You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

2024 U.S. Presidential Election Thread: Donald Trump wins & will return to the White House; GOP wins U.S. Senate & U.S. House

- Thread starter FAH1223

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?

Harris has the right idea on housing

It has to be managed as both a consumer good and as an asset class.

Noahpinion

Harris has the right idea on housing

It has to be managed as both a consumer good and as an asset class.

Noah SmithAug 18, 2024

Photo by Micah Carlson on Unsplash

Kamala Harris recently released a bunch of economic proposals, so I’ll be writing a few more posts about her ideas. I was definitely not a fan of Harris’ idea to outlaw “price gouging” at grocery stores (which, fortunately, she seems to be walking back a bit). But I do like her ideas on housing. And since these ideas have also gotten some flak from various centrist commentators, I thought I should stick up for Harris here and explain why I think her approach is good.

First, this requires explaining why housing policy in America is difficult, and what I think an ideal policy would look like.

Housing policy is incredibly tough in America — and in most other rich countries — because housing has to serve two functions at once. It’s both a consumption good and an investment asset. A house is a place to live, but it’s also something that’s supposed to make you wealthier over time, when its price goes up. These two objectives directly conflict — if owner-occupied housing becomes more affordable, that makes most Americans poorer.

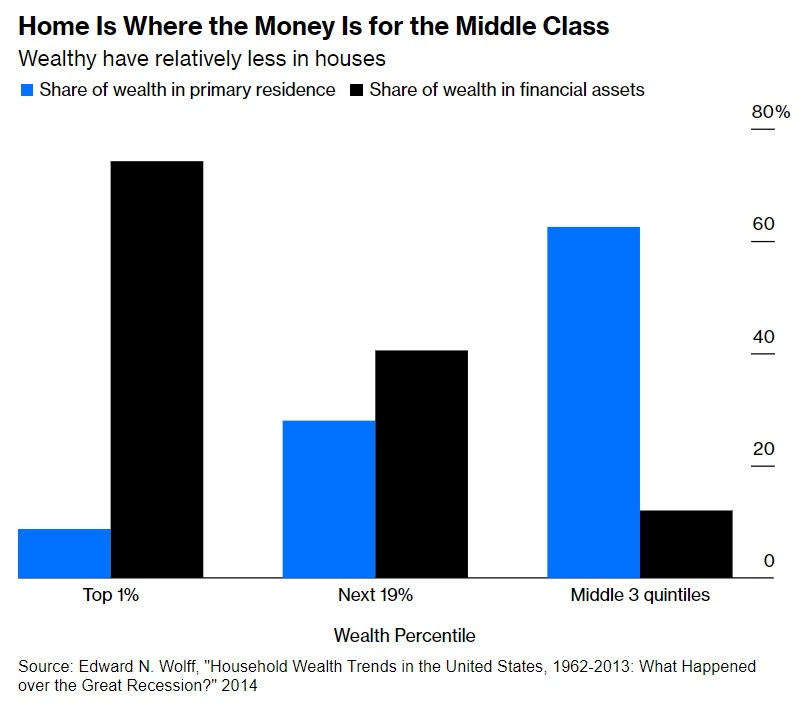

When I say “most Americans”, I’m not exaggerating. The homeownership rate is about two thirds, with only small fluctuations. And for middle-class Americans, most of their wealth is the value of their home:

Source: Noah Smith

This fact sets up a direct and inevitable conflict between two large classes of American society: homebuyers versus homeowners. If you’re buying a house for the first time or looking to significantly upgrade, you want house prices to be as low as possible. But if you already own a home that you’re happy with, you want the price of that home to be as high as possible, so that you can make the homebuyers pay you a lot of money when you’re finally ready to sell. It’s basically a zero-sum game.

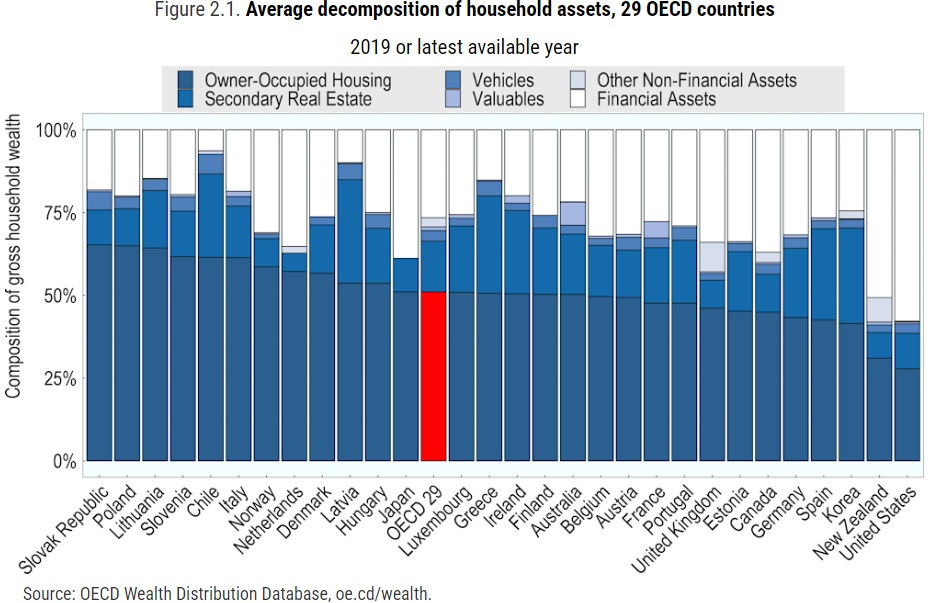

Now at this point, most people say “This is a bad system, it doesn’t have to be this way.” But unfortunately, they’re probably wrong. Lots of people cite Japan as a place where houses depreciate, but this is actually a statistical trick. Japan breaks out the value of housing structures and land separately. The housing structures depreciate, but the land under the houses — which represents 85% of the total value of housing/land in Japan — actually appreciates over time. In fact, Japan has a much higher percent of total household wealth tied up in owner-occupied housing/land than America does. America actually has the lowest percent of wealth in housing out of any OECD country:

Source: OECD

So we’re basically stuck with the homeowner wealth problem — it’s just not going to go away anytime soon. House prices are always going to be a tug of war between homebuyers and homeowners.

Given that inescapable fact, what do you do? A good housing policy needs to make housing abundant without destroying the financial wealth of the middle class. The best policy is one that walks a tightrope between the negative outcomes of “too expensive” and “too cheap”.

As I see it, this means an ideal housing policy has two key characteristics:

It consistently creates a lot of new housing supply, and

It makes housing wealth appreciate slowly but steadily over time, so that people leave the system richer than they bought in.

The second part is really tricky! If house prices go up too fast, people can’t buy in to the system, but if they go up too slow or fall over time, buying in to the system doesn’t yield rewards for the middle class. So the key is slow and steady price appreciation.

The country that probably accomplishes these two goals better than any other is Singapore. In Singapore, the government controls the supply of housing, because it owns about 90% of the land, and can decide how much to build. Singapore’s Housing Development Board increases supply slowly and steadily over time, so that everyone has a place to live, and so that housing — at least, theoretically — earns a modest but predictable financial return.1

In practice it doesn’t always work out that perfectly. In the 90s and 00s, Singaporean housing prices stagnated, and since 2009 they’ve risen a bit too fast, reducing affordability. Housing prices are very hard to control with supply alone, even when the government owns all the land. But in general, Singapore does a great job of ensuring housing abundance while also maintaining very high levels of homeownership (>90%), and predictable financial returns for a wealthy middle class.

Singapore also uses one other strategy to ensure predictable financial returns for homeowners. It gives lower-income first-time homebuyers a government grant to help them buy houses. These grants are currently worth about $61,000 in U.S. dollars, and you have to make less than about $82,000 U.S. in order to qualify for one. Some second-time homebuyers also qualify for a smaller grant.

This is a form of wealth redistribution. It means that as long as lower-income people buy into the housing system, they basically get a free $61,000, since the price of their house on the secondary market is the same as if they had paid full price for it. Obviously this grant comes out of government funds, which ultimately come from Singaporean taxpayers. So it is a redistribution of wealth from richer Singaporeans to poorer Singaporeans, and also from older Singaporeans to younger Singaporeans.

What does that redistribution accomplish? Well, it reduces inequality and keeps the population happier. It also gives lower-income people some property ownership, which means they have a stake in the economic system. And it creates the feeling of upward mobility, because by the time the people who got the first-time homebuyer grant are ready to sell their house, it’s worth a lot more than what they paid for it, even if the market price hasn’t gone up much.

There’s a cost to this redistribution too — not just the cost of taxation, but also the fact that subsidizing lower-income first-time homebuyers tends to push up property prices for everyone else. Singapore handles this by increasing supply to compensate.

Obviously, there are some key aspects of the Singaporean housing system that America can’t copy — our government doesn’t own most of the urban land, like in Singapore. But I think there’s a lot we can do to approximate the Singaporean system, or at least move in its general direction. The key “Singaporean-style” approaches would be:

And this is exactly what Kamala Harris’ housing plan does.

Here are the key elements of Harris’ housing plan:

Points 1-2 of these are credits to first-time homebuyers. Points 4-6 are supply expansion, with Point 6 — the use of federal land for housing construction — looking very Singaporean. Point 3 is a combination of both. (Points 7-8 are other, generally unrelated antimonopoly stuff that I think is probably fine.)

Importantly, increasing the housing supply is central to Harris’ plan. It’s certainly central to her messaging:

Biden’s rhetoric has been very similar:

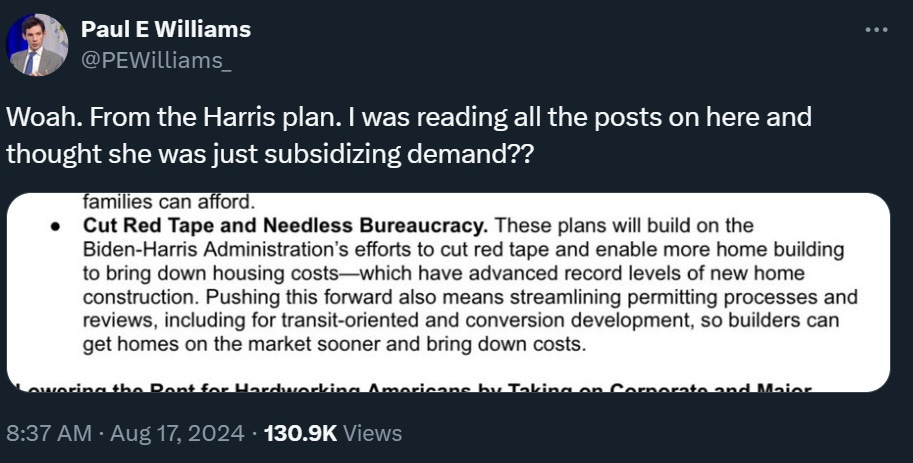

Critics like to say that progressive policy is all about “subsidizing demand while restricting supply”. In this case, though, that criticism doesn’t apply. Harris has tons of ideas for increasing supply, some of which involve activist government, others of which involve deregulation:

In fact, Harris’ plan comes on top of a bunch of other Biden administration initiatives to increase housing supply, mostly using deregulatory approaches. I wrote about Biden’s moves in my roundup yesterday, but I’ll just quote some of the excerpts from that plan again here:

In other words, the Harris economic program — and the Biden program — are solidly in line with the YIMBY movement that has been winning victories at the state level. The key to the YIMBY movement is that it emphasizes goals over methods — the idea is to build housing by any means necessary, including deregulation, tax incentives, and government housing construction all at once. Harris’ plan embodies this all-of-the-above approach.

Critics have lambasted Harris’ first-time homebuyer grants as just another demand subsidy that will push up prices. But Singapore does the same thing! And research suggests that the effect on prices won’t be that huge. This is from Berger, Turner, and Zwick (2020):

A small price increase like that — the grant was about 1/4 the size of the one Harris is proposing — seems like a very small price to pay to help lower-income Americans and younger Americans climb onto the ladder of housing wealth. And the subsidy will be paired with efforts to increase supply. Also, remember that the modest price increase from the first-time homebuyer grants will flow into the pockets of America’s middle-class homeowning majority.

So basically, I’m not worried about that.

Harris’ YIMBY plan won’t fix all that’s wrong with housing in America. Our state and local laws are too fragmented, and our NIMBYs too entrenched, for any federal plan to make the housing shortage go away. But making the U.S. just a little bit more like Singapore can only be a good thing, and that’s what Harris is trying to do here.

Technically, what Singaporeans own is not the land under their houses, but a 99-year lease on their living spaces. The 99-year lease thing is actually a flaw in the system, since it causes a disruption when the lease runs out, kind of like an expiring option. It would be better to just have permanent titles to the living spaces, but restrictions on passing these down via inheritance. In any case, a lot of people refer to ownership of these 99-year leases as “homeownership”, so I will too. It’s basically like condominium ownership in the United States.

Obviously, there are some key aspects of the Singaporean housing system that America can’t copy — our government doesn’t own most of the urban land, like in Singapore. But I think there’s a lot we can do to approximate the Singaporean system, or at least move in its general direction. The key “Singaporean-style” approaches would be:

Have government increase the supply of housing, through deregulation, construction incentives for cities and private companies, and government housing construction

Give credits to first-time low-income homebuyers

And this is exactly what Kamala Harris’ housing plan does.

Here are the key elements of Harris’ housing plan:

- Up to $25,000 in down-payment support for first-time homebuyers.

- To provide a $10,000 tax credit for first-time homebuyers.

- Tax incentives for builders that build starter homes sold to first-time buyers.

- An expansion of a tax incentive for building affordable rental housing.

- A new $40 billion innovation fund to spur innovative housing construction.

- To repurpose some federal land for affordable housing.

- A ban on algorithm-driven price-setting tools for landlords to set rents.

- To remove tax benefits for investors who buy large numbers of single-family rental homes.

Points 1-2 of these are credits to first-time homebuyers. Points 4-6 are supply expansion, with Point 6 — the use of federal land for housing construction — looking very Singaporean. Point 3 is a combination of both. (Points 7-8 are other, generally unrelated antimonopoly stuff that I think is probably fine.)

Importantly, increasing the housing supply is central to Harris’ plan. It’s certainly central to her messaging:

Biden’s rhetoric has been very similar:

Critics like to say that progressive policy is all about “subsidizing demand while restricting supply”. In this case, though, that criticism doesn’t apply. Harris has tons of ideas for increasing supply, some of which involve activist government, others of which involve deregulation:

In fact, Harris’ plan comes on top of a bunch of other Biden administration initiatives to increase housing supply, mostly using deregulatory approaches. I wrote about Biden’s moves in my roundup yesterday, but I’ll just quote some of the excerpts from that plan again here:

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is announcing the availability of $100 million…to communities to identify and remove barriers to affordable housing production and preservation…

The Department of the Treasury and HUD are announcing a major improvement to the Federal Financing Bank (FFB) Multifamily Risk Sharing Program that would provide greater interest rate predictability for state and local housing finance agencies…

Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) and Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) loans used for conversion projects may be eligible for a categorical exclusion under…NEPA…

The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) proposed a new tool that would accelerate historic preservation reviews for millions of federally-funded, licensed, or owned housing units…

HUD anticipates finalizing a rule to update its Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards…[T]he new rule, if finalized, would enable duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes to be built under the HUD Code for the first time…

The Council of Economic Advisers analyzed the importance of state and local government actions to permit and approve new developments more quickly, including examples from HUD’s PRO Housing grants…Reforms to streamline permitting processes can lead to more housing being built more quickly, which will lower housing costs.

In other words, the Harris economic program — and the Biden program — are solidly in line with the YIMBY movement that has been winning victories at the state level. The key to the YIMBY movement is that it emphasizes goals over methods — the idea is to build housing by any means necessary, including deregulation, tax incentives, and government housing construction all at once. Harris’ plan embodies this all-of-the-above approach.

Critics have lambasted Harris’ first-time homebuyer grants as just another demand subsidy that will push up prices. But Singapore does the same thing! And research suggests that the effect on prices won’t be that huge. This is from Berger, Turner, and Zwick (2020):

Using difference-indifferences and regression kink research designs, we find that the First-Time Homebuyer Credit increased home sales by 490,000 (9.8%), median home prices by $2,400 (1.1%) per standard deviation increase in program exposure, and the transition rate into homeownership by 53%. The policy response did not reverse immediately. Instead, demand comes from several years in the future: induced buyers were three years younger in 2009 than typical first-time buyers. The program’s market-stabilizing benefits likely exceeded its direct stimulus effects.

A small price increase like that — the grant was about 1/4 the size of the one Harris is proposing — seems like a very small price to pay to help lower-income Americans and younger Americans climb onto the ladder of housing wealth. And the subsidy will be paired with efforts to increase supply. Also, remember that the modest price increase from the first-time homebuyer grants will flow into the pockets of America’s middle-class homeowning majority.

So basically, I’m not worried about that.

Harris’ YIMBY plan won’t fix all that’s wrong with housing in America. Our state and local laws are too fragmented, and our NIMBYs too entrenched, for any federal plan to make the housing shortage go away. But making the U.S. just a little bit more like Singapore can only be a good thing, and that’s what Harris is trying to do here.

Technically, what Singaporeans own is not the land under their houses, but a 99-year lease on their living spaces. The 99-year lease thing is actually a flaw in the system, since it causes a disruption when the lease runs out, kind of like an expiring option. It would be better to just have permanent titles to the living spaces, but restrictions on passing these down via inheritance. In any case, a lot of people refer to ownership of these 99-year leases as “homeownership”, so I will too. It’s basically like condominium ownership in the United States.

Makes sense that Kamala and Walz are doing great by ignoring the Dems campaign team and doing the opposite of their advice

It’s a miracle that the Dems ever win with how bad their campaign teams are

Let’s be real…DNC is still the party of the Macarena. Choosing to ignore said croney fukkheads that hijacked the 2016 and 2020

Dems primary is certainly worth the risk

mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

This homey’s theme songWhat if I told y’all Texas going blue?

2012 Obama lost it by 16pt

2016 Clinton lost it by 9pts

2020 Biden lost it by 5pts

You see a pattern here? I won’t hold you tho, listen to @FAH1223 don’t listen to me

OmegaK2099

Gettin' It In

What is Charleston Whites deal when he says "slavery was good for black people" on why Kamala Harris shouldn't be president?

mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

This is not nice. What is wrong with the Dems and you weirdos supporting this?Kizinger is going to speak at the DNC. Nice

mastermind

Rest In Power Kobe

The truth about Texas is it has one of the lowest voter participation rates in the US.Yeah, Texas is still just out of reach for Democrats.

Texas Latinos are the second-most conservative Latinos in the country after Florida Latinos. In 2020, Latinos in South Texas shifted right by a big margin.

Also, the rural areas of Texas vote 80–95% Republican, and the big cities of Texas are not blue enough to override the rural voters... yet.

But Kamala isn’t the one to excite people to vote.

Bleed The Freak

Superstar

This guy?

Kanye West ‘told Jewish adidas executive to kiss Hitler portrait daily’

Kanye West ‘told Jewish adidas executive to kiss Hitler portrait daily’

New investigation reveals footwear brand ignored a decade’s worth of West’s allegedly problematic behaviorwww.independent.co.uk

All Fans since Blueprint/College Dropout im sure

iceberg_is_on_fire

Wearing Lions gear when it wasn't cool

Because he is a conservative former military man, former house of representative from Illinois that is going to shyt on Trump for most if not all of his speech and try to convince people that grew up like him to side with the Harris/Walz ticket.This is not nice. What is wrong with the Dems and you weirdos supporting this?

That is beyond nice. We are taking advantage of his desired party's dysfunction.

We need to run up the numbers. This helps that cause.

Mike going to get a Vasectomy?

Mike going to get a Vasectomy?