How the 19th-century flow of indentured workers shapes the Caribbean

Mar 11th 2017 | PORT OF SPAIN

Sources of tension include child marriage and terrorism. But mostly, people get on fine

WHEN Anthony Carmona, the president of Trinidad and Tobago, showed up in a Carnival parade last month wearing a head cloth, white shorts and beads like those worn by Hindu pandits, he was not expecting trouble. Nothing seems more Trinidadian than a mixed-race president joining a festival that has African and European roots. But some Hindus were outraged. “[O]ur dress code has never been associated with this foolish and self-degrading season,” huffed a priest. Trinidad’s cultures blend easily most of the time; occasionally, they strike sparks.

The Hindu-bead controversy is not the only one ruffling feelings among Indo-Trinidadians. Another is caused by a proposal in parliament to raise the minimum age for marriage to 18 for all citizens. Currently, Muslim girls can marry at 12, girls of other faiths at 14. Muslim and Hindu traditionalists want to keep it that way.

Another argument has been provoked by the disproportionate number of Trinidadians who have joined Islamic State (IS). About 130 of the country’s 1.3m people are thought to have fought for the “caliphate” or accompanied people who have. That is a bigger share of the population than in any country outside the Middle East. The government wants a new law to crack down on home-grown jihadists, which some Muslim groups denounce as discriminatory. The attorney-general, Faris Al-Rawi, is guiding both measures through the legislature.

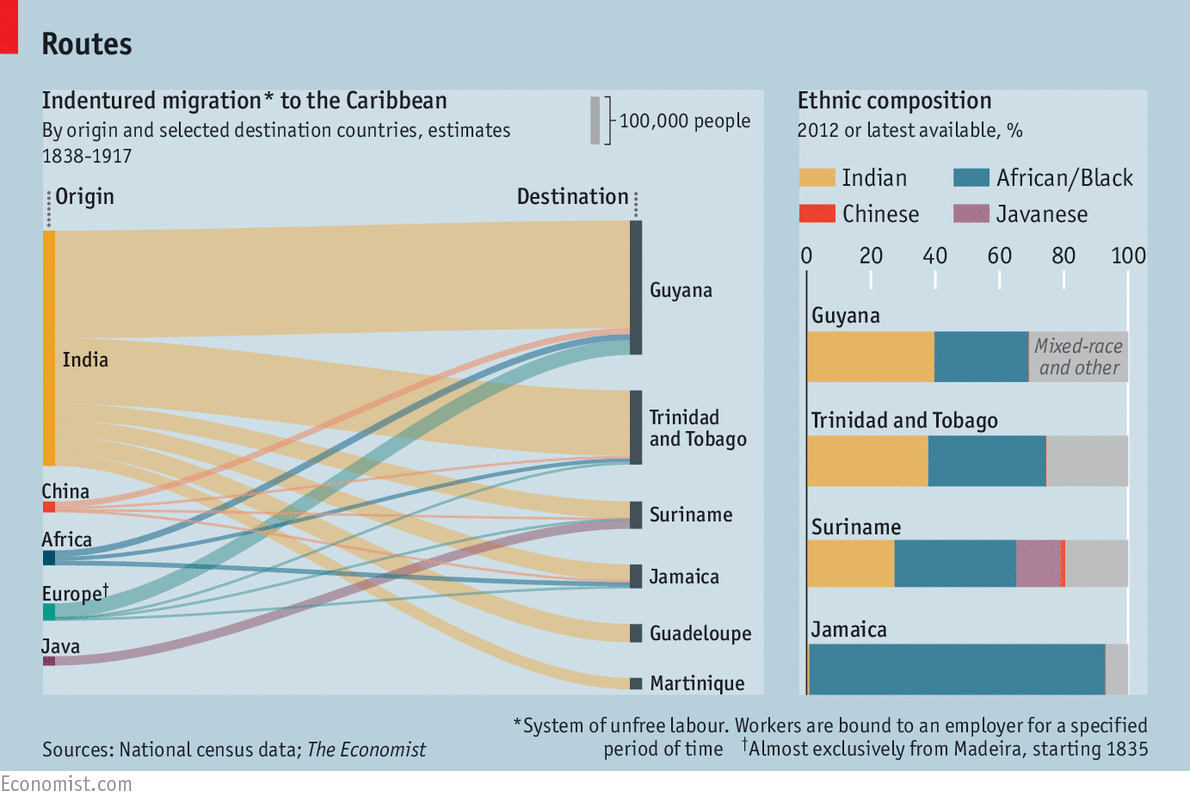

Both debates are causing unease in the communities that trace their origins to the influx of indentured workers in the 19th century. This month marks the 100th anniversary of the end of that flow. By bringing in large numbers of Indians, mostly Hindus and Muslims, the migration did much to shape the character of the Caribbean today (see chart). The arguments about marriage and terrorism are part of its legacy.

The migration from India began in 1838 as a way of replacing slavery, banned by Britain’s parliament five years earlier. Recruiters based in Calcutta trawled impoverished villages for workers willing to sign up for at least five years of labour—and usually ten—on plantations growing sugar, coconut and other crops in Trinidad, British Guiana (now Guyana), the Dutch colony of Suriname and elsewhere.

Workers were housed in fetid “coolie” barracks, many of which had served as slave quarters, and were paid a pittance of 25 cents a day, from which the cost of rations was deducted. Diseases like hookworm, caused by an intestinal parasite, were common.

But the labourers’ lot was better than that of enslaved Africans. Colonial governments in India and the Caribbean tried to prevent the worst abuses. Workers received some medical care and were not subject to the harsh punishments meted out to slaves, notes Radica Mahase, a historian. In some periods the colonial government offered workers inducements to stay at the end of a contract: five acres of land or five pounds in cash.

Opposition from Indian nationalists and shortages of shipping during the first world war prompted the British government of India to shut down the traffic on March 12th 1917. By then, more than half a million people had come to the Caribbean. Today, just over a third of Trinidad and Tobago’s people say they are of Indian origin, slightly more than the number of Afro-Trinidadians; the share is higher in Guyana, lower in Suriname. Hindus outnumber Muslims. Many, especially those whose forebears were educated at Presbyterian schools, are Christians.

Caribbean people of Indian origin are as successful and well-integrated as any social group. Many of Trinidad and Tobago’s state schools have religious affiliations but are ethnically mixed; the government pays most of their costs regardless of denomination. Eid al-Fitr, which celebrates the end of Ramadan, and Diwali are public holidays. Many Hindus celebrate the religious festival of Shivaratri, then join in Carnival parades. “An individual can have multiple identities,” says Ms Mahase.

Politics still has ethnic contours. In Trinidad and Tobago, most voters of African origin support the People’s National Movement, which is now in power. Indo-Trinidadians tend to back the opposition United National Congress. Guyana’s president, David Granger, is from a predominantly Afro-Guyanese party.

But these distinctions are blurring. A growing number of Caribbean people identify with neither group. Nearly 40% of teenagers in Trinidad and a quarter in Guyana call themselves mixed-race or “other”, or do not state their ethnicity in census surveys. When both countries hold elections in 2020, these young people are likely to vote less tribally than their parents do.

Trinidad’s jihadist problem is in part caused by the choice of new identities rather than by the embrace of established ones. Many of IS’s recruits are Afro-Trinidadian converts to Islam. Mr Al-Rawi, who is leading the fight to stop them, claims descent from the Prophet Muhammad through his Iraqi father, but has a more relaxed view of religion. His mother is Presbyterian, his wife is a Catholic of Syrian origin and one of his grandfathers was a Hindu.

The anti-terrorist and child-marriage laws he is promoting, though seemingly unrelated, are rebukes to rigid forms of identity. The anti-terrorist law would make it a criminal offence within Trinidad to join or finance a terrorist organisation or commit a terrorist act overseas. People travelling to designated areas, such as Raqqa in Syria, would have to inform security agencies before they go and when they come back. Imtiaz Mohammed of the Islamic Missionaries Guild denounces the proposed law as “draconian”.

The proposal to end child marriage affects few families; just 3,500 adolescents married between 1996 and 2016, about 2% of all marriages. But it has been just as contentious as the anti-terrorism law. The winning calypso at this year’s Carnival, performed by Hollis “Chalkdust” Liverpool, a former teacher, was called “Learn from Arithmetic”. Its refrain, “75 can’t go into 14”, mocked Hindu marriage customs and implicitly backed the legislation to raise the marriage age. Satnarayan Maharaj, an 85-year-old Hindu leader, called it an insult.

The government has enough votes in parliament to pass the law in its current form, but opponents may challenge it in the courts. Traditionalists may thus hold on to an anachronism imported from India, at least for a while. The bead-wearing, calypso-dancing president is probably a better guide to what the future holds.

This article appeared in the The Americas section of the print edition under the headline "Favouring curry"

How the 19th-century flow of indentured workers shapes the Caribbean

Unless you talking about African indentureds

Unless you talking about African indentureds