get these nets

Veteran

Venezuelans Say Most Of Guyana Is Theirs. Guyanese Call That A 'Jumbie' Story

September 14, 2021

Ariana Cubillo

/

Venezuela's regime and opposition are repeating a century-old claim that three-fourths of Guyana belongs to their country. Is it valid — or nationalist nonsense?

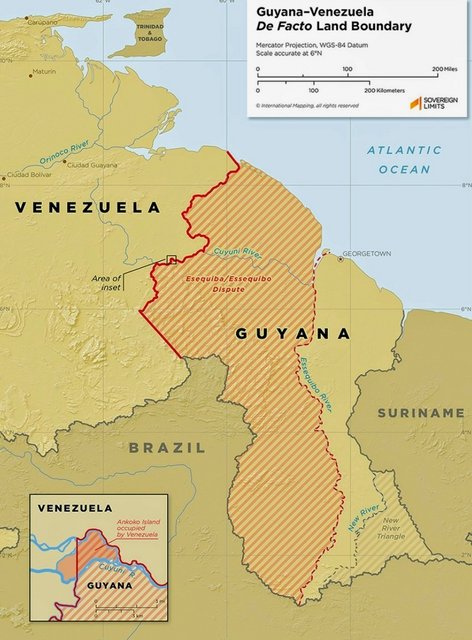

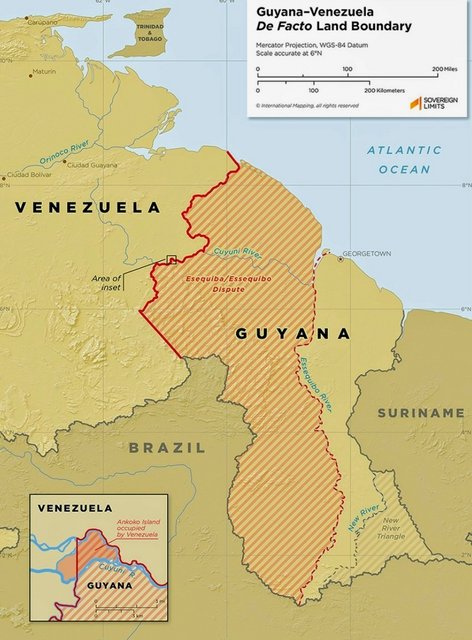

For more than a century, Venezuela and Guyana have been arguing about where their border should be — or at least Venezuela has.

Last week, that long-running territorial dispute erupted again when Venezuela’s regime — and even its political opposition — issued an unusual joint statement insisting that three-fourths of Guyana actually belongs to Venezuela.

Guyana angrily called Venezuela's latest turf declaration “an overt threat to [our] sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

“The claim by Venezuela on Guyana is not only absurd in terms of the basis of the claim but in terms of the size of the claim,” said Carl Greenidge, a former vice president of Guyana and the agent representing the country in this case at the U.N.'s International Court of Justice, or World Court, in the Hague.

"It is not a logical story."

It is, at least, to most Venezuelans. Look at any map of Venezuela — notably, any map made in Venezuela. It includes an appendage called zona en reclamación — "zone in reclamation." It includes 61,000 square miles of Guyana west of the Essequibo River, or El Esequibo in Spanish.

"In school they would take points off if we didn't draw the Esequibo [territory] lines on the Venezuelan map," recalled Maria Alejandra Marquez, who grew up in Venezuela convinced that region of Guyana belonged to her country.

"If you asked me to draw a map of Venezuela on a napkin right now, I would include it."

Marquez is a Venezuelan exile and entrepreneur in Miami — and no fan of Venezuela's authoritarian socialist regime. In fact, she heads a nonprofit, INRAV, that helps recover allegedly corrupt assets from that regime. Still, she understands Venezuela's efforts to regain the Esequibo tract.

She remembers in the 1980s, when she was a teenager, the Venezuelan rock band Témpano scored a hit with a nationalistic song called "El Esequibo." The chorus shouted: “The Esequibo is mine, it’s yours, it’s Venezuelan land!”

“Then in my early 20s I went to study in England," Marquez said, "and realizing that nobody else outside Venezuela would include El Esequibo in the Venezuelan map was a shock.”

A shock for the Venezuelan diaspora, too.

“If you go to a rally in Miami about Venezuelan issues, you will see people selling stuff with the map of Venezuela including that," Marquez noted, "because we’ve been socialized, educated to understand there was an abuse of power to take it away from us.”

Maria Alejandra Marquez

That abuse of power, they argue, occurred in 1899 — and the alleged abuser was Great Britain, which at that time held Guyana as a colony, British Guiana.

In the late 19th century, Venezuela and British Guiana were at odds about their border. So, in 1899, international arbitrators set the map lines as we know them today.

But since then most Venezuelans have insisted the agreement wasn't valid because they believe the arbitrators favored the powerful British Empire — that the accord was imposed on the young Venezuelan republic by bullying imperialists.

"For Venezuelans that treaty never really happened," said Luis Vicente León, a Venezuelan political expert and president of the Caracas polling firm Datanálisis.

"They believe the arbitrators cheated Venezuela out of the Esequibo territory that went to Guyana."

The claim by Venezuela on Guyana is not only absurd in terms of the basis of the claim but in terms of the size of the claim.

Carl Greenidge

For most Venezuelans the 1899 Venezuela-Guyana border treaty never really happened. They believe imperialist arbitrators cheated Venezuela out of the territory that went to Guyana.

Luis Vicente Leon

To back that up, Venezuelans point to a memo from one of Venezuela's 1899 arbitration counselors, U.S. lawyer Severo Mallet-Prevost. His colleagues claimed he told them not to read the note until after he died. When they opened it in 1949, they said it revealed Mallet-Prevost did feel Venezuelan had been cheated.

But the Guyanese have a word for that memo:

“A jumbie story," said Wesley Kirton, a former Guyanese diplomat who today heads the Guyanese-American Chamber of Commerce in Miami.

A "jumbie" is a sort of bogus ghost story meant to scare people. But Kirton says the bigger scare tactic — and the real reason Venezuela kept claiming Guyana’s Esequibo territory — was the Cold War. That is, the Red Scare.

JFK IN CARACAS

“Because of the emergence of Fidel Castro in Cuba in the early 1960s," Kirton said, "the Americans at the time, in order to stem the possible flow of communism, encouraged Venezuela to advance this claim against Guyana.”

President John F. Kennedy did visit Caracas in 1961 — and recently declassified memos indicate his administration did urge Venezuela to ramp up its demand for the Esequibo.

That’s because British Guiana’s chief minister at the time — Cheddi Jagan — was a leftist and a Castro sympathizer. British Guiana was moving toward independence from Britain, but the U.S. didn’t want a Castro ally leading a new Latin American country. It hoped that stoking the Venezuela-Guiana border dispute would delay Guiana’s independence until Jagan could be defeated at the polls.

And it apparently worked.

“Jagan, in 1964, lost the election to a more America-friendly party," Kirton points out.

Wesley Kirton

POLITICS AND OIL

But meanwhile, Venezuela’s nationalist fervor about its claim to the Guyanese territory had been rekindled.

“It was always kept on the psyche of the Venezuelans," Kirton said.

So, shortly before Guyana became independent in 1966, it agreed to let the United Nations host periodic discussions with Venezuela about the 1899 border settlement. But why, five decades later, has Venezuela suddenly become so aggressive about demanding three-quarters of a neighboring country?

Two reasons: Domestic politics. And oil.

In 2015, ExxonMobil discovered potentially billions of barrels of crude oil off Guyana’s coast — offshore waters that are also part of Venezuela’s territorial claim in Guyana.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro seized on that to divert attention from — if not create a scapegoat for — his country’s catastrophic economic collapse, for which he and his socialist regime are widely blamed. Now, he said, Venezuela was also being cheated out of oil wealth in Guyana. He went to the National Assembly and said the dispute had been dialed up to a “high-intensity conflict.”

Maduro even started rattling sabers, using his navy to harass Guyanese and ExxonMobil ships — and Guyanese fishing boats earlier this year. That's raised concerns in South America and the Caribbean about a diplomatic fracas morphing into a military one.

So the U.N. threw the Venezuela-Guyana border issue to the World Court in 2018. A ruling is expected in a few years.

An ExxonMobil oil exploration and drilling ship, painted with Guyana's colors, in waters off Guyana.

But last week's Venezuelan declaration brought a new dimension to the controversy.

Maduro's regime and the Venezuelan opposition — led by Juan Guaidó, whom the U.S. and almost 60 other countries recognize as Venezuela's constitutionally-legitimate president — are in contentious political reform talks in Mexico City. Their joint statement on Venezuela's right to Guyana's Esequibo territory was a rare point of agreement that observers say was meant to create some common ground.

But the Guyanese saw it as an underhanded move by both Venezuelan sides.

"Guayana cannot be used as an altar of sacrifice for settlement of Venezuela's internal political difference," the government said. "While [Guyana] welcomes domestic accord within Venezuela, an agreement defying international law and process is not a basis for mediating harmony."

Still, says León at Datanálisis in Caracas, no Venezuelan politician would ever dare question the country's Guyana claim — leaving Guaidó and the opposition little choice but to join Maduro.

Kirton insists Guyanese are even more resolved not to back down now.

"We have a sense of nationalism and national pride too," he said. "Guyana shouldn't be robbed of any of its land mass or maritime space — particularly at this time," he added, after the recent oil finds, "when we see the economic potential that we were yearning for for years."

Which is a reminder that Venezuela faces not just a high legal hurdle in this case but also international public opinion.

A century ago Venezuela could say it was the small underdog facing the British empire. Today the roles seem reversed. Guyana is, in fact, four times smaller in size than Venezuela; its gross domestic product is also eight times smaller.

“Guyana is the party that now confronts a power that is far greater than Guyana,” said Greenidge, the Guyanese diplomat representing Guyana at the World Court, from Guyana's capital of Georgetown.

“As a tiny state we have no protection. Therefore we have an interest in international law and order being respected.”

If the World Court rules in Guyana’s favor, it seems unlikely Venezuela — which questions the court's jurisdiction in the case — will accept it. Because for Venezuelans, for more than a hundred years, this isn’t just about international law, but nationalist emotion.

September 14, 2021

Ariana Cubillo

/

Venezuela's regime and opposition are repeating a century-old claim that three-fourths of Guyana belongs to their country. Is it valid — or nationalist nonsense?

For more than a century, Venezuela and Guyana have been arguing about where their border should be — or at least Venezuela has.

Last week, that long-running territorial dispute erupted again when Venezuela’s regime — and even its political opposition — issued an unusual joint statement insisting that three-fourths of Guyana actually belongs to Venezuela.

Guyana angrily called Venezuela's latest turf declaration “an overt threat to [our] sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

“The claim by Venezuela on Guyana is not only absurd in terms of the basis of the claim but in terms of the size of the claim,” said Carl Greenidge, a former vice president of Guyana and the agent representing the country in this case at the U.N.'s International Court of Justice, or World Court, in the Hague.

"It is not a logical story."

It is, at least, to most Venezuelans. Look at any map of Venezuela — notably, any map made in Venezuela. It includes an appendage called zona en reclamación — "zone in reclamation." It includes 61,000 square miles of Guyana west of the Essequibo River, or El Esequibo in Spanish.

"In school they would take points off if we didn't draw the Esequibo [territory] lines on the Venezuelan map," recalled Maria Alejandra Marquez, who grew up in Venezuela convinced that region of Guyana belonged to her country.

"If you asked me to draw a map of Venezuela on a napkin right now, I would include it."

Marquez is a Venezuelan exile and entrepreneur in Miami — and no fan of Venezuela's authoritarian socialist regime. In fact, she heads a nonprofit, INRAV, that helps recover allegedly corrupt assets from that regime. Still, she understands Venezuela's efforts to regain the Esequibo tract.

She remembers in the 1980s, when she was a teenager, the Venezuelan rock band Témpano scored a hit with a nationalistic song called "El Esequibo." The chorus shouted: “The Esequibo is mine, it’s yours, it’s Venezuelan land!”

“Then in my early 20s I went to study in England," Marquez said, "and realizing that nobody else outside Venezuela would include El Esequibo in the Venezuelan map was a shock.”

A shock for the Venezuelan diaspora, too.

“If you go to a rally in Miami about Venezuelan issues, you will see people selling stuff with the map of Venezuela including that," Marquez noted, "because we’ve been socialized, educated to understand there was an abuse of power to take it away from us.”

Maria Alejandra Marquez

That abuse of power, they argue, occurred in 1899 — and the alleged abuser was Great Britain, which at that time held Guyana as a colony, British Guiana.

In the late 19th century, Venezuela and British Guiana were at odds about their border. So, in 1899, international arbitrators set the map lines as we know them today.

But since then most Venezuelans have insisted the agreement wasn't valid because they believe the arbitrators favored the powerful British Empire — that the accord was imposed on the young Venezuelan republic by bullying imperialists.

"For Venezuelans that treaty never really happened," said Luis Vicente León, a Venezuelan political expert and president of the Caracas polling firm Datanálisis.

"They believe the arbitrators cheated Venezuela out of the Esequibo territory that went to Guyana."

The claim by Venezuela on Guyana is not only absurd in terms of the basis of the claim but in terms of the size of the claim.

Carl Greenidge

For most Venezuelans the 1899 Venezuela-Guyana border treaty never really happened. They believe imperialist arbitrators cheated Venezuela out of the territory that went to Guyana.

Luis Vicente Leon

To back that up, Venezuelans point to a memo from one of Venezuela's 1899 arbitration counselors, U.S. lawyer Severo Mallet-Prevost. His colleagues claimed he told them not to read the note until after he died. When they opened it in 1949, they said it revealed Mallet-Prevost did feel Venezuelan had been cheated.

But the Guyanese have a word for that memo:

“A jumbie story," said Wesley Kirton, a former Guyanese diplomat who today heads the Guyanese-American Chamber of Commerce in Miami.

A "jumbie" is a sort of bogus ghost story meant to scare people. But Kirton says the bigger scare tactic — and the real reason Venezuela kept claiming Guyana’s Esequibo territory — was the Cold War. That is, the Red Scare.

JFK IN CARACAS

“Because of the emergence of Fidel Castro in Cuba in the early 1960s," Kirton said, "the Americans at the time, in order to stem the possible flow of communism, encouraged Venezuela to advance this claim against Guyana.”

President John F. Kennedy did visit Caracas in 1961 — and recently declassified memos indicate his administration did urge Venezuela to ramp up its demand for the Esequibo.

That’s because British Guiana’s chief minister at the time — Cheddi Jagan — was a leftist and a Castro sympathizer. British Guiana was moving toward independence from Britain, but the U.S. didn’t want a Castro ally leading a new Latin American country. It hoped that stoking the Venezuela-Guiana border dispute would delay Guiana’s independence until Jagan could be defeated at the polls.

And it apparently worked.

“Jagan, in 1964, lost the election to a more America-friendly party," Kirton points out.

Wesley Kirton

POLITICS AND OIL

But meanwhile, Venezuela’s nationalist fervor about its claim to the Guyanese territory had been rekindled.

“It was always kept on the psyche of the Venezuelans," Kirton said.

So, shortly before Guyana became independent in 1966, it agreed to let the United Nations host periodic discussions with Venezuela about the 1899 border settlement. But why, five decades later, has Venezuela suddenly become so aggressive about demanding three-quarters of a neighboring country?

Two reasons: Domestic politics. And oil.

In 2015, ExxonMobil discovered potentially billions of barrels of crude oil off Guyana’s coast — offshore waters that are also part of Venezuela’s territorial claim in Guyana.

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro seized on that to divert attention from — if not create a scapegoat for — his country’s catastrophic economic collapse, for which he and his socialist regime are widely blamed. Now, he said, Venezuela was also being cheated out of oil wealth in Guyana. He went to the National Assembly and said the dispute had been dialed up to a “high-intensity conflict.”

Maduro even started rattling sabers, using his navy to harass Guyanese and ExxonMobil ships — and Guyanese fishing boats earlier this year. That's raised concerns in South America and the Caribbean about a diplomatic fracas morphing into a military one.

So the U.N. threw the Venezuela-Guyana border issue to the World Court in 2018. A ruling is expected in a few years.

An ExxonMobil oil exploration and drilling ship, painted with Guyana's colors, in waters off Guyana.

But last week's Venezuelan declaration brought a new dimension to the controversy.

Maduro's regime and the Venezuelan opposition — led by Juan Guaidó, whom the U.S. and almost 60 other countries recognize as Venezuela's constitutionally-legitimate president — are in contentious political reform talks in Mexico City. Their joint statement on Venezuela's right to Guyana's Esequibo territory was a rare point of agreement that observers say was meant to create some common ground.

But the Guyanese saw it as an underhanded move by both Venezuelan sides.

"Guayana cannot be used as an altar of sacrifice for settlement of Venezuela's internal political difference," the government said. "While [Guyana] welcomes domestic accord within Venezuela, an agreement defying international law and process is not a basis for mediating harmony."

Still, says León at Datanálisis in Caracas, no Venezuelan politician would ever dare question the country's Guyana claim — leaving Guaidó and the opposition little choice but to join Maduro.

Kirton insists Guyanese are even more resolved not to back down now.

"We have a sense of nationalism and national pride too," he said. "Guyana shouldn't be robbed of any of its land mass or maritime space — particularly at this time," he added, after the recent oil finds, "when we see the economic potential that we were yearning for for years."

Which is a reminder that Venezuela faces not just a high legal hurdle in this case but also international public opinion.

A century ago Venezuela could say it was the small underdog facing the British empire. Today the roles seem reversed. Guyana is, in fact, four times smaller in size than Venezuela; its gross domestic product is also eight times smaller.

“Guyana is the party that now confronts a power that is far greater than Guyana,” said Greenidge, the Guyanese diplomat representing Guyana at the World Court, from Guyana's capital of Georgetown.

“As a tiny state we have no protection. Therefore we have an interest in international law and order being respected.”

If the World Court rules in Guyana’s favor, it seems unlikely Venezuela — which questions the court's jurisdiction in the case — will accept it. Because for Venezuelans, for more than a hundred years, this isn’t just about international law, but nationalist emotion.

Uncle Sam was really doing a lot back in the day.

Uncle Sam was really doing a lot back in the day.