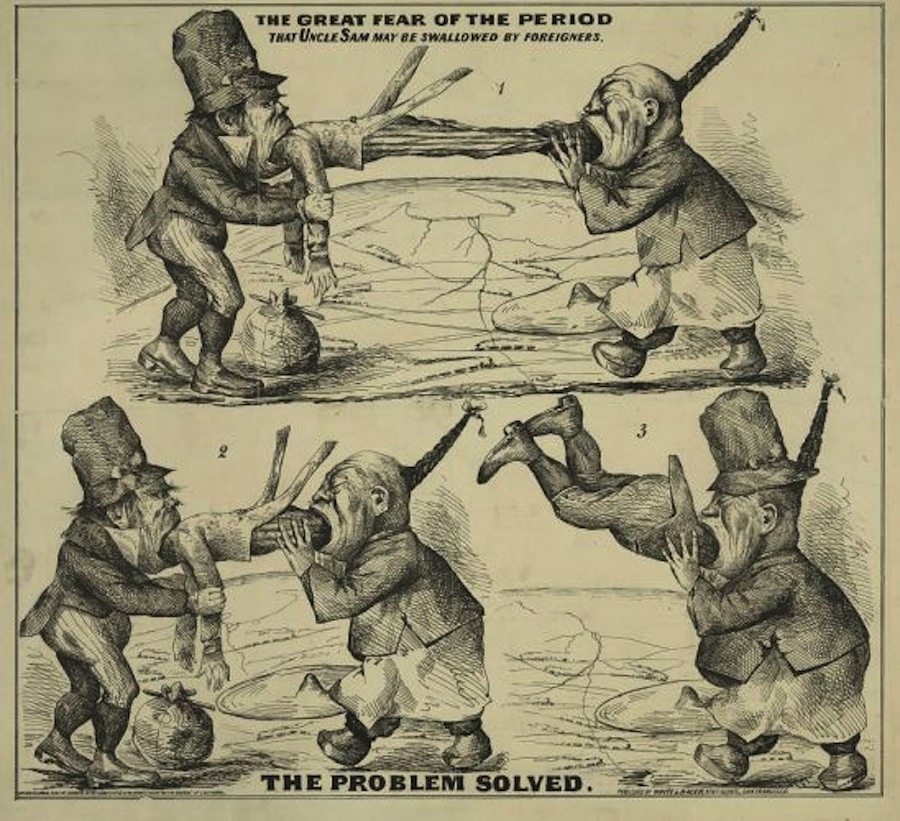

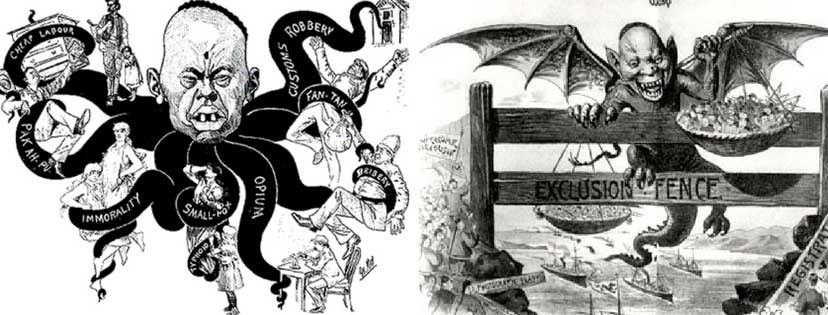

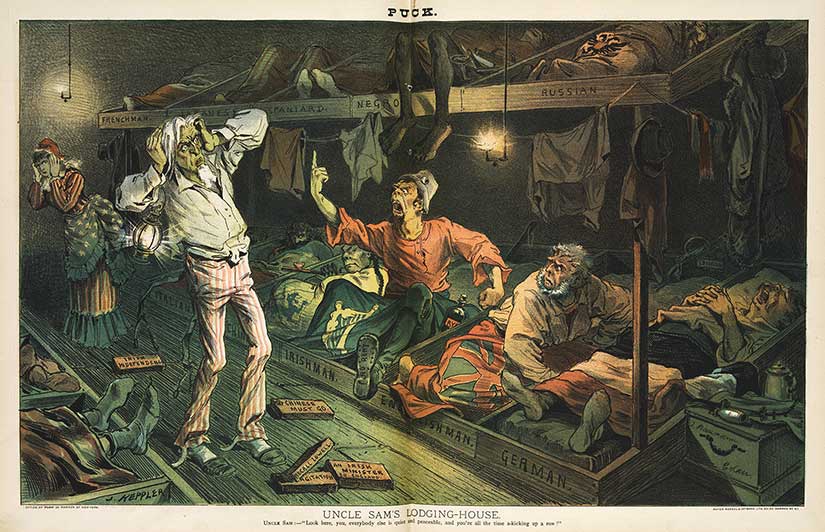

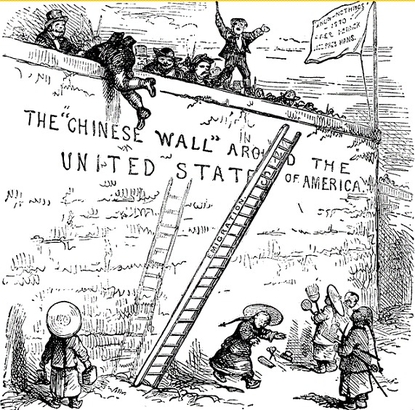

And some racist cartoons of the time:

Here they just threw everything together:

If he has the slightest historical knowledge though he can find a ton of anti-Chinese crap that went down too.you talked about the japanese camps, that won't apply to him and actually would work in his favor

remember not all skin folk are my kin folk, a lot of asian nations detest each other

The Los Angeles Race Riots of 1871, where White people raged through Chinatown and lynched 17 people

(p.s. - you notice how they co-opted another group in order to pull that shyt? How'd that work out for them?)The Chinese massacre of 1871 was a race riot that occurred on October 24, 1871, in Los Angeles, California, when a mob of around 500 white and mestizopersons entered Chinatown and attacked, robbed, and murdered Chinese residents.[1][2] The massacre took place on Calle de los Negros (Street of the Negroes), also referred to as "****** Alley". The mob gathered after hearing that a policeman had been shot and a rancher killed by Chinese.

An estimated 17 to 20 Chinese immigrants were hanged by the mob in the course of the riot, but most had already been shot to death. At least one was mutilated, when someone cut off a finger to get his diamond ring. Ten men of the mob were prosecuted and eight were convicted of manslaughter in these deaths. The convictions were overturned on appeal due to technicalities.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first general anti-immigrant law in American history, where the USA basically banned all Chinese immigrants from entering for the next 60+ years

Kearey, an Irish immigrant, began a fiery campaign against the Chinese. His radical speeches, each of which ended with a simple yet very clear statement, “The Chinese Must Go!”, not only attracted crowds, but spurred them to take action. In his 1878 speech, he said: “To add to our misery and despair, a bloated aristocracy has sent to China – the greatest and oldest despotism in the world – for a cheap working slave. It rakes the slums of Asia to find the meanest slave on earth – the Chinese coolie – and imports him here to meet the free American in the labor market, and still further widen the breach between the rich and poor, sill further to degrade white labor. These cheap slaves fill every place. Their dress is scant and cheap. Their food is rice from China. They lodge twenty in a room, ten by ten. They are whipped curs, abject in docility, mean, contemptible and obedient in all things. They have no wives, children or dependents.” (Seonnichsen).

Another spokesperson for those in favour of the discrimination of the Chinese was Senator James G. Blaine. “Ought we to exclude them?” was his question on the 14th of February 1879, to which he replied: “The question lies in my mind thus: either the Anglo-Saxon race will possess the Pacific slope or the Mongolians will possess it.” (Andrew Gyory, Closing the Gate: Race, Politics, and the Chinese Exclusion Act). From these few words, Blaine appeared to be not only arrogant but also ignorant; his speeches were filled with strong racial prejudice. “In a widely reprinted letter to the New York Tribune…, he elaborated his position, calling Chinese immigration “vicious,” “odious,” “abominable,” “dangerous,” and “revolting… If as a nation we have the right to keep out infectious diseases,if we have the right to exclude the criminal classes from coming to us, we surely have the right to exclude that immigration which reeks with impurity and which cannot come to us without plenteously sowing the seeds of moral and physical disease, destitution, and death,” Leaving no doubt as to where he stood, the Maine Republican concluded, “I am opposed to the Chinese coming here; I am opposed to making them citizens; I am opposed to making them voters.”

The Rock Springs Massacre of 1885, where a mob killed 28 Chinese miners and destroyed their community

In the buildings at the Number 3 mine, white men shot Chinese workers, killing several. The mob moved into Chinatown from three directions, pulling some Chinese men from their homes and shooting others as they came into the street. Most fled, dashing through the creek, along the tracks or up the steep bluffs and out into the hills beyond. A few ran straight for the mob and met their deaths. White women took part in the killing, too.

The mob turned back through Chinatown, looting the shacks and houses, and then setting them on fire. More Chinese were driven out of hiding by the flames and were killed in the streets. Others burned to death in their cellars. Still others died that night out on the hills and prairies from thirst, the cold and their wounds.

The Seattle Riot of 1886, where 350 Chinese people were forcibly removed from their homes in an attempt to cleanse Seattle of Chinese

On the morning of February 7, many "committees" forced their way into Chinese homes, demanding the Chinese pack their bags and report to the steamship Queen of the Pacific at 1pm. The committees set up wagons through Seattle's Chinatown to haul baggage down to the pier. After a search was conducted for Chinese who fled or hid, the committees led some 350 Chinese from Chinatown to the pier. Local Sheriff John McGraw was aroused to enforce law and order with his force of deputies, but McGraw was sympathetic to the plight of the Knights and simply protected the Chinese immigrants from violence on their way to the pier. When Governor Squire ordered the dispersal of the mob and the release of the Chinese, the riotous mob ignored him. Thus, Squire called for the local "Seattle Rifles" militia and requested the aid of federal troops to assist McGraw.

The Snake River Massacre of 1887, where frontiersmen killed 34 Chinese miners

The killers were believed to be a gang of Oregon horse thieves, ranch hands and a 15-year-old schoolboy. Their crime was discovered when the mutilated bodies of the Chinese miners -- the killers apparently had hacked their victims with axes after they were dead -- began showing up 65 miles downstream at Lewiston, Idaho.

"It was the most cold-blooded, cowardly treachery I have ever heard tell of on this coast," Judge Joseph K. Vincent, a 19th-century Idaho justice of the peace and U.S. commissioner, is quoted as saying in Nokes' book. "Every one was shot and cut up and stripped and thrown in the river."

The killers' take probably amounted to 312 ounces of gold dust valued at roughly $5,000 at the 1887 rate of exchange of $16 per ounce, Nokes says. One of the robbers, 21-year-old J.T. Canfield, was delegated to sell the gold for money and probably ended up with all of it, he says.

And some racist cartoons of the time:

Here they just threw everything together: