You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Another Big Win For Putin!!!

- Thread starter 88m3

- Start date

-

- Tags

- putin russia vladimir world news

More options

Who Replied?TheDarkskinnedDrake

All Star

I'm glad I've found this thread

two incredible articles:

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

ADevilYouKhow

Rhyme Reason

ill

Superstar

88m3

Fast Money & Foreign Objects

Putin’s Economy Is Stuck and He Doesn’t Know How to Get It Going

Evgenia Pismennaya

Ilya Arkhipov world_reporter

July 31, 2016 — 10:00 PM EDT

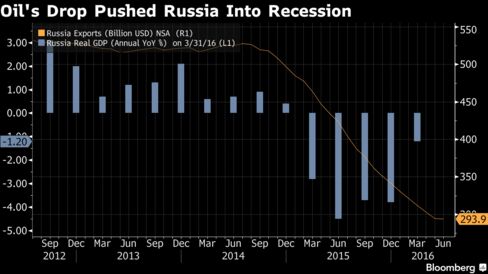

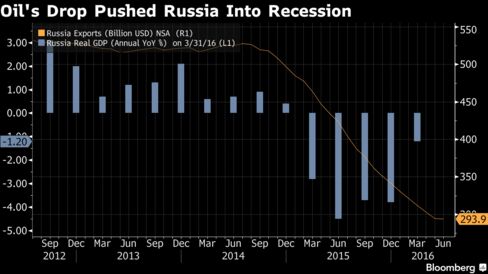

Vladimir Putin’s economy has been shrinking for 18 months but he still doesn’t have a plan to get it going again.

QUICKTAKEVladimir Putin

After focusing almost exclusively on foreign policy since early 2014, the need to get the economy back into gear is forcing the Russian president to face a painful choice: bow to the demands of the markets or protect his Kremlin-centered system.

“Putin makes political and geopolitical decisions confidently, but delays on the economic ones because they are harder for him,” said Yevgeny Yasin, a former economy minister. “Serious, decisive measures are needed” to get the economy out of its current stagnation, he said. “But I get the feeling the president isn’t ready for them.”

The worst of the contraction -- the longest of Putin’s 16-year rule -- appears over. But even Kremlin officials admit there’s no sign of anything on the horizon to drive much of a rebound, barring a jump in oil prices, something few forecasters expect.

Seeking Advice

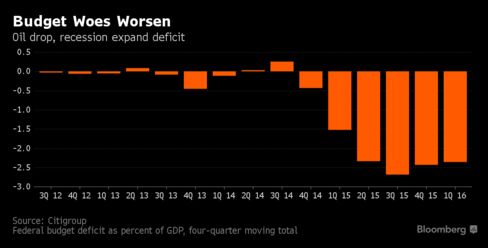

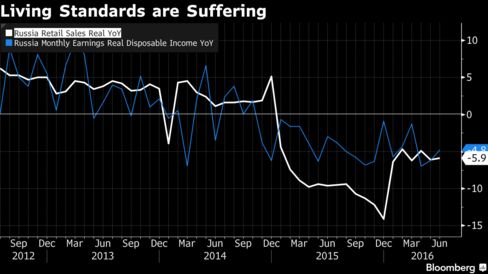

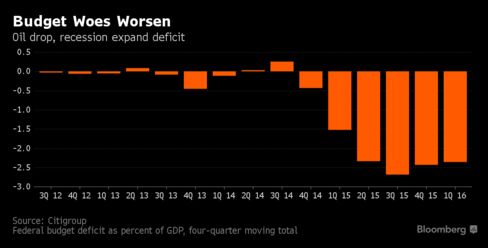

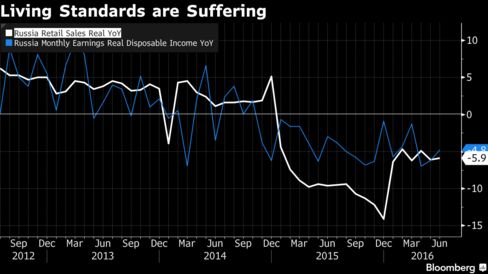

Low crude prices have cut deeply into government revenues and U.S. and European Union sanctions have limited access to capital, putting out of reach the kind of stimulus that got the economy back on track after the last recession in 2009. The central bank says there’s no room to ease credit quickly, either, with inflation over 7 percent. Businesses and consumers are still cutting spending.

For a Quicktake explainer on the political impact of Putin’s economic troubles, click here.

In the last few months, Putin has convened a pair of high-level advisory panels to come up with ideas to accelerate the economy. He says he’s targeting growth of 4 percent a year, well above the 1.2 percent economists expect next year. That’s still far below the rates seen during his first two terms in 2000-2008, when surging oil prices pushed the economy into overdrive. Continued stagnation is also a threat to his geopolitical ambitions, as it leaves less to spend on a big military buildup.

Divisions have already appeared between the wide range of specialists pitching ideas on how to revive the economy, according to officials and others involved in the process. That’s in contrast to his handling of the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, where he has relied on a tight circle of his closest aides for counsel.

The most prominent of the economic advisers is Alexei Kudrin, credited with laying the foundations for fiscal stability as finance minister from 2000-2011. His appointment in April to a top role on one of the Kremlin panels raised hopes that Putin might back Kudrin’s calls for reducing state control over the economy to stimulate private business and cutting the budget deficit to bring down inflation. The International Monetary Fund endorsed that recipe in its annual review of Russian economic policy earlier this month.

Magic Wand

But so far, the president seems to be seeking more of a magic wand to get the economy again, much as surging oil prices did in the mid-2000s, the people involved in the discussion said. The kinds of steps Kudrin has proposed risk alienating powerful people in state-run businesses by reining in their reach and undermining public support if government spending is cut. Both are risky as Putin heads into elections in 2018.

“They can write a radical program that’s politically impossible, but then all that will be taken from it is what will work. The rest they won’t take,” said Oleg Vyugin, a former top central bank and finance ministry official who also sits on one of the Kremlin advisory panels. “Kudrin has been given a mandate, but for the moment, it’s not worth anything,”

In his latest role, Kudrin has been assigned only to craft a program for Putin’s next presidential term. His efforts to broaden the mandate to include current policy have so far been blocked, according to senior officials. Last year, he discussed taking a top Kremlin or government job with Putin, but couldn’t agree on broad enough powers.

The Kudrin panel “is first of all about theory,” said Alexey Repik, an entrepreneur and business lobbyist who is a member of both the advisory groups.

Putin has ordered a group of economists who back what they’ve dubbed “quantitative easing, Russian-style,” to prepare a detailed program based on their proposal for a 1.5-trillion-ruble ($22.5 billion) annual stimulus plan. Their state-led investment plan is the opposite of Kudrin’s call for controlling government spending to allow the private sector to drive growth.

Putin is likely to cherry-pick ideas from the rival camps to minimize public discontent and keep key elite groups happy rather adopt a broader strategy, the people involved in the process said. The result can seem contradictory. Privatizations this year, for example, were supposed to reduce the government’s role in the economy. But major state-owned companies and funds have emerged among the potential bidders for some of the assets.

The second panel Putin set up, a special commission on “priority projects” to help boost growth in the short term, is relying on the kind of top-down direction the Kremlin has long favored.

“The priority is national projects, for which the money still has to be found,” said Sergey Dubinin, a former central bank chief who’s now on the board of VTB Bank. “And priorities like that require manual control,” he added, referring to the kind of heavy-handed state management that pro-market economists like Kudrin argue is a major barrier to growth.

A Bloomberg survey of economists found that most thought oil would have to stay below $40 a barrel for an extended period in order to force the Kremlin into politically painful changes.

When Putin named him to the advisory role this spring, Kudrin said he would push for aggressive overhauls. “My goal is to show that there won’t be economic growth if we don’t reform institutions,” he said in May. Putin’s reaction to the proposals was cool, according to participants in a Kremlin meeting at the time. He rejected any suggestion that he should make concessions to reduce tensions with the West in an effort to ease economic pressure.

“Putin has an awful lot of other concerns,” said Boris Titov, who heads a business lobby and attended the advisory panel session with Kudrin in May. “Even at that meeting, he talked mostly about foreign policy.”

Putin’s Economy Is Stuck and He Doesn’t Know How to Get It Going

Evgenia Pismennaya

Ilya Arkhipov world_reporter

July 31, 2016 — 10:00 PM EDT

- President seen cherry-picking proposals from Kudrin, others

- Kudrin’s mandate as adviser said limited to post-2018 plans

Vladimir Putin’s economy has been shrinking for 18 months but he still doesn’t have a plan to get it going again.

QUICKTAKEVladimir Putin

After focusing almost exclusively on foreign policy since early 2014, the need to get the economy back into gear is forcing the Russian president to face a painful choice: bow to the demands of the markets or protect his Kremlin-centered system.

“Putin makes political and geopolitical decisions confidently, but delays on the economic ones because they are harder for him,” said Yevgeny Yasin, a former economy minister. “Serious, decisive measures are needed” to get the economy out of its current stagnation, he said. “But I get the feeling the president isn’t ready for them.”

The worst of the contraction -- the longest of Putin’s 16-year rule -- appears over. But even Kremlin officials admit there’s no sign of anything on the horizon to drive much of a rebound, barring a jump in oil prices, something few forecasters expect.

Seeking Advice

Low crude prices have cut deeply into government revenues and U.S. and European Union sanctions have limited access to capital, putting out of reach the kind of stimulus that got the economy back on track after the last recession in 2009. The central bank says there’s no room to ease credit quickly, either, with inflation over 7 percent. Businesses and consumers are still cutting spending.

For a Quicktake explainer on the political impact of Putin’s economic troubles, click here.

In the last few months, Putin has convened a pair of high-level advisory panels to come up with ideas to accelerate the economy. He says he’s targeting growth of 4 percent a year, well above the 1.2 percent economists expect next year. That’s still far below the rates seen during his first two terms in 2000-2008, when surging oil prices pushed the economy into overdrive. Continued stagnation is also a threat to his geopolitical ambitions, as it leaves less to spend on a big military buildup.

Divisions have already appeared between the wide range of specialists pitching ideas on how to revive the economy, according to officials and others involved in the process. That’s in contrast to his handling of the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, where he has relied on a tight circle of his closest aides for counsel.

The most prominent of the economic advisers is Alexei Kudrin, credited with laying the foundations for fiscal stability as finance minister from 2000-2011. His appointment in April to a top role on one of the Kremlin panels raised hopes that Putin might back Kudrin’s calls for reducing state control over the economy to stimulate private business and cutting the budget deficit to bring down inflation. The International Monetary Fund endorsed that recipe in its annual review of Russian economic policy earlier this month.

Magic Wand

But so far, the president seems to be seeking more of a magic wand to get the economy again, much as surging oil prices did in the mid-2000s, the people involved in the discussion said. The kinds of steps Kudrin has proposed risk alienating powerful people in state-run businesses by reining in their reach and undermining public support if government spending is cut. Both are risky as Putin heads into elections in 2018.

“They can write a radical program that’s politically impossible, but then all that will be taken from it is what will work. The rest they won’t take,” said Oleg Vyugin, a former top central bank and finance ministry official who also sits on one of the Kremlin advisory panels. “Kudrin has been given a mandate, but for the moment, it’s not worth anything,”

In his latest role, Kudrin has been assigned only to craft a program for Putin’s next presidential term. His efforts to broaden the mandate to include current policy have so far been blocked, according to senior officials. Last year, he discussed taking a top Kremlin or government job with Putin, but couldn’t agree on broad enough powers.

The Kudrin panel “is first of all about theory,” said Alexey Repik, an entrepreneur and business lobbyist who is a member of both the advisory groups.

Putin has ordered a group of economists who back what they’ve dubbed “quantitative easing, Russian-style,” to prepare a detailed program based on their proposal for a 1.5-trillion-ruble ($22.5 billion) annual stimulus plan. Their state-led investment plan is the opposite of Kudrin’s call for controlling government spending to allow the private sector to drive growth.

Putin is likely to cherry-pick ideas from the rival camps to minimize public discontent and keep key elite groups happy rather adopt a broader strategy, the people involved in the process said. The result can seem contradictory. Privatizations this year, for example, were supposed to reduce the government’s role in the economy. But major state-owned companies and funds have emerged among the potential bidders for some of the assets.

The second panel Putin set up, a special commission on “priority projects” to help boost growth in the short term, is relying on the kind of top-down direction the Kremlin has long favored.

“The priority is national projects, for which the money still has to be found,” said Sergey Dubinin, a former central bank chief who’s now on the board of VTB Bank. “And priorities like that require manual control,” he added, referring to the kind of heavy-handed state management that pro-market economists like Kudrin argue is a major barrier to growth.

A Bloomberg survey of economists found that most thought oil would have to stay below $40 a barrel for an extended period in order to force the Kremlin into politically painful changes.

When Putin named him to the advisory role this spring, Kudrin said he would push for aggressive overhauls. “My goal is to show that there won’t be economic growth if we don’t reform institutions,” he said in May. Putin’s reaction to the proposals was cool, according to participants in a Kremlin meeting at the time. He rejected any suggestion that he should make concessions to reduce tensions with the West in an effort to ease economic pressure.

“Putin has an awful lot of other concerns,” said Boris Titov, who heads a business lobby and attended the advisory panel session with Kudrin in May. “Even at that meeting, he talked mostly about foreign policy.”

Putin’s Economy Is Stuck and He Doesn’t Know How to Get It Going

ill

Superstar

Not even Russian related but the only people that will care are in here. @88m3 @ThreeLetterAgency

Check this out. Talks about Pakistani intelligence and their proxy war in Afghanistan against India. Nap, a few of your favorite villains are in here.

WikiLeaks - Hillary Clinton Email Archive

Check this out. Talks about Pakistani intelligence and their proxy war in Afghanistan against India. Nap, a few of your favorite villains are in here.

WikiLeaks - Hillary Clinton Email Archive