You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Essential Afro-Latino/ Caribbean Current Events

- Thread starter Poitier

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?8 People Weigh In On The Importance Of New York's Afro-Latino Festival

Festival-goers from countries all over the Americas talk about black latinx recognition.

By LUNA OLAVARRÍA GALLEGOS

Photographer RAFAEL RIO

This past weekend was the fourth annual Afro-Latino Fest in New York City, a cultural event aimed at bringing black latinx people together through music, dance, and talks. The festival brought together people from all over the world for a three-day dance extravaganza that featured traditional artists, DJs, and rappers playing showcases all right after one another.

In between sets by Nina Sky, DJ Jigüe and El Freaky, The FADER spoke to some of the people at the festival about why it was important for them to come out and represent last weekend. Here are eight fans on what afrolatinidad means to them.

1. Amanda, Afro-Brazilian

How is being Brazilian connected to afrolatinidad?

I consider myself Latina and I also consider myself Black. Brazil is part of Latin America, we were just conquered by different Europeans. Since I’m from Brazil, growing up here I was always torn. Black people would be like, “You’re not from here, you’re from Brazil, you’re Spanish,” and I would be like, “I don’t even speak Spanish.” Spanish-speaking Latinos would say, “You’re too Black.” Something like this, it helps all of us who have that lineage to find that community and that diaspora.

2. Michael, Afro-Puerto Rican

Tell me about what afrolatinidad means to you.

The legacy of the Afro-Latinos themselves is so vast and worldwide, that it’s great to have community and festivals like this that bring those people and cultures together. I’m Boricua, from the island of Puerto Rico, so this is close to my heart. I think the roots of our culture go back to Africa.

Why is this festival special to you?

This is close to my heart because my dad is a black Puerto Rican, my mom is a white Puerto Rican, so I'm Afro-Latino and I identify as Afro-Latino. Being here with people of similar backgrounds is always great. Just to see the different colors and shades is always a beautiful thing.

3. Tamara, African-American and Jamaican

[On Right]

How do you feel about this festival today?

I like this festival because it's traditional. I have never heard this kind of music before so it's exciting. It means a lot for me to be Jamaican and be here because I get to learn about my country.

4. Ozzy, Dominican

What does this festival mean to you?

This festival, culturally means a lot to me. When I was a kid back in the Dominican Republic I used to celebrate my culture with carnaval. Ever since I moved back to the states I haven’t done anything like that, so this is the first time in 10+ years that I have celebrated my culture.

What does it mean for you to be Dominican in New York City?

To some Dominicans, I’m not the most typical — I’m different. I don’t consider myself typical even though I am really proud of my culture and proud of where I come from. I don’t wear the flag all the time.

5. Touré Weaver, Black "New Jerseyan"

Why did you come out today?

I found out about this festival because of Que Bajo's mailing list, but I've been coming for a couple years and going to the different events because I like to hear the music, be with good people, and dance.

How do you see the connection between blackness and Latin America?

I've spent a lot of time in South America, in Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Ecuador. In most of those places there are pockets of African people. To see the way that music and different parts of the culture emanates throughout different parts of the culture is really cool.

6. Emiliana, Chilean-American

Why is this festival important to you?

I'm just really glad that this has been created. I think it's important that Afro-Latinos have this festival. Probably some of the artists that have influenced me the most, as an artist, are on this bill — Maluca, DJ Bembona, Nina Sky, Princess Nokia.

Where do you see the current conversation of afrolatinidad in your community?

Honestly, where I'm coming from on Staten Island, that conversation is not had enough. For where I live, I'm not encountering many Afro-Latinos, and that's the truth. I live in a predominantly Mexican and Albanian neighborhood, but I think it's something that needs to be spoken about where I'm from. In terms of having these conversations, we're a little bit behind. Things like this, festivals like this, as an artist, this is something I want to promote on [Staten] Island.

7. Jessica, Salvadorean

Why is this festival important to you?

As you can see, I am not dark skinned, but I am a Latina. I am Salvadorean, and I have a lot of cousins and family that are Afro-descendent. For me, it’s beautiful to see Latinos accepting their African culture.

What brought you out to this festival today?

I'm excited to hear Nina Sky, Maluca, Tito Puente Jr. I have been to Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico a lot and I am excited to see so many Caribbean Latinos here.

8. Rolando and Purple, Afro-Cuban, Jamaican, and Sicilian

Tell me about the importance of having this festival in New York City?

This is an opportunity for us to celebrate us as people. Being able to come together in New York, a community where the Afro-Latino community is big but not a lot of us are all connected to each other. It’s also an opportunity to share music and culture with the rest of New York. It's an opportunity to connect with the legacy.

Why is this festival important to you?

I have a daughter who is seven years old. She is Cuban, Jamaican, Sicilian, Black, and there’s a lot diversity in her, and without events like this, it’s a little harder to connect her to the diaspora. Events like this allow me to keep her connected.

July 12, 2016

ART, CARIBBEAN, POLITICS

8 People Weigh In On The Importance Of New York's Afro-Latino Festival

Festival-goers from countries all over the Americas talk about black latinx recognition.

By LUNA OLAVARRÍA GALLEGOS

Photographer RAFAEL RIO

This past weekend was the fourth annual Afro-Latino Fest in New York City, a cultural event aimed at bringing black latinx people together through music, dance, and talks. The festival brought together people from all over the world for a three-day dance extravaganza that featured traditional artists, DJs, and rappers playing showcases all right after one another.

In between sets by Nina Sky, DJ Jigüe and El Freaky, The FADER spoke to some of the people at the festival about why it was important for them to come out and represent last weekend. Here are eight fans on what afrolatinidad means to them.

1. Amanda, Afro-Brazilian

How is being Brazilian connected to afrolatinidad?

I consider myself Latina and I also consider myself Black. Brazil is part of Latin America, we were just conquered by different Europeans. Since I’m from Brazil, growing up here I was always torn. Black people would be like, “You’re not from here, you’re from Brazil, you’re Spanish,” and I would be like, “I don’t even speak Spanish.” Spanish-speaking Latinos would say, “You’re too Black.” Something like this, it helps all of us who have that lineage to find that community and that diaspora.

2. Michael, Afro-Puerto Rican

Tell me about what afrolatinidad means to you.

The legacy of the Afro-Latinos themselves is so vast and worldwide, that it’s great to have community and festivals like this that bring those people and cultures together. I’m Boricua, from the island of Puerto Rico, so this is close to my heart. I think the roots of our culture go back to Africa.

Why is this festival special to you?

This is close to my heart because my dad is a black Puerto Rican, my mom is a white Puerto Rican, so I'm Afro-Latino and I identify as Afro-Latino. Being here with people of similar backgrounds is always great. Just to see the different colors and shades is always a beautiful thing.

3. Tamara, African-American and Jamaican

[On Right]

How do you feel about this festival today?

I like this festival because it's traditional. I have never heard this kind of music before so it's exciting. It means a lot for me to be Jamaican and be here because I get to learn about my country.

4. Ozzy, Dominican

What does this festival mean to you?

This festival, culturally means a lot to me. When I was a kid back in the Dominican Republic I used to celebrate my culture with carnaval. Ever since I moved back to the states I haven’t done anything like that, so this is the first time in 10+ years that I have celebrated my culture.

What does it mean for you to be Dominican in New York City?

To some Dominicans, I’m not the most typical — I’m different. I don’t consider myself typical even though I am really proud of my culture and proud of where I come from. I don’t wear the flag all the time.

5. Touré Weaver, Black "New Jerseyan"

Why did you come out today?

I found out about this festival because of Que Bajo's mailing list, but I've been coming for a couple years and going to the different events because I like to hear the music, be with good people, and dance.

How do you see the connection between blackness and Latin America?

I've spent a lot of time in South America, in Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Ecuador. In most of those places there are pockets of African people. To see the way that music and different parts of the culture emanates throughout different parts of the culture is really cool.

6. Emiliana, Chilean-American

Why is this festival important to you?

I'm just really glad that this has been created. I think it's important that Afro-Latinos have this festival. Probably some of the artists that have influenced me the most, as an artist, are on this bill — Maluca, DJ Bembona, Nina Sky, Princess Nokia.

Where do you see the current conversation of afrolatinidad in your community?

Honestly, where I'm coming from on Staten Island, that conversation is not had enough. For where I live, I'm not encountering many Afro-Latinos, and that's the truth. I live in a predominantly Mexican and Albanian neighborhood, but I think it's something that needs to be spoken about where I'm from. In terms of having these conversations, we're a little bit behind. Things like this, festivals like this, as an artist, this is something I want to promote on [Staten] Island.

7. Jessica, Salvadorean

Why is this festival important to you?

As you can see, I am not dark skinned, but I am a Latina. I am Salvadorean, and I have a lot of cousins and family that are Afro-descendent. For me, it’s beautiful to see Latinos accepting their African culture.

What brought you out to this festival today?

I'm excited to hear Nina Sky, Maluca, Tito Puente Jr. I have been to Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico a lot and I am excited to see so many Caribbean Latinos here.

8. Rolando and Purple, Afro-Cuban, Jamaican, and Sicilian

Tell me about the importance of having this festival in New York City?

This is an opportunity for us to celebrate us as people. Being able to come together in New York, a community where the Afro-Latino community is big but not a lot of us are all connected to each other. It’s also an opportunity to share music and culture with the rest of New York. It's an opportunity to connect with the legacy.

Why is this festival important to you?

I have a daughter who is seven years old. She is Cuban, Jamaican, Sicilian, Black, and there’s a lot diversity in her, and without events like this, it’s a little harder to connect her to the diaspora. Events like this allow me to keep her connected.

July 12, 2016

ART, CARIBBEAN, POLITICS

8 People Weigh In On The Importance Of New York's Afro-Latino Festival

Suriname’s Bouterse: How do Caricom leaders sleep at nights? - Editorial - Jamaica Observer Mobile

nikka killed a bunch of protestors and they tryna sweep it under the rug

nikka killed a bunch of protestors and they tryna sweep it under the rug

nikka killed a bunch of protestors and they tryna sweep it under the rug

nikka killed a bunch of protestors and they tryna sweep it under the rugCrowdfunder: Preserving Afro-ecuadorian artistic heritage with “Palenques Culturales”

Latina Lista

Jul 12, 2016, 1:12 PM

LatinaLista — “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is a cultural center dedicated to the continuing artistic traditions of the Afroecuadorean town of Tambillo and its nationally renowned travelling marimba music and dance troupe Incrustados en el Manglar. This group provides an intergenerational link for the transmission of the oral and physical history of the town of Tambillo, allowing children of all ages a safe space to develop strong identities based in an awareness of their personal and cultural heritage.

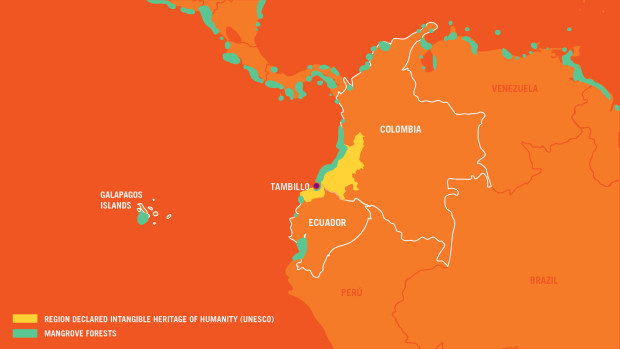

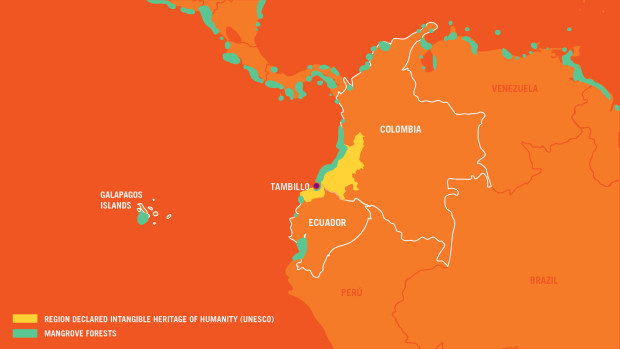

As part of a larger investigation of Afro-ecuadorean culture, its musical traditions and its present challenges, The Ochún Foundation, Caá Porá Architects and Siete86 Architects identified the town of Tambillo as an ideal place to begin the pilot program of “Palenques Culturales”. The “Palenques” project is dedicated to the creation of a network of cultural centers in communities that form part of the “region of the marimba” in the province of Esmeraldas, Ecuador. This cultural region was recently inscribed in 2015 as a part of the UNESCO list of the intangible heritage of humanity.

These celebrated traditions are at risk because of intra-generational learning gaps, immigration and other social factors.

The offices of Caá Porá, Siete86 and Ingeniera Alternativa began a process of a participatory research and design workshops with the community of Tambillo in October of 2015. These workshops have resulted in the design of a cultural complex composed of: a large performance and meeting hall, two multi-use classrooms and rehearsal spaces, an artisanal workshop for the fabrication of instruments and a block of public bathrooms using ecologically friendly water systems. These spaces have been designed taking into account the needs of the cultural group, the community infrastructure issues and the development of easily replicable construction technology for the future development of the community.

THE SITUATION

In 2005, Alfredo García, Héctor Ortiz and Malena Solís, all schoolteachers at the time, created the Incrustados en Manglar (loosely translated as Embedded in the Mangrove) association. This music and dance group accepts children between 5 and 19 years of age and is by far the largest youth group in the town of Tambillo. In the past decade this group has achieved national recognition for their touring shows and work preserving and growing the traditional, endemic marimba musical styles. The group has achieved this through grassroots community organization and support. The lack of external sponsorship has prevented the leaders of Incrustados en el Manglar from creating suitable infrastructure for teaching and performing. Currently they practice every afternoon on the cracked tile floor of the town municipal building.

This space is far from suitable for as a rehearsal space and presents strong challenges of size, upkeep, acoustics and temperature. Regardless of these difficulties, there are many children and adults that gather every evening, even outside looking in through the windows, to watch the development of original choreographies and musical themes.

Tambillo has an estimated population of 2,200 people currently, of which 60% are between the ages of 5 and 19. This imbalance results in social health problems such as: sexual violence and exploitation, intra-family violence, loss of self identity amongst youth and growth of gangs and violence, lack of self-identification in school materials and education, psychological abuse, teenage pregnancies, child labor amongst many others. Working with the children has been a huge part of this project, as they share their dreams and concerns as part of the design process.

THE PROJECT

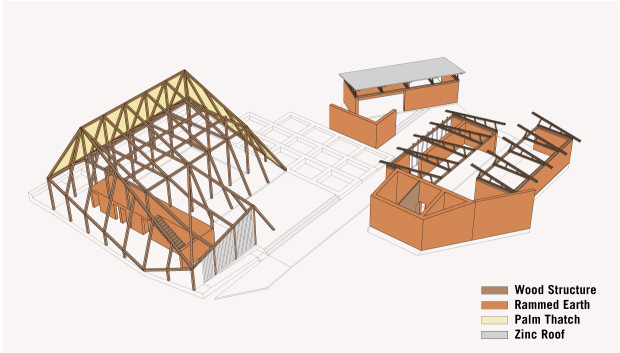

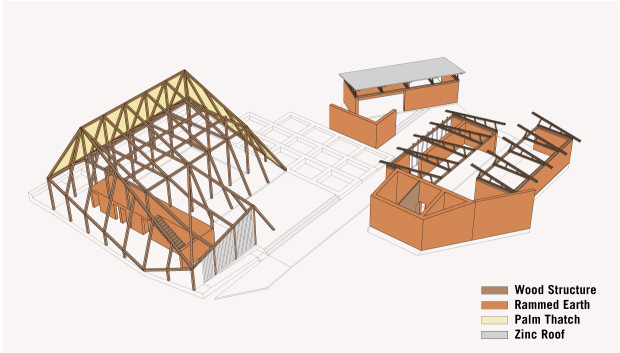

The design of the “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is the result of participatory workshops with the community and extensive architectural and social investigation by the Ochún Foundation, Caá Porá and Siete86. The main desire and need of the community was the construction of a space that represented their cultural history and construction methods. As architects we strove to understand the lengthy history, technical aspects and ceremonial significance of each material and spatial configuration. We interviewed master carpenters, fishermen and women, storytellers, dancers and musicians from Tambillo and the neighboring communities to understand the best woods for each phase of construction, traditional joinery methods and to understand the meaning and legends behind the music and dances.

We also investigated the ceremonial spaces of the African Diaspora and pre-colonial African civilizations in Cameroon, Nigeria, the Congo amongst others to understand spatial configuration and the ceremonial use of similar materials to those available in Tambillo. This process of the reconstruction of architectural ceremonial identities was inspired by the similar reconstruction of social and spiritual identity undertaken by many communities of the African Diaspora.

Based on this information we worked with engineers to devise modern and replicable construction solutions for the construction of the community center.

During the process of investigation, many of the community members in Tambillo let us visit their land to see what construction materials where locally available. The challenges of building in a protected ecological reserve and in a mangrove grove inspired engineering solutions and creative use of materials. One example of the solutions developed with our structural engineer is the use of oyster and conch shells that are discarded as part of the heavy fishing industry in Tambillo as additives to our rammed earth walls and concrete foundations. The main structure elements of the performance hall are locally and responsibly sourced wood. The roof of the dance hall is made of palm thatch, while the classrooms and workshops have zinc roofs with acoustical and thermal insulation.

The “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is designed as a refuge from the pressures of everyday life in Tambillo. The spaces are sheltered and conceived as a series of intimate and public courtyards. These flexible outdoor spaces are shaded and usable during the hot tropical days. Each building has a direct relationship with nature, and an important part of the project is the outside gardens that will function as nurseries for future reforestation initiatives.

The performance hall has a dance floor made of sand that hearkens to the traditional dances in outdoor spaces. The musicians are on a second level permitting clear sight lines for the spectators. The roof shell will conserve excellent acoustics while the palm thatch will absorb excess percussive sound. One side of the building is opened towards the mangroves to emphasize the direct relationship between the traditional storytelling role of the dances and the natural environment that inspires them.

The classrooms and workshops are more closely aligned to current local construction. They have been designed as examples of cost-accessible, earthquake-proof, easily constructed, climactically comfortable buildings using materials that can be locally sourced with minimal ecological impact. This is very important in Tambillo and other communities in the region where, because of social aspirations to homogenous modernity, concrete block has replaced much more cost and climactically efficient traditional forms of construction.

These buildings will be tools for the Incrustados en el Manglar group as they grow. The Ochún Foundation is assisting the members of this association in the legal process of becoming a foundation able to channel external resources to the community. The creation of a local foundation is an important aspect of this project, as it will permit local actors larger agency in the type of external investments that are realized in their community.

The campaign’s goal is $40,000.

Campaign: Palenque Tambillo: Afroecuadorian Cultural Center

Crowdfunder: Preserving Afro-ecuadorian artistic heritage with "Palenques Culturales"

Latina Lista

Jul 12, 2016, 1:12 PM

LatinaLista — “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is a cultural center dedicated to the continuing artistic traditions of the Afroecuadorean town of Tambillo and its nationally renowned travelling marimba music and dance troupe Incrustados en el Manglar. This group provides an intergenerational link for the transmission of the oral and physical history of the town of Tambillo, allowing children of all ages a safe space to develop strong identities based in an awareness of their personal and cultural heritage.

As part of a larger investigation of Afro-ecuadorean culture, its musical traditions and its present challenges, The Ochún Foundation, Caá Porá Architects and Siete86 Architects identified the town of Tambillo as an ideal place to begin the pilot program of “Palenques Culturales”. The “Palenques” project is dedicated to the creation of a network of cultural centers in communities that form part of the “region of the marimba” in the province of Esmeraldas, Ecuador. This cultural region was recently inscribed in 2015 as a part of the UNESCO list of the intangible heritage of humanity.

These celebrated traditions are at risk because of intra-generational learning gaps, immigration and other social factors.

The offices of Caá Porá, Siete86 and Ingeniera Alternativa began a process of a participatory research and design workshops with the community of Tambillo in October of 2015. These workshops have resulted in the design of a cultural complex composed of: a large performance and meeting hall, two multi-use classrooms and rehearsal spaces, an artisanal workshop for the fabrication of instruments and a block of public bathrooms using ecologically friendly water systems. These spaces have been designed taking into account the needs of the cultural group, the community infrastructure issues and the development of easily replicable construction technology for the future development of the community.

THE SITUATION

In 2005, Alfredo García, Héctor Ortiz and Malena Solís, all schoolteachers at the time, created the Incrustados en Manglar (loosely translated as Embedded in the Mangrove) association. This music and dance group accepts children between 5 and 19 years of age and is by far the largest youth group in the town of Tambillo. In the past decade this group has achieved national recognition for their touring shows and work preserving and growing the traditional, endemic marimba musical styles. The group has achieved this through grassroots community organization and support. The lack of external sponsorship has prevented the leaders of Incrustados en el Manglar from creating suitable infrastructure for teaching and performing. Currently they practice every afternoon on the cracked tile floor of the town municipal building.

This space is far from suitable for as a rehearsal space and presents strong challenges of size, upkeep, acoustics and temperature. Regardless of these difficulties, there are many children and adults that gather every evening, even outside looking in through the windows, to watch the development of original choreographies and musical themes.

Tambillo has an estimated population of 2,200 people currently, of which 60% are between the ages of 5 and 19. This imbalance results in social health problems such as: sexual violence and exploitation, intra-family violence, loss of self identity amongst youth and growth of gangs and violence, lack of self-identification in school materials and education, psychological abuse, teenage pregnancies, child labor amongst many others. Working with the children has been a huge part of this project, as they share their dreams and concerns as part of the design process.

THE PROJECT

The design of the “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is the result of participatory workshops with the community and extensive architectural and social investigation by the Ochún Foundation, Caá Porá and Siete86. The main desire and need of the community was the construction of a space that represented their cultural history and construction methods. As architects we strove to understand the lengthy history, technical aspects and ceremonial significance of each material and spatial configuration. We interviewed master carpenters, fishermen and women, storytellers, dancers and musicians from Tambillo and the neighboring communities to understand the best woods for each phase of construction, traditional joinery methods and to understand the meaning and legends behind the music and dances.

We also investigated the ceremonial spaces of the African Diaspora and pre-colonial African civilizations in Cameroon, Nigeria, the Congo amongst others to understand spatial configuration and the ceremonial use of similar materials to those available in Tambillo. This process of the reconstruction of architectural ceremonial identities was inspired by the similar reconstruction of social and spiritual identity undertaken by many communities of the African Diaspora.

Based on this information we worked with engineers to devise modern and replicable construction solutions for the construction of the community center.

During the process of investigation, many of the community members in Tambillo let us visit their land to see what construction materials where locally available. The challenges of building in a protected ecological reserve and in a mangrove grove inspired engineering solutions and creative use of materials. One example of the solutions developed with our structural engineer is the use of oyster and conch shells that are discarded as part of the heavy fishing industry in Tambillo as additives to our rammed earth walls and concrete foundations. The main structure elements of the performance hall are locally and responsibly sourced wood. The roof of the dance hall is made of palm thatch, while the classrooms and workshops have zinc roofs with acoustical and thermal insulation.

The “Palenque Cultural Tambillo” is designed as a refuge from the pressures of everyday life in Tambillo. The spaces are sheltered and conceived as a series of intimate and public courtyards. These flexible outdoor spaces are shaded and usable during the hot tropical days. Each building has a direct relationship with nature, and an important part of the project is the outside gardens that will function as nurseries for future reforestation initiatives.

The performance hall has a dance floor made of sand that hearkens to the traditional dances in outdoor spaces. The musicians are on a second level permitting clear sight lines for the spectators. The roof shell will conserve excellent acoustics while the palm thatch will absorb excess percussive sound. One side of the building is opened towards the mangroves to emphasize the direct relationship between the traditional storytelling role of the dances and the natural environment that inspires them.

The classrooms and workshops are more closely aligned to current local construction. They have been designed as examples of cost-accessible, earthquake-proof, easily constructed, climactically comfortable buildings using materials that can be locally sourced with minimal ecological impact. This is very important in Tambillo and other communities in the region where, because of social aspirations to homogenous modernity, concrete block has replaced much more cost and climactically efficient traditional forms of construction.

These buildings will be tools for the Incrustados en el Manglar group as they grow. The Ochún Foundation is assisting the members of this association in the legal process of becoming a foundation able to channel external resources to the community. The creation of a local foundation is an important aspect of this project, as it will permit local actors larger agency in the type of external investments that are realized in their community.

The campaign’s goal is $40,000.

Campaign: Palenque Tambillo: Afroecuadorian Cultural Center

Crowdfunder: Preserving Afro-ecuadorian artistic heritage with "Palenques Culturales"

1915-2015: One hundred years of US occupation in Haiti

• Originally published July 28, 2015

THE CENTENNIAL ANNIVERSARY of the US invasion of Haiti, which began on this day in 1915, will go largely unnoticed in the US.

Even for those Americans willing to face their country’s historical misdeeds, the occupation of Haiti gets easily lost among the military adventurism in Latin America and the Caribbean – the so-called ‘Banana Wars’ – that characterized US foreign policy during its ascendance as a superpower in the early twentieth century.

Not so in Haiti. Even though the country is gearing up for the first elections in almost five years, and though the threat of waves of deportees arriving from the Dominican Republic remains, plenty of attention is still reserved for marking the anniversary of the American occupation.

A ceremony will take place today to honor the Haitian soldiers who resisted the occupation; several international symposia have taken place or are being planned to discuss its history and legacy; and later this year, a ‘symbolic tribunal’ will be held to judge the various personalities involved in placing Haiti under the yoke of occupation.

For many of the organizers of these events, the purpose is not simply to remember a chapter of Haiti’s history. Rather, it is to highlight the legacy of the Occupation and those consequences which still linger today. The Mouvman Patriyotik Demokratik Popilè (Popular Patriotic Democratic Movement), which has been promoting several of the events as part of a ‘Mobilization Week’ to mark the 100th anniversary of the Occupation, is using the slogan “1915-2015: With or without boots, the Occupation is still here.”

In a very literal sense, Haiti is under occupation today, this time by the United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti (known by its French acronym MINUSTAH), a peacekeeping force that has occupied the country since 2004.

Its legacy in Haiti includes inadvertently starting a cholera epidemic, and a slew of sexualexploitation and abuse incidents which MINUSTAH soldiers make little attempt to cover up —in one infamous incident, they even videotaped themselves — because the terms of the mission give them legal immunity in Haiti. Even so, a former US ambassador to Haiti is on record calling MINUSTAH “an indispensable tool in realizing core US government policy interests in Haiti.”

And while MINUSTAH is something of an aberration in UN history – never has so large a force been deployed for so long in a country that was not at war – it is certainly not an aberration in Haitian history. It is just the latest link in an almost unbroken chain that stretches back at least as far as the US Occupation that began 100 years ago.

***

Although the US Occupation officially began in July of 1915, the groundwork had been laid several years prior. The ‘Dollar Diplomacy’ strategy of the Taft Administration had encouraged US banks to lend money to Caribbean republics as a way of increasing US influence over them.

Knowing that many banks would be hesitant to lend to governments perceived as ‘immature’ or unstable, the US government often gave its explicit backing to the banks. The US would then leverage the banks’ support to Caribbean governments to demand control over a debtor country’s trade policies, or to secure concessions for other US companies.

In the early 1910s, National City Bank – today known as Citibank – was becoming increasingly involved in Haiti, and, because of its importance to the Dollar Diplomacy strategy, the potential inability of the Haitian government to repay National City Bank became a matter of US national interest. Thus on December 17, 1914, the USS Machias landed in Port-au-Prince, and American troops marched to the National Bank of Haiti and carried away $500,000, which was then delivered to National City Bank in New York.

In addition to this mounting external pressure, Haiti was also suffering a string of internal political crises. In February 1915, President Theodore Davilmar – who had come to power through an armed revolt only a year before – was forced to resign, and a new president, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, was elected.

The US sent an envoy to Haiti to inform the new president that his government would not be recognized by the US unless he signed an accord giving the US control over the country’s customs regime – an agreement similar to the one the US had obtained from the neighboring Dominican Republic in 1907.

When former President Davilmar, had been offered the same choice – diplomatic isolation or cessation of control over his country’s customs and finances – he flatly rebuffed the Americans, saying “The Government of the Republic of Haiti would consider itself lax in its duty to the United States and to itself if it allowed the least doubt to exist of its irrevocable intention not to accept any control of the administration of Haitian affairs by a foreign Power.” But the new President Sam was willing to negotiate. He made several counter-proposals to the US envoy, which where were then sent back to Washington.

President Sam’s willingness to negotiate ceding control of his country’s affairs to the US had earned him Washington’s trust, but it made him, unsurprisingly, very unpopular in Haiti. As discontent mounted, and the threat of a popular uprising against him became ever more credible, Sam decided to go on the offensive: On July 27, he ordered the killing of 167 political prisoners, among them another former President.

Whatever support Sam still had among the population evaporated after this massacre, and he was forced to flee the Presidential Palace, seeking refuge in the French embassy. The next day, July 28, he was dragged from the embassy and beaten to death by an angry crowd.

Sam’s assassination had deprived the US of its most pliable ally in years, but it also provided the pretext for an invasion for which President Woodrow Wilson’s administration had been waiting. Within hours of Sam’s death, US Marines had come ashore and taken control of the capital. Martial law was declared, and a 19-year occupation began.

‘Civilising’ Haitian people

The US Occupation was justified through a flurry of paternalistic rhetoric that seized on the purported inability of an uneducated people to manage their own affairs. Robert Lansing, then Secretary of State, justified the occupation on the grounds that Haitians were still primitive Africans and therefore incapable of self-government; they had, he said, an “an inherent tendency toward savagery and a physical inability to live a civilized life.”

Medill McCormick, a Senator from Illinois wrote in 1920 that the American occupation was necessary “to develop the country, the Government, and above all, the civilization of the people, of whom the overwhelming majority have African blood in their veins.”

“We are there, and in my judgment we ought to stay there for twenty years…There is a need for merchants, for telegraph and cable facilities, for regular shipping. Private enterprise ought to march with the enlightened “occupation” under a new administration. We are proud of our service to Cuba. There is a greater service to be rendered and as great a harvest to be gathered in Haiti and Santo Domingo”

— U.S. Senator Medill McCormick, 1920

The opportunity to develop a “primitive” country, free from the impediments that a sovereign government might impose, prompted a great deal of enthusiasm. By the time of McCormick’s writing in 1920, the ability of American private enterprise to gather the harvest that Haiti offered had been facilitated by the occupiers’ re-writing of Haiti’s constitution.

Plundering Haiti

Ever since Haiti’s independence from France, foreign ownership of land had been constitutionally prohibited. Some German merchants had gotten around this prohibition by marrying Haitians and owning property through their spouses, but for an American psyche still shaped by the segregationist racial attitudes of the early 1900’s, mingling with the local population was not an option. In any case, as the rulers of a country under martial law, the US no longer needed to resort to careful manipulation.

Marines with installed President, Sudre Dartiguenave

• Originally published July 28, 2015

THE CENTENNIAL ANNIVERSARY of the US invasion of Haiti, which began on this day in 1915, will go largely unnoticed in the US.

Even for those Americans willing to face their country’s historical misdeeds, the occupation of Haiti gets easily lost among the military adventurism in Latin America and the Caribbean – the so-called ‘Banana Wars’ – that characterized US foreign policy during its ascendance as a superpower in the early twentieth century.

Not so in Haiti. Even though the country is gearing up for the first elections in almost five years, and though the threat of waves of deportees arriving from the Dominican Republic remains, plenty of attention is still reserved for marking the anniversary of the American occupation.

A ceremony will take place today to honor the Haitian soldiers who resisted the occupation; several international symposia have taken place or are being planned to discuss its history and legacy; and later this year, a ‘symbolic tribunal’ will be held to judge the various personalities involved in placing Haiti under the yoke of occupation.

For many of the organizers of these events, the purpose is not simply to remember a chapter of Haiti’s history. Rather, it is to highlight the legacy of the Occupation and those consequences which still linger today. The Mouvman Patriyotik Demokratik Popilè (Popular Patriotic Democratic Movement), which has been promoting several of the events as part of a ‘Mobilization Week’ to mark the 100th anniversary of the Occupation, is using the slogan “1915-2015: With or without boots, the Occupation is still here.”

In a very literal sense, Haiti is under occupation today, this time by the United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti (known by its French acronym MINUSTAH), a peacekeeping force that has occupied the country since 2004.

Its legacy in Haiti includes inadvertently starting a cholera epidemic, and a slew of sexualexploitation and abuse incidents which MINUSTAH soldiers make little attempt to cover up —in one infamous incident, they even videotaped themselves — because the terms of the mission give them legal immunity in Haiti. Even so, a former US ambassador to Haiti is on record calling MINUSTAH “an indispensable tool in realizing core US government policy interests in Haiti.”

And while MINUSTAH is something of an aberration in UN history – never has so large a force been deployed for so long in a country that was not at war – it is certainly not an aberration in Haitian history. It is just the latest link in an almost unbroken chain that stretches back at least as far as the US Occupation that began 100 years ago.

***

Although the US Occupation officially began in July of 1915, the groundwork had been laid several years prior. The ‘Dollar Diplomacy’ strategy of the Taft Administration had encouraged US banks to lend money to Caribbean republics as a way of increasing US influence over them.

Knowing that many banks would be hesitant to lend to governments perceived as ‘immature’ or unstable, the US government often gave its explicit backing to the banks. The US would then leverage the banks’ support to Caribbean governments to demand control over a debtor country’s trade policies, or to secure concessions for other US companies.

In the early 1910s, National City Bank – today known as Citibank – was becoming increasingly involved in Haiti, and, because of its importance to the Dollar Diplomacy strategy, the potential inability of the Haitian government to repay National City Bank became a matter of US national interest. Thus on December 17, 1914, the USS Machias landed in Port-au-Prince, and American troops marched to the National Bank of Haiti and carried away $500,000, which was then delivered to National City Bank in New York.

In addition to this mounting external pressure, Haiti was also suffering a string of internal political crises. In February 1915, President Theodore Davilmar – who had come to power through an armed revolt only a year before – was forced to resign, and a new president, Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, was elected.

The US sent an envoy to Haiti to inform the new president that his government would not be recognized by the US unless he signed an accord giving the US control over the country’s customs regime – an agreement similar to the one the US had obtained from the neighboring Dominican Republic in 1907.

When former President Davilmar, had been offered the same choice – diplomatic isolation or cessation of control over his country’s customs and finances – he flatly rebuffed the Americans, saying “The Government of the Republic of Haiti would consider itself lax in its duty to the United States and to itself if it allowed the least doubt to exist of its irrevocable intention not to accept any control of the administration of Haitian affairs by a foreign Power.” But the new President Sam was willing to negotiate. He made several counter-proposals to the US envoy, which where were then sent back to Washington.

President Sam’s willingness to negotiate ceding control of his country’s affairs to the US had earned him Washington’s trust, but it made him, unsurprisingly, very unpopular in Haiti. As discontent mounted, and the threat of a popular uprising against him became ever more credible, Sam decided to go on the offensive: On July 27, he ordered the killing of 167 political prisoners, among them another former President.

Whatever support Sam still had among the population evaporated after this massacre, and he was forced to flee the Presidential Palace, seeking refuge in the French embassy. The next day, July 28, he was dragged from the embassy and beaten to death by an angry crowd.

Sam’s assassination had deprived the US of its most pliable ally in years, but it also provided the pretext for an invasion for which President Woodrow Wilson’s administration had been waiting. Within hours of Sam’s death, US Marines had come ashore and taken control of the capital. Martial law was declared, and a 19-year occupation began.

‘Civilising’ Haitian people

The US Occupation was justified through a flurry of paternalistic rhetoric that seized on the purported inability of an uneducated people to manage their own affairs. Robert Lansing, then Secretary of State, justified the occupation on the grounds that Haitians were still primitive Africans and therefore incapable of self-government; they had, he said, an “an inherent tendency toward savagery and a physical inability to live a civilized life.”

Medill McCormick, a Senator from Illinois wrote in 1920 that the American occupation was necessary “to develop the country, the Government, and above all, the civilization of the people, of whom the overwhelming majority have African blood in their veins.”

“We are there, and in my judgment we ought to stay there for twenty years…There is a need for merchants, for telegraph and cable facilities, for regular shipping. Private enterprise ought to march with the enlightened “occupation” under a new administration. We are proud of our service to Cuba. There is a greater service to be rendered and as great a harvest to be gathered in Haiti and Santo Domingo”

— U.S. Senator Medill McCormick, 1920

The opportunity to develop a “primitive” country, free from the impediments that a sovereign government might impose, prompted a great deal of enthusiasm. By the time of McCormick’s writing in 1920, the ability of American private enterprise to gather the harvest that Haiti offered had been facilitated by the occupiers’ re-writing of Haiti’s constitution.

Plundering Haiti

Ever since Haiti’s independence from France, foreign ownership of land had been constitutionally prohibited. Some German merchants had gotten around this prohibition by marrying Haitians and owning property through their spouses, but for an American psyche still shaped by the segregationist racial attitudes of the early 1900’s, mingling with the local population was not an option. In any case, as the rulers of a country under martial law, the US no longer needed to resort to careful manipulation.

Marines with installed President, Sudre Dartiguenave

In 1917, the US State Department submitted a proposal to amend Haiti’s Constitution to allow foreigners to own land. When Haiti’s National Assembly refused to approve it, the occupying force disbanded the legislature and would not allow it to reconvene for the next 12 years.

The US quickly organized a ‘popular referendum’ to approve the new constitution, and it was accepted in a sham vote in which less than 5% of the population participated. The restraints were off and Haiti was finally for sale to outside investors.

Aside from the obvious afflictions visited upon a people living under foreign military occupation – routine physical violence, sexual assault, and stifling media censorship to name a few – Haitians suffered countless other indignations during the Occupation.

Bureaucrats were imported from the US to manage Haiti, and their extravagant salaries were paid directly from the Haitian treasury. Meanwhile, Haitian functionaries doing the same work were paid far less. In the countryside, able-bodied Haitian men were rounded up and forced into hard labour, often building roads through land that had been seized from them by the Marines.

Such a heavy-handed occupation could only provoke discontent and uprisings, but the beleaguered and impoverished Haitian masses were ultimately no match for a few thousand heavily-armed American Marines, or for the Gendarmerie, a force composed of both Americans and Haitians that the Occupation used to quell rebellions and put down protests.

Ending the official occupation

Even though the Haitian resistance produced a number of charismatic and quixotic figures, what ultimately brought about the end of US military occupation was not any defeat suffered by the Marines; rather it was their success in crushing the discontented masses with increasingly brutal efficiency.

On December 6, 1929, Marines opened fire on an unarmed crowd of protesters in Les Cayes, killing at least a dozen people. The Cayes Massacre attracted plenty of unfavorable attention from international newspapers, and provoked protests within the US against the Occupation of Haiti.

The Occupation had become increasingly unpopular, but it was also becoming less profitable: the Great Depression and the collapse of commodity markets had caused a steep fall in the price of coffee, which was the Haitian economy’s principal export.

Faced with diminishing returns, President Herbert Hoover had no enthusiasm for prolonging any further the Occupation that he had inherited, and declared in February of 1930: “The primary question which is to be investigated is when and how we are to withdraw from Haiti. The second question is what we shall do in the meantime.”

Enduring legacy of occupation

Despite the pressure to withdraw, the Occupation force had become so thoroughly embedded in every aspect of Haitian life that it was not easy for the US to extricate itself. The Marines would not leave Haiti until August 15, 1934 and the US would maintain direct control of Haiti’s external finances until 1947. But even then, the Occupation was not really over.

In the years that followed, the Gendarmerie – the American-trained force created during the Occupation – became the principal power broker in Haitian politics. Presidents were imposed and deposed by the Gendarmerie through a series of bloody coups d’états; three of the military strongmen who assumed power during the tumultuous 1950s were graduates of the American Military School in Haiti that had been set up during the Occupation.

Quite evidently, the stated goal of the US Occupation – to bring ‘stability’ to Haiti – had failed spectacularly. In fact, the revolving door of warrior presidents wouldn’t end until 1957 with the rise to power of “President for Life” Francois ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, a brutal dictator who won US support because of his anti-Communist rhetoric.

Yet it seems rather naïve to describe the Occupation of Haiti as a failure for the promotion of US’ interests. Indeed, far from being“America’s least successful experiment in imperialism” as The Guardian described it at the time, the Occupation of Haiti seems to have been one of the most enduring.

The US remains deeply implicated in Haiti’s economy, and still insists on the right to intervene for the benefit of US corporations. In 2009 when the Haitian government passed a measure to raise the country’s meagre minimum wage from 24 cents an hour to 61 cents an hour, several US-based garment manufacturers that have factories in Haiti – including Levi’s, Hanes and Fruit of the Loom – protested to the US embassy in Port-au-Prince. The US Ambassador then pressured René Préval, Haiti’s President at the time, to halt the increase from going into effect. As a result, the Haitian government agreed to limit the minimum wage to 31 cents per hour.

Although such interventions are certainly less dramatic than troops marching on the National Bank, the resulting transfer of wealth from Haitians to US corporations is no less so.

And the US has also continued to maintain multiple levers for manipulating Haitian politics: forming paramilitary groups, intervening to influence elections, and buying support from Haitian politicians (including the current President) through USAID.

Supporters of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who accused the US of deposing him in a coup, protest the US at OAS Summit / Danny Hammontree

It is not difficult to see other echoes of the Occupation’s logic in Haiti today: That expats deserve higher salaries than Haitian staff doing the same work remains an article of faith both for official aid agencies and the many international NGOs operating in the country today. And the caricature of Haitians as a people inherently prone to violence and unable to govern themselves – so frequently cited by the apologists for the American Occupation – is still used today as justification for the prolongation of MINUSTAH’s disastrous presence in Haiti.

If the US remains as entrenched in the management of Haiti’s affairs as it did during the Occupation, it is because that same missionary capitalism – borne of a sense of untapped opportunity, and a White Man’s Burden to develop a people still seen as culturally backward – that was so ebulliently expressed by Senator McCormick in 1920 continues to captivate so many Americans today.

The US quickly organized a ‘popular referendum’ to approve the new constitution, and it was accepted in a sham vote in which less than 5% of the population participated. The restraints were off and Haiti was finally for sale to outside investors.

Aside from the obvious afflictions visited upon a people living under foreign military occupation – routine physical violence, sexual assault, and stifling media censorship to name a few – Haitians suffered countless other indignations during the Occupation.

Bureaucrats were imported from the US to manage Haiti, and their extravagant salaries were paid directly from the Haitian treasury. Meanwhile, Haitian functionaries doing the same work were paid far less. In the countryside, able-bodied Haitian men were rounded up and forced into hard labour, often building roads through land that had been seized from them by the Marines.

Such a heavy-handed occupation could only provoke discontent and uprisings, but the beleaguered and impoverished Haitian masses were ultimately no match for a few thousand heavily-armed American Marines, or for the Gendarmerie, a force composed of both Americans and Haitians that the Occupation used to quell rebellions and put down protests.

Ending the official occupation

Even though the Haitian resistance produced a number of charismatic and quixotic figures, what ultimately brought about the end of US military occupation was not any defeat suffered by the Marines; rather it was their success in crushing the discontented masses with increasingly brutal efficiency.

On December 6, 1929, Marines opened fire on an unarmed crowd of protesters in Les Cayes, killing at least a dozen people. The Cayes Massacre attracted plenty of unfavorable attention from international newspapers, and provoked protests within the US against the Occupation of Haiti.

The Occupation had become increasingly unpopular, but it was also becoming less profitable: the Great Depression and the collapse of commodity markets had caused a steep fall in the price of coffee, which was the Haitian economy’s principal export.

Faced with diminishing returns, President Herbert Hoover had no enthusiasm for prolonging any further the Occupation that he had inherited, and declared in February of 1930: “The primary question which is to be investigated is when and how we are to withdraw from Haiti. The second question is what we shall do in the meantime.”

Enduring legacy of occupation

Despite the pressure to withdraw, the Occupation force had become so thoroughly embedded in every aspect of Haitian life that it was not easy for the US to extricate itself. The Marines would not leave Haiti until August 15, 1934 and the US would maintain direct control of Haiti’s external finances until 1947. But even then, the Occupation was not really over.

In the years that followed, the Gendarmerie – the American-trained force created during the Occupation – became the principal power broker in Haitian politics. Presidents were imposed and deposed by the Gendarmerie through a series of bloody coups d’états; three of the military strongmen who assumed power during the tumultuous 1950s were graduates of the American Military School in Haiti that had been set up during the Occupation.

Quite evidently, the stated goal of the US Occupation – to bring ‘stability’ to Haiti – had failed spectacularly. In fact, the revolving door of warrior presidents wouldn’t end until 1957 with the rise to power of “President for Life” Francois ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, a brutal dictator who won US support because of his anti-Communist rhetoric.

Yet it seems rather naïve to describe the Occupation of Haiti as a failure for the promotion of US’ interests. Indeed, far from being“America’s least successful experiment in imperialism” as The Guardian described it at the time, the Occupation of Haiti seems to have been one of the most enduring.

The US remains deeply implicated in Haiti’s economy, and still insists on the right to intervene for the benefit of US corporations. In 2009 when the Haitian government passed a measure to raise the country’s meagre minimum wage from 24 cents an hour to 61 cents an hour, several US-based garment manufacturers that have factories in Haiti – including Levi’s, Hanes and Fruit of the Loom – protested to the US embassy in Port-au-Prince. The US Ambassador then pressured René Préval, Haiti’s President at the time, to halt the increase from going into effect. As a result, the Haitian government agreed to limit the minimum wage to 31 cents per hour.

Although such interventions are certainly less dramatic than troops marching on the National Bank, the resulting transfer of wealth from Haitians to US corporations is no less so.

And the US has also continued to maintain multiple levers for manipulating Haitian politics: forming paramilitary groups, intervening to influence elections, and buying support from Haitian politicians (including the current President) through USAID.

Supporters of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who accused the US of deposing him in a coup, protest the US at OAS Summit / Danny Hammontree

It is not difficult to see other echoes of the Occupation’s logic in Haiti today: That expats deserve higher salaries than Haitian staff doing the same work remains an article of faith both for official aid agencies and the many international NGOs operating in the country today. And the caricature of Haitians as a people inherently prone to violence and unable to govern themselves – so frequently cited by the apologists for the American Occupation – is still used today as justification for the prolongation of MINUSTAH’s disastrous presence in Haiti.

If the US remains as entrenched in the management of Haiti’s affairs as it did during the Occupation, it is because that same missionary capitalism – borne of a sense of untapped opportunity, and a White Man’s Burden to develop a people still seen as culturally backward – that was so ebulliently expressed by Senator McCormick in 1920 continues to captivate so many Americans today.

Commentary: When is Guyana's President David Granger going to Africa?

Published on July 21, 2016

By Ray Chickrie

Just last week, Guyana participated in an “oil and gas mentorship programme” in Kampala, Uganda. Guyana which recently discovered a mega oil and gas field off its coast, is making preparation for the development of the country’s oil and gas sector, and this is why Minister of Finance Winston Jordan and Natural Resources Minister Raphael Trotman went to Uganda.

Born in Guyana, Raymond Chickrie was a teacher in the New York City public school system and has also taught in the Middle East

Most likely, the Guyanese delegation needed a visa to enter Uganda, unless there is a visa abolition policy for diplomats between these countries. Guyanese as a whole need visas to travel to Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. On the other hand, Jamaicans and Trinidadians don’t need visas to visit most of these countries.

Interestingly, Guyana, which championed the South Africa and Southern Africa liberation movements at CARICOM, the UN and at the Non-Aligned Movement, hasn’t engaged these countries for the abolition of visas for their respective citizens. Relationship grew cold in the 1990s after the Peoples National Congress party left office.

More disturbing, Guyana does not have diplomatic relationship with over 20 African countries, despite that it is the fastest growing continent today. East Africa most certainly isn’t the basket case economies when President Granger’s PNC party was in power.

Guyana was visited by leaders from Tanzania, Botswana and Zambia. This attests to the strong ties between these countries. As well, the late president of Guyana, Forbes Burnham, visited many African countries. A great deal of this history, Guyana and Africa, has been documented by historian and current president of Guyana, David A. Granger.

President Granger takes pride in this history. It is highly likely that he will renew ties with these countries in Africa and open a diplomatic mission in Addis Ababa, the headquarters of the African Union. “Socially, economically and politically things are happening in Addis… Everyone is in Addis,” remarked one diplomat from a CARICOM country. A mission here will focus on the growing economies of East Africa -- Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania.

Every sitting Indian president of Guyana from 1992 to 2015 visited their ancestral motherland, India. They included Dr Cheddi Jagan, Bharrat Jagdeo and Donald Ramotar. Will President Granger, who penned a paper titled “Forbes Burnham and the Liberation of Southern Africa”, expand Guyana/Africa ties? Will he visit the growing economies of East Africa, Uganda, Kenya or Tanzania?

Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India, last week concluded a visit to Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. China also has been digging deep to exploit Africa’s abundant natural resources.

Strangely, since taking office just over a year ago, no one from the ruling APNU, the former PNC party, has travelled to Dodoma, the capital of Tanzania. Tanzania under the leadership of Baba-W-Taifa (Father of the nation), Dr Julius Nyerere, inspired the PNC government of Guyana for decades, and now they are back in power looking at a vastly different Tanzania. Dr Nyerere visited Guyana twice. Thus, Tanzania may be high on Granger’s list of countries to visit.

Rapidly developing Tanzania today has an investor friendly president, John Magufuli, who is receiving global praises for his battle against corruption. Magufuli is also called the “Bulldozer”, and is known for firing public servants and heads of government agencies during on the spot secret visits. He cancelled Christmas and independence celebrations and used the money to put beds in hospitals. Mr Magufuli is a great example for our Guyanese leaders to follow.

When is President Granger going to Africa? He will be proud to see the strides the continent is making, especially in the fields of economics and national cohesion. East African economies are growing at an average of seven percent yearly. President David Granger and his Foreign Minister Carl Greenidge should forge stronger times with the growing and prosperous economies of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda.

Commentary: When is Guyana's President David Granger going to Africa?

Published on July 21, 2016

By Ray Chickrie

Just last week, Guyana participated in an “oil and gas mentorship programme” in Kampala, Uganda. Guyana which recently discovered a mega oil and gas field off its coast, is making preparation for the development of the country’s oil and gas sector, and this is why Minister of Finance Winston Jordan and Natural Resources Minister Raphael Trotman went to Uganda.

Born in Guyana, Raymond Chickrie was a teacher in the New York City public school system and has also taught in the Middle East

Most likely, the Guyanese delegation needed a visa to enter Uganda, unless there is a visa abolition policy for diplomats between these countries. Guyanese as a whole need visas to travel to Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. On the other hand, Jamaicans and Trinidadians don’t need visas to visit most of these countries.

Interestingly, Guyana, which championed the South Africa and Southern Africa liberation movements at CARICOM, the UN and at the Non-Aligned Movement, hasn’t engaged these countries for the abolition of visas for their respective citizens. Relationship grew cold in the 1990s after the Peoples National Congress party left office.

More disturbing, Guyana does not have diplomatic relationship with over 20 African countries, despite that it is the fastest growing continent today. East Africa most certainly isn’t the basket case economies when President Granger’s PNC party was in power.

Guyana was visited by leaders from Tanzania, Botswana and Zambia. This attests to the strong ties between these countries. As well, the late president of Guyana, Forbes Burnham, visited many African countries. A great deal of this history, Guyana and Africa, has been documented by historian and current president of Guyana, David A. Granger.

President Granger takes pride in this history. It is highly likely that he will renew ties with these countries in Africa and open a diplomatic mission in Addis Ababa, the headquarters of the African Union. “Socially, economically and politically things are happening in Addis… Everyone is in Addis,” remarked one diplomat from a CARICOM country. A mission here will focus on the growing economies of East Africa -- Ethiopia, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania.

Every sitting Indian president of Guyana from 1992 to 2015 visited their ancestral motherland, India. They included Dr Cheddi Jagan, Bharrat Jagdeo and Donald Ramotar. Will President Granger, who penned a paper titled “Forbes Burnham and the Liberation of Southern Africa”, expand Guyana/Africa ties? Will he visit the growing economies of East Africa, Uganda, Kenya or Tanzania?

Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India, last week concluded a visit to Mozambique, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. China also has been digging deep to exploit Africa’s abundant natural resources.

Strangely, since taking office just over a year ago, no one from the ruling APNU, the former PNC party, has travelled to Dodoma, the capital of Tanzania. Tanzania under the leadership of Baba-W-Taifa (Father of the nation), Dr Julius Nyerere, inspired the PNC government of Guyana for decades, and now they are back in power looking at a vastly different Tanzania. Dr Nyerere visited Guyana twice. Thus, Tanzania may be high on Granger’s list of countries to visit.

Rapidly developing Tanzania today has an investor friendly president, John Magufuli, who is receiving global praises for his battle against corruption. Magufuli is also called the “Bulldozer”, and is known for firing public servants and heads of government agencies during on the spot secret visits. He cancelled Christmas and independence celebrations and used the money to put beds in hospitals. Mr Magufuli is a great example for our Guyanese leaders to follow.

When is President Granger going to Africa? He will be proud to see the strides the continent is making, especially in the fields of economics and national cohesion. East African economies are growing at an average of seven percent yearly. President David Granger and his Foreign Minister Carl Greenidge should forge stronger times with the growing and prosperous economies of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda.

Commentary: When is Guyana's President David Granger going to Africa?

Last edited:

Kyle C. Barker

Migos VERZUZ Mahalia Jackson

Subs

Puff & Stuff: How Afro-Cuban American Twin Sisters Are Shaking Up The Cigar Business

July 20, 2016 ‐ By Ann Brown

Yvette and Yvonne Rodriguez

The cigar industry is dominated by older white males. So imagine the shock of cigar store owners in Miami when Afro-Cuban twin sisters Yvonne and Yvette Rodriguez come rolling in with personalities as big as their Afros to promote their own line of Cuban cigars, Tres Lindas Cubanas Cigars. Just in case you haven’t heard, it’s the only cigar company owned and operated by Black women.

And the Rodriguez sisters plan to take more than just a puff from the cigar industry; they want to be major players. After all, it is a growing industry. According to the CDC, about 13 billion cigars, including 12.4 billion large cigars and cigarillos and 0.6 billion little cigars, were sold in the United States in 2014.

Yvonne and Yvette are cigar aficionados themselves. Growing up seeing their grandmother smoke Cuban stogies, they had no hesitation in lighting up themselves. Not only do the sisters love a good smoke, they love their Cuban heritage and their Afro-Cuban roots. Raised in a mixed-race immigrant family, the twins’ mother was a Cuban mulata, and their father, a Black Cuban who fled Cuba to live in the Miami. All of this is reflected in their cigar brand. Launched two years ago, Tres Lindas Cubanas Cigars represents the diversity the country. They have three signature cigars: “La Clarita,” which means fair-skinned and the cigar itself is light-medium bodied;“La Mulata,” which translates to a mixture of black/white and the cigar is medium-full and “La Negrita,” which means black woman, but for the cigar it’s their strongest, full-bodied option.

The is actually no true Cuban cigar for purchase in America, due to the embargo the United States still has against Cuba despite warming relations. Most of the cigars labeled Cuban on the American market are growing in countries like Nicaragua using a Cuban seed. The same goes for Tres Lindas.

There are actually four partners in Tres Lindas–the sisters and their boyfriends–Jamil Raheem, who handles Sales and the company’s cigar blends as well as hosts Cigar Happy Hours with Cigar Society of South Florida and Marcus Lightfoot, head of operations. Yvette oversees all of the company’s Media & Public Relations because, as the company’s website says “she looks good on TV,” and Yvonne handles Digital Media as “she is hell-bent on taking long lunches and attending art exhibits all while managing a fast-growing Cigar brand.”

Tres Lindas Cubanas cigars are sold in select shops in Miami and online. We got to chat with the Rodriguez sisters and we found they are truly the type of gals you’d like to hang out with at a cigar lounge puffing on a La Negrita.

MadaemNoire (MN): You are actually running two business, a PR firm and the cigar company. How do you juggle both.

Yvette: We’ve been working in public relations for over six years. And Yvonne and I started the cigar business in 2013. It took us a year to develop our blend. We started selling our cigars in 2014. We juggle it because they work together. We do our own PR for the cigar business and we treat Tres Lindas as a client of the PR business. Since we are small, we use all the resources we already have and it’s worked out great.

MN: Do you both smoke cigars?

Yvonne: It used to be taboo for women to smoke but we grew up in a household were the women enjoyed smoking cigars, especially our grandmother. We idolized our grandmother; whatever she did we wanted to do. She was this very strong woman.

Also we were fascinated by our Cuban roots. We were born in the United Sates, so we’re basically African American. But loved our Afro-Cuban roots–cigar smoking, Cuban coffee, the music, playing dominos. We got to visit Cuban a few years ago and it changed our lives; we wanted to fully embrace our Afro-Cuban roots.

MN: How do you grow the cigars?

Yvette: Since there is technically still an embargo, there are no true Cuban cigars in the U.S. Most people grow their cigars in countries like Nicaragua, which has a climate similar to Cuba. Our cigars come from Cuban seed and we deal with growers in Nicaragua.

MN: It seems like a very complex process?

Yvonne: It’s a business like any other business. As far as production we have a lot of connections with people who own land in Nicaragua. Finding the right cigar blend, it’s like developing a wine. It’s all a matter of taste.

MN: What have been some of the challenges?

Yvette: We are very new and we still have challenges, starting with the fact we don’t come from a tobacco farm family. Many of the cigar brands come from people who grew up in tobacco farm family. It is also a challenge dealing with the major brands. But I think we have a plus because we came from the consumer side, we know what we like to smoke and what others like to smoke.

MN: Since you are the only cigar brand owned by women, and Black women at that, is that a challenge?

Yvonne: There are actually a lot of women in the industry–like the cigar rollers. And there may be some women who have taken over the family business, but we, as far as we can figure out, are the only women who started our own cigar brand, and the only Black women to do so. And some of the other people in the industry don’t know what to make of us. We act as our own sales reps and we come rolling into the cigars stores to sell our line and we come in with our Afros and big personalities. We stand out. We stand out like aliens. But that’s a good thing–’cause we always make a lasting impression.

One the downside, the stores put up a lot of road blocks. When we walk into a shop and we are trying to sell our cigars, the shops are asking us all the basics like we don’t know anything–and this is an everyday thing we go through. But of course we have all the answers and we surprise them. I like that we are a surprise.

MN: This is a family business and your boyfriends are also your partners, how does that work?

Yvette: Actually it works out great. We each have a specialty and we use this as a strength, especially since we are grassroots. We keep it professional when we are doing business. Plus, we all love smoking cigars. If we didn’t have the business we’d still be in a cigar lounge, talking, relaxing, and enjoying a good smoke. So as a business we get to do what we all love together.

Yvonne: We have been creative in getting the word out and using all of our resources. We have even started aYouTube channel to show the behind the scenes of our business our brand and the cigar lifestyle. It’s fun!

MN: Smoking cigarettes can be hazardous to your health. How about cigars?

Yvonne: Yes, and we don’t advocate smoking all the time, though cigar smoking is a little better because you don’t inhale and it takes a least an hour to smoke. Since it takes longer, people usually smoke in the company of others and are socializing. And even though I love smoking a good cigar, I don’t do it all of the time. With cigars, it’s more of a culture. You have people who are cigar aficionados, people who collect cigars. Its like wine drinkers, people who love wine. And like anything you do it in moderation.

Yvette: There are of course some health concerns, but cigar smoking is different. We actually we went to Washington last year because the FDA wants to eliminate all tobacco production. So we went to lobby and to speak to congressmen. Cigars don’t have additives and it’s a natural product, so it’s not addictive. Cigar smoking is more of a hobby.

MN: Are you targeting women with your cigar brand?

Yvonne: Not particularly. Cigars are unisex. And many women in Miami grew up with women smoking cigars, it’s part of the Cuban culture.

MN: What do you like the most about being cigar entrepreneurs?

Yvette: I am so proud of how we have developed our brand and mission. We didn’t have a template and it still worked.

Yvonne: We wanted our bland to reflect who we are–and we are Black women, we are Cuban women. And I think our products reflect this and honors all Cuban women–that we come in all shapes, colors, ¡and sizes. Our company is a homage to our ancestors and a celebration of the Afro-Cuban woman.

July 20, 2016 ‐ By Ann Brown

Yvette and Yvonne Rodriguez

The cigar industry is dominated by older white males. So imagine the shock of cigar store owners in Miami when Afro-Cuban twin sisters Yvonne and Yvette Rodriguez come rolling in with personalities as big as their Afros to promote their own line of Cuban cigars, Tres Lindas Cubanas Cigars. Just in case you haven’t heard, it’s the only cigar company owned and operated by Black women.

And the Rodriguez sisters plan to take more than just a puff from the cigar industry; they want to be major players. After all, it is a growing industry. According to the CDC, about 13 billion cigars, including 12.4 billion large cigars and cigarillos and 0.6 billion little cigars, were sold in the United States in 2014.

Yvonne and Yvette are cigar aficionados themselves. Growing up seeing their grandmother smoke Cuban stogies, they had no hesitation in lighting up themselves. Not only do the sisters love a good smoke, they love their Cuban heritage and their Afro-Cuban roots. Raised in a mixed-race immigrant family, the twins’ mother was a Cuban mulata, and their father, a Black Cuban who fled Cuba to live in the Miami. All of this is reflected in their cigar brand. Launched two years ago, Tres Lindas Cubanas Cigars represents the diversity the country. They have three signature cigars: “La Clarita,” which means fair-skinned and the cigar itself is light-medium bodied;“La Mulata,” which translates to a mixture of black/white and the cigar is medium-full and “La Negrita,” which means black woman, but for the cigar it’s their strongest, full-bodied option.

The is actually no true Cuban cigar for purchase in America, due to the embargo the United States still has against Cuba despite warming relations. Most of the cigars labeled Cuban on the American market are growing in countries like Nicaragua using a Cuban seed. The same goes for Tres Lindas.

There are actually four partners in Tres Lindas–the sisters and their boyfriends–Jamil Raheem, who handles Sales and the company’s cigar blends as well as hosts Cigar Happy Hours with Cigar Society of South Florida and Marcus Lightfoot, head of operations. Yvette oversees all of the company’s Media & Public Relations because, as the company’s website says “she looks good on TV,” and Yvonne handles Digital Media as “she is hell-bent on taking long lunches and attending art exhibits all while managing a fast-growing Cigar brand.”

Tres Lindas Cubanas cigars are sold in select shops in Miami and online. We got to chat with the Rodriguez sisters and we found they are truly the type of gals you’d like to hang out with at a cigar lounge puffing on a La Negrita.

MadaemNoire (MN): You are actually running two business, a PR firm and the cigar company. How do you juggle both.

Yvette: We’ve been working in public relations for over six years. And Yvonne and I started the cigar business in 2013. It took us a year to develop our blend. We started selling our cigars in 2014. We juggle it because they work together. We do our own PR for the cigar business and we treat Tres Lindas as a client of the PR business. Since we are small, we use all the resources we already have and it’s worked out great.

MN: Do you both smoke cigars?

Yvonne: It used to be taboo for women to smoke but we grew up in a household were the women enjoyed smoking cigars, especially our grandmother. We idolized our grandmother; whatever she did we wanted to do. She was this very strong woman.

Also we were fascinated by our Cuban roots. We were born in the United Sates, so we’re basically African American. But loved our Afro-Cuban roots–cigar smoking, Cuban coffee, the music, playing dominos. We got to visit Cuban a few years ago and it changed our lives; we wanted to fully embrace our Afro-Cuban roots.

MN: How do you grow the cigars?

Yvette: Since there is technically still an embargo, there are no true Cuban cigars in the U.S. Most people grow their cigars in countries like Nicaragua, which has a climate similar to Cuba. Our cigars come from Cuban seed and we deal with growers in Nicaragua.