‘Code red’: Melbourne businesses say Omicron wave more damaging than lockdown

Hash Tayeh, owner of Victorian food chain Burgertory, says 260 of his 400 staff have had Covid. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Staff shortages and drop in consumer confidence leave Australian businesses asking for urgent government support

by Ben Butler

Hash Tayeh has been back behind the counter at the burger chain he founded, Burgertory, for the first time in three years as he struggles to keep the business going in the face of the Omicron wave.

He has been doing night shifts at his outlet on Chapel Street in Melbourne, a fashionable shopping and entertainment strip which local traders say has been overwhelmed by Covid-related staff shortages.

The pandemic taught him to “just never get too comfortable and always be humble,” he said.

“So I was helping them take orders, take out the rubbish, mop the floors, do the dishes – wherever they needed me.”

Two hundred and sixty of Burgertory’s 400 staff have had Covid.

In addition to working in the Chapel Street restaurant, he cut five hours a day from its opening hours. He also closed four other Burgertory outlets due to lack of staff, although he was able to reopen one of them on Wednesday.

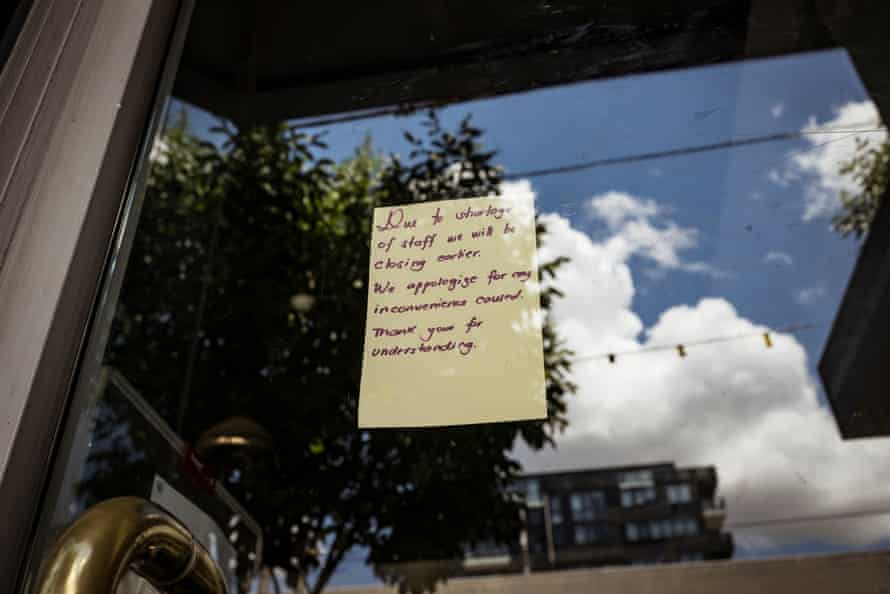

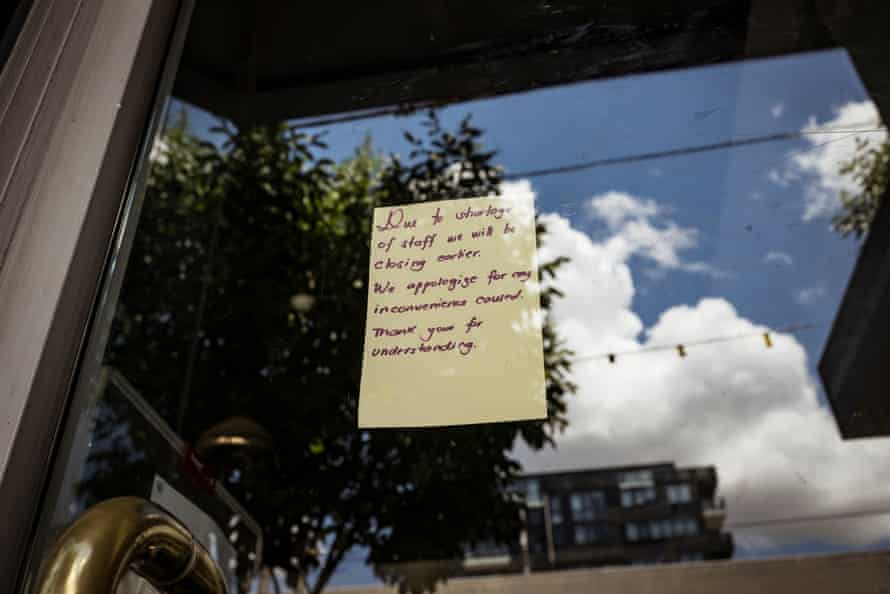

Thirty five per cent of Chapel Street workers either have or have had Covid, according to a local business group. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Staff shortages have ravaged Australian business, smashing apart the supply chains that supermarkets rely on to keep food on the shelves, cutting the supply of chicken, grounding planes, and crushing tourism and hospitality businesses on the east coast.

Consumer confidence has plunged as casual workers are stripped of shifts while sick or isolating, and an unofficial lockdown is in place with restaurants and bars reporting fewer customers than usual as people try to dodge the virus.

On Chapel Street, 35% of people employed by 2,200 businesses either have or have had Covid, local business group Chapel Street Precinct estimated.

“We’re keeping our head above water but we’re not making a profit at the moment,” Tayeh said.

“There’s no state support, there’s no federal support – it’s really hard at the moment.”

Chrissie Maus, the general manager of Chapel Street Precinct, is herself in isolation, recovering from Covid.

Maus’ group was in contact with the Victorian minister for small business to ask for a return to the $750-a-week disaster payment. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Maus said opening up was a ‘double edged sword’ as businesses were not receiving any financial support. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Hash Tayeh, owner of Victorian food chain Burgertory, says 260 of his 400 staff have had Covid. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Staff shortages and drop in consumer confidence leave Australian businesses asking for urgent government support

by Ben Butler

Hash Tayeh has been back behind the counter at the burger chain he founded, Burgertory, for the first time in three years as he struggles to keep the business going in the face of the Omicron wave.

He has been doing night shifts at his outlet on Chapel Street in Melbourne, a fashionable shopping and entertainment strip which local traders say has been overwhelmed by Covid-related staff shortages.

The pandemic taught him to “just never get too comfortable and always be humble,” he said.

“So I was helping them take orders, take out the rubbish, mop the floors, do the dishes – wherever they needed me.”

Two hundred and sixty of Burgertory’s 400 staff have had Covid.

In addition to working in the Chapel Street restaurant, he cut five hours a day from its opening hours. He also closed four other Burgertory outlets due to lack of staff, although he was able to reopen one of them on Wednesday.

Thirty five per cent of Chapel Street workers either have or have had Covid, according to a local business group. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Staff shortages have ravaged Australian business, smashing apart the supply chains that supermarkets rely on to keep food on the shelves, cutting the supply of chicken, grounding planes, and crushing tourism and hospitality businesses on the east coast.

Consumer confidence has plunged as casual workers are stripped of shifts while sick or isolating, and an unofficial lockdown is in place with restaurants and bars reporting fewer customers than usual as people try to dodge the virus.

On Chapel Street, 35% of people employed by 2,200 businesses either have or have had Covid, local business group Chapel Street Precinct estimated.

“We’re keeping our head above water but we’re not making a profit at the moment,” Tayeh said.

“There’s no state support, there’s no federal support – it’s really hard at the moment.”

Chrissie Maus, the general manager of Chapel Street Precinct, is herself in isolation, recovering from Covid.

Maus’ group was in contact with the Victorian minister for small business to ask for a return to the $750-a-week disaster payment. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian

Maus said opening up was a ‘double edged sword’ as businesses were not receiving any financial support. Photograph: Christopher Hopkins/The Guardian