Quibdó: the torments of a city held hostage by violence

The capital of Chocó is experiencing its worst days due to the overflowing growth of violence. In certain areas, trade is almost paralyzed and the death of young people is close to historic levels. The X-ray of a city besieged by violence.

May 1, 2021

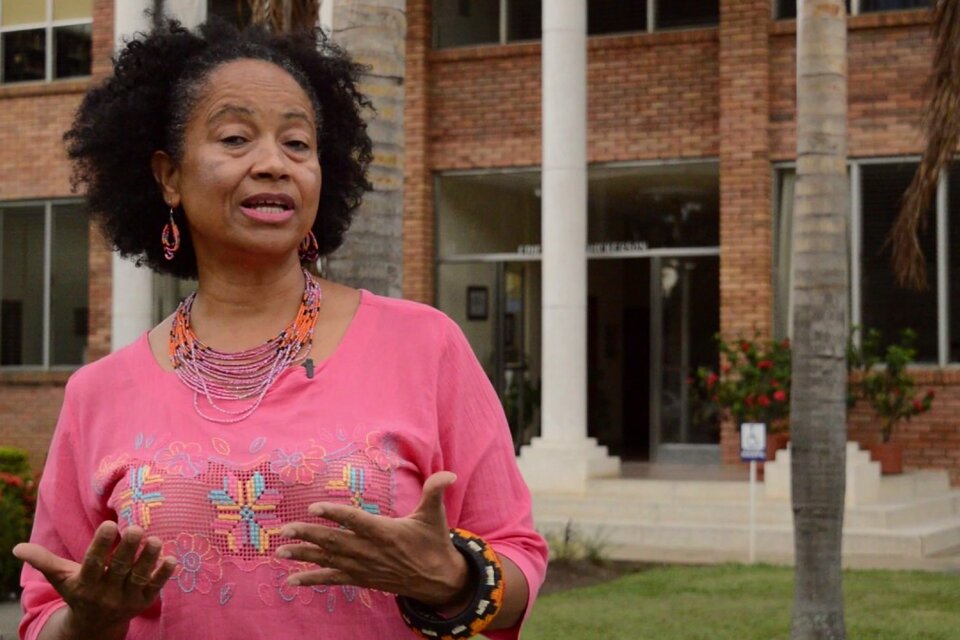

Photo: Saulo Guerrero/Radio Nacional de Colombia

In the first bill — it was actually a poorly written letter with few words — that Gabriel Velasco received, he was given a period of two hours to communicate with the leader of the criminal gang that controls the northern area of Quibdó, Chocó. He was officially informed that his small retail shop was part of the extortion payroll, which is hitting this city hard. Gabriel refused.

Not only did he dismiss the warning, but he threw the paper at the feet of the person who gave it to him: a small, barefoot boy, barely 12 or 13 years old. The next day, three hit men entered his business, determined to kill him.

Gabriel escaped, but his 14-year-old son did not. The gunmen only found the minor, who wanted to take refuge between the black bars of the small establishment, however, it was not enough. Four bullets killed him: two in the chest, one in the left arm and one in the face.

The second message was delivered with blood; no one here challenges those who control the city, and for those who do challenge them, there are only two outcomes: death or exile. Gabriel suffered the death of his son and closed shop; there was no more reason to fight.

The northern area of Quibdó has 23 neighborhoods, mostly invasions of large migrations from other parts of Chocó when the armed conflict raged against the department between 1990 and 2004.

The streets of several areas are still unpaved, there are no aqueducts and no sanitary sewer. Throughout the streets of each neighborhood, only known residents — or whoever has permission from the gang that controls the territory — can walk through. One cannot jump invisible barriers, nor invade, even with half a step, the terrain of others.

This became clear on Wednesday, April 21, when the Loco Yam gang detained, murdered and dismembered three waste picker children in the Los Claveles area, in the Buenos Aires neighborhood, also in the northern zone. The authorities' report says that the three minors — 17, 12 and 11 years old — were engaged in recycling and wanted to enter the neighborhood without permission.

The youth of Quibdó held a protest to demand the authorities to protect the community, which is at the mercy of criminal gangs, who impose themselves with the fear of bullets. Photo: Saulo Guerrero/Radio Nacional de Colombia

They were approached by men known as Ganya, Andresito, Carlos Mario and Járlinson plus six members of the Loco Yam gang, taken to a creek, beaten, attacked with a firearm and then dismembered with machetes. A display of brutality that is just the tip of the iceberg of what happens in Chocó.

The municipal ombudsman, Domingo Ramos, says that what is happening is the product of the incubation of crime for several years. He assures that Quibdó is criminally dominated by the Urabeños, who have several smaller structures at their service, such as the Loco Yam gang; and those who call themselves Mexicanos, who have the patronage of the ELN.

These two macrostructures have divided the city in order to have control over micro-trafficking and, most importantly, have

commercial establishments they can extort a monthly fee, sometimes demanding millions.

No one is safe in Quibdó: not the neighborhood shopkeeper nor multinational companies such as Postobón, which closed shop after several extortion requests, shootings at the front and a robbery of merchandise at the main headquarters in the city center.

“They send a kid your way with a bill and if one does not comply, an intimidation process begins until the owner closes shop or gets killed”, says a member of the Quibdó Merchants Association.

The most recent case of attempted murder of a merchant occurred in the center of the city two days after the murder of the children in Buenos Aires.

A hitman came to a store and tried to assassinate the owner, the bullets grazed the victim's neck and right cheek. He was miraculously saved, other shopkeepers say. Today that store is closed.

According to an estimate by the Quibdó Merchants Association, last year at least 100 stores were closed, being unable to withstand the pressure of extortions. “Here they ask for up to 100 million pesos, what merchant in the middle of a pandemic has that kind of money?”, they say.

In the case of neighborhood stores, many have chosen not to sell any kind of liquor, because that represents losses. In a superior display of power, gang leaders demand that shopkeepers provide them with aguardiente, rum or whiskey whenever they are celebrating. “

Here they send a kid and tell us that such and such told us to send two or three bottles to the pary, and then what do you have to do? You send them to avoid any problems”, says the owner of a small business in the Kennedy neighborhood, in the city center.

Minors as a shield

The minor who delivered the extortion bill to Gabriel was captured two days later. Due to his age there was no prosecution, nor was he obliged to testify to locate the whereabouts of the murderers of Gabriel's son. The case has not advanced much so far.

This is precisely what those who recruit them are looking for: having soldiers who cannot be prosecuted. “

They use these kids as bellmen, also so they can send the extortion bills to the commercial establishments and, on many occasions, they are the ones who shoot at these businesses in order to intimidate and make them pay. Children are their instruments and they call them their soldiers”, says ombundsman Ramos.

Children are active instruments in this new wave of violence in Quibdó. According to the monitoring group Transparencia por Chocó, in the last 18 months more than 157 young people have been murdered in the city.

Among this painful number are the three minors brutally attacked in Buenos Aires. Everything points to the fact that the Loco Yam gang, which controls Buenos Aires, Los Claveles and Las Palmeras, upon seeing them in the area, believed that they were emissaries of other structures that were stepping on their lands. They intimidated them, cut off their legs and hands and then shot them in the middle of a creek that runs through the area. The northern area is one of the most vulnerable in Quibdó, most of the people are internal refugees and work informal jobs. “If they have something for breakfast, they hardly have anything for lunch”, says ombundsman Ramos.

Quibdó has an unemployment rate of over 22%; no other city in Colombia presents such high unemployment figures. “There is a vicious cycle here: the violent ones have businesses in check, businesses close and that generates more unemployment, which generates more violence”, says a citizen observer who asked not to be named.

In the northern zone there are no football fields, nor spaces suited for the leisure of minors. It is a hostile territory, with unpaved streets and alleys that lead to creeks and jungle areas. The meeting point for those who want to share a moment of relaxation is the corner of the block, because in 23 neighborhoods there is not a single park.

Quibdó has a marked urban underdevelopment and a state neglect that has contributed to violence. The authorities have recorded eight criminal structures operating in Quibdó, which were strengthened in the first days of the 2020 quarantine. These groups began to display their authority by declaring zone curfews and the penalty for those who did not comply was death.

Citizens complied in the name of the pandemic. Even some members of the local administration welcomed the authority in the hands of individuals, however, as expected, the monster grew and is now difficult to control. President Iván Duque himself was informed of this situation. He traveled with a delegation in October of last year, walked some streets at night and promised to attack crime so that “tranquility returns to Chocoano homes”. He left the next day and violence continued its course without major setbacks.

The other pandemic

Yajaira Palacios was called two days after her Yamaha Bws II motorcycle was taken. The same thieves who intimidated her with firearms and stripped her of her vehicle demanded three million pesos to return what was stolen. “We don't want this, we just want you to pay to have it back”, they told her.

She did not concede to the extortion for a very simple reason:

why get it back if they could steal it again at any moment? Theft for extortive purposes has become commonplace in Quibdó. Fearful citizens agree to pay to retrieve what was forcibly taken from them. Thieves do not sell what they steal, they renegotiate it with the same owner.

Gang leaders previously study the victim: they know where they live, who they have a relationship with and their

economic status to answer for what they themselves take from them. It is a give-and-take situation: first they act as the perpetrators and then they present themselves as saviors and mediators so that citizens can recover their stolen objects. They create a problem so they can immediately appear with the solution.

Robbery in all its forms has gone through the roof and is a daily occurence in Quibdó: from simple stickups to large operations, such as the robbery of the Postobón headquarters. “Women cannot ride a ‘rappi’ (motorcycle taxi) with their bags on their side, because another motorcycle pulls up and snatch them away. Downtown business owners must attend with a knife between their teeth, because at any given moment a gang of boys might show up and vacate everything”.

The recoil of violence

Quibdó has over 126,000 inhabitants and is surrounded by jungle in the middle of the imposing Atrato River. For years the city was a fortress of the FARC to break the law and transport drugs up to the Urabá region and the Chocoano Pacific. Soon came the paramilitaries and one of the most intense battlefields took place in Chocó.

This rural dispute was transferred to Quibdó, as well as hundreds of displaced people from affected territories such as Bojayá. The city became an epicenter of further violence, increasingly exacerbated by the lack of employment, social intervention and state neglect.

With the departure of the FARC from the area, the ELN arrived, which maintains control of the routes in rural areas, but created the urban cell Mexicanos to take over micro-trafficking and make the war tax official for all businesses. On the other side are the heirs of paramilitarism: the branch gangs of Clan del Golfo, which does exactly the same thing as the Mexicanos in neighborhoods and downtown commerce.

Quibdoseños finance a conflict they have no stake in.

These structures recruit young people in the most vulnerable neighborhoods and send them to train for months in rural areas, then they return to be soldiers of criminality, take care of the territories and murder those who do not pay taxes or any stranger who crosses an invisible border without a compelling justification.

The criminal cocktail in Quibdó has all the components: little law enforcement, no social intervention, state abandonment, a fearful citizenry and unemployment at historic levels, which assures armed groups new soldiers. The city travels along the paths of pain and anguish. There is no peace, because violence found everything it needed to be happy there.

Quibdó: the torments of a city held hostage by violence

:quality(70)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/semana/IUWTHHOSLVG4PCR3ATDV5JYDEI.jpg)

:quality(70)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/semana/XCHSFZ3O2JGLVM6HLIKU4ITZSM.jpg)