IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Basically a variety of songs of afram origin that have become part of the repertoire of Folk musicians. Some of these you make not know or be aware of their origin because you may have heard of them from white performers or other non-black americans. These songs range from sacred songs such as negro spirituals and black hymns to various secular types including, game, murder ballads, bad-man ballads, chain gang-prison songs, blues-ballads, banjo+fiddle etc..

.

.

.

Stagger Lee

other versions

.

.

.

Stagger Lee

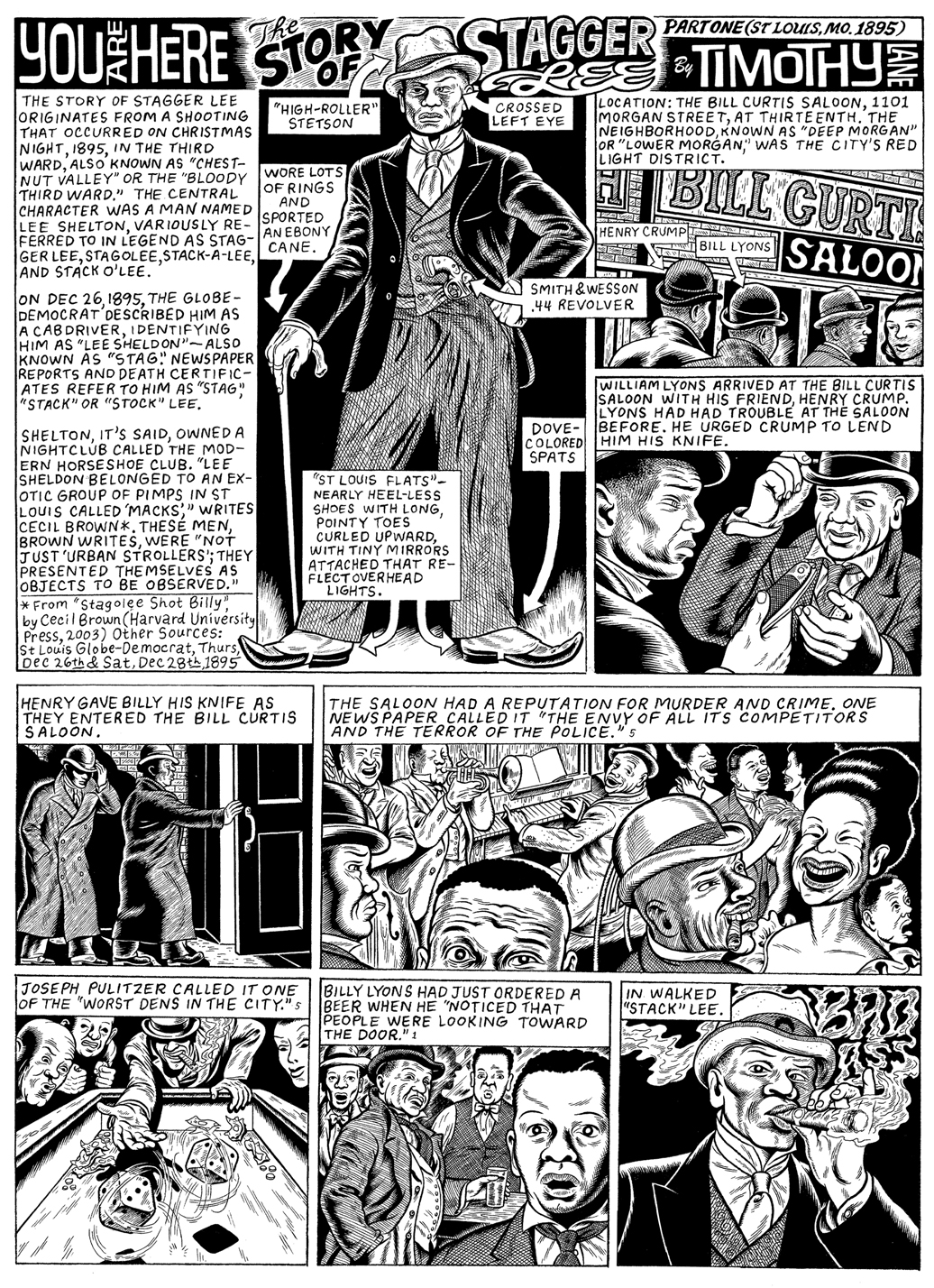

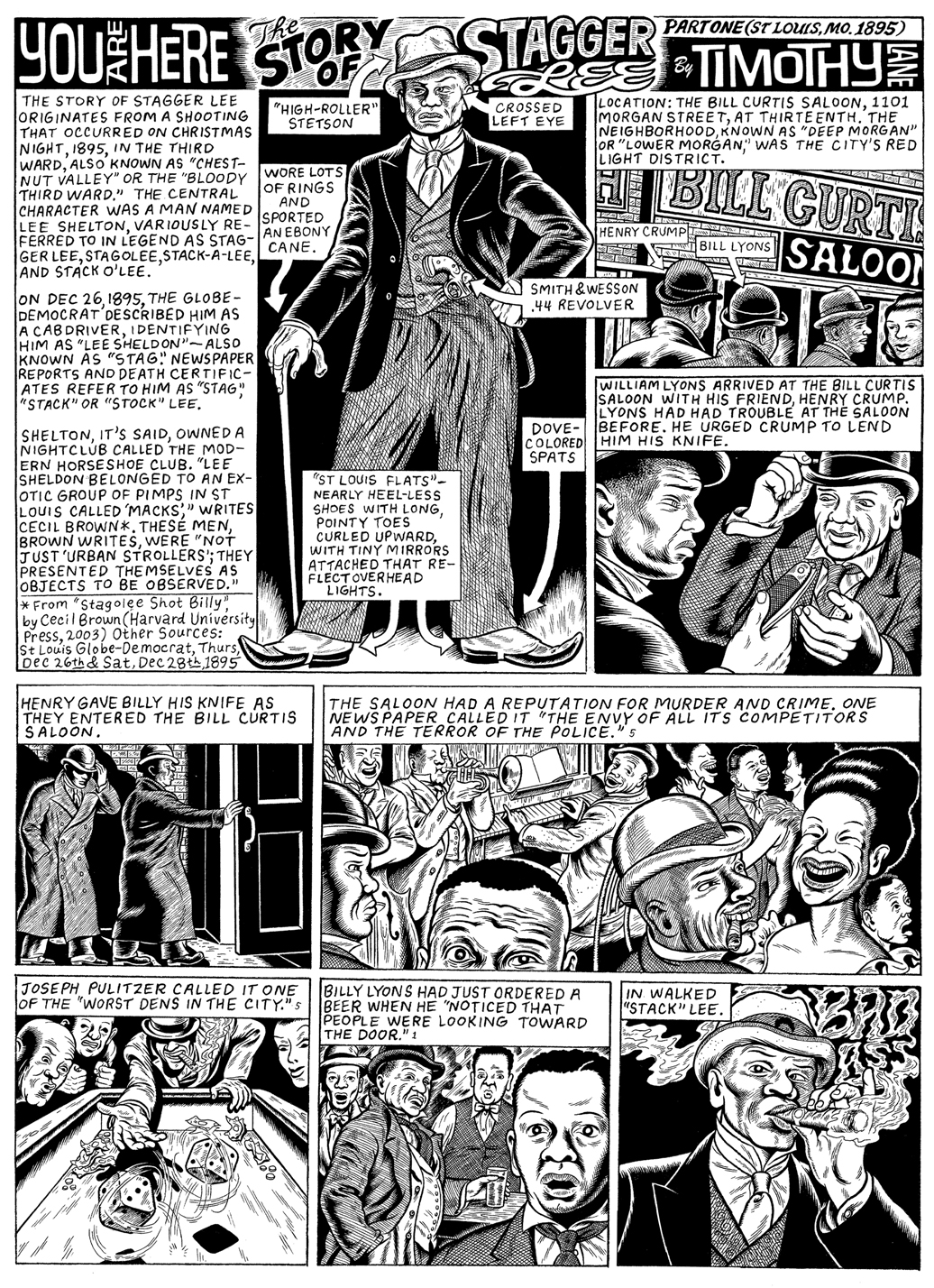

The historical "Stagger Lee" was Lee Shelton, an African-American pimp living in St. Louis, Missouri in the late 19th century. He was nicknamed "Stag Lee" or "Stack Lee", with a variety of explanations being given for the moniker: he was given the nickname because he 'went "stag"', meaning he was without friends; he took the nickname from a well-known riverboat captain called "Stack Lee"; or, according to John and Alan Lomax, he took the name from a riverboat owned by the Lee family of Memphis called the Stack Lee, which was known for its on-board prostitution.[2] He was well known locally as one of the "Macks", a group of pimps who demanded attention through their flashy clothing and appearance.[3] In addition to these activities, he was the captain of a black "Four Hundred Club", a social club with a dubious reputation.[4]

On Christmas night in 1895, Shelton and his acquaintance William "Billy" Lyons were drinking in the Bill Curtis Saloon. Lyons was also a member of St. Louis' underworld, and may have been a political and business rival to Shelton. Eventually, the two men got into a dispute, during which Lyons took Shelton's Stetson hat.[5] Subsequently, Shelton shot Lyons, recovered his hat, and left.[6] Lyons died of his injuries, and Shelton was charged, tried and convicted of the murder in 1897. He was pardoned in 1909, but returned to prison in 1911 for assault and robbery, and died in incarceration in 1912.[7]

The crime quickly entered into American folklore and became the subject of song as well as folktales and toasts. The song's title comes from Shelton's nickname, "Stag Lee" or "Stack Lee".[8] The name was quickly corrupted in the folk tradition; early versions were called "Stack-a-Lee" and "Stacker Lee"; "Stagolee" and "Stagger Lee" also became common. Other recorded variants include "Stackerlee", "Stack O'Lee", "Stackolee", "Stackalee", "Stagerlee", and "Stagalee".[9]

A song called "Stack-a-Lee" was first mentioned in 1897, in the Kansas City Leavenworth Herald, as being performed by "Prof. Charlie Lee, the piano thumper."[10] The earliest versions were likely field hollers and other work songs performed by African-American laborers, and were well known along the lower Mississippi River by 1910. That year, musicologist John Lomax received a partial transcription of the song,[11] and in 1911 two versions were published in the Journal of American Folklore by the sociologist and historian Howard W. Odum.[12]

The song was first recorded by Waring's Pennsylvanians in 1923, and became a hit. Another version was recorded later that year by Frank Westphal & His Regal Novelty Orchestra, and Herb Wiedoeft and his band recorded the song in 1924.[13] Also in 1924, the first version with lyrics was recorded, as "Skeeg-a-Lee Blues", by Lovie Austin. Ma Rainey recorded the song the following year, with Louis Armstrong on cornet, and a notable version was recorded by Frank Hutchison in 1927.[10]

Before World War II, it was commonly known as "Stack O'Lee". W.C. Handy wrote that this probably was a nickname for a tall person, comparing him to the tall smokestack of the large steamboat Robert E. Lee.[14] By the time W.C. Handy wrote that explanation in the 1920s, "Stack O' Lee" was already familiar in United States popular culture, with recordings of the song made by such pop singers of the day as Cliff Edwards.

The version by Mississippi John Hurt, recorded in 1928, is regarded as definitive.[10] In his version, as in all such pieces, there are many (sometimes anachronistic) variants on the lyrics. Several older versions give Billy's last name as "De Lyons" or "Deslile". Other notable pre-war versions were by Duke Ellington (1927), Cab Calloway (1931), and Woody Guthrie (1941).[10]

The Song and Myth of Stagger Lee

There is a song that has been recorded by James Brown, Nick Cave and Neil Diamond. The Clash, Pat Boone, Fats Domino and Bob Dylan. Duke Ellington, The Grateful Dead, Woody Guthrie, The Ventures, Ike & Tina Turner, Ma Rainey and Jerry Lee Lewis. Tom Jones did it. So did Beck, Mississippi John Hurt, the Black Keys and Elvis Presley.

Over 400 different artists have recorded this song since the first recording in 1923.

Margaret Walker and James Baldwin wrote poems from the song. It's been refashioned as a musical, two novels, a short story, an award-winning graphic novel, Ph.D. dissertations and, in 2008, a pornographic feature film.

The song has lived as Ragtime, a Broadway showtune, Blues, Jazz, Honky Tonk, Country, 50s Rock and Roll, Ska, Folk, Surf, 70s punk, Heavy Metal, 90s punk, Rap. Even Hawaiian. The song's character lives large in Gangsta Rap.

The song tells the story of a murder. On Christmas Eve, 1895, in a St. Louis saloon, "Stag" Lee Shelton, a black pimp, shot William "Billy" Lyons. Eyewitnesses say Billy snatched Stag's Stetson hat. Boom, boom, boom, boom went Stag's forty-four. You don't mess with a man's hat.

The events of that night were immediately cast into song. Like a game of Chinese Whispers it swept through the South, following railway lines and paddle steamers of the Mississippi. Told and retold. Sung and resung. Changing a little bit each time. Reality slipped away and the myth was created.

The legend of Stagger Lee is one of the most important and enduring stories from American folklore. It is a tale that originated from African-American oral tradition, and it also has become a very popular story within the white community.

There are many different versions of the tale, but here is the general storyline. Stagger Lee (also known as Stagolee, Stack O' Lee, Stackerlee, Stackalee etc.) gets into a dispute with a man named Billy DeLyon (also known as Billy the Lion or Billy Lyons) after losing his Stetson hat to Billy while gambling. Stagger Lee pulls a gun--sometimes identified as a .45, other times as a "smokeless .44"--on Billy who then pleads to be spared for the sake of his wife and children. Showing no compassion at all, Stagger Lee cold-bloodedly shoots and kills his opponent.

The killer's reputation for "badness" is a key to the story. According to some classic musical recordings of the legend (such as "Mississippi" John Hurt's "Stack O'Lee Blues"), the authorities are too frightened of Stagger Lee to arrest him for his crime. In some versions of the tale, he is eventually caught by the authorities, but the judge refuses to sentence him to prison because he fears that the badman will strike back against him. In certain tellings of the story, Stagger Lee appears in hell after he is killed or executed, but is so "bad" that he takes control of the devil's kingdom and turns it into his own badman's paradise.

“SHOT IN CURTIS'S PLACE

“William Lyons, 25, coloured, a levee hand, living at 1410 Morgan Street, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o'clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan streets, by Lee Sheldon, also coloured.

“Both parties, it seems, had been drinking, and were feeling in exuberant spirits. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. The discussion drifted to politics, and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon's hat from his head.

“The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen [...] When his victim fell to the floor, Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away.”

- St Louis Globe-Democrat, December 26, 1895.

other versions

More!

More!