You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential Afro-Latino/ Caribbean Current Events

- Thread starter Poitier

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?The Law of Afro-descendants has been "at fault" since its creation

Published: July 2, 2018 | 17:41

8% of vacancies in the public sector should be occupied with people from this group. In 2017 it was only 2%. There are no planned sanctions.

Afro-Uruguayan organizations were not surprised by the data on state admissions in 2017 released by the National Civil Service Office (ONC) which reflected a presence of members of this group that is barely a quarter of what was stipulated by law. The fact that there are no sanctions for the government body that violates this norm is used as one of the factors that explain it. But they also point to the lack of interest and the overlapped racism they notice in society.

"Uruguay has been — in a Machiavellian manner — brilliant in the implementation of racism", said Néstor Silva, national director of Organizaciones Mundo Afro, to ECOS.

According to the ONC report released this Monday by La Diaria, in 2017, 361 Afro-descendants were admitted into state jobs. This is 2.06% of all public sector admissions. According to Law 19.122, the Law of Afro-descendants, in order to boost their participation in the educational and labor areas, the percentage should be 8%.

"Since this law's implementation some parties have been at fault. The employers are at fault and also, regardless of whether this law is an achievement, there is no sanction for the government bodies that do not comply with it. This must be solved", indicates Fabiana Míguez, member of the Coordination of Afro-descendants.

Silva and Míguez are part of the advisory board that monitors the compliance with this law approved in 2013.

"Also, there is no specific protocol or unified criteria among the different public bodies", says Míguez.

The only state agency that met the quota in 2017 was the Department Board of Cerro Largo, in which three Afro-descendants were admitted into last year; this was 25% of all occupied vacancies. In the Banco República state-owned bank the percentage was 7.69%, in the Ministry of Public Works and Transport it was 7.58%, in the Intendancy of Cerro Largo it was 7.48% and in the Presidency of the Republic it was 7.16%. Of all Afro-descendant admissions, 162 (slightly less than half) were into the Army. According to Míguez, the high presence of members of the collective in the subordinate personnel of the Armed Forces is not surprising either.

The Coordination member is not encouraged to affirm if there is disinterest or not in the compliance with the law. "I want to be optimistic: perhaps there is lack of information. And what there is is an overlapped racism, some people think that affirmative action for labor inclusion is not welcomed", she noted.

Néstor Silva, of Mundo Afro, is more emphatic. "There is a central reason why this is not being fulfilled and it is the current structural racism. There are very deep cultural issues that are not going to be fixed in a short period of time regardless of legislation". He said that in Uruguay "it is a custom that some people cannot be in certain places". One example is "a black man handling customers in a bank".

Among the numbers that show the reality of this group, which is believed to represent 8.1% of the population, it is indicated that more than half (51.3%) have at least one unfulfilled basic need, 40% is poor and three out of every four young people do not finish high school.

For Silva, in some places there is no interest in complying with this law. For example, she pointed out that the law states that a commission shall be created in the Executive Power to monitor compliance, integrated with a representative of the Ministries of Social Development (Mides), Education and Culture (MEC) and Labor and Social Security (MTSS). The director of Mundo Afro has no complaints to make about Mides and MEC. "But if you ask me about Ministry of Labor, you will notice that it is missing, it is not there". At the same time, he indicates that, at the directorial level, the affirmations and intentions can point towards inclusion. "The managers, the mid-level managers do not comply".

According to La Diaria, since the implementation of this law, 1,117 Afro-descendants took up state jobs.

The Law of Afro-descendants has been "at fault" since its creation

Published: July 2, 2018 | 17:41

8% of vacancies in the public sector should be occupied with people from this group. In 2017 it was only 2%. There are no planned sanctions.

Afro-Uruguayan organizations were not surprised by the data on state admissions in 2017 released by the National Civil Service Office (ONC) which reflected a presence of members of this group that is barely a quarter of what was stipulated by law. The fact that there are no sanctions for the government body that violates this norm is used as one of the factors that explain it. But they also point to the lack of interest and the overlapped racism they notice in society.

"Uruguay has been — in a Machiavellian manner — brilliant in the implementation of racism", said Néstor Silva, national director of Organizaciones Mundo Afro, to ECOS.

According to the ONC report released this Monday by La Diaria, in 2017, 361 Afro-descendants were admitted into state jobs. This is 2.06% of all public sector admissions. According to Law 19.122, the Law of Afro-descendants, in order to boost their participation in the educational and labor areas, the percentage should be 8%.

"Since this law's implementation some parties have been at fault. The employers are at fault and also, regardless of whether this law is an achievement, there is no sanction for the government bodies that do not comply with it. This must be solved", indicates Fabiana Míguez, member of the Coordination of Afro-descendants.

Silva and Míguez are part of the advisory board that monitors the compliance with this law approved in 2013.

"Also, there is no specific protocol or unified criteria among the different public bodies", says Míguez.

The only state agency that met the quota in 2017 was the Department Board of Cerro Largo, in which three Afro-descendants were admitted into last year; this was 25% of all occupied vacancies. In the Banco República state-owned bank the percentage was 7.69%, in the Ministry of Public Works and Transport it was 7.58%, in the Intendancy of Cerro Largo it was 7.48% and in the Presidency of the Republic it was 7.16%. Of all Afro-descendant admissions, 162 (slightly less than half) were into the Army. According to Míguez, the high presence of members of the collective in the subordinate personnel of the Armed Forces is not surprising either.

The Coordination member is not encouraged to affirm if there is disinterest or not in the compliance with the law. "I want to be optimistic: perhaps there is lack of information. And what there is is an overlapped racism, some people think that affirmative action for labor inclusion is not welcomed", she noted.

Néstor Silva, of Mundo Afro, is more emphatic. "There is a central reason why this is not being fulfilled and it is the current structural racism. There are very deep cultural issues that are not going to be fixed in a short period of time regardless of legislation". He said that in Uruguay "it is a custom that some people cannot be in certain places". One example is "a black man handling customers in a bank".

Among the numbers that show the reality of this group, which is believed to represent 8.1% of the population, it is indicated that more than half (51.3%) have at least one unfulfilled basic need, 40% is poor and three out of every four young people do not finish high school.

For Silva, in some places there is no interest in complying with this law. For example, she pointed out that the law states that a commission shall be created in the Executive Power to monitor compliance, integrated with a representative of the Ministries of Social Development (Mides), Education and Culture (MEC) and Labor and Social Security (MTSS). The director of Mundo Afro has no complaints to make about Mides and MEC. "But if you ask me about Ministry of Labor, you will notice that it is missing, it is not there". At the same time, he indicates that, at the directorial level, the affirmations and intentions can point towards inclusion. "The managers, the mid-level managers do not comply".

According to La Diaria, since the implementation of this law, 1,117 Afro-descendants took up state jobs.

The Law of Afro-descendants has been "at fault" since its creation

Pending policies for dignification of the Afro-Mexican population

by BLANCA ESTELA BOTELLO | 07/03/2018 - 00:24:13

Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of Conapred, spoke about the pending policies in favor of this sector of Mexican society

cronica.com.mx

In Mexico, there are 1,4 million Afro-descendants, who in three years went from being invisible to having recognition as a sector of the country's population, noted Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (Conapred).

In an interview with Crónica, Haas Paciuc said that with the 2015 Intercensus Estimate there was a recognition of the Afro-Mexican population in the country, which is mainly concentrated in Guerrero and Oaxaca, although they are also in Coahuila.

"For Mexico it was a very important transformation, because we went from having the Afro-descendant population absolutely invisible to suddenly having knowledge of their lives in various parts of the country.

It is not a small population; they are really almost a million and a half, it is a much larger size than what we previously thought", she said.

This population, according to the head of Conapred, faces inequality gaps, where the illiteracy rate is higher than the non-black population's.

There is also a higher percentage of Afro-Mexicans in the Seguro Popular public health insurance program compared to the rest of the population, because they do not have access to another health service.

"We noticed that in certain communities where there is a high representation of Afro-descendant people, there is an inequality gap with other communities", said the human rights lawyer.

The indigenous and Afro-Mexican populations, she said, face similar conditions, "with an aggravating circumstance for Afro-Mexicans, which is invisibility".

Two pending issues with the Afro-descendant population, said Haas Paciuc, are their constitutional recognition as a part of society's pluri-ethnic diversity, as well as incorporating Afro-Mexican identity into the educational policy, that is, including it in textbooks and curricula.

She regretted that although there have been initiatives in the Congress of the Union to officialize the constitutional recognition of Afro-Mexicans, no progress on the subject has been made.

The new Legislature, which takes office in September, could be a good opportunity to advance the issue, and "without a doubt it will be part of the agenda that we are going to take to the new legislators."

She stressed that the contribution of Afro-Mexicans to the history of Mexico must be recognized, but also their current conditions require specific attention.

"It is nothing more than a matter of historical recognition, which is very important, but also realizing that they have specific problems hence the need to develop institutions and specific public policies to address their needs", said the former consultant of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Being present in Mexico since the colonial period, not all Afro-descendants identify as indigenous, although 60 percent of Afro-Mexicans are also indigenous, she said.

"There is a very distinct Afro-Mexican identity, which is recognized by the constitutions of Guerrero and Oaxaca as a Mexican root of Mexico's ethnic diversity and cannot be subsumed in a generic way under indigenous ethnic groups; they have a distinct identity.

What has happened in Mexico is that over time we have understood our country as one that is basically mestizo, and with this comes the idea that there are no diverse identities, and the truth is that this has invisibilized the specific situation of certain groups", said the Professor of Law graduated from New York University.

She emphasized that the recognition of diversity should not mean a division in racist terms.

"On the contrary, it is the recognition that there is diversity in Mexico, and that diversity deserves specific attention, especially when there are gaps in access to rights, as is the case of Afro-Mexicans, because at the same time we have to live in a country where ethnic and cultural diversity should not mean a difference in access to rights", she said.

She considers that Mexico, compared to other countries, is late to the agenda of recognition of people of African descent.

"In other countries, Afro-descendants have long had specific institutions. This is the case of Colombia, which has not only worked to recognize the historical legacy of these groups, but also for the advancement of their rights and their political articulation", said the president of Conapred.

Pending policies for dignification of the Afro-Mexican population

by BLANCA ESTELA BOTELLO | 07/03/2018 - 00:24:13

Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of Conapred, spoke about the pending policies in favor of this sector of Mexican society

cronica.com.mx

In Mexico, there are 1,4 million Afro-descendants, who in three years went from being invisible to having recognition as a sector of the country's population, noted Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (Conapred).

In an interview with Crónica, Haas Paciuc said that with the 2015 Intercensus Estimate there was a recognition of the Afro-Mexican population in the country, which is mainly concentrated in Guerrero and Oaxaca, although they are also in Coahuila.

"For Mexico it was a very important transformation, because we went from having the Afro-descendant population absolutely invisible to suddenly having knowledge of their lives in various parts of the country.

It is not a small population; they are really almost a million and a half, it is a much larger size than what we previously thought", she said.

This population, according to the head of Conapred, faces inequality gaps, where the illiteracy rate is higher than the non-black population's.

There is also a higher percentage of Afro-Mexicans in the Seguro Popular public health insurance program compared to the rest of the population, because they do not have access to another health service.

"We noticed that in certain communities where there is a high representation of Afro-descendant people, there is an inequality gap with other communities", said the human rights lawyer.

The indigenous and Afro-Mexican populations, she said, face similar conditions, "with an aggravating circumstance for Afro-Mexicans, which is invisibility".

Two pending issues with the Afro-descendant population, said Haas Paciuc, are their constitutional recognition as a part of society's pluri-ethnic diversity, as well as incorporating Afro-Mexican identity into the educational policy, that is, including it in textbooks and curricula.

She regretted that although there have been initiatives in the Congress of the Union to officialize the constitutional recognition of Afro-Mexicans, no progress on the subject has been made.

The new Legislature, which takes office in September, could be a good opportunity to advance the issue, and "without a doubt it will be part of the agenda that we are going to take to the new legislators."

She stressed that the contribution of Afro-Mexicans to the history of Mexico must be recognized, but also their current conditions require specific attention.

"It is nothing more than a matter of historical recognition, which is very important, but also realizing that they have specific problems hence the need to develop institutions and specific public policies to address their needs", said the former consultant of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Being present in Mexico since the colonial period, not all Afro-descendants identify as indigenous, although 60 percent of Afro-Mexicans are also indigenous, she said.

"There is a very distinct Afro-Mexican identity, which is recognized by the constitutions of Guerrero and Oaxaca as a Mexican root of Mexico's ethnic diversity and cannot be subsumed in a generic way under indigenous ethnic groups; they have a distinct identity.

What has happened in Mexico is that over time we have understood our country as one that is basically mestizo, and with this comes the idea that there are no diverse identities, and the truth is that this has invisibilized the specific situation of certain groups", said the Professor of Law graduated from New York University.

She emphasized that the recognition of diversity should not mean a division in racist terms.

"On the contrary, it is the recognition that there is diversity in Mexico, and that diversity deserves specific attention, especially when there are gaps in access to rights, as is the case of Afro-Mexicans, because at the same time we have to live in a country where ethnic and cultural diversity should not mean a difference in access to rights", she said.

She considers that Mexico, compared to other countries, is late to the agenda of recognition of people of African descent.

"In other countries, Afro-descendants have long had specific institutions. This is the case of Colombia, which has not only worked to recognize the historical legacy of these groups, but also for the advancement of their rights and their political articulation", said the president of Conapred.

Pending policies for dignification of the Afro-Mexican population

Pending policies for dignification of the Afro-Mexican population

by BLANCA ESTELA BOTELLO | 07/03/2018 - 00:24:13

Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of Conapred, spoke about the pending policies in favor of this sector of Mexican society

cronica.com.mx

In Mexico, there are 1,4 million Afro-descendants, who in three years went from being invisible to having recognition as a sector of the country's population, noted Alexandra Haas Paciuc, president of the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (Conapred).

In an interview with Crónica, Haas Paciuc said that with the 2015 Intercensus Estimate there was a recognition of the Afro-Mexican population in the country, which is mainly concentrated in Guerrero and Oaxaca, although they are also in Coahuila.

"For Mexico it was a very important transformation, because we went from having the Afro-descendant population absolutely invisible to suddenly having knowledge of their lives in various parts of the country.

It is not a small population; they are really almost a million and a half, it is a much larger size than what we previously thought", she said.

This population, according to the head of Conapred, faces inequality gaps, where the illiteracy rate is higher than the non-black population's.

There is also a higher percentage of Afro-Mexicans in the Seguro Popular public health insurance program compared to the rest of the population, because they do not have access to another health service.

"We noticed that in certain communities where there is a high representation of Afro-descendant people, there is an inequality gap with other communities", said the human rights lawyer.

The indigenous and Afro-Mexican populations, she said, face similar conditions, "with an aggravating circumstance for Afro-Mexicans, which is invisibility".

Two pending issues with the Afro-descendant population, said Haas Paciuc, are their constitutional recognition as a part of society's pluri-ethnic diversity, as well as incorporating Afro-Mexican identity into the educational policy, that is, including it in textbooks and curricula.

She regretted that although there have been initiatives in the Congress of the Union to officialize the constitutional recognition of Afro-Mexicans, no progress on the subject has been made.

The new Legislature, which takes office in September, could be a good opportunity to advance the issue, and "without a doubt it will be part of the agenda that we are going to take to the new legislators."

She stressed that the contribution of Afro-Mexicans to the history of Mexico must be recognized, but also their current conditions require specific attention.

"It is nothing more than a matter of historical recognition, which is very important, but also realizing that they have specific problems hence the need to develop institutions and specific public policies to address their needs", said the former consultant of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Being present in Mexico since the colonial period, not all Afro-descendants identify as indigenous, although 60 percent of Afro-Mexicans are also indigenous, she said.

"There is a very distinct Afro-Mexican identity, which is recognized by the constitutions of Guerrero and Oaxaca as a Mexican root of Mexico's ethnic diversity and cannot be subsumed in a generic way under indigenous ethnic groups; they have a distinct identity.

What has happened in Mexico is that over time we have understood our country as one that is basically mestizo, and with this comes the idea that there are no diverse identities, and the truth is that this has invisibilized the specific situation of certain groups", said the Professor of Law graduated from New York University.

She emphasized that the recognition of diversity should not mean a division in racist terms.

"On the contrary, it is the recognition that there is diversity in Mexico, and that diversity deserves specific attention, especially when there are gaps in access to rights, as is the case of Afro-Mexicans, because at the same time we have to live in a country where ethnic and cultural diversity should not mean a difference in access to rights", she said.

She considers that Mexico, compared to other countries, is late to the agenda of recognition of people of African descent.

"In other countries, Afro-descendants have long had specific institutions. This is the case of Colombia, which has not only worked to recognize the historical legacy of these groups, but also for the advancement of their rights and their political articulation", said the president of Conapred.

Pending policies for dignification of the Afro-Mexican population

The story of the quilombo that helped to build Brasília — and fears losing land to luxury condominiums

João Fellet | 07/01/2018

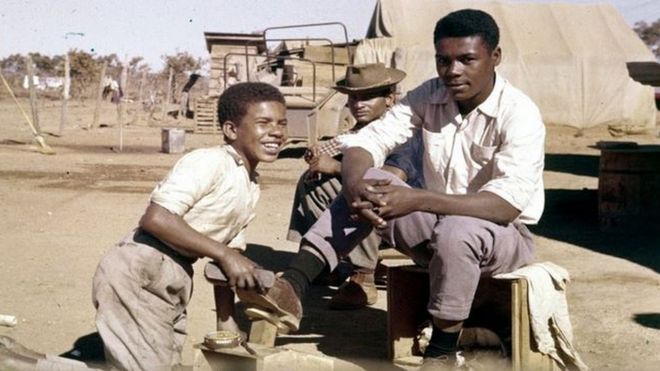

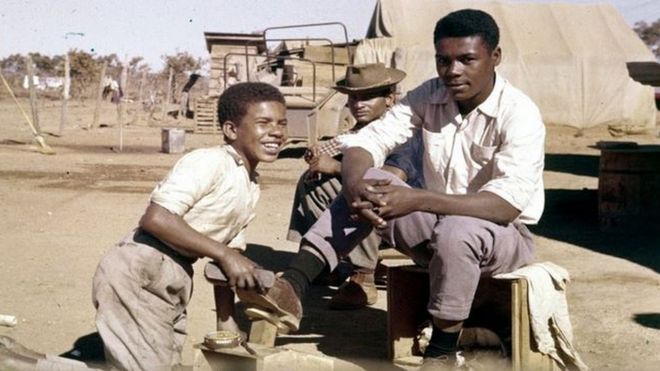

Workers in Cidade Livre (present-day Núcleo Bandeirante), the working-class neighborhood that built Brasília, in 1959. PUBLIC ARCHIVE OF THE FEDERAL DISTRICT

Before hosting the most important buildings in Brasília, Esplanada dos Ministérios was an open field where descendants of slaves used to graze cattle.

They were residents of Quilombo Mesquita, installed in the region since the 18th century and played an important — and little known — role in the city's founding.

272 years after its founding, the quilombo is now threatened by the capital's expansion and the accelerated land valorization in the region — the target of a real estate company that has former president José Sarney as one of its partners.

"Quilombolas had a direct participation in the city's construction, but, unfortunately, they are rarely portrayed as main characters in its history", says researcher Manoel Barbosa Neves, author of the book Quilombo Mesquita - História, Cultura e Resistência and resident of the community, on the border of the Federal District with Goiás.

He says quilombolas helped erect the canteens, lodgings and dining rooms that received the first waves of candangos, as the migrant workers who got Brasília off the drawing board became known.

Everyday, they filled wagons and ox carts with fruits, vegetables, meat, milk and sweets produced in the community and transported them to the construction sites, when food production in Brasília was nil.

Catetinho

Older residents say that, even before the arrival of the candangos, eight residents of Mesquita helped build Catetinho, the residence designed by Oscar Niemeyer so that the then president Juscelino Kubitschek could follow the works of the capital from the beginning, in 1956. And women from the community worked as cooks in Catetinho.

According to the quilombo's Technical Report of Land Identification and Demarcation, published in 2011 by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra), residents of Mesquita also helped build in 1958 the Saia Velha plant, the first hydroelectric power plant to serve the capital.

Sinfrônio Lisboa da Costa, a carpenter that worked on Catetinho and died at 90 years old in 2015, used to say he let Kubitschek in his house several times and helped him identify strategic points for the capital's construction.

Honored by the Federal District's government in 2012, he lamented in the ceremony that other quilombolas who accompained him in the works had already died. "They also had to be recognized, but they could not wait", he said.

Gold rush

The origins of Quilombo Mesquita go back to the gold rush in the 18th century. The rush led to the creation of several villages in the interior of Goiás — one of them being Santa Luzia, founded in 1746 by São Paulo bandeirante Antônio Bueno de Azevedo. Enslaved black people made up the majority of the population in the region.

It is said in the quilombo that, as mining declined, Portuguese captain Paulo Mesquita decided to leave Santa Luzia and left a farm for three freed slave women.

Manoel Neres says that, in time, others joined the community headed by women — many of them slaves in search of refuge who, in order to get there, traveled cattle trails that linked Goiás to Salvador and Rio de Janeiro.

Marriages between pioneer residents and those who came later gave birth to four family trees. These four trunks cover almost all of the nearly 1,200 families who now live in Mesquita, according to Neres.

Religious festivals such as Folia de Reis and Festa do Divino Espírito Santo are the main events in Mesquita's calendar. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

The construction of Brasília

Until the construction of Brasília, the community lived relatively isolated from the outside world. Most of the families were engaged in agriculture, cattle raising and the production of quince cheese, marketed in Luziânia, the city built on where Santa Luzia used to be.

With the capital's inauguration in 1960, their routine began to change.

Manoel Neres says that, on one hand, the residents "began to have access to elements of modern life, such as electricity and telephones". The capital's transfer facilitated the sale of food grown and created jobs for many quilombolas.

On the other hand, the village started dealing with previously non-existent problems, such as armed violence and drug trafficking. And they began to lose land.

One resident interviewed during the elaboration of the Incra report said quilombolas abandoned areas in Santa Maria, in the present-day Federal District, "fearing the city that was arriving there".

"Our house was near the Navy, but that was government land, so we had to move", said another resident.

According to Manoel Neres, the movement of airplanes and military on the eve of construction made the community relive a trauma from the time of World War II (1939–1945) when residents were forcibly recruited for combat.

"Many ended up leaving places close to the capital and retreating back into the core of Mesquita", says the researcher.

Others were expelled for failing to prove ownership of land destined for the construction of satellite towns. "The quilombola territory was disregarded in the Federal District's demarcation process", states the Incra report.

After the capital's construction, community land began to be coveted by outsiders.

"There was a lot of harassment for the sale of properties. Due to necessity, many villagers ended up disposing of them for ridiculous prices. They sold their land in order to buy medicine and clothes", says Neres.

Often land purchased from the quilombolas was soon resold. One of these transactions brought to the territory Maranhão politician José Sarney.

According to Incra's report, Sarney bought in the 1980's two land lots that had been expropriated from the community in the past. One of them gave rise to the Pecurimã farm he visited during the weekends while he was president.

In 2004, he sold the properties to Divitex Pericumã Empreendimentos Imobiliários, the real estate company of which he became a shareholder. Another partner of the company is attorney Antônio Carlos de Almeida Castro, known as Kakay, whose clients include several illustrious politicians in Brasília.

The periphery comes to Mesquita

In 1990, urbanization in the region increased with the creation of the Cidade Oriental municipality, a subdivision of Luziânia that received a habitation nucleus.

At one point quince cheese production was one of the main sources of income for Quilombo Mesquita. ANA CAROLINA A. FERNANDES

With the expansion of urban space, one housing project for low-income families — Jardim Edite — was built within the area originally claimed by the quilombo. In 2011, Incra excluded the public housing project from the territory in process of demarcation.

There are still several small farms within the territory claimed by the community. According to Incra, about 100 non-quilombola families lived in the area in 2011. Residents say the number is much higher now.

Demarcation

After the Constitution of 1988 determined the demarcation of quilombos, several communities mobilized to obtain land titles.

In Mesquita, the first step occured in 2006, when Fundação Cultural Palmares (the government body designed for promotion and preservation of Afro-Brazilian art and culture under the Ministry of Culture) recognized it as a remaining quilombo community.

Five years later, Incra published the community's Technical Report of Land Identification and Demarcation, defining its extension as 4300 hectares — the equivalent to 4000 football fields. According to Incra, the land claimed "represents only a fraction of the community's ancestral lands" and was delimited in order to guarantee the group's physical, social and cultural reproduction.

Then began the stage — which is not yet overcome — where non-quilombola residents and others interested in the territory can contest the report.

In order for the demarcation to be completed, the Presidency of the Republic must expropriate real estate within the territory and indemnify the owners. Only then can Incra give the community the collective and imprescriptible land title.

Sandra Braga says quilombolas still have not been recognized for their role in Brasília's founding. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

Of the approximately 3200 quilombos already recognized in Brazil, just over 200 have received land titles. Like in Mesquita's case, several processes are held back by impasses regarding expropriation and indemnification of non-quilombolas.

Reduction of the quilombo

The demarcation of the quilombo had an unfolding at the end of May, when Incra's Board of Directors issued a resolution authorizing the president of the government body to reduce the size of the territory to 971 hectares, 22% of the area originally planned.

The announcement was harshly criticized by quilombola associations. According to the National Coordination of Articulation of Black Rural Quilombola Communities (Conaq), the manoeuvre set a precedent for the reduction of other quilombos.

The resolution was also condemned by the Public Prosecutor's Office (MPF), which recomended its repeal. According to the government body, the decision "completely disregarded" studies conducted by Incra itself during the identification of the quilombo.

The oldest house in Quilombo Mesquita; with Brasília's founding, the value of land in the region has gone up. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

Last week, Incra announced that it would abide by MPF's suggestion and revoke the resolution while it rediscussed the case.

In a statement to BBC News Brasil, Incra said the reduction had been proposed by Quilombo Mesquita Renewal Association, a community organization of the quilombolas.

President of the association, Valcinei Batista Silva says the reduction would unlock the demarcation process and it is supported by the majority of the residents.

According to him, Incra's first intention to reserve 4300 hectares for the community proved to be unfeasible, since the government does not have the resources to expropriate all the non-quilombolas that live in the area.

Silva states that, should the proposed reduction be applied, the quilombolas would maintain all the territories they occupy now. "It is a proposal that allows Incra to work, send resources for expropriation and nobody would have to leave the land they're currently in."

Former president of the association, Sandra Pereira Braga says the current management's proposal does not have the support of the community and was articulated "in collusion with companies, farmers and speculators" interested in the territory.

"I have no doubt that there are powerful interests behind this", she says. "Most people in the community are totally against the reduction of territory — this is what Incra would find out had it consulted us before making any decisions."

Braga mentions, among those who would benefit from the reduction, Divitex Pecurimã — a company that has Sarney and Kakay as shareholders and would be, according to her, interested in building luxury condominiums in the territory.

With the growth of Brasília, a lot of areas around the capital began to host high-end housing complexes. At 40 km from the center of Brasília and near a highway that gives access to the city, the quilombo region would have huge potential for such enterprises, says Braga.

One of Sarney's press officers said the former president would not speak on the case. Kakay said he has never been to the region and does not follow the real estate company's administration, only acting as a "silent partner".

In a statement to BBC News Brasil, Divitex Pericumã Empreendimentos Imobiliários' attorney, Orlando Diniz Pinheiro, said that the company bought land in the region two years before the regularization of the quilombo began, and therefore "was not aware of the dispute (in relation to the territory)".

According to Pinheiro, quilombolas never inhabited the areas belonging to Divitex Pericumã. He says the company questions in court the land's inclusion in the area defined by Incra as the ancestral territory of the community.

The attorney says the land in process of demarcation "far exceeds the actual area where the Mesquita community resides". He says, however, that the company never exerted any pressure on government bodies for the quilombo to be reduced.

Pinheiro says the land possessed by the company is being leased for grain farming, but nothing prevents it from harboring real estate investments in the future — the activity mentioned in the company's corporate purpose.

"The families that are seeking demarcation have all purchased land in the region, they are not landowners in the quilombola area", states the attorney.

Quilombola Sandra Pereira Braga disputes the statement and says her ancestors have lived in the region for almost 300 years.

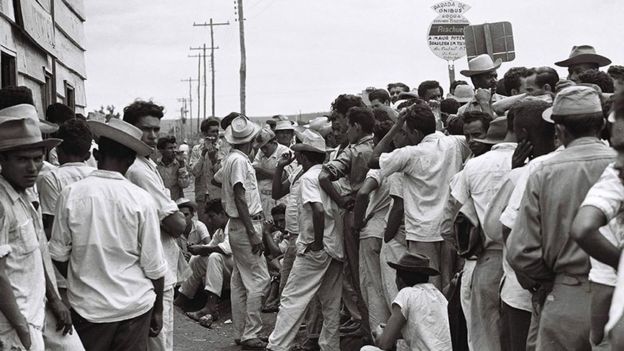

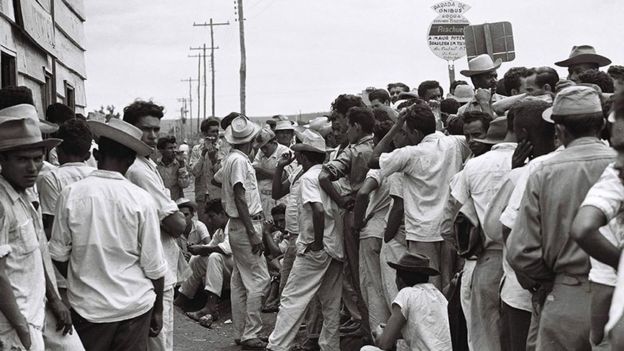

A line of candangos, the migrant workers that helped erect Brasília; city was built in less than four years. PUBLIC ARCHIVE OF THE FEDERAL DISTRICT

She says the quilombo celebrated the announcement that Incra would repeal the proposal to reduce the territory while the case was rediscussed, but the community will continue to mobilize until the withdrawal is definitive.

Braga says that, 58 years after Brasília's founding, the quilombo still fights for the recognition of its role in the construction of the city and, most importantly, for it to simply continue existing in the outskirts of the capital.

"If it wasn't for Mesquita, Brasília would not exist", she says.

The story of the quilombo that helped to build Brasília — and fears losing land to luxury condominiums

João Fellet | 07/01/2018

Workers in Cidade Livre (present-day Núcleo Bandeirante), the working-class neighborhood that built Brasília, in 1959. PUBLIC ARCHIVE OF THE FEDERAL DISTRICT

Before hosting the most important buildings in Brasília, Esplanada dos Ministérios was an open field where descendants of slaves used to graze cattle.

They were residents of Quilombo Mesquita, installed in the region since the 18th century and played an important — and little known — role in the city's founding.

272 years after its founding, the quilombo is now threatened by the capital's expansion and the accelerated land valorization in the region — the target of a real estate company that has former president José Sarney as one of its partners.

- Abolition of slavery in 1888 was voted by the elite to avoid land reform, says historian

- Beyond Princess Isabel, 6 Brazilians who fought to end slavery

"Quilombolas had a direct participation in the city's construction, but, unfortunately, they are rarely portrayed as main characters in its history", says researcher Manoel Barbosa Neves, author of the book Quilombo Mesquita - História, Cultura e Resistência and resident of the community, on the border of the Federal District with Goiás.

He says quilombolas helped erect the canteens, lodgings and dining rooms that received the first waves of candangos, as the migrant workers who got Brasília off the drawing board became known.

Everyday, they filled wagons and ox carts with fruits, vegetables, meat, milk and sweets produced in the community and transported them to the construction sites, when food production in Brasília was nil.

Catetinho

Older residents say that, even before the arrival of the candangos, eight residents of Mesquita helped build Catetinho, the residence designed by Oscar Niemeyer so that the then president Juscelino Kubitschek could follow the works of the capital from the beginning, in 1956. And women from the community worked as cooks in Catetinho.

According to the quilombo's Technical Report of Land Identification and Demarcation, published in 2011 by the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra), residents of Mesquita also helped build in 1958 the Saia Velha plant, the first hydroelectric power plant to serve the capital.

Sinfrônio Lisboa da Costa, a carpenter that worked on Catetinho and died at 90 years old in 2015, used to say he let Kubitschek in his house several times and helped him identify strategic points for the capital's construction.

Honored by the Federal District's government in 2012, he lamented in the ceremony that other quilombolas who accompained him in the works had already died. "They also had to be recognized, but they could not wait", he said.

Gold rush

The origins of Quilombo Mesquita go back to the gold rush in the 18th century. The rush led to the creation of several villages in the interior of Goiás — one of them being Santa Luzia, founded in 1746 by São Paulo bandeirante Antônio Bueno de Azevedo. Enslaved black people made up the majority of the population in the region.

It is said in the quilombo that, as mining declined, Portuguese captain Paulo Mesquita decided to leave Santa Luzia and left a farm for three freed slave women.

Manoel Neres says that, in time, others joined the community headed by women — many of them slaves in search of refuge who, in order to get there, traveled cattle trails that linked Goiás to Salvador and Rio de Janeiro.

Marriages between pioneer residents and those who came later gave birth to four family trees. These four trunks cover almost all of the nearly 1,200 families who now live in Mesquita, according to Neres.

Religious festivals such as Folia de Reis and Festa do Divino Espírito Santo are the main events in Mesquita's calendar. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

The construction of Brasília

Until the construction of Brasília, the community lived relatively isolated from the outside world. Most of the families were engaged in agriculture, cattle raising and the production of quince cheese, marketed in Luziânia, the city built on where Santa Luzia used to be.

With the capital's inauguration in 1960, their routine began to change.

Manoel Neres says that, on one hand, the residents "began to have access to elements of modern life, such as electricity and telephones". The capital's transfer facilitated the sale of food grown and created jobs for many quilombolas.

On the other hand, the village started dealing with previously non-existent problems, such as armed violence and drug trafficking. And they began to lose land.

One resident interviewed during the elaboration of the Incra report said quilombolas abandoned areas in Santa Maria, in the present-day Federal District, "fearing the city that was arriving there".

"Our house was near the Navy, but that was government land, so we had to move", said another resident.

According to Manoel Neres, the movement of airplanes and military on the eve of construction made the community relive a trauma from the time of World War II (1939–1945) when residents were forcibly recruited for combat.

"Many ended up leaving places close to the capital and retreating back into the core of Mesquita", says the researcher.

Others were expelled for failing to prove ownership of land destined for the construction of satellite towns. "The quilombola territory was disregarded in the Federal District's demarcation process", states the Incra report.

After the capital's construction, community land began to be coveted by outsiders.

"There was a lot of harassment for the sale of properties. Due to necessity, many villagers ended up disposing of them for ridiculous prices. They sold their land in order to buy medicine and clothes", says Neres.

Often land purchased from the quilombolas was soon resold. One of these transactions brought to the territory Maranhão politician José Sarney.

According to Incra's report, Sarney bought in the 1980's two land lots that had been expropriated from the community in the past. One of them gave rise to the Pecurimã farm he visited during the weekends while he was president.

In 2004, he sold the properties to Divitex Pericumã Empreendimentos Imobiliários, the real estate company of which he became a shareholder. Another partner of the company is attorney Antônio Carlos de Almeida Castro, known as Kakay, whose clients include several illustrious politicians in Brasília.

The periphery comes to Mesquita

In 1990, urbanization in the region increased with the creation of the Cidade Oriental municipality, a subdivision of Luziânia that received a habitation nucleus.

At one point quince cheese production was one of the main sources of income for Quilombo Mesquita. ANA CAROLINA A. FERNANDES

With the expansion of urban space, one housing project for low-income families — Jardim Edite — was built within the area originally claimed by the quilombo. In 2011, Incra excluded the public housing project from the territory in process of demarcation.

There are still several small farms within the territory claimed by the community. According to Incra, about 100 non-quilombola families lived in the area in 2011. Residents say the number is much higher now.

Demarcation

After the Constitution of 1988 determined the demarcation of quilombos, several communities mobilized to obtain land titles.

In Mesquita, the first step occured in 2006, when Fundação Cultural Palmares (the government body designed for promotion and preservation of Afro-Brazilian art and culture under the Ministry of Culture) recognized it as a remaining quilombo community.

Five years later, Incra published the community's Technical Report of Land Identification and Demarcation, defining its extension as 4300 hectares — the equivalent to 4000 football fields. According to Incra, the land claimed "represents only a fraction of the community's ancestral lands" and was delimited in order to guarantee the group's physical, social and cultural reproduction.

Then began the stage — which is not yet overcome — where non-quilombola residents and others interested in the territory can contest the report.

In order for the demarcation to be completed, the Presidency of the Republic must expropriate real estate within the territory and indemnify the owners. Only then can Incra give the community the collective and imprescriptible land title.

Sandra Braga says quilombolas still have not been recognized for their role in Brasília's founding. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

Of the approximately 3200 quilombos already recognized in Brazil, just over 200 have received land titles. Like in Mesquita's case, several processes are held back by impasses regarding expropriation and indemnification of non-quilombolas.

Reduction of the quilombo

The demarcation of the quilombo had an unfolding at the end of May, when Incra's Board of Directors issued a resolution authorizing the president of the government body to reduce the size of the territory to 971 hectares, 22% of the area originally planned.

The announcement was harshly criticized by quilombola associations. According to the National Coordination of Articulation of Black Rural Quilombola Communities (Conaq), the manoeuvre set a precedent for the reduction of other quilombos.

The resolution was also condemned by the Public Prosecutor's Office (MPF), which recomended its repeal. According to the government body, the decision "completely disregarded" studies conducted by Incra itself during the identification of the quilombo.

The oldest house in Quilombo Mesquita; with Brasília's founding, the value of land in the region has gone up. AGÊNCIA BRASIL

Last week, Incra announced that it would abide by MPF's suggestion and revoke the resolution while it rediscussed the case.

In a statement to BBC News Brasil, Incra said the reduction had been proposed by Quilombo Mesquita Renewal Association, a community organization of the quilombolas.

President of the association, Valcinei Batista Silva says the reduction would unlock the demarcation process and it is supported by the majority of the residents.

According to him, Incra's first intention to reserve 4300 hectares for the community proved to be unfeasible, since the government does not have the resources to expropriate all the non-quilombolas that live in the area.

Silva states that, should the proposed reduction be applied, the quilombolas would maintain all the territories they occupy now. "It is a proposal that allows Incra to work, send resources for expropriation and nobody would have to leave the land they're currently in."

Former president of the association, Sandra Pereira Braga says the current management's proposal does not have the support of the community and was articulated "in collusion with companies, farmers and speculators" interested in the territory.

"I have no doubt that there are powerful interests behind this", she says. "Most people in the community are totally against the reduction of territory — this is what Incra would find out had it consulted us before making any decisions."

Braga mentions, among those who would benefit from the reduction, Divitex Pecurimã — a company that has Sarney and Kakay as shareholders and would be, according to her, interested in building luxury condominiums in the territory.

With the growth of Brasília, a lot of areas around the capital began to host high-end housing complexes. At 40 km from the center of Brasília and near a highway that gives access to the city, the quilombo region would have huge potential for such enterprises, says Braga.

One of Sarney's press officers said the former president would not speak on the case. Kakay said he has never been to the region and does not follow the real estate company's administration, only acting as a "silent partner".

In a statement to BBC News Brasil, Divitex Pericumã Empreendimentos Imobiliários' attorney, Orlando Diniz Pinheiro, said that the company bought land in the region two years before the regularization of the quilombo began, and therefore "was not aware of the dispute (in relation to the territory)".

According to Pinheiro, quilombolas never inhabited the areas belonging to Divitex Pericumã. He says the company questions in court the land's inclusion in the area defined by Incra as the ancestral territory of the community.

The attorney says the land in process of demarcation "far exceeds the actual area where the Mesquita community resides". He says, however, that the company never exerted any pressure on government bodies for the quilombo to be reduced.

Pinheiro says the land possessed by the company is being leased for grain farming, but nothing prevents it from harboring real estate investments in the future — the activity mentioned in the company's corporate purpose.

"The families that are seeking demarcation have all purchased land in the region, they are not landowners in the quilombola area", states the attorney.

Quilombola Sandra Pereira Braga disputes the statement and says her ancestors have lived in the region for almost 300 years.

A line of candangos, the migrant workers that helped erect Brasília; city was built in less than four years. PUBLIC ARCHIVE OF THE FEDERAL DISTRICT

She says the quilombo celebrated the announcement that Incra would repeal the proposal to reduce the territory while the case was rediscussed, but the community will continue to mobilize until the withdrawal is definitive.

Braga says that, 58 years after Brasília's founding, the quilombo still fights for the recognition of its role in the construction of the city and, most importantly, for it to simply continue existing in the outskirts of the capital.

"If it wasn't for Mesquita, Brasília would not exist", she says.

The story of the quilombo that helped to build Brasília — and fears losing land to luxury condominiums

loyola llothta

☭☭☭

The Afro-descendant collective was the greatest beneficiary of this decade

In spite of the improvement of social indicators, they insist that there still is a "negrophobia"

TOMER URWICZ

According to the last national census, 8.1% of the population identifies as being of African descent. Photo: AFP

Behind the devotion for Negro Jefe, Negro Rada and Negro Ansina, Uruguay revealed its most racist facet: the terrible living conditions that gave birth to these three references and to many others. Ten years ago — almost nothing compared to three centuries of history — half of Afro-Uruguayans had at least one unmet basic need. At the end of 2017, however, they were one out of four.

It could be said that black people were discriminated against so much that any improvement would be significant. That is true. It may be justified that their living conditions — access to education, health and work — are still worse than those of the average Uruguayan. That is also true. But a report from the Ministry of Social Development (Mides), based on data provided by the Continuous Household Survey, shows that the Afro-descendant collective is the one that improved the most in the last decade if compared with itself.

In fact, in some indicators, the comparison is valid with regard to the rest of the population. At school completion, for example, Afro-Uruguayans have matched the national average; even when the completion of this educational level improved for all ethnicities and today is "almost universal".

Education is the field where improvement is most noticeable. In twelve years, this group doubled the percentage of its population that completes compulsory education. And according to nationalist deputy Gloria Rodríguez, the only Afro-descendant legislator, "today we find that many young people are continuing their tertiary studies and finishing them."

In addition to being a right, improving education for Afro-descendants "has a positive effect on global indicators of education", said Frederico Graña, director of Mides' Sociocultural Promotion. Particularly because Afro-Uruguayans "have, on average, more children than the average".

Some educational institutions, such as UTU, have set a particular incentive for people of African descent. Specifically, last November the Board of Professional Technical Education decided that at least 8% of scholarships would be destined for people belonging to this group.

According to the last national census, 8.1% of the Uruguayan population considers itself Afro-descendant. Hence the figure used for the minimum of scholarships as well as for the percentage of workers that government bodies must employ.

These proposals of "affirmative action are necessary, as a matter of fact it would be good to extend them to other fields", said deputy Rodríguez. However, the Mides data do not allow us to conclude whether the improvement in the quality of life of the Afro-descendant population is the result of "specific policies" or a "rebound effect" of improvements in the general population.

In the last three years, for example, the decline in poverty has been more significant among Afro-descendants than among non-blacks; this suggests something specific has happened in the collective. But health indicators, on the other hand, show that more and more Afro-descendants can be served by private mutual funds thanks to Fonasa (National Health Fund) and not a specific policy.

In this sense, the access of Afro-descendants to private healthcare providers had a behavior similar to that of the completion of compulsory education: it doubled in twelve years. Today, four out of ten Afro-Uruguayans are served by the Collective Medical Care Institutions (IAMC).

Whatever the reason for the improvement may be, Graña insists that "there is still a gap we haven't been able to eliminate". And the reason why the differences have not diminished with greater speed is because "society does not acknowledge racism".

The director of Sociocultural Promotion is taking advantage of this Afro-descendancy month to demonstrate how "Uruguay denies the existence of racism".

One evidence, he says, in Rivera's "duty-free shops there are no Afro-descendants serving the public, but an investigation by the University of the Republic did find many working inside the warehouses". This, according to Graña, makes it clear that "part of society defines good looking categories that are, in essence, racist".

Not to mention the cases of more direct discrimination, such as the attack an Afro-descendant worker received at a gas station at the end of June, Rodríguez recalled.

For the deputy there is no doubt: even if the quality of life is improved, "in Uruguay there still is negrophobia".

Only one government body met the inclusion quota

The law: Department of Cerro Largo hired 25% of Afro-descendant workers. Photo: Gerardo Pérez

Admission into government jobs for people of African descent and people with disabilities seems to suffer the same fate: government bodies fail to comply with quota regulations. Law 19.122 establishes that state institutions are obliged to allocate 8% of job vacancies to be filled in a year to be occupied by people of African descent by public call. But at the end of 2017, government agencies had only allocated 2.06%; according to the summary presented by the National Civil Service Office.

Percentage.

Only the Departmental Government of Cerro Largo complied with the law. Of all people admitted into the government body, one out of four were of African descent —in pratice this meant the hiring of three Afro-descendants. The other institutions that were close to reaching the goal were Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay (7.69%), the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (7.58%) and the Presidency of the Republic (7.16%).

In the legislative and judicial branches, the breach was huge, close to 100%. Something similar happened to Banco de Seguros, the state insurance company mentioned by Gloria Rodríguez to the Human Rights Commission of Deputies for alleged discrimination. What happened was they had made a public call but divided the applicants between black and non-black, ascribing each group to a different color. "It is clear that Afro-descendants are not being given the opportunities that were talked about so much".

"The same party (Broad Front) that promoted the law of Afro-descendants does not have any Afro-descendants occupying decision-making positions", said the nationalist deputy Gloria Rodríguez, the only black legislator holding office. This detail is, for her, a sign that "there is a need for positive discrimination... for a quota law". The idea would be similar to what already happens with the representation of women, but at a scale commensurate with the Afro-descendant population. Rodríguez has discussed the matter with other legislators, although she recognizes that there is no elaborate project "nor is it on the agenda". Rodríguez is convinced that a law of this type "should be only for a specific period of time, as an impulse and nothing more". The director of Sociocultural Promotion of Mides, Frederico Graña, is not convinced of the need for a quota law because, he says, that must come from the Afro-descendant community itself. But he said that in other countries, such as Colombia, there already are rules of this type.

A place beyond sports

In some departments of Uruguay, such as Artigas and Rivera, people of African descent exceed 17% of the local population. But the collective's visibility, says Graña, "almost always comes down to sports and culture". At most there is a third field of prominence, but it is linked to job opportunities: the military. In fact, the Ministry of Defense admitted last year 163 soldiers of African descent. And the percentage of this group that is treated in the military hospital exceeds the national average. The discrimination on the place assigned to Afro-descendants, says Graña, "is not a matter of the government in office, but that society does not manage to get rid of prejudices and with the expected place this population is supposed to develop".

The Afro-descendant collective was the greatest beneficiary of this decade

In spite of the improvement of social indicators, they insist that there still is a "negrophobia"

TOMER URWICZ

According to the last national census, 8.1% of the population identifies as being of African descent. Photo: AFP

Behind the devotion for Negro Jefe, Negro Rada and Negro Ansina, Uruguay revealed its most racist facet: the terrible living conditions that gave birth to these three references and to many others. Ten years ago — almost nothing compared to three centuries of history — half of Afro-Uruguayans had at least one unmet basic need. At the end of 2017, however, they were one out of four.

It could be said that black people were discriminated against so much that any improvement would be significant. That is true. It may be justified that their living conditions — access to education, health and work — are still worse than those of the average Uruguayan. That is also true. But a report from the Ministry of Social Development (Mides), based on data provided by the Continuous Household Survey, shows that the Afro-descendant collective is the one that improved the most in the last decade if compared with itself.

In fact, in some indicators, the comparison is valid with regard to the rest of the population. At school completion, for example, Afro-Uruguayans have matched the national average; even when the completion of this educational level improved for all ethnicities and today is "almost universal".

Education is the field where improvement is most noticeable. In twelve years, this group doubled the percentage of its population that completes compulsory education. And according to nationalist deputy Gloria Rodríguez, the only Afro-descendant legislator, "today we find that many young people are continuing their tertiary studies and finishing them."

In addition to being a right, improving education for Afro-descendants "has a positive effect on global indicators of education", said Frederico Graña, director of Mides' Sociocultural Promotion. Particularly because Afro-Uruguayans "have, on average, more children than the average".

Some educational institutions, such as UTU, have set a particular incentive for people of African descent. Specifically, last November the Board of Professional Technical Education decided that at least 8% of scholarships would be destined for people belonging to this group.

According to the last national census, 8.1% of the Uruguayan population considers itself Afro-descendant. Hence the figure used for the minimum of scholarships as well as for the percentage of workers that government bodies must employ.

These proposals of "affirmative action are necessary, as a matter of fact it would be good to extend them to other fields", said deputy Rodríguez. However, the Mides data do not allow us to conclude whether the improvement in the quality of life of the Afro-descendant population is the result of "specific policies" or a "rebound effect" of improvements in the general population.

In the last three years, for example, the decline in poverty has been more significant among Afro-descendants than among non-blacks; this suggests something specific has happened in the collective. But health indicators, on the other hand, show that more and more Afro-descendants can be served by private mutual funds thanks to Fonasa (National Health Fund) and not a specific policy.

In this sense, the access of Afro-descendants to private healthcare providers had a behavior similar to that of the completion of compulsory education: it doubled in twelve years. Today, four out of ten Afro-Uruguayans are served by the Collective Medical Care Institutions (IAMC).

Whatever the reason for the improvement may be, Graña insists that "there is still a gap we haven't been able to eliminate". And the reason why the differences have not diminished with greater speed is because "society does not acknowledge racism".

The director of Sociocultural Promotion is taking advantage of this Afro-descendancy month to demonstrate how "Uruguay denies the existence of racism".

One evidence, he says, in Rivera's "duty-free shops there are no Afro-descendants serving the public, but an investigation by the University of the Republic did find many working inside the warehouses". This, according to Graña, makes it clear that "part of society defines good looking categories that are, in essence, racist".

Not to mention the cases of more direct discrimination, such as the attack an Afro-descendant worker received at a gas station at the end of June, Rodríguez recalled.

For the deputy there is no doubt: even if the quality of life is improved, "in Uruguay there still is negrophobia".

Only one government body met the inclusion quota

The law: Department of Cerro Largo hired 25% of Afro-descendant workers. Photo: Gerardo Pérez

Admission into government jobs for people of African descent and people with disabilities seems to suffer the same fate: government bodies fail to comply with quota regulations. Law 19.122 establishes that state institutions are obliged to allocate 8% of job vacancies to be filled in a year to be occupied by people of African descent by public call. But at the end of 2017, government agencies had only allocated 2.06%; according to the summary presented by the National Civil Service Office.

Percentage.

Only the Departmental Government of Cerro Largo complied with the law. Of all people admitted into the government body, one out of four were of African descent —in pratice this meant the hiring of three Afro-descendants. The other institutions that were close to reaching the goal were Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay (7.69%), the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (7.58%) and the Presidency of the Republic (7.16%).

In the legislative and judicial branches, the breach was huge, close to 100%. Something similar happened to Banco de Seguros, the state insurance company mentioned by Gloria Rodríguez to the Human Rights Commission of Deputies for alleged discrimination. What happened was they had made a public call but divided the applicants between black and non-black, ascribing each group to a different color. "It is clear that Afro-descendants are not being given the opportunities that were talked about so much".

"The same party (Broad Front) that promoted the law of Afro-descendants does not have any Afro-descendants occupying decision-making positions", said the nationalist deputy Gloria Rodríguez, the only black legislator holding office. This detail is, for her, a sign that "there is a need for positive discrimination... for a quota law". The idea would be similar to what already happens with the representation of women, but at a scale commensurate with the Afro-descendant population. Rodríguez has discussed the matter with other legislators, although she recognizes that there is no elaborate project "nor is it on the agenda". Rodríguez is convinced that a law of this type "should be only for a specific period of time, as an impulse and nothing more". The director of Sociocultural Promotion of Mides, Frederico Graña, is not convinced of the need for a quota law because, he says, that must come from the Afro-descendant community itself. But he said that in other countries, such as Colombia, there already are rules of this type.

A place beyond sports

In some departments of Uruguay, such as Artigas and Rivera, people of African descent exceed 17% of the local population. But the collective's visibility, says Graña, "almost always comes down to sports and culture". At most there is a third field of prominence, but it is linked to job opportunities: the military. In fact, the Ministry of Defense admitted last year 163 soldiers of African descent. And the percentage of this group that is treated in the military hospital exceeds the national average. The discrimination on the place assigned to Afro-descendants, says Graña, "is not a matter of the government in office, but that society does not manage to get rid of prejudices and with the expected place this population is supposed to develop".

The Afro-descendant collective was the greatest beneficiary of this decade

Afro-Ecuadorian association supports the opening of three enterprises

Redacción Ecuador Regional - July 17 2018 - 00:00

Aída Quintero directed the event for the celebration of the first year of the Cámara Afro de Economía Popular y Solidaria association. Photo: William Orellana / EL TELÉGRAFO

This Saturday, the Cámara Afro de Economía Popular y Solidaria association celebrated the first anniversary of its founding with the inclusion of 20 organizations and the opening of three enterprises which employ about 70 Afro-Ecuadorians.

Aída Quintero, president of the association, explained that the institutioned was formed with the initiative of five members, facing the need for information regarding the creation of micro-enterprises.

"We did not know how the Government could help us or if we could work on our own to install productive businesses", said the leader.

The association began working with 14 organizations and currently there are 20, in addition to 2 natural persons. "We are all Afro-Ecuadorians from different parts of Guayaquil".

Quintero said that in these 12 months the main achievement of the institution has been remaining active not only with productive businesses, but also with the revival of Afro-descendant traditions through its members.

As far as the enterprises are concerned, she said that two organizations opened three businesses. One caterer, one cleaning business and one cleaning product selling business. She pointed out that this has been made possible with the sale of traditional products (cocada, coconut sweets, among others) at fairs.

"Before working as an association, our organizations took many years to establish themselves. We are self-employed people".

After this year, the goal of the institution is to continue helping its members. "We are not given opportunities, they declared an international decade for us but our activities are giving life to this decade".

Quintero expressed her wish that the organizations be given access loans to facilitate the opening of micro-enterprises. "We demand our right and we will wait for the doors to be opened, especially to the youth because many of them are unemployed".

Afro-Ecuadorian association supports the opening of three enterprises

Redacción Ecuador Regional - July 17 2018 - 00:00

Aída Quintero directed the event for the celebration of the first year of the Cámara Afro de Economía Popular y Solidaria association. Photo: William Orellana / EL TELÉGRAFO

This Saturday, the Cámara Afro de Economía Popular y Solidaria association celebrated the first anniversary of its founding with the inclusion of 20 organizations and the opening of three enterprises which employ about 70 Afro-Ecuadorians.

Aída Quintero, president of the association, explained that the institutioned was formed with the initiative of five members, facing the need for information regarding the creation of micro-enterprises.

"We did not know how the Government could help us or if we could work on our own to install productive businesses", said the leader.

The association began working with 14 organizations and currently there are 20, in addition to 2 natural persons. "We are all Afro-Ecuadorians from different parts of Guayaquil".

Quintero said that in these 12 months the main achievement of the institution has been remaining active not only with productive businesses, but also with the revival of Afro-descendant traditions through its members.

As far as the enterprises are concerned, she said that two organizations opened three businesses. One caterer, one cleaning business and one cleaning product selling business. She pointed out that this has been made possible with the sale of traditional products (cocada, coconut sweets, among others) at fairs.

"Before working as an association, our organizations took many years to establish themselves. We are self-employed people".

After this year, the goal of the institution is to continue helping its members. "We are not given opportunities, they declared an international decade for us but our activities are giving life to this decade".

Quintero expressed her wish that the organizations be given access loans to facilitate the opening of micro-enterprises. "We demand our right and we will wait for the doors to be opened, especially to the youth because many of them are unemployed".

Afro-Ecuadorian association supports the opening of three enterprises

Are the Caribbean's wealthy new citizens a lifeline or a liability?

JULY 19, 2018 / 12:02 PM

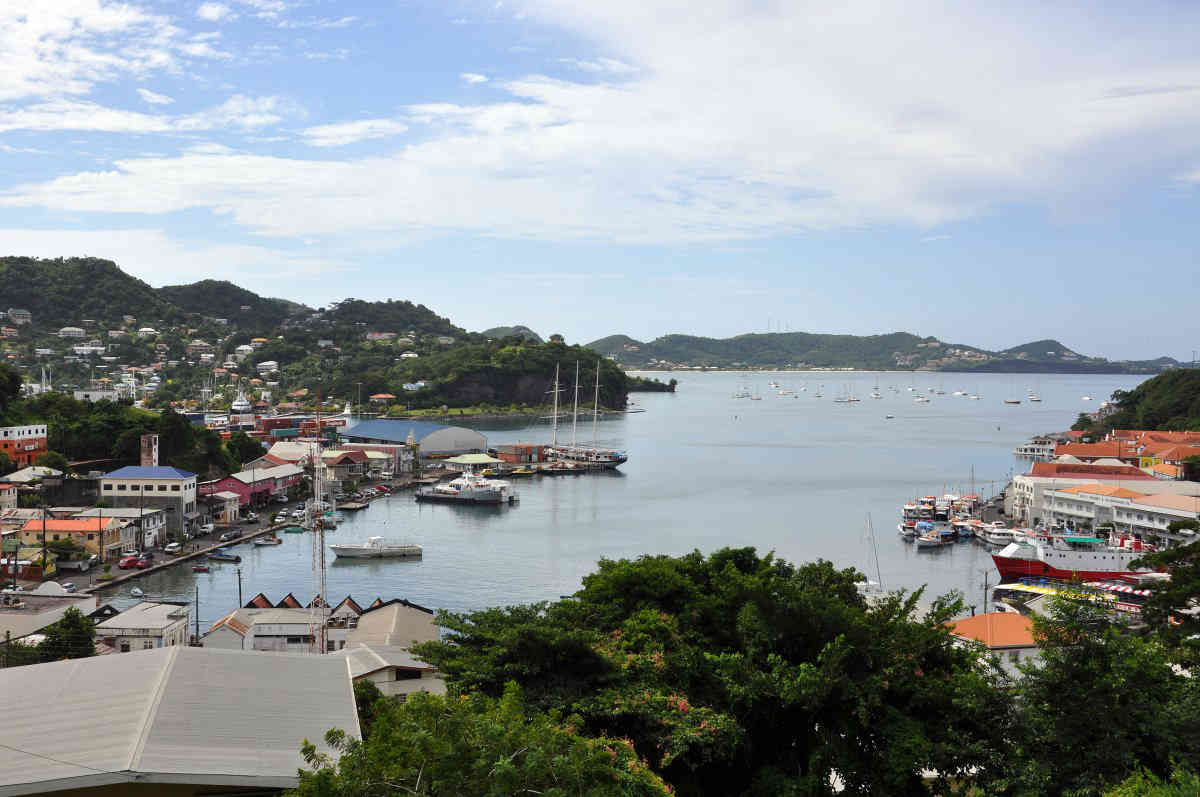

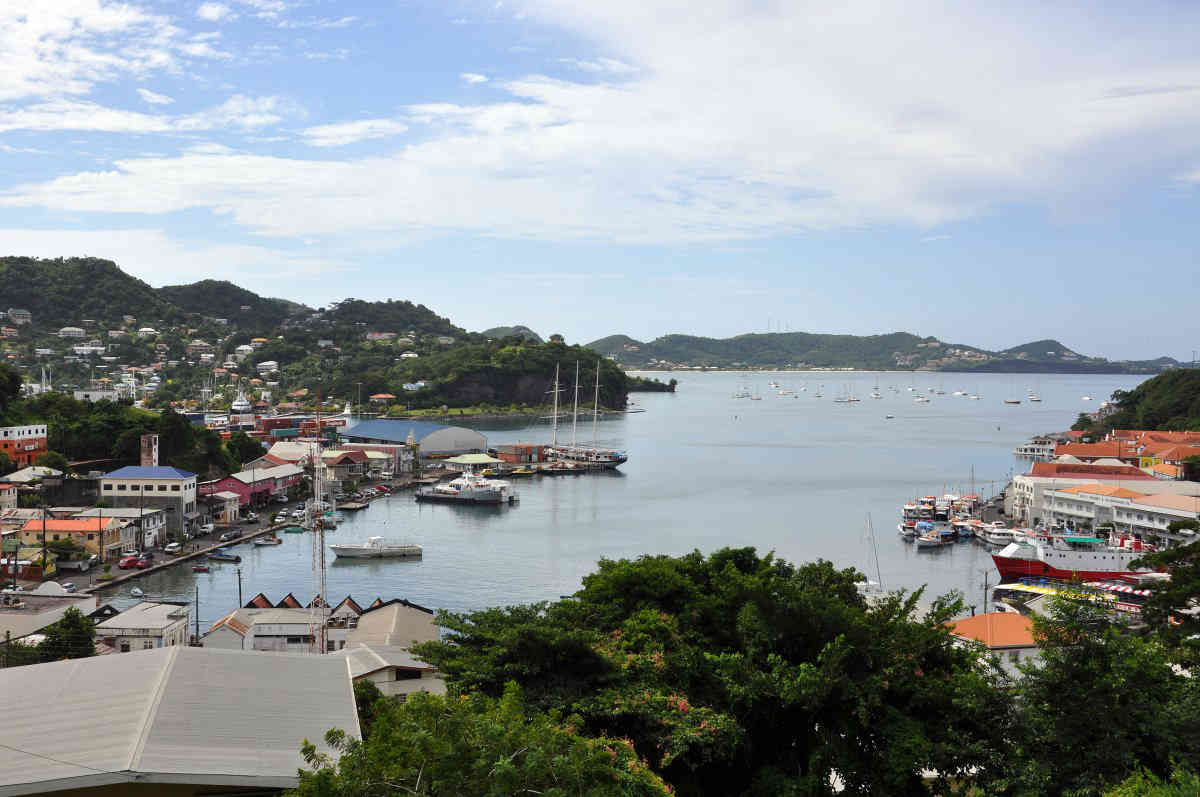

ST GEORGE’S, Grenada (Thomson Reuters Foundation) - Investing in the tropical Mount Cinnamon Resort in Grenada, with its white sand beaches, buys more than a slice of paradise - it comes with citizenship and a passport with visa-free entry to almost 130 countries.

People lounge at Mount Cinnamon Resort's beach club on Grand Anse beach in St. George's, the capital of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, June 1, 2018. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Sophie Hares

Few who take up the offer may ever visit their new homeland but for cash-strapped Caribbean states such as Grenada, “citizenship by investment” is a lucrative way to bankroll development and smart hotels, while chipping away at huge debts.

Grenada is one of a growing list of countries, including four others in the Caribbean, cashing in on a booming industry that offers citizenship or residency in return for investment as more people look for political and economic safe havens.

But the trend is also sparking concerns over global security and illicit financial activities, especially as small nations cut the price of citizenship as competition heats up and disasters hit their economies, boosting the need for fast funds.

Grenada’s Prime Minister Keith Mitchell said his country had gained massively since starting a program in 2014 whereby people can acquire citizenship for an investment from $150,000.

Applications rose 50 percent in 2017, according to a budget statement.

“It’s bringing in an enormous amount of money, and it’s helping us to reduce our debt burden in a very serious way,” said Mitchell, whose government is using 40 percent of citizenship revenues to pay off its debts.

“It’s making a significant contribution to the solutions to the problems in our country,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in a recent interview.

Saint Kitts and Nevis, Dominica, Antigua and Barbuda, and Saint Lucia are also tapping into the global citizenship market estimated by international advisory firms at $2 billion a year.

All those countries’ passports allow visa-free travel to the European Union.

But moves by several Caribbean nations to cut the price of citizenship late last year after hurricanes ravaged the region in September has raised concerns about the practice.

A string of scandals - including Iranians trying to evade sanctions, caught with Saint Kitts passports - has flagged the need to tighten checks and regulation otherwise countries in these schemes could see the money dry up, experts say.

“For those engaged in illicit finance or other forms of illegal activity, the new passport gives them, partially speaking, a new identity,” said Emanuele Ottolenghi, a senior fellow at U.S.-think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

That raises a potential “conflict of interest between the duty to do due diligence and the desire to leverage these programs for revenue” on the part of governments, he noted.

Government officials from Saint Kitts and Antigua were not available to comment, despite repeated requests.

People walk along a street in downtown St. George's, the capital of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, June 1, 2018. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Sophie Hares

Nationals of China and the Middle East are the biggest buyers of Caribbean citizenship, often sought by wealthy individuals seeking ease of travel or a “plan B” enabling a sharp exit for political reasons, said industry experts.

Various European nations including Britain, Spain and Malta, as well as New Zealand, Singapore and the United States have similar, albeit more expensive schemes, some of which require residency.

The relatively low cost of Caribbean citizenship, promoted at international fairs and advertised in glossy in-flight magazines, sets the islands apart from other countries.

Dominica charges $100,000, and Saint Kitts - which has the region’s longest-running program set up in 1984 - until recently offered citizenship for a family of four for a $150,000 donation to a hurricane relief fund.

In Grenada, to gain citizenship, investors can buy a $350,000 stake in a development like Mount Cinnamon, or donate $150,000 to a national transformation fund for the island.

“Ethically, morally, they’re investing in helping a developing nation ... creating jobs, creating tourism,” said Mark Scott, director of development at de Savary Properties, which owns Mount Cinnamon and wants to expand the resort.

‘RAINY DAY’

For some countries, citizenship programs have proved a cash lifeline. At one stage, they made up about a quarter of Saint Kitts’ income, allowing it to slash debt levels while financing the construction of luxury hotels.

The harbour is seen in St. George's, the capital of the Caribbean island nation of Grenada, June 1, 2018. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Sophie Hares

Range Developments, which built a five-star hotel on Saint Kitts and is now working on a new resort, said citizenship-by-investment funds covered about 65 percent of the cost of putting up the Park Hyatt, which has employed hundreds of local people.

“These programs are a major reason why we’re looking at the Caribbean,” Range director Mohammed Asaria told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone from Dubai.

Given the vulnerability of the region to extreme weather such as hurricanes and economic shocks, the Caribbean Development Bank wants governments to funnel a chunk of the revenue into “rainy day” sovereign wealth funds.

“These revenue flows can tend to fluctuate, so countries really shouldn’t become reliant on them for current expenditure,” said Justin Ram, the bank’s economics director.

LOOPHOLES

Brokers say applicants go through a rigorous three-stage process designed to weed out those on an international watch list, or looking to duck sanctions or launder money.

But others argue checks must be tighter to avoid scandals that could effectively slam the lid on the practice.

The U.S. State Department last year described Antigua’s citizenship program as “among the most lax in the world”.

In 2014, the U.S. Treasury Department warned banks that passports from Saint Kitts could be used for “illicit financial activity”.

The Iranian chairman of a Maltese bank, now awaiting trial in the United States on charges linked to a $115-million sanctions evasion scheme, was identified by the U.S. Department of Justice as using a passport from Saint Kitts.

Separately, Canada slapped visa requirements on Saint Kitts’ passport holders in 2014, after it said an Iranian entered the country on a diplomatic passport sold by the island state.

After that, Saint Kitts reprinted its passports to include the holder’s place of birth.