IllmaticDelta

Veteran

Paul Cuffee

Paul Cuffee or Paul Cuffe (January 17, 1759 – September 7, 1817) was a Quaker businessman, sea captain, patriot, and abolitionist. He was of Aquinnah Wampanoag and Ashanti descent and helped colonize Sierra Leone. Cuffe built a lucrative shipping empire and established the first racially integrated school in Westport, Massachusetts.[1]

A devout Christian, Cuffee often preached and spoke at the Sunday services at the multi-racial Society of Friends meeting house in Westport, Massachusetts.[2] In 1813, he donated most of the money to build a new meeting house. He became involved in the British effort to resettle freed slaves, many of whom had moved from the US to Nova Scotia after the American Revolution, to the fledgling colony of Sierra Leone. Cuffe helped establish The Friendly Society of Sierra Leone, which provided financial support for the colony.

The person who spearheaded “the first, black initiated ‘back to Africa’ effort in U.S. history,” according to the historian Donald R. Wright, was also the first free African American to visit the White House and have an audience with a sitting president. He was Paul Cuffee, a sea captain and an entrepreneur who was perhaps the wealthiest black American of his time.

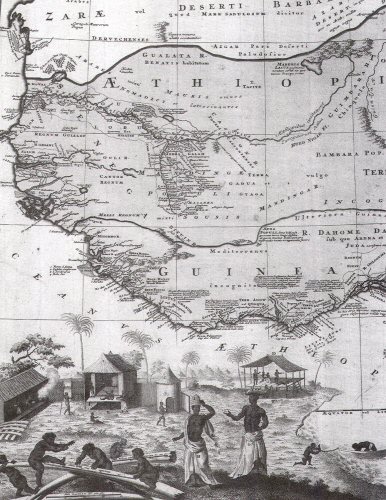

Cuffee was born on Cuttyhunk Island, off Southern Massachusetts, on Jan. 17, 1759, and died on Sept. 7, 1817. He was one of 10 children of a freed slave, a farmer named Kofi Slocum. (“Kofi” is a Twi word for a boy born on Friday, so we know that he was an Ashanti from Ghana.) Kofi Anglicized his name to “Cuffee.”

Paul’s mother was Ruth Moses, a Wampanoag Native American. He ended up marrying a member of the Pequot tribe from Martha’s Vineyard, Alice Pequit.

In 1766, Kofi purchased a 116-acre farm in Dartmouth, Mass., on Buzzard’s Bay, which he left upon his death in 1772 to Paul and his brother, John. When his father died, Paul changed his surname from Slocum to Cuffee, and began what would prove to be an extraordinarily successful life at sea.

Starting as a whaler, then moving into maritime trading, Paul Cuffee eventually “bought and built ships, developing his own maritime enterprise that involved trading the length of the U.S. Atlantic coast, with trips to the Caribbean and Europe,” according to Wright. But he was also politically engaged: In 1780, he, his brother and five black men filed a petition protesting their “having No vote on Influence in the Election with those that tax us,” because they were “Chiefly of the African Extraction,” as his biographer, Lamont Thomas, reports. He was jailed, but got his taxes reduced.

Cuffee’s dream was that free African Americans and freed slaves “could establish a prosperous colony in Africa,” one based on emigration and trade. Cuffee’s visit to the White House happened like this: The U.S. had established an embargo on British goods in 1807, and relations were worsening with Great Britain. On April 19, 1812, U.S. Customs in Westport, Mass., seized Cuffee’s ship and its cargo upon its return from Sierra Leone and Great Britain as being in violation of the embargo. When customs refused to release his property, Cuffee sought redress directly from President James Madison.

On May 2, 1812, he went to the White House, where he met with Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin and with Madison himself, who greeted him warmly and ordered that his goods be returned. Madison queried Cuffee about his recent visits to Sierra Leone, and his ideas about African-American colonization of the new British colony.

The British had founded a settlement there for London’s Committee of the Black Poor; it was called the Province of Freedom in 1787. Then Freetown was founded as a settlement for freed slaves in 1792, the year when the black Loyalists (including George Washington’s former slave, Harry Washington) arrived from Nova Scotia. In 1808, Sierra Leone became a colony.

Cuffee’s dream was that free African Americans and freed slaves “could establish a prosperous colony in Africa,” one based on emigration and trade. As Wright put it, “Cuffee hoped to send at least one vessel each year to Sierra Leone, transporting African-American settlers and goods to the colony and returning with marketable African products.”

Engraving of Paul Cuffee by Mason & Maas, from a drawing by John Pole, M.D. (Library of Congress)

Sierra Leone was already populated in part by former American slaves who had received their freedom by running away from their masters and joining the British as black Loyalists in the Revolutionary War. When the British lost to the Americans, many of these black Loyalists were settled in Nova Scotia. And when conditions there proved too harsh, they had petitioned to be relocated in Sierra Leone.

To distinguish his plan from British and American efforts essentially to use colonization as a way of removing the threat that free African Americans posed to the continuation of slavery, in 1811 Cuffee founded the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone, a cooperative black group intended to encourage “the Black Settlers of Sierra Leone, and the Natives of Africa generally, in the Cultivation of their Soil, by the Sale of their Produce.” He made two trips to the colony that year.

In 1812, after returning from Sierra Leone, Cuffee traveled to Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York to form an African-American version of the British “black poor” organization. Named the “African Institution,” it had self-contained branches in each city, and was charged with mounting a coordinated, black-directed emigration movement.

Cuffee’s close friend, the wealthy sailmaker and inventor James Forten, became the secretary of the Philadelphia African Institution, while Prince Saunders, a well-known teacher and secretary of the African Masonic Lodge in Boston, became the secretary of the Boston African Institution. Cuffee’s movement seemed to be gaining steam among some of the most powerful and wealthy leaders of the free black community throughout the North.

On Dec. 10, 1815, Cuffee made history by transporting 38 African Americans (including 20 children) ranging in age from 6 months to 60 years from the United States to Sierra Leone on his brig, the Traveller, at a cost of $5,000. When they arrived on Feb. 3, 1816, Cuffee’s passengers became the first African Americans who willingly returned to Africa through an African-American initiative.

Cuffee’s dream of a wholesale African-American return to the continent, however, soon lost support from the free African-American community, many of whom had initially expressed support for it. As James Forten sadly reported in a letter to Cuffee dated Jan. 25, 1817, a meeting of several thousand black men had occurred at Richard Allen’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, to discuss the merits of Cuffee’s colonization program and the work of the African Institution. The news was devastating: “Three thousand at least attended, and there was not one soul that was in favor of going to Africa. They think that the slaveholders want to get rid of them so as to make their property more secure.” And then in August, Forten co-authored a statement that declared that “The plan of colonizing is not asked for by us. We renounce and disclaim any connection with it.”

When Paul Cuffee died just a month later, on Sept. 7, 1817, “the dream of a black-led emigration movement,” Dorothy Sterling concludes, “ended with him.” However, the cause of black emigration would be taken up by a succession of black leaders, including Henry Highland Garnet, Bishop James T. Holly, Martin R. Delany, Bishop Henry McNeal Turner and, of course, Marcus Mosiah Garvey.

Some of his descendants