The Treasury Market Fails a Stress Test

By

Anchalee Worrachate and

Susanne Walker October 30, 2014

Photograph by Brent Lewin/Bloomberg

The Bank of Nova Scotia in Toronto

As soon as Charles Comiskey saw what was happening , he turned off his machines. It was still early in the New York trading day on Oct. 15, and investors were already shifting billions of dollars into U.S. government bonds as global markets from Asia to Europe buckled. Because prices were rising and yields falling so rapidly, Comiskey, the head Treasury dealer at Bank of Nova Scotia (

BNS:CN), realized that he ran the risk of being stuck with losses or unwanted inventory if his computers automatically generated quotes to buy and sell.

“Once we recognized things started getting out of control, we shut it off immediately,” he says. For about half an hour he executed client orders individually over the phone. “It was a very high-stress, very fearful trade,” says Comiskey, whose firm is one of 22 primary dealers that trade government bonds directly with the Federal Reserve. “It was like turning the clocks back to pre-electronic trading” in the 1990s.

Bank of Nova Scotia’s need to protect itself during volatile trading shows that, in part because of new regulations meant to make banks safer, even the Treasury market can wobble under stress. Treasuries are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, and the $12.3 trillion market is the world’s biggest for government debt, exceeding the size of the next two nations’ combined. Those factors have made Treasuries a haven for investors during times of turmoil: Not only are they safe, but they are also liquid—Treasuries can be bought and sold in large volume more quickly and efficiently than any other asset. During the credit crisis in 2008, Treasury prices soared 14 percent, while both investment-grade and junk-rated corporate debt prices sank.

Story: Who's Afraid of a Stress Test?

To comply with higher capital requirements adopted by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the international regulatory group, banks with bond trading desks have reduced inventories. Primary dealers have slashed their U.S. debt holdings 56 percent, to $64 billion, from a high in October 2013, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

At the same time, supply is being constrained by the trillions of dollars in U.S. bonds that central banks from the Fed to the Bank of Japan (

8301:JP) bought to support their economies. What happened on Oct. 15 “was another manifestation of the world we live in after the Lehman crisis,” says Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, a strategist at JPMorgan Chase (

JPM), a primary dealer. “Liquidity dries up quickly when volatility spikes. No market is immune to that anymore.”

Gripped by concern about another recession in Europe, slowing economic growth in China, and the spread of the Ebola outbreak, investors scrambled to stash their money in Treasuries on Oct. 15. Dealers contended with the onslaught by offering fewer bonds at a given price. They also demanded wider spreads—the gap between the price they’d pay for a bond and the price they’d sell it for. That made trading more expensive for investors. “There’s a thin line to keeping the customer happy while also giving a level that you can at least get out of without taking a big loss right away,” says Jason Rogan, managing director of U.S. government trading at Guggenheim Securities, which isn’t a primary dealer. Guggenheim turned off its automated pricing on Oct. 15, because “the market was moving too fast for our prices to keep up,” he says.

Story: Charlie Rose Talks to Treasury Secretary Jack Lew

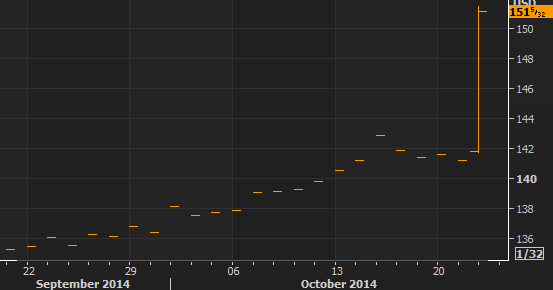

Trading volume on Oct. 15 rose to a record—$946 billion of U.S. government debt changed hands through ICAP (

IAP:LN), the largest interdealer broker—and prices swung wildly. Yields on the 10-year note tumbled to a low of 1.86 percent that day, with most of the drop occurring in a 10-minute period beginning at 9:30 a.m. in New York, before ending the day at 2.14 percent. (Yields rise when prices fall and fall when prices rise.) Adjusted for current yields, the magnitude of the decline during trading on Oct. 15 has been exceeded only once in the past half-century, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The volatility raised concerns among market participants that trading could be even more chaotic when the Fed begins to raise rates from their near-zero levels and investors rush to adjust their portfolios. “The market could not handle large flows without prices moving massively,” Michael Cloherty, head of U.S. rates strategy at RBC Capital Markets (

RY), said in an e-mail. “We took that test Oct. 15 and failed.”

This is a big problem.

that UPS tip

that UPS tip

@ this picture.

@ this picture.