Alabama says they are safe enough for KFC, but too dangerous for parole

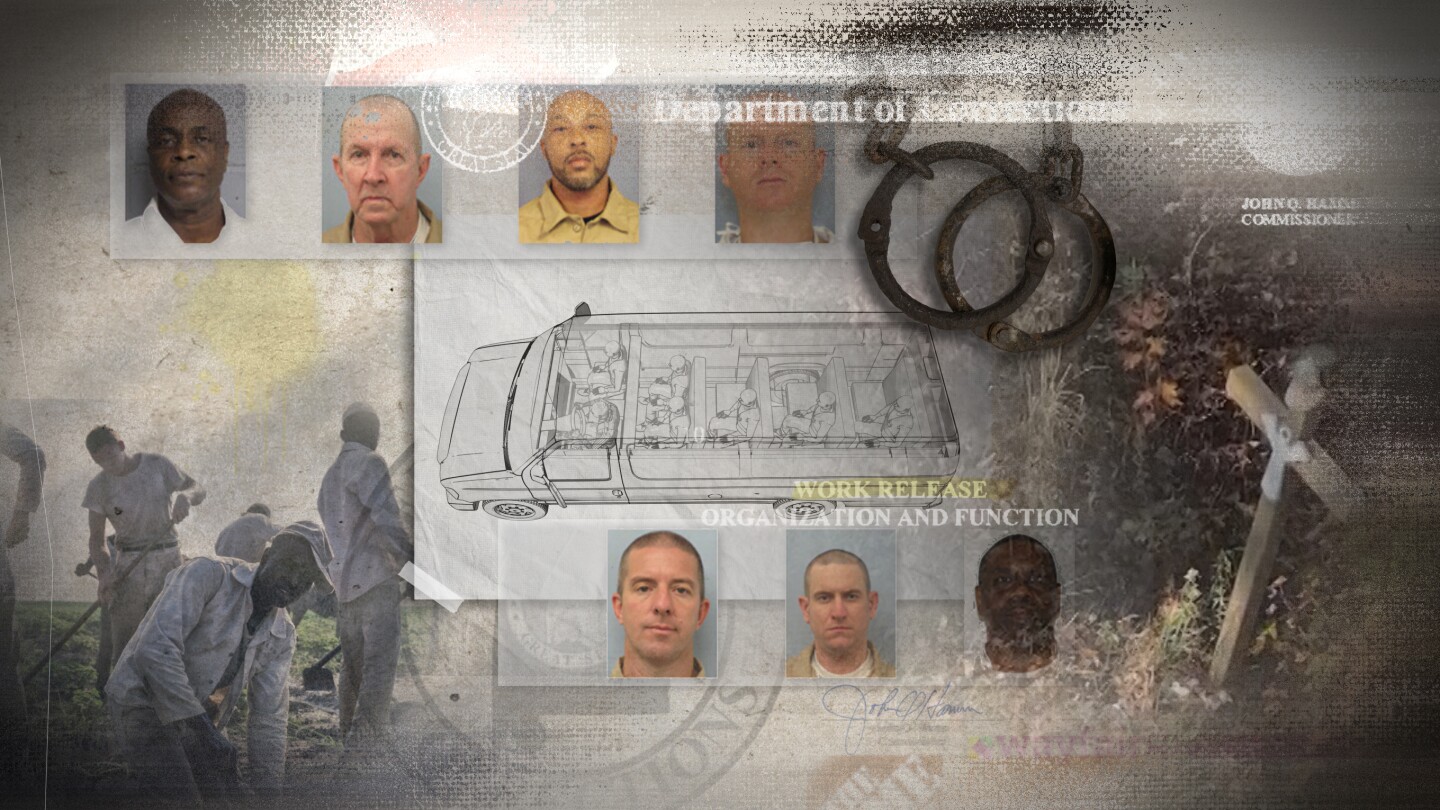

Inmates who are denied parole are going to work in a system that generates millions for the state each year, a system that’s been called a “modern-day form of slavery."

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

Alabama says they are safe enough for KFC, but too dangerous for parole

- Published: Dec. 10, 2024, 6:37 a.m.

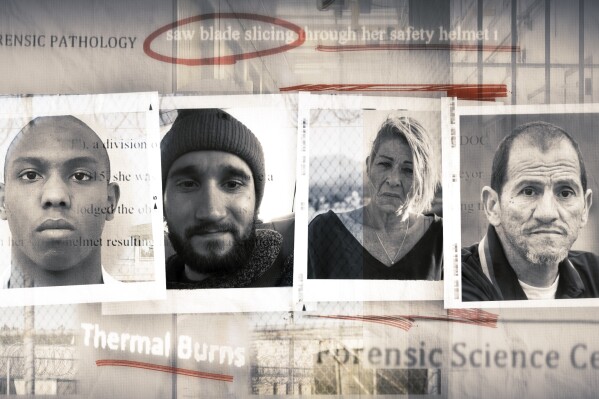

The face of Jerry Dino Helton at the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery, Alabama. He one of many who were denied of parole in Alabama. (Photo Illustration/Tamika Moore/AL.com) AL.com

By Ivana Hrynkiw | ihrynkiw@al.com

Editor's Note

Last year, Alabama’s top prosecutor said the parole system is working, and “dangerous offenders are largely the only ones left behind bars.” Was he right? Thousands of people in Alabama lockups are eligible for parole, and each year fewer and fewer are freed. In this series, Denied: Alabama's broken parole system, AL.com highlights several recent cases. You can decide if Attorney General Steve Marshall was right when he said "there is simply nobody else to 'reform.'"

Michael Campbell gets up with the sun and makes his way to a KFC in north Alabama under the familiar, bearded face of Colonel Sanders.

He dumps chicken in hot oil, filling striped buckets with thighs and drums.

At the end of his shift, he hangs up his apron and boards a bus. A bus headed back to prison.

The next morning, he gets back on the bus, puts on that KFC apron and starts all over again.

He is going to work as the state takes a chunk of each paycheck, raking in nearly $13 million last year in a system that’s being sued over claims of labor trafficking and operating a “modern-day form of slavery.”

Like more than a thousand other Alabama inmates, Campbell is on work release. That means he is deemed safe enough by the prison system to work in public, unsupervised and without any guardrails to protect the community.

But the entirely separate Alabama Parole Board decided last summer that Campbell, despite working in public each day, wasn’t safe enough to send home to sleep.

“It’s absurd,” said Will Tucker, the southern director for the nonprofit Jobs to Move America.

Alabama’s parole board frequently denies release to people who are in minimum-security facilities, working regular jobs and walking around in regular clothes or restaurant uniforms each day, arguing that while they’re safe to work, they’re not safe enough to sleep at home.

In fact, being on work release doesn’t seem to help their chances much at all. This year, according to August data from the prison system, just 151 people in prison work release and work centers were released on parole, despite already meeting the prisons’ standards for being allowed in public with minimal supervision. That’s compared to the 137 paroled from the highest-security facilities, and 135 from medium security.

Experts, lawyers and advocates say that doesn’t make sense.

“One would expect people on work release to be frequently granted parole because ADOC has already determined them to be safe working in the community,” said Jessica Vosburgh, an attorney for the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Vosburg represents several inmates who are suing Alabama in state court, arguing that the work release policies violate the state constitution’s ban on slavery and involuntary servitude.

In a separate lawsuit in federal court, 10 current and former Alabama inmates are arguing that the state systemically denies parole to people on work release because the state benefits by keeping a big piece of each paycheck. The federal suit calls the Alabama system labor trafficking and a “modern-day form of slavery.”

The Alabama Attorney General’s office is fighting back in both cases.

How work release works

Jerry Helton, a Navy veteran, is serving a life sentence for a series of charges stemming from writing bad checks in the 1990s. He’s been up for parole six times — without any luck.

“Working every day, making $300 a week, actually working a real job, wearing free world clothes and unsupervised out in the community, and they still deny you parole,” Helton told AL.com through the prison phone. “That doesn’t make any sense to me.”

There were about 3,200 inmates housed in minimum-security prison facilities across Alabama in August, according to prison records. That means they are cleared to work in the community without direct supervision.

But that status is decided by prison officials, influenced by a decent prison record, an inmate’s criminal past and other factors. And that decision has no clear effect on Alabama’s separate, three-member parole board.

These are some of the businesses in Alabama that employ inmates through work release programs and are being sued in federal court. Ramsey Archibald | rarchibald@al.com

The last two times Helton was denied — he recalled those hearings were in 2018 and 2021 — he was on work release in north Alabama. He first worked in a warehouse, sorting DVDs and CDs to sell to big box stores. Then, Helton moved to a higher-paying job driving heavy machinery at a lumberyard. He worked 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., unsupervised.

In August, there were 1,430 inmates like Helton in work release facilities, meaning they can work for private employers like McDonalds, Burger King, BamaBudweiser, car dealerships and lumberyards. Another 1,744 that month were at work centers, meaning they can be sent out to work for local governments, like the city of Montgomery or Jefferson County.

Both work facilities are suitable for people “who do not pose a significant risk to self or others” according to prison policies, and for those who are expected to soon “transition and reintegrate back into the community.”

Inmates on both status levels work without direct supervision, sometimes six days a week, and the prison bus that carts inmates to their jobs is even driven by a fellow inmate. Many in work release facilities are given “passes” for home visits, allowing them to leave prison and report back at the end of the weekend.

But between January and August of 2024, prison data shows that just 40 people were paroled from work centers, and just 111 from work release centers.

It comes even as paroles have increased under public scrutiny, after AL.com reporting showed that nearly no one was being paroled anymore. The parole rate rose from a historic low of 8% last year to 20% in 2024, according to parole board data.

The Birmingham Community Based Facility, a minimum-security work release facility run by the prison system. Photo by the Alabama Department of Corrections

“I can understand it if I’m behind the fence and I’ve committed a violent crime and I had a lot of disciplinaries for fighting and stuff like that,” Helton added. “But here I am at a work release going out every day unsupervised, working a job, making real money, coming back, and they still deny you parole.”

Helton described a few disciplinaries he received during those years, several for suboxone use and another for having a consensual relationship with a woman he worked with. But none were for violent offenses.

After Helton’s denial in 2021, he kept on working, hoping and praying that one day he would leave prison for good. But earlier this year, he had a heart attack. He was transferred to the high-security Kilby Correctional Facility for medical care that the minimum-security center couldn’t provide.

For months, Helton lived in the prison infirmary. There, Helton discovered he was littered with cancerous tumors, which had spread throughout his body. He described some as the size of a lemon; another an acorn, while a third was a BB. “They’re everywhere,” he said quietly.

But Helton’s story is not unusual in Alabama. The federal lawsuit dug into parole rates last summer, looking at the cases that were heard in public between June and August. The suit argues that the board granted parole to just 10 of the 74 people who were already safe enough for at work release. During that same period, 86.5% of inmates assigned to work release were denied.

Denied: Alabama's broken parole system

- Alabama lawmakers grill parole board over low parole rates: ‘We want specific answers’

- Alabama splits over whether to parole dying inmate the prison system already sent home

- Alabama prisons let out ‘old, sick and dying’ inmates denied parole

- Alabama lawmakers distance themselves from parole board, families say loved ones ‘stuck for life’

- Alabama argued to keep Lowe’s shoplifter in prison. Roy Moore came to his defense.

And the parole board’s own data shows that last year, they granted parole to only 8% of people who had a hearing and were deemed to be low risk using the parole board’s own assessment, similar to the one the prison used to place those people in the public to work. The board granted 11% of those deemed as a moderate risk, and 4% of those with a high risk.

As a veteran, Helton said, if he had been paroled he could have gone to the VA earlier and received treatment. “I could have caught this (cancer) before it spread like this,” he said.

Recently, Helton’s nonprofit attorneys asked for him to be released on medical furlough so he could spend what doctors believe to be his final months at home with his children and grandchildren.

The prison commissioner, John Hamm, approved the furlough in November. When Helton finally walks out of prison, he will have spent over 27 years behind bars.

“I’m not a saint,” Helton repeated during a second call from prison, after the time on his first call ran out. “But I’ve done right things in my life... I’ve never hurt anyone.”

The money

In fiscal year 2023, the Alabama prison system reported that it collected $12.9 million from work release alone. In 2024, that number was $12.2 million.

Inmates on work release must pay the prison system 40% of their gross earnings “to assist in defraying the cost of his/her incarceration,” according to prison rules.

And that’s not all. Inmates who get a paycheck have to pay outstanding payments for court costs, attorneys fees, restitution, or child support. Drug test fees come next, along with $5 daily round-trip transportation fees to get to work. There’s also a $15 monthly laundry fee. And some private employers charge for things like safety glasses or work shoes.