"...don't care who they hit long as the drama's lit" - NasIran sure knows how to fire missles that hit no target.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Breaking:Iran Launches Missile Attack Near U.S Embassy In Iraq

- Thread starter Jefferson Jackson

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?He'd be the first one trying to force his way into a bomb shelter.

This is callus, but I don’t want this shyt fukking up my money

chill breh, they gone put you on a list. just kiba and be bool fam, it ain't ya story the most high movin and shakin shyt up rn. stay prayed up hope you a part of the 1/3rd, see ya in the kingdom beloved.Yup WW3 is about to be reeeeeeeeeeeal crazy

Iran, North Korea, Japan, China, Russia

against

UScacs, UKcacs, Frenchcacs, etc

And guest what, you UKRAINE LOVING nikkas are about to be tricked because African countries are about to providing oil and banking for the Opps side….

Im so fukking ready for this. fukk everyone’s world up..

that's riiiiiiiiiiiiight!

that's riiiiiiiiiiiiight!

General Mills

More often than not I tend to take that L.

I’m saying tho. They said they shot 12. Not one hit?Iran sure knows how to fire missles that hit no target.

chill breh, they gone put you on a list. just kiba and be bool fam, it ain't ya story the most high movin and shakin shyt up rn. stay prayed up hope you a part of the 1/3rd, see ya in the kingdom beloved.that's riiiiiiiiiiiiight!

Here he is below

ABlackMan

Superstar

People don’t see the bigger picture. nikkas getting left behind. Even the affordable electric car won’t be affordable. Really gonna have to have some bread rainy days aheadThese wars might result in everyone finally getting an Electric Vehicle.

Everythingg

King-Over-Kingz

That shyt takes us with them. There is no Wakanda out this bytch.

They’re going to take out 100% of people on the earth?

Been getting beat upside the head for 400+ years and now are like “please don’t let it end this way

”

”If this is how it’s gonna end for them then let it. Strap up and do your best to protect you and yours

Grand Conde

Superstar

This is a bunch of nothing.

bill riser

Pro

Why would Japan be against the US. The US army has japan on lock.Yup WW3 is about to be reeeeeeeeeeeal crazy

Iran, North Korea, Japan, China, Russia

against

UScacs, UKcacs, Frenchcacs, etc

And guest what, you UKRAINE LOVING nikkas are about to be tricked because African countries are about to providing oil and banking for the Opps side….

Im so fukking ready for this. fukk everyone’s world up..

Yeah, the Chinese hate the Japanese something fierce. And I don't blame them considering Japan, to this day, refuses to apologize for the Nanjing Massacre incidentBrehs need to learn history. USA probably the only thing keeping China from pushing Japan shyt in from the stuff they did during WW2

.

.GPBear

The Tape Crusader

Put your embassy on the Iranian border, diplomat brehs

^ yo is this guy still alive ?

^ yo is this guy still alive ?

DeeezNuts

All Star

Whew... i was just there this time last year

The night the US bombed a Chinese embassy

By Kevin Ponniah & Lazara Marinkovic

BBC News, Belgrade

Published

7 May 2019

It was close to midnight and Vlada, a Serbian engineer, was speeding towards his apartment in Belgrade. He had taken his 20-year-old son out that evening but bombs had started to fall across the Yugoslav capital. The power grid was down and he wanted to get home.

Nato, the world's most powerful military alliance, had been pummelling Yugoslavia from the skies since late March to try to bring a halt to atrocities committed by President Slobodan Milosevic's forces against ethnic Albanians in the province of Kosovo. It was now 7 May 1999 and the US-dominated air campaign was only growing more intense.

Vlada's family had spent many nights in recent weeks huddled with others in the basement of their apartment building as air raid sirens blared outside, praying that an errant missile wouldn't strike their homes.

They were lucky, some thought, to live just next to the Chinese embassy - an important diplomatic mission. Being there would surely protect them.

But as Vlada and his son approached the glass doors of their building in the dark, US B-2 stealth warplanes were in the skies above Belgrade. They were locked-on to the precise co-ordinates of a target selected and cleared by the CIA. All Vlada heard at first was the whoosh of an incoming missile. There was no time to move. The doors shattered, spraying glass at them.

"The force of the first bomb lifted us off the ground and we fell… Then one after the other [more bombs landed] - bam, bam, bam. All the shutters on the block were ripped off by the blast, it broke all the windows."

They were terrified but uninjured. All five bombs had hit the embassy, 100 metres away.

The US and Nato were already facing scrutiny over mounting civilian casualties in a bombing campaign conducted without UN authorisation and fiercely opposed by China and Russia. They had now attacked a symbol of Chinese sovereignty in the heart of the Balkans.

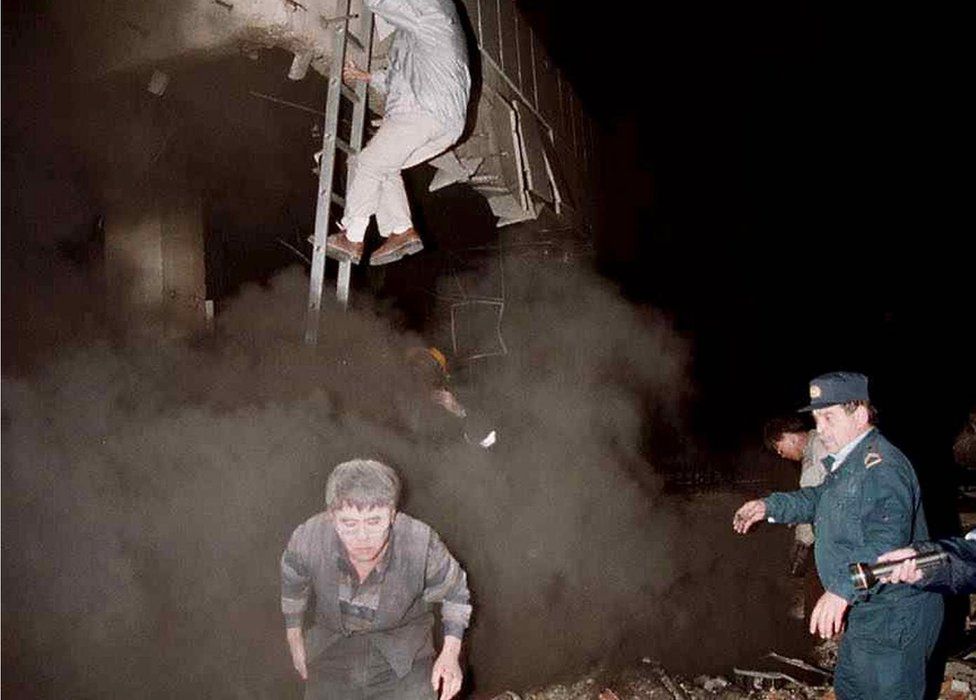

Image caption,

Embassy workers escaped through windows after the strikes

Across town, Shen Hong, a well-connected Chinese businessman, was getting word that the embassy had been hit. He refused to believe it. Just a few days earlier, his father had phoned from Shanghai and joked that his son should park his new Mercedes at the diplomatic compound to keep it safe.

"I called a policeman who I knew and he said, 'Yes, Shen, it's really hit'. He said come right away, so then I knew it was real, it was true."

He arrived to a scene of chaos. The embassy was burning; workers covered in blood and dust were climbing out of windows to escape. Politicians close to Milosevic - who had been charged two weeks earlier with crimes against humanity by an international tribunal - were already arriving to denounce the bombing as the latest example of Nato barbarity.

"We could not go inside. There was a lot of smoke, there wasn't any electricity and we couldn't see anything. It was horrible," said Shen.

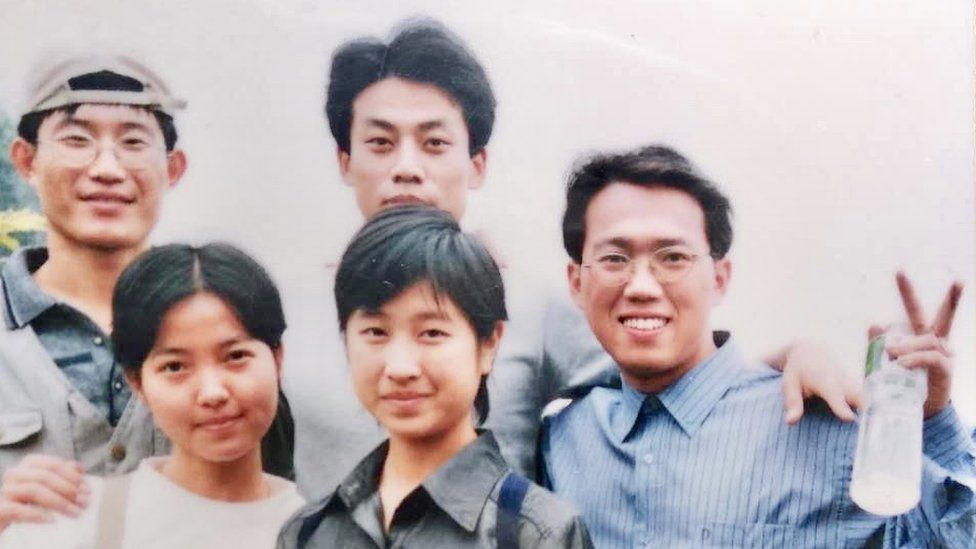

Image caption,

Shen Hong lost close friends in the bombing

He spotted the cultural attaché, a man he knew, who had knotted together curtains to get out of a first-floor window. "We didn't see that he was injured and he didn't notice it either. It was only when I shook his hand that I realised my hands were covered in blood. I told him 'you're injured, you're injured!' - but when he saw this he passed out."

The next day Shen would learn that two close friends - newlywed journalists Xu Xinghu, 31, and Zhu Ying, 27 - had been killed by a bomb that hit the sleeping quarters of the embassy. Their bodies were found under a collapsed wall.

The pair had worked for the Guangming (Enlightenment) Daily - a communist party newspaper. Xu, a language graduate who spoke fluent Serbian, had chronicled life in Belgrade during the bombings in a series of special reports called "Living Under Gunfire".

Zhu Ying worked as an art editor in the paper's advertising department. Her mother collapsed with grief and was sent to hospital when she learned of her daughter's death so Zhu's father travelled alone to Belgrade to see the body.

A third journalist, 48-year-old Shao Yunhuan, of the Xinhua news agency, also died. Her husband, Cao Rongfei, was blinded. The embassy's military attaché, who is believed to have run an intelligence cell from the building, was sent back to China in a coma. In total, three people were killed and at least 20 injured.

For Shen, this was an act of war. The next day he led a protest through the streets of Belgrade carrying a sign reading "NATO: Nazi American Terrorist Organisation"

It was a sign of what was to come.

Image caption,

Three journalists were killed in the embassy

Within hours of the bombing, two competing narratives began to emerge. They would harden over the coming months and form the basis of how the incident - which continues to linger over the US-China relationship - remains debated today.

The bombing fuelled speculation, and there was no shortage of unanswered questions and missing pieces that were put together by some to imply a grand conspiracy. Intrigue continued to hang over the incident and, months afterwards, two respected European newspapers suggested the strikes were by design.

But, as former Nato officials point out, in 20 years no clear evidence has come to light proving what almost all of China believes and America strenuously denies: that it was deliberate.

In those first hours after the bombs fell, the US and Nato wasted no time to announce that it was an accident. China's representative at the UN, meanwhile, denounced a "crime of war" and a "barbarian act".

In Brussels, Jamie Shea - the British Nato spokesman who became the public face of the war - was woken up in the middle of the night and told he would have to face the world's press in the morning. The information available in those early hours was thin but he would give one of the first explanations of what had happened, along with an apology. The warplanes, he said from the briefing podium, had "struck the wrong building".

"It's like a train accident or a car crash - you know what has happened but what you don't know is why it has happened," he says 20 years later. "That took a lot longer to establish… But it was clear right from the get-go, that targeting a foreign embassy was not part of the Nato plan."

Image caption,

The father of Zhu Ying weeps over her coffin in Belgrade

It would take more than a month for the US to give Beijing a full explanation: that a series of basic errors had led to five GPS-guided bombs striking China's embassy - including one that hurtled through the roof of the ambassador's residence next to the main building but didn't explode, likely sparing his life.

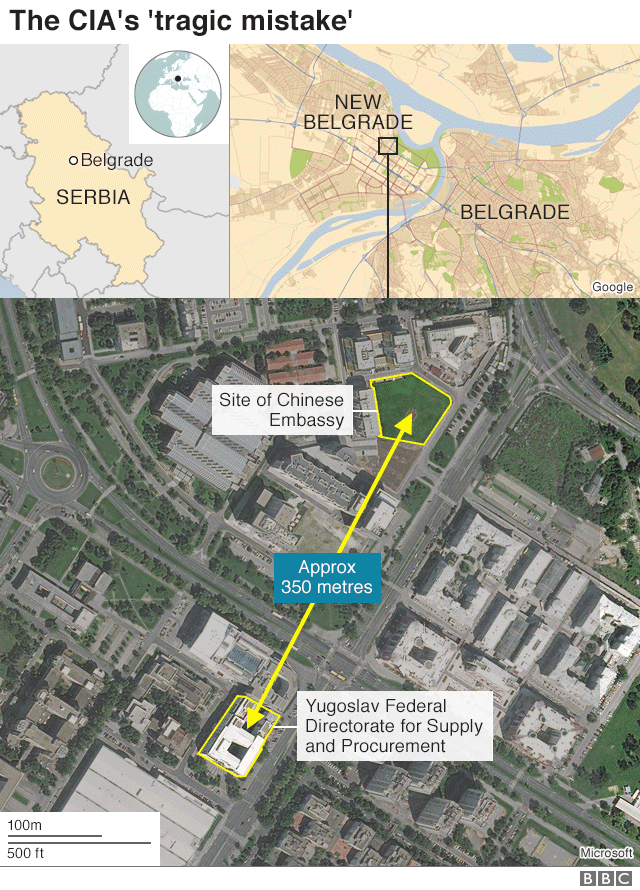

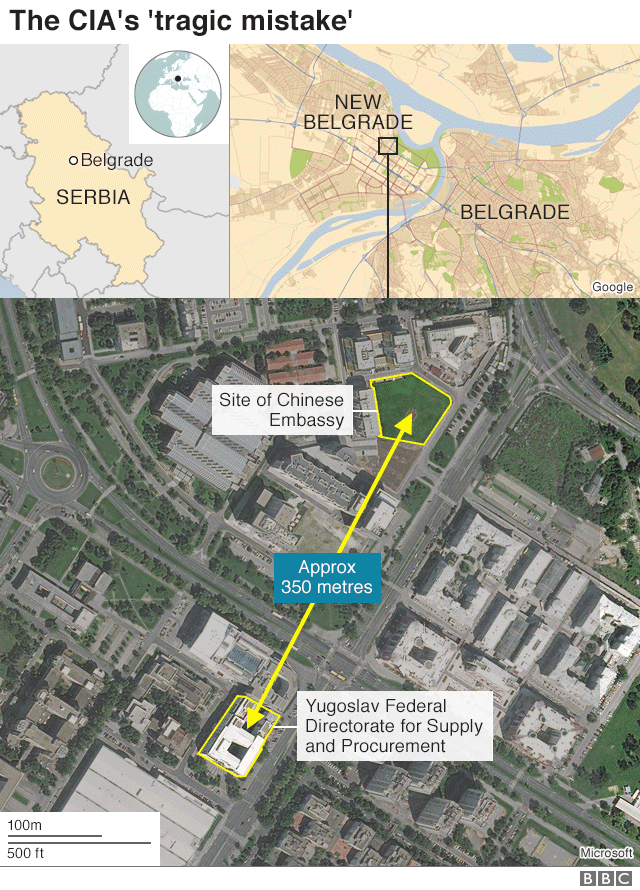

The real target, officials said, was the headquarters of the Yugoslav Federal Directorate for Supply and Procurement (FDSP) - a state agency that imported and exported defence equipment. The grey office building is still there today - hundreds of metres down the road from the embassy site.

Nato had initially hoped the bombing campaign would only last a few days until Milosevic gave up, pulled his forces out of Kosovo and allowed peacekeepers in. But by the time the embassy was hit it had stretched to more than six weeks. In the rush to find hundreds of new targets to sustain the aerial assault, the CIA, which was not normally involved in target-picking, had decided the FDSP should be struck.

But America's premier intelligence agency said it had used a bad map.

"In simple terms, one of our planes attacked the wrong target because the bombing instructions were based on an outdated map," US defence secretary William Cohen said two days after the bombing. He was referring to a US government map that apparently did not show the correct location of the Chinese embassy nor the FDSP.

All US intelligence officers had was an address for the FDSP - 2 Bulevar Umetnosti - and a basic military navigation technique was used to approximate its co-ordinates. The technique used was so imprecise, CIA chief George Tenet later said, that it should never have been used to pick out a target for aerial bombing.

To compound the initial error, Tenet said, intelligence and military databases used to cross-check targets did not have the embassy's new location listed, despite the fact that many US diplomats had actually been inside the building.

Had anyone on the ground visited the site to be bombed they would have found a gated compound, a five-storey building with a green-tiled oriental sloped roof, a bronze plaque announcing the embassy's presence and a large, bright red Chinese flag fluttering more than 10 metres in the air.

IMAGE SOURCE,SASA STANKOVIC/EPA/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

IMAGE SOURCE,SASA STANKOVIC/EPA/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

Image caption,

The front of the embassy was largely undamaged

The crux of the CIA's explanation was hard for many to believe: the world's most advanced military had bombed a fellow UN Security Council member and one of the most vocal opponents of the Nato air campaign because of a mapping error. China was having none of it. The story, it said, was "not convincing".

"The Chinese government and people cannot accept the conclusion that the bombing was a mistake," the foreign minister told a US envoy sent to Beijing in June 1999 to explain what had happened.

But why would the US intentionally attack China?

It wasn't long after the Sun rose on the morning of Saturday, 8 May 1999, that David Rank, a US diplomat, got out of bed in Beijing.

He turned on the television and switched to CNN. The American news network was carrying live pictures of the smouldering Chinese embassy in pitch-dark Belgrade.

By that afternoon, thousands of irate Chinese protesters would be gathered outside. But Rank, at that stage, was fairly calm. He rang his boss, the head of the political section: "I said, you know, Jim, this is the damndest thing."

The diplomat rushed from his residence to the embassy down the road, where US officials were trying to figure out what had happened. Something had clearly gone wrong but this must have been, had to have been, a tragic mistake.

"It was so patently obvious that it was a sort of fog of war accident… At that point I didn't think that down the road this was going to be a major problem. Obviously, it was a major problem, but not the sort of convulsive incident that it turned out to be," said Rank.

But in the next hours, the shape of how the Chinese government and people would respond started to become clear.

IMAGE SOURCE,PETER ROGERS/GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,PETER ROGERS/GETTY IMAGES

Rank began receiving calls from liberal Chinese friends who were outraged at the bombing. American journalists got similar calls from Chinese contacts with pro-US views, expressing shock and a sense of betrayal.

Chinese state media was already laying out a clear narrative - the US had breached international law by bombing a Chinese diplomatic outpost. "The language that I heard from lots and lots of Chinese, it was identical. It was the same almost word-for-word lines of real anger," said Rank.

By that afternoon thousands of students were streaming onto the streets of Beijing. They gathered outside the embassy and things quickly turned violent.

"They were pulling up the paving stones. Beijing sidewalks aren't paved, they have big tiles and they were pulling those up and smashing them and throwing them over the walls."

IMAGE SOURCE,PETER ROGERS/GETTY IMAGES

IMAGE SOURCE,PETER ROGERS/GETTY IMAGES

Many of those bits of concrete were crashing through the windows of a building where more than a dozen embassy staff, including US Ambassador James Sasser, had hunkered down. Embassy cars were being defaced and attacked.

The message was clear: the bombing was intentional and, as one slogan went, "the blood of Chinese must be repaid". The protests would continue the next day, with even more people - some reports said 100,000 - storming the diplomatic district, and pelting stones, paint, eggs and concrete at the British and American embassies.

"We feel like we're hostages," Bill Palmer, an embassy spokesman trapped in one of the buildings, said at the time.

Demonstrations of this scale had not been seen in tightly-controlled China in the decade since students led a pro-democracy uprising in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989. This time the anger was directed away from the Communist Party but, with the 10th anniversary of the crackdown on students in Tiananmen approaching, the government had to strike a balance between giving vent to public anger and remaining in control.

In a rare TV address Vice-President Hu Jintao endorsed the protests but also warned they had to remain "in accordance with the law".

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS

IMAGE SOURCE,REUTERS

Image caption,

US Ambassador James Sasser was trapped in the embassy for four days as protests raged

The uproar was not isolated to Beijing. Crowds also took to the streets of Shanghai and other cities that weekend. In central Chengdu, the US consul's residence was set alight.

Weiping Qin, a then 19-year-old student leader at the maritime college in southern Guangzhou city, said demonstrators were not informed that Nato had already apologised for what it said was an accident. "The government was hiding this important message. They didn't tell us - so young people, everybody, felt angry. We just wanted to go in the streets and protest against the United States."

He said that initially students at his college were told they had to stay in their dormitories. But 24 hours after the bombing, the university leadership told him that they needed 30,000 students in the streets around the US consulate - 500 of whom would come from the maritime college.

The fired-up students drew lots to choose who could attend. They were loaded onto buses and given statements to read that echoed the stilted official language being broadcast by state media. "They gave us long sentences. But in the street, to speak out in long sentences is very hard." He decided to yell slogans about the evils of Nato and the US instead.

IMAGE SOURCE,WEIPING QIN

IMAGE SOURCE,WEIPING QIN

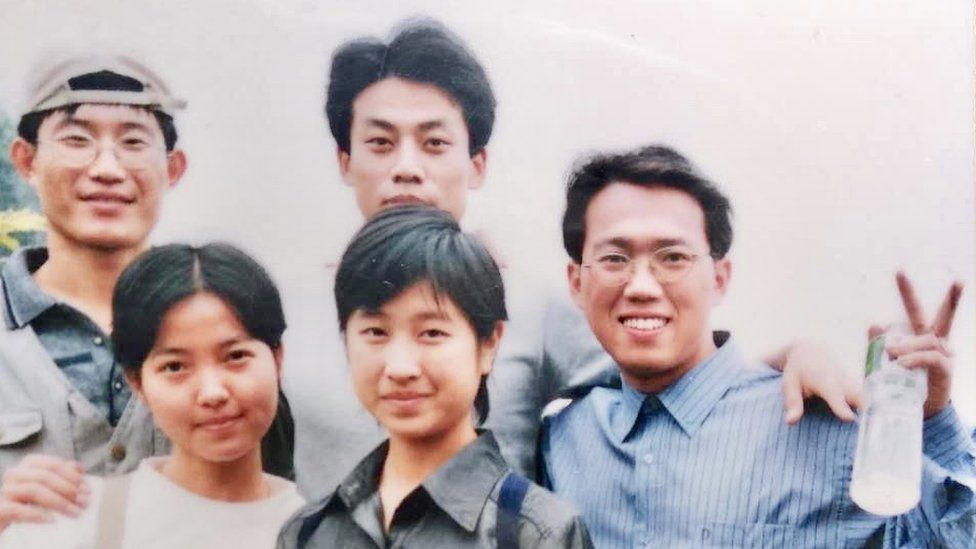

Image caption,

Weiping Qin (right) was a student leader at Guangzhou Maritime College in 1999

The night the US bombed a Chinese embassy

The real target, officials said, was the headquarters of the Yugoslav Federal Directorate for Supply and Procurement (FDSP) - a state agency that imported and exported defence equipment. The grey office building is still there today - hundreds of metres down the road from the embassy site.

Nato had initially hoped the bombing campaign would only last a few days until Milosevic gave up, pulled his forces out of Kosovo and allowed peacekeepers in. But by the time the embassy was hit it had stretched to more than six weeks. In the rush to find hundreds of new targets to sustain the aerial assault, the CIA, which was not normally involved in target-picking, had decided the FDSP should be struck.

But America's premier intelligence agency said it had used a bad map.

"In simple terms, one of our planes attacked the wrong target because the bombing instructions were based on an outdated map," US defence secretary William Cohen said two days after the bombing. He was referring to a US government map that apparently did not show the correct location of the Chinese embassy nor the FDSP.

All US intelligence officers had was an address for the FDSP - 2 Bulevar Umetnosti - and a basic military navigation technique was used to approximate its co-ordinates. The technique used was so imprecise, CIA chief George Tenet later said, that it should never have been used to pick out a target for aerial bombing.

To compound the initial error, Tenet said, intelligence and military databases used to cross-check targets did not have the embassy's new location listed, despite the fact that many US diplomats had actually been inside the building.

Had anyone on the ground visited the site to be bombed they would have found a gated compound, a five-storey building with a green-tiled oriental sloped roof, a bronze plaque announcing the embassy's presence and a large, bright red Chinese flag fluttering more than 10 metres in the air.

Image caption,

The front of the embassy was largely undamaged

The crux of the CIA's explanation was hard for many to believe: the world's most advanced military had bombed a fellow UN Security Council member and one of the most vocal opponents of the Nato air campaign because of a mapping error. China was having none of it. The story, it said, was "not convincing".

"The Chinese government and people cannot accept the conclusion that the bombing was a mistake," the foreign minister told a US envoy sent to Beijing in June 1999 to explain what had happened.

But why would the US intentionally attack China?

It wasn't long after the Sun rose on the morning of Saturday, 8 May 1999, that David Rank, a US diplomat, got out of bed in Beijing.

He turned on the television and switched to CNN. The American news network was carrying live pictures of the smouldering Chinese embassy in pitch-dark Belgrade.

By that afternoon, thousands of irate Chinese protesters would be gathered outside. But Rank, at that stage, was fairly calm. He rang his boss, the head of the political section: "I said, you know, Jim, this is the damndest thing."

The diplomat rushed from his residence to the embassy down the road, where US officials were trying to figure out what had happened. Something had clearly gone wrong but this must have been, had to have been, a tragic mistake.

"It was so patently obvious that it was a sort of fog of war accident… At that point I didn't think that down the road this was going to be a major problem. Obviously, it was a major problem, but not the sort of convulsive incident that it turned out to be," said Rank.

But in the next hours, the shape of how the Chinese government and people would respond started to become clear.

Rank began receiving calls from liberal Chinese friends who were outraged at the bombing. American journalists got similar calls from Chinese contacts with pro-US views, expressing shock and a sense of betrayal.

Chinese state media was already laying out a clear narrative - the US had breached international law by bombing a Chinese diplomatic outpost. "The language that I heard from lots and lots of Chinese, it was identical. It was the same almost word-for-word lines of real anger," said Rank.

By that afternoon thousands of students were streaming onto the streets of Beijing. They gathered outside the embassy and things quickly turned violent.

"They were pulling up the paving stones. Beijing sidewalks aren't paved, they have big tiles and they were pulling those up and smashing them and throwing them over the walls."

Many of those bits of concrete were crashing through the windows of a building where more than a dozen embassy staff, including US Ambassador James Sasser, had hunkered down. Embassy cars were being defaced and attacked.

The message was clear: the bombing was intentional and, as one slogan went, "the blood of Chinese must be repaid". The protests would continue the next day, with even more people - some reports said 100,000 - storming the diplomatic district, and pelting stones, paint, eggs and concrete at the British and American embassies.

"We feel like we're hostages," Bill Palmer, an embassy spokesman trapped in one of the buildings, said at the time.

Demonstrations of this scale had not been seen in tightly-controlled China in the decade since students led a pro-democracy uprising in Beijing's Tiananmen Square in 1989. This time the anger was directed away from the Communist Party but, with the 10th anniversary of the crackdown on students in Tiananmen approaching, the government had to strike a balance between giving vent to public anger and remaining in control.

In a rare TV address Vice-President Hu Jintao endorsed the protests but also warned they had to remain "in accordance with the law".

Image caption,

US Ambassador James Sasser was trapped in the embassy for four days as protests raged

The uproar was not isolated to Beijing. Crowds also took to the streets of Shanghai and other cities that weekend. In central Chengdu, the US consul's residence was set alight.

Weiping Qin, a then 19-year-old student leader at the maritime college in southern Guangzhou city, said demonstrators were not informed that Nato had already apologised for what it said was an accident. "The government was hiding this important message. They didn't tell us - so young people, everybody, felt angry. We just wanted to go in the streets and protest against the United States."

He said that initially students at his college were told they had to stay in their dormitories. But 24 hours after the bombing, the university leadership told him that they needed 30,000 students in the streets around the US consulate - 500 of whom would come from the maritime college.

The fired-up students drew lots to choose who could attend. They were loaded onto buses and given statements to read that echoed the stilted official language being broadcast by state media. "They gave us long sentences. But in the street, to speak out in long sentences is very hard." He decided to yell slogans about the evils of Nato and the US instead.

Image caption,

Weiping Qin (right) was a student leader at Guangzhou Maritime College in 1999

The night the US bombed a Chinese embassy