GoAggieGo.

getting blitzed.

These threads are always my favorite. They don’t pop without appearances or drops from @IllmaticDelta @Supper @xoxodede @HarlemHottie @K.O.N.Y

The Negro Renaissance (1920-1930) also known as the Harlem Renaissance was a notable historical phase and a cultural and political development of great significance in the making and maturation of a Black Personality in the United States. Worthy of a genuine renaissance as the name implied, the movement in spite of some weaknesses, laid the foundations for what is known as black culture, or precisely Negro culture, in the United States. Synchronically and diachronically it marked one of the highest points, and perhaps an unsurpassed apex of Negro American nationalism since the Emancipation of the African slaves. Profoundly negro was the Harlem Renaissance and powerful was the movement to the extent that it developed beyond the American boundary to reach Europe and Africa. African Renaissance which commenced in the 1930's and the most articulate and best expressions of which were Negritude and Pan-Africanism owed its emergence in part to the Harlem Renaissance.^ The investigation in this study has been focused around three major areas of interest: (1) Afro-American influence upon African literature, (2) Afro-American impact on the awakening of African consciousness, and (3) Afro-American contribution to the rehabilitation of African history and civilization. Afro-American influence on African literature came from the Negro ethnic literature which was produced by the Negro Renaissance, its major contributors being Countee Cullen, James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, and Claude McKay. Afro-American political influence from the Renaissance period came from W. E. B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey through their writings and militancy.^ The study was conducted using historical research methodology and causal-comparative research methodology. The first methodology enabled us to bring together and closely examine the diverse historical elements which pertained to the awakening of African consciousness and the rehabilitation of African history and civilization. The causal-comparative methodology was mainly used to establish causal relationships between the literature of the Negro Renaissance and African literature.^ The study shows that Negritude and Pan-Africanism, and through them, African Renaissance, owed much to the Negro Renaissance, thus attesting to the evident contribution of Afro-Americans in the making of modern African consciousness. ^

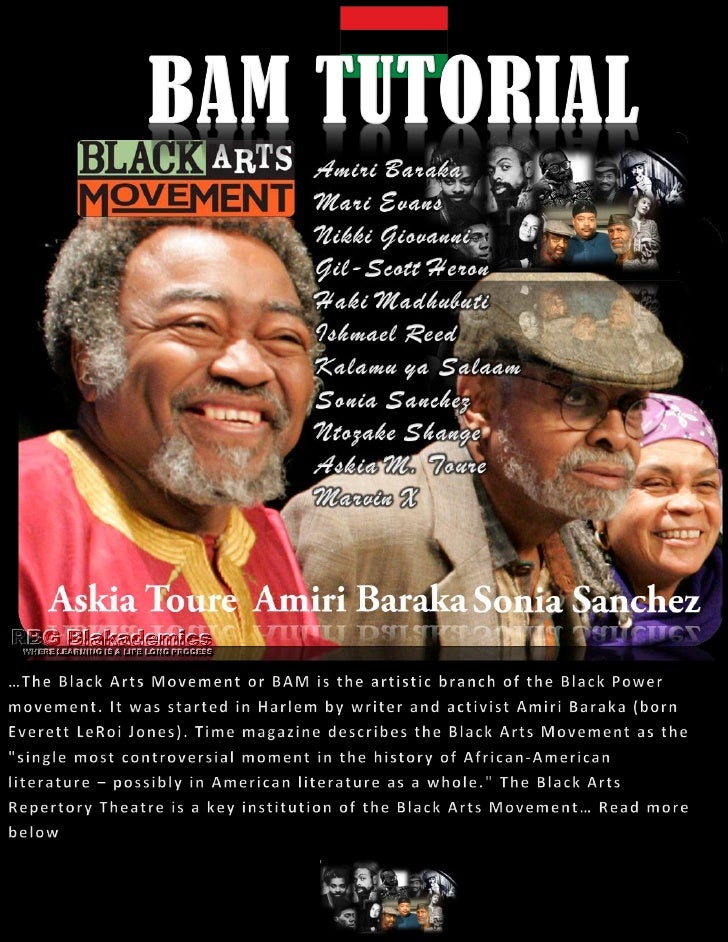

The Black Arts Movement (or BAM) was an African American-led art movement, active during the 1960s and 1970s.[3] Through activism and art, BAM created new cultural institutions and conveyed a message of black pride.[4]

Famously referred to by Larry Neal as the “aesthetic and spiritual sister of Black Power,"[5] BAM applied these same political ideas to art and literature.[6] The movement resisted traditional Western influences and found new ways to present the black experience.

The poet and playwright Amiri Baraka is widely recognized as the founder of BAM.[7] In 1965, he established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre School (BART/S) in Harlem.[8] Baraka's example inspired many others to create organizations across the United States.[4] While these organizations were short-lived, their work has had a lasting influence.

dude was a sergeant(looking at his insignia) so he was ready for that staticYou know little man on the right was a pistol to deal with.

on the right lol

on the right lol at all those respectability politic c00ns. These pictures continue to prove that it doesn't matter how we dress, speak, or act they'll never see us as human.

at all those respectability politic c00ns. These pictures continue to prove that it doesn't matter how we dress, speak, or act they'll never see us as human.

Motown Records is an American record label owned by the Universal Music Group. It was founded by Berry Gordy Jr. as Tamla Records on January 12, 1959,[2][3] and incorporated as Motown Record Corporation on April 14, 1960.[4] Its name, a portmanteau of motor and town, has become a nickname for Detroit, where the label was originally headquartered.

Motown played an important role in the racial integration of popular music as an African American-owned label that achieved crossover success. In the 1960s, Motown and its subsidiary labels (including Tamla Motown, the brand used outside the US) were the most successful proponents of the Motown sound, a style of soul music with a mainstream pop appeal. Motown was the most successful soul music label, with a net worth of $61 million. During the 1960s, Motown achieved 79 records in the top-ten of the Billboard Hot 100 between 1960 and 1969.

Motown, or the Motown sound, is a style of rhythm and blues music[2] named after the record company Motown in Detroit, where teams of songwriters and musicians produced material for girl groups, boy bands, and solo singers during the 1960s and early 1970s. The music of Motown helped a small record company become the largest Black American-owned enterprise in the country and a national music industry competitor in the United States.[3]

The sound, a sophisticated strain of R&B and pop, is known for its polished songwriting with "candid" vocal delivery.[2] Musicians involved in the production of a Motown track constituted a mix of eclectic musical backgrounds, such as jazz[7] and rhythm and blues.[3] It had a crossover[4] appeal it was called "clean R&B that sounded as white as it did black."[7] Productions featured a strong rhythm, layered instrumental sound, and memorable hooks,[8] utilizing large bands, strings, and organs.[3] Motown producers adhered to the "KISS principle" (keep it simple, stupid).[9]

Principal architects of the style were the songwriting trio Holland–Dozier–Holland and record producer Berry Gordy.[4] Their series of hits produced for solo singers as well as groups dominated the American and British charts in the late 1960s and exerted an influence on music in the United Kingdom.[5] Some of the components of the music, such as the "gospel break"[10] and four-on-the-top beat (inverted), survived in disco later in the 1970s.[11]

Smokey Robinson describes the style in the following way:

People would listen to it, and they'd say, 'Aha, they use more bass. Or they use more drums.' Bullshyt. When we were first successful with it, people were coming from Germany, France, Italy, Mobile, Alabama. From New York, Chicago, California. From everywhere. Just to record in Detroit. They figured it was in the air, that if they came to Detroit and recorded on the freeway, they'd get the Motown sound. Listen, the Motown sound to me is not an audible sound. It's spiritual, and it comes from the people that make it happen. What other people didn't realize is that we just had one studio there, but we recorded in Chicago, Nashville, New York, L.A.—almost every big city. And we still got the sound.[12]