I would say during reconstruction. The thing IS.... Americo-Liberians left VERY VERY VERY early in AA history. They did not go through stuff like Jim-Crow or the Civil Rights movement to say they are 100% AA in ethnicity. IMO its Trauma, History, Slavery, Culture that forms the AA ethnicity imo. Americo-Liberians missed out on most of that. Hell, did Americo-Liberians even have a culture that is very similar to AAs?When did modern AAs form? Was it after the civil war? Or After the civil rights movement?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

American-Liberians=/=African-American

- Thread starter xoxodede

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IllmaticDelta

Veteran

When did modern AAs form? Was it after the civil war? Or After the civil rights movement?

fully materialized, modern afram identity was forged beginning with jim crow era of 1877 + one drop rule of 1910

“Remove Your Shirt.”

In July 1839, my maternal great-great-grandmother Mahala Murchison became the first Negro in Austin, Texas. She was a ten-year-old mixed-race girl from Tennessee. Her father was Kenneth Murchison, her white owner; her mother was a slave whose name and ancestry are lost to history.

In later years, Mahala had six children, three girls and three boys, by white men who lived on neighboring farms. After Emancipation, Mahala’s youngest son, Will, moved away and “passed for white.” Her oldest son, Frank,

Frank Strain

remained in Austin, identified as “colored,” and became a railroad porter. His supervisor ordered him to remove his shirt so that the passengers would know that Frank was a black man, and, therefore, subservient. Frank was, at most, one-fourth black, but to impose social, economic, and political restrictions on people like him, the law applied the One Drop Rule and said he was black.

Definition of The One Drop Rule

The One Drop Rule, an idiosyncrasy of the United States, was based on the notion (and fear) of “invisible blackness.” The rule asserts that any person with even one ancestor of sub-Saharan-African ancestry (one drop of “black” blood) is black. (See video: )

The Antebellum Era

Though Virginia had passed an antimiscegenation law in 1691, which other colonies soon followed, during the years before slavery became entrenched in the South, social and labor conditions were loose among the working class, and many mixed-race babies were born. Their race was a minor consideration. Even after slavery became widespread throughout the colonies, mixed-race children of white mothers were born free. In colonial Virginia, for example, the censuses of 1790 to 1810, revealed that 80 percent of the free African-American families could be traced to of unions between white women and African men. Free people of mixed ancestry who “looked white” were legally absorbed into the white majority. The later conditions of slavery also contributed to the racial admixture. White planters, their sons, overseers, or white neighbors frequently raped black women. Admittedly, some of those relationships were voluntary.

In 1865, soon after the Civil War had ended, Florida passed an act that both outlawed miscegenation and stated “every person who shall have one-eighth or more of Negro blood shall be deemed and held to be a person of color.” Following Reconstruction, to assure “white supremacy,” in part by excluding black citizens from politics and voting, states throughout the south imposed racial segregation and Jim Crow Laws.

The Twentieth century The Jim Crow Laws defined as black anyone with any black ancestry. In 1910, Tennessee adopted a one drop statute. Within the ensuing twenty-one years (in chronological order) Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Virginia, Alabama, Georgia, and Oklahoma followed. During this period, the slave states Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, and the free states Indiana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Utah amended their old “blood fractions” to one-sixteenth or one-thirty-second—the equivalent of one drop.

Before Virginia passed its Racial Integrity Act in 1924, the state legislature had avoided establishing a one drop rule. In 1853, representatives, aware of the ongoing history of interracial relationships, realized that no one could be certain of the “purity” of their whiteness. In 1930, the Census Bureau, yielding to pressure from southern legislators, removed the classification “mulatto.” In all situations in which a person had white and some other racial ancestry, he or she was assigned to that other race.

The One Drop Rule | Who is Black in the U.S.? - The Other Madisons

xoxodede

Superstar

I disagree here. The FPOC are/were Afram's ancestors.....back then you just had scattered Afro-descendents in the USA with regional experiences and cultures but the modern afram is a blend of those 3 traditions/segments on a longer scale of time than when some early stage aframs bounced to Liberia.

Origins of African-American Ethnicity or African-American Ethnic Traits

The newly formed Black Yankee ethnicity of the early 1800s differed from today’s African-American ethnicity. Modern African-American ethnic traits come from a post-bellum blending of three cultural streams: the Black Yankee ethnicity of 1830, the slave traditions of the antebellum South, and the free Creole or Mulatto elite traditions of the lower South. Each of the three sources provided elements of the religious, linguistic, and folkloric traditions found in today’s African-American ethnicity.30

Essays on the U.S. Color Line » Blog Archive » The Color Line Created African-American Ethnicity in the North

The reason I can't fully agree is because out of the 4 million Black people who were in this country in 1860 -- 3,950,528 were enslaved in the South.

After the act abolishing the African Slave Trade in 1807 - the majority of Black people tripled in America -- due to Black people who were already enslaved/born in slavery --- and they were breeded and/or the offspring of the enslaved and they were enslaved and so on.

The majority of those who entered into Liberia were born in the mid to late 1700's and they were indeed descendants of either slaves who were emancipated fairly early -- or the children of white slave masters who had children with their slaves (concubines) and freed them - sometimes setting them up with land and money. The were also not classified as "black" "negro" due to many being "mulatto" or "octaroon."

The vast majority of ancestors of African Americans today come from the Black people who were enslaved in the deep South - states with the highest slave population - which were Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia. The were usually classified as "Negro" or "Black" and they were not freed until emancipation. Even if they were "M" aka Mulatto on the Census in 1860 - they usually were the offspring of rapes due to breeding and just violence by any white man -- from owner to overseer. Not due to being "concubines." And they were still enslaved and married other enslaved people who were listed as "Black."

When they became Freedman/women - the majority of them stayed in the South and yes some did go North - even Canada - but not a significant amount went to Liberia.

In the end, around 13,000 emigrants had sailed to Liberia. -- and most of them were "free people of color" who were from the set of people who were "free people of color" who had never been enslaved or emancipated by their father (white owner) in the late 1700's. Some were the slaves of these people who they emancipated and brought them to Liberia with them -- Most of these people became successful were able to see some benefits such as also owning slaves or good jobs--- and many other things that the Black "Negro" enslaved would never see for years to come -- even after they were emancipated.

Last edited:

xoxodede

Superstar

I would say during reconstruction. The thing IS.... Americo-Liberians left VERY VERY VERY early in AA history. They did not go through stuff like Jim-Crow or the Civil Rights movement to say they are 100% AA in ethnicity. IMO its Trauma, History, Slavery, Culture that forms the AA ethnicity imo. Americo-Liberians missed out on most of that. Hell, did Americo-Liberians even have a culture that is very similar to AAs?

They didn't even go through the Reconstruction Era. Most left before slavery officially ended in 1865 - which was where the majority of Black people in the US were - enslaved. The bulk of the people who went to Liberia went between 1820-1850.

Last edited:

They didn't even go through the Reconstruction Era. Most left before slavery officially ended in 1865 - which was where the majority of Black people in the US were - enslaved. The bulk of them people who went to Liberia went between 1820-1850.

Exactly!

xoxodede

Superstar

might as well drop this because it helps put into context what @xoxodede is trying to get at

repost from me

The Black Yankees (free people of color in the north)

.

.

.

On the interactions between the Black Yankees and Southern Plantation Blacks:

Essays on the U.S. Color Line » Blog Archive » The Color Line Created African-American Ethnicity in the North

.

.

These people were definitely representative of the One-Drop rule.

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817) was a mixed-race, successful Quaker ship owner, and activist descended from Ashanti and Wampanoagparents. He advocated settling freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Cuffee was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa and he gained support from black leaders and members of the U.S. Congress for an emigration plan.[14] In 1815 he financed a trip and the following year,[15] in 1816, Cuffee took 38 American blacks to Freetown, Sierra Leone; other voyages were precluded by his death in 1817. By reaching a large audience with his pro-colonization arguments and practical example, Cuffee laid the groundwork for the American Colonization Society.[16]

Louis Sheridan, farmer, free black merchant, and Liberian official, was probably the Louis Sheridan mentioned in the 1800 will of Joseph R. Gautier (d. 15 May 1807), Elizabethtown merchant, as the son of Nancy Sheridan, "my emancipated black woman" to whom he left "my plantation at the Marsh." Louis obtained a good education and engaged in extensive mercantile operations. Although he was a mulatto with a fair complexion, he was recorded as white in the Bladen County censuses for 1810, 1820, and 1830. He was aided in business by John Owen, former governor, and other white men of the Lower Cape Fear who gave him letters of introduction. Sheridan made business trips to nearby Wilmington as well as to Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere, sometimes making purchases of goods valued in excess of $12,000. As a young man he preached for a brief time and also subscribed to and served as an agent for two black newspapers.

They were not slaves.....

This goes further to showcase "Mulattos" who represented majority of "Free People of Color" did not see themselves as "Black" - hence couldn't be listed as AA.

Source: Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It

thatrapsfan

Superstar

No one is even claiming or arguing that. I don't know how you brought that up.

Point is Americo-Liberians were for the most are not the same as modern day AAs. Especially when people try to say AAs ruined Liberia. Americo-Liberians for the most part were not even enslaved but freed blacks. And so their experience was different from the average AA.

This seems facetious. I find the links in here informative from an educational and historical perspective, but the context behind this thread was that huge African immigrant - AA thread. Check the third post in this thread and OP quotes a poster saying this :

The fact is that the few African-Americans that're in Africa are FAR better guest to Africans than African immigrants are to African-Americans in the US.

So seems the point of this thread was to defend this sentiment.

This seems facetious. I find the links in here informative from an educational and historical perspective, but the context behind this thread was that huge African immigrant - AA thread. Check the third post in this thread and OP quotes a poster saying this :

The fact is that the few African-Americans that're in Africa are FAR better guest to Africans than African immigrants are to African-Americans in the US.

So seems the point of this thread was to defend this sentiment.

Uh... NO. The OP posted that source in the OP in that thread because I ASKED. I saw and then told her to make this thread. Me and @Nemesis already settled that argument peacefully after the thread was locked. So....

- http://www.thecoli.com/threads/we-gotta-have-a-discussion-on-liberia-bruh.494525/

- http://www.thecoli.com/threads/we-gotta-have-a-discussion-on-liberia-bruh.494525/(Everything I have to say has already been said)

- Liberia was born as a neo-colonial nation before there was a term to describe a neo-colonial nation.(Subject to the same foreign entanglements/responsibilities and flaws/failures to locals)

- The "Crime"(ultimate flaw) was believing they got to have there own country cause "Da white man said so" ...not that they despised the Local Africans.

(Excerpt from my thread)

Conclusion:

The simple narrative that African Americans went to Liberia and started shytting on the locals is an over simplified narrative that needs to be cut out. Liberia is a country from the jump has been compromised by Europeans. Be it the Berlin conference, pitting two groups of Africans against each other by telling one you get to have a country in anothers territory, backing multiple coups, being exploited for rubber, etc, etc

Now specifically with the Americo-Liberians(African Americans). The "Crime" was believing they got to have there own country cause "Da white man said so" not that they despised the Local Africans.

1. Local Africans were hampered from electoral access because African Americans wanted their own country.

2. Local African labor was exploited on firestone plants under African Americans for the same reason it was exploited under Samuel Doe, Charles Taylor, and currently under Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

3. Local African labor was exploited in other industries under African Americans for the same reason blood diamond labor was exploited under successive political office holders of Liberia.

4. If African Americans are given Land in Africa it should be by the local population not by outsiders pulling an Israel/Palestine move on Africa.

Like wise these things didn't happen in shashemene because the larger dynamics didn't exist. Emperor haile selassie said here is some land and a political organization to manage it E.W.F. Ethiopian world federation.

Last edited:

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

These people were definitely representative of the One-Drop rule.

Paul Cuffee (1759–1817) was a mixed-race, successful Quaker ship owner, and activist descended from Ashanti and Wampanoagparents. He advocated settling freed American slaves in Africa and gained support from the British government, free black leaders in the United States, and members of Congress to take emigrants to the British colony of Sierra Leone. Cuffee was an early advocate of settling freed blacks in Africa and he gained support from black leaders and members of the U.S. Congress for an emigration plan.[14] In 1815 he financed a trip and the following year,[15] in 1816, Cuffee took 38 American blacks to Freetown, Sierra Leone; other voyages were precluded by his death in 1817. By reaching a large audience with his pro-colonization arguments and practical example, Cuffee laid the groundwork for the American Colonization Society.[16]

Louis Sheridan, farmer, free black merchant, and Liberian official, was probably the Louis Sheridan mentioned in the 1800 will of Joseph R. Gautier (d. 15 May 1807), Elizabethtown merchant, as the son of Nancy Sheridan, "my emancipated black woman" to whom he left "my plantation at the Marsh." Louis obtained a good education and engaged in extensive mercantile operations. Although he was a mulatto with a fair complexion, he was recorded as white in the Bladen County censuses for 1810, 1820, and 1830. He was aided in business by John Owen, former governor, and other white men of the Lower Cape Fear who gave him letters of introduction. Sheridan made business trips to nearby Wilmington as well as to Philadelphia, New York, and elsewhere, sometimes making purchases of goods valued in excess of $12,000. As a young man he preached for a brief time and also subscribed to and served as an agent for two black newspapers.

They were not slaves.....

This goes further to showcase "Mulattos" who represented majority of "Free People of Color" did not see themselves as "Black" - hence couldn't be listed as AA.

Source: Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It

black yankees were the first "One Droppers" (see Fred Douglass story) even before white people made it a rule. The most promiant early advocate/promoters of "black" identity was an afro-european, black yankee from the North

James McCune Smith (April 18, 1813 – November 17, 1865)

was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist, and author. He is the first African American to hold a medical degree and graduated at the top in his class at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. He was the first African American to run a pharmacy in the United States.

In addition to practicing as a doctor for nearly 20 years at the Colored Orphan Asylum in Manhattan, Smith was a public intellectual: he contributed articles to medical journals, participated in learned societies, and wrote numerous essays and articles drawing from his medical and statistical training. He used his training in medicine and statistics to refute common misconceptions about race, intelligence, medicine, and society in general. Invited as a founding member of the New York Statistics Society in 1852, which promoted a new science, he was elected as a member in 1854 of the recently founded American Geographic Society. But, he was never admitted to the American Medical Association or local medical associations.

He has been most well known for his leadership as an abolitionist; a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with Frederick Douglass he helped start the National Council of Colored People in 1853, the first permanent national organization for blacks. Douglass said that Smith was "the single most important influence on his life."[1] Smith was one of the Committee of Thirteen, who organized in 1850 in New York City to resist the newly passed Fugitive Slave Law by aiding fugitive slaves through the Underground Railroad. Other leading abolitionist activists were among his friends and colleagues. From the 1840s, he lectured on race and abolitionism and wrote numerous articles to refute racist ideas about black capacities.

The first African American to receive a medical degree, this invaluable collection brings together the writings of James McCune Smith, one of the foremost intellectuals in antebellum America. The Works of James McCune Smith is one of the first anthologies featuring the works of this illustrious scholar. Perhaps best known for his introduction to Fredrick Douglass's My Bondage and My Freedom, his influence is still found in a number of aspects of modern society and social interactions. And he was considered by many to be a prophet of the twenty-first century. One of the earliest advocates of the use of "black" instead of "colored," McCune Smith treated racial identities as social constructions, arguing that American literature, music, and dance would be shaped and defined by blacks.

The absence of James McCune Smith in the historiographic and critical literature is even more striking. He was a brilliant scholar, writer, and critic, as well as a first rate physician. In 1882 the black leader Alexander Crummell called him "the most learned Negro of his day," and Frederick Douglass considered him the most important black influence in his life (much as he considered Gerrit Smith the most important white one). Douglass was probably correct when, in 1859, he publicly stated: "No man in this country more thoroughly understands the whole struggle between freedom and slavery, than does Dr. Smith, and his heart is as broad as his understanding."

As a prose stylist and original thinker, McCune Smith ranks, at his best, alongside such canonical figures as Emerson and Thoreau. His essays are sophisticated and elegant, his interpretations of American culture are way ahead of his time, and his experimental style and use of dialect anticipates some of the Harlem Renaissance writers of the 1920s. Yet McCune Smith has been completely ignored by literary critics; and aside from one article on him, he has remained absent from the historical record.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

The reason I can't fully agree is because out of the 4 million Black people who were in this country in 1860 -- 3,950,528 were enslaved in the South.

After the act abolishing the African Slave Trade in 1807 - the majority of Black people tripled in America -- due to Black people who were already enslaved/born in slavery --- and they were breeded and/or the offspring of the enslaved and they were enslaved and so on.

The majority of those who entered into Liberia were born in the mid to late 1700's and they were indeed descendants of either slaves who were emancipated fairly early -- or the children of white slave masters who had children with their slaves (concubines) and freed them - sometimes setting them up with land and money. The were also not classified as "black" "negro" due to many being "mulatto" or "octaroon."

The vast majority of ancestors of African Americans today come from the Black people who were enslaved in the deep South - states with the highest slave population - which were Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia. The were usually classified as "Negro" or "Black" and they were not freed until emancipation. Even if they were "M" aka Mulatto on the Census in 1860 - they usually were the offspring of rapes due to breeding and just violence by any white man -- from owner to overseer. Not due to being "concubines." And they were still enslaved and married other enslaved people who were listed as "Black."

When they became Freedman/women - the majority of them stayed in the South and yes some did go North - even Canada - but not a significant amount went to Liberia.

In the end, around 13,000 emigrants had sailed to Liberia. -- and most of them were "free people of color" who were from the set of people who were "free people of color" who had never been enslaved or emancipated by their father (white owner) in the late 1700's. Some were the slaves of these people who they emancipated and brought them to Liberia with them -- Most of these people became successful were able to see some benefits such as also owning slaves or good jobs--- and many other things that the Black "Negro" enslaved would never see for years to come -- even after they were emancipated.

yes but they're intertwined with free people of color lineages

Blair Underwood

I always love when Who Do You Think You Are? features African-Americans because our history is so unique. How did your perspective change when it comes to being Black in America after participating in the show?

Great question. I learned so much doing the show. Everybody has a brick wall they hit when they start doing the linage and history. Most often, when you track African-American history, the census of 1870 is where you hit that brick wall because of slavery. We were able to break that wall three times, which was amazing. I discovered a whole linage of family members who were free people of color in the Virginia south. That was all an education to me. I had a whole line of free people of color in my family, going back to 1790. Their names are documented in the free people of color registers. I never knew that!

Q&A: Blair Underwood Discovers His Roots

Puffy and LL Cool J Discover Free Ancestors Pre-Emancipation in “Finding Your Roots”

In separate experiences, Sean “P. Diddy” Combs and James Todd Smith, also known as LL Cool J, sat across from host Dr. Henry Louis Gates to learn their family trees host record of their ancestors having being freed before the Emancipation of 1863.

While Combs learned his third great-grandparents were living as free African-Americans in Maryland, Smith was learning of his great-great grandparents who lived as free men and women.

Both men’s stories shared similar characteristics such as these: their relatives were inhabitants of “free” states or states where slavery had long worn out its purpose. For Puffy it was Maryland, a state that had seen thousands of slave owners releasing their slaves for both moral and financial reasons.

LL Cool J’s great-grandparents, however, were born into the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania, where slavery had been abolished long ago, revealing that these relatives were born into freedom.

Puffy and LL Cool J Discover Free Ancestors Pre-Emancipation in "Finding Your Roots" | The Source

Finding Your Roots: John Legend and Wanda Sykes

This episode was particularly interesting because it was able to trace their family back to free people of color that were able to break their families from slavery before the civil war and the emancipation of slaves. There were two very interesting stories featured in both families. In John Legend's family there was the story of his ancestor Peyton Polly (This link leads to a book with more details about what happened). Peyton Polly's seven children after having moved to Ohio to escape the slavery they were freed from were stolen in the dead of night by a group of white men who then sold them back into slavery in the states of Virginia and Kentucky. After a series of court battles and testimonies the four children sold back into slavery in Kentucky were released but those in Virginia had to wait until emancipation to be released.

The other story was the story of one of Wanda Sykes' ancestors who was able to gain one branch's family's independence seeing as how she was a white indentured servant. She had an illegitimate child by an African slave and that child was born free. Elizabeth Banks (Wanda's ninth great grandmother), was the woman who "fornicated with a negro slave"giving birth to her eighth great grandmother Mary Banks. Seeing as how her mother was a white indentured servant and not a slave, the status from the mother was passed down to the child granting her freedom.

Towards the end they used DNA analysis again to find the African tribes the guests' mtDNA belongs to, also they were able to find John Legend's y-DNA connection.

John Legend's mtDNA connection to the Mende tribe in Sierra Leone

John Legend's y-DNA connection to the Fula tribe in Guinea-Bissau

Wanda Sykes' mtDNA connection to the Tikar/Fulani tribe in Cameroon

Margarett Cooper's mtDNA connection to the Temne tribe in Sierra Leone

It was really cool again to see this analysis and maybe hopefully one day I'll be able to get it done for the father's mtDNA line which is part of the Haplogroup L from Africa found mainly in Bantu speakers.

http://boricuagenes.blogspot.com/2012/05/finding-your-roots-john-legend-and.html

Wanda Sykes’s Free Ancestors in the 1600s and 1700s | Finding Your Roots

“The bottom line is that Wanda Sykes has the longest continuously documented family tree of any African American we have ever researched.”

The unique thing about Wanda is that she descends from 10 generations of free Virginia mulattos, which is more rare than descendants of mixed-race African-Americans who descend from English royalty.”

Wanda Sykes Traces Roots Back To 17th Century

Last edited:

xoxodede

Superstar

yes but they're intertwined with free people of color lineages

Blair Underwood

Q&A: Blair Underwood Discovers His Roots

Puffy and LL Cool J Discover Free Ancestors Pre-Emancipation in “Finding Your Roots”

Puffy and LL Cool J Discover Free Ancestors Pre-Emancipation in "Finding Your Roots" | The Source

Finding Your Roots: John Legend and Wanda Sykes

http://boricuagenes.blogspot.com/2012/05/finding-your-roots-john-legend-and.html

Wanda Sykes’s Free Ancestors in the 1600s and 1700s | Finding Your Roots

Wanda Sykes Traces Roots Back To 17th Century

I can agree with this. But, they didn't go to Liberia.

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

I can agree with this. But, they didn't go to Liberia.

the people who are actually related to the stocks that went to liberia most likely have distant relatives in Maryland, Virginia and Carolinas

Liberian exodus

The Liberian exodus was a mass emigration of African-American people from the United States, especially South Carolina, to Liberia in 1878.[1]

Interest in emigration had been growing among African-Americans throughout the South since the political campaign of 1876 and the overthrow of the Radical Republican government. Congressman Richard H. Cain called for a million men to leave the injustices they suffered in the United States and leave for Africa. In 1877, the Liberian Exodus Joint Stock Steamship Company was formed in Charleston, South Carolina with a fund of $6,000. Blacks began arriving in January 1878. The company then purchased a bark called the Azor, which arrived in Charleston in March.[1]

On April 21, the Azor set sail with 206 emigrants. A young reporter for the News and Courier, A.B. Williams, accompanied the emigrants all the way to Monrovia and wrote a comprehensive account of the voyage.[1]

Success did come for many of the emigrants who stayed, albeit slowly. By 1880, most had found a livelihood and did not wish to return. By 1890, the Azor passengers were well represented among Liberia's most prominent citizens.[1] Saul Hill, an earlier immigrant from York, South Carolina, established a successful, 700-acre coffee farm. Clement Irons, also of Charleston, built the first steamship constructed in Liberia. The Reverend David Frazier opened a coffee farm with 20,000 trees and was elected to the Liberian Senate in 1891. One passenger, Daniel Frank Tolbert, originally of a town called Ninety-Six in Greenwood County,[2] was the grandfather of President William R. Tolbert, Jr.[3]

I just did a quick search

Tolberts of Liberia.

Believe it or not, there are Tolberts from Liberia (West Africa!) who are descended from the Tolberts of South Carolina ! In 1869 they left the U.S to return to Africa on a ship called the Azor which they had purchased along with several hundred other Black South Carolinians in a group called the Liberian Exodus Movement. Daniel Frank Tolbert age 27 with his wife Sarah and 9 year old son William Richard Tolbert were from a little town called "Ninety Six" in Abbeville County,which is a few miles from Greenwood. Daniel Frank Tolbert left siblings in the U.S. If anyone has information on this branch of the Tolberts or on the Liberian Exodus Movement, I would love to hear about it.Many of the Liberian Tolberts are now back in the U.S and will be holding a family reunion in virginia in July 2000.e-mail Richard Tolbert at

Denise Talbert (View posts)

Posted: 18 Jul 2000 05:08PM

All of my life I've heard stories that some of my father's great-great-uncles went to Liberia and that those brothers who stayed behind changed their name to Talbert. I have a few cousins named Tolbert. My father was from Mississippi. Have your heard a similar story? If so, then we are distant cousins.

Denise

Denise, sorry it took me so long to see your message. I am most definitely interested in hearing more about your family as my great great grandfather Daniel Frank Tolbert left South Carolina in 1878 for Liberia and left sibblings. Any info on your side of the family would be highly appreciated as I am doing a paper on this now. Speak to the oldest living member of your family and get as much detail as possible . Email me at ANGELISTRA@AOL.COM or your can reach me by phone at 914 391 2214 or fax 914 633 7240. Best Richard Tolbert

Kelvinwright167 (View posts)

Posted: 29 Sep 2010 05:14AM

Classification: Query

Hello Mr. Robert Tolbert. I am the grandson of Mr. John Henry Tolbert and son the of Shirley Tolbert Wright. You visited my grandfather several years ago in Greenwood, SC and I remember my uncles telling me about your visit to our family church also. It would be really grey to hear from you as I am possibly planningon travelling to Liberia to work. I can be contacted by email at kelvinwright@gmail.com or calling me at 864-992-9015. Again Thanks

Message Boards

IllmaticDelta

Veteran

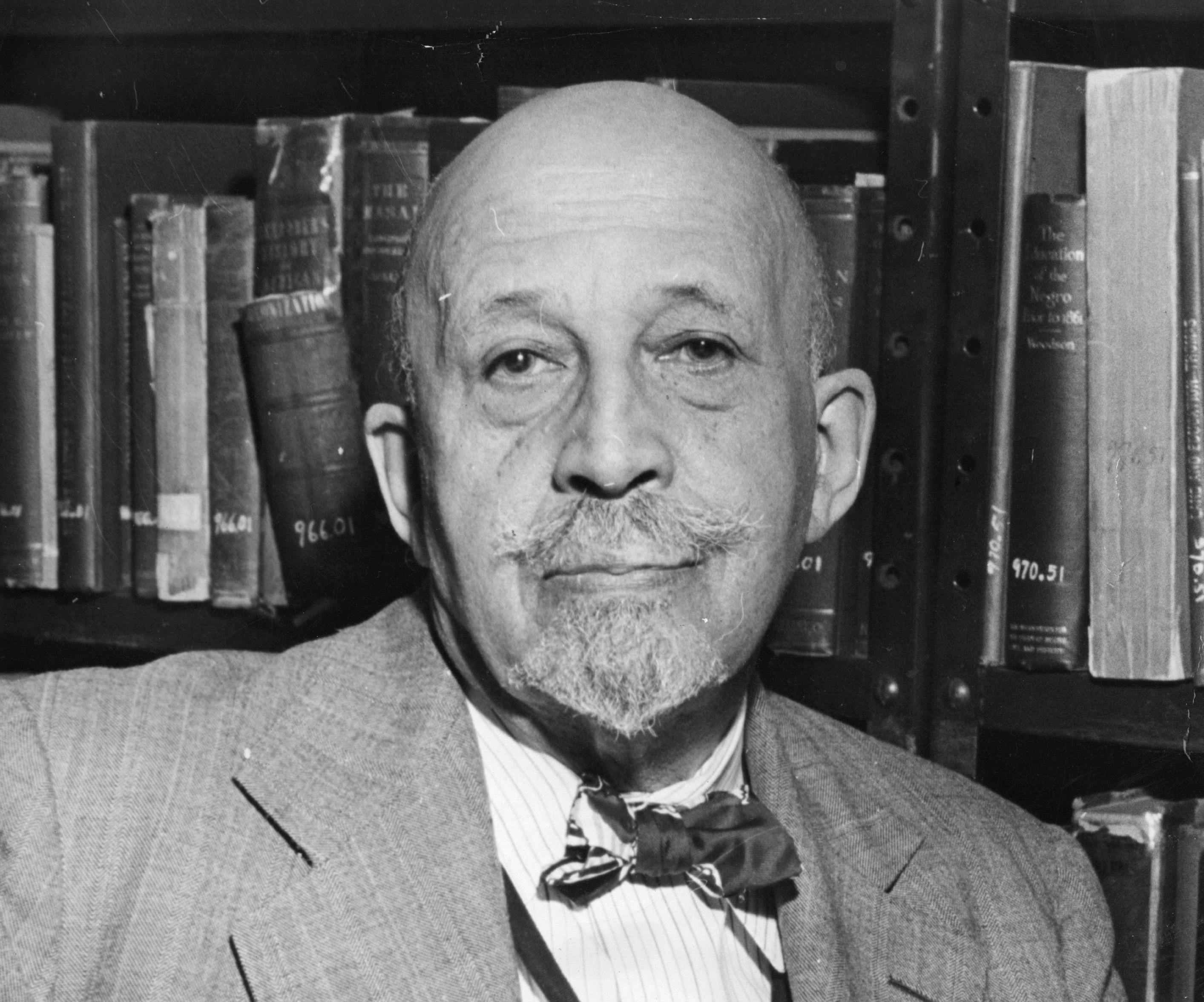

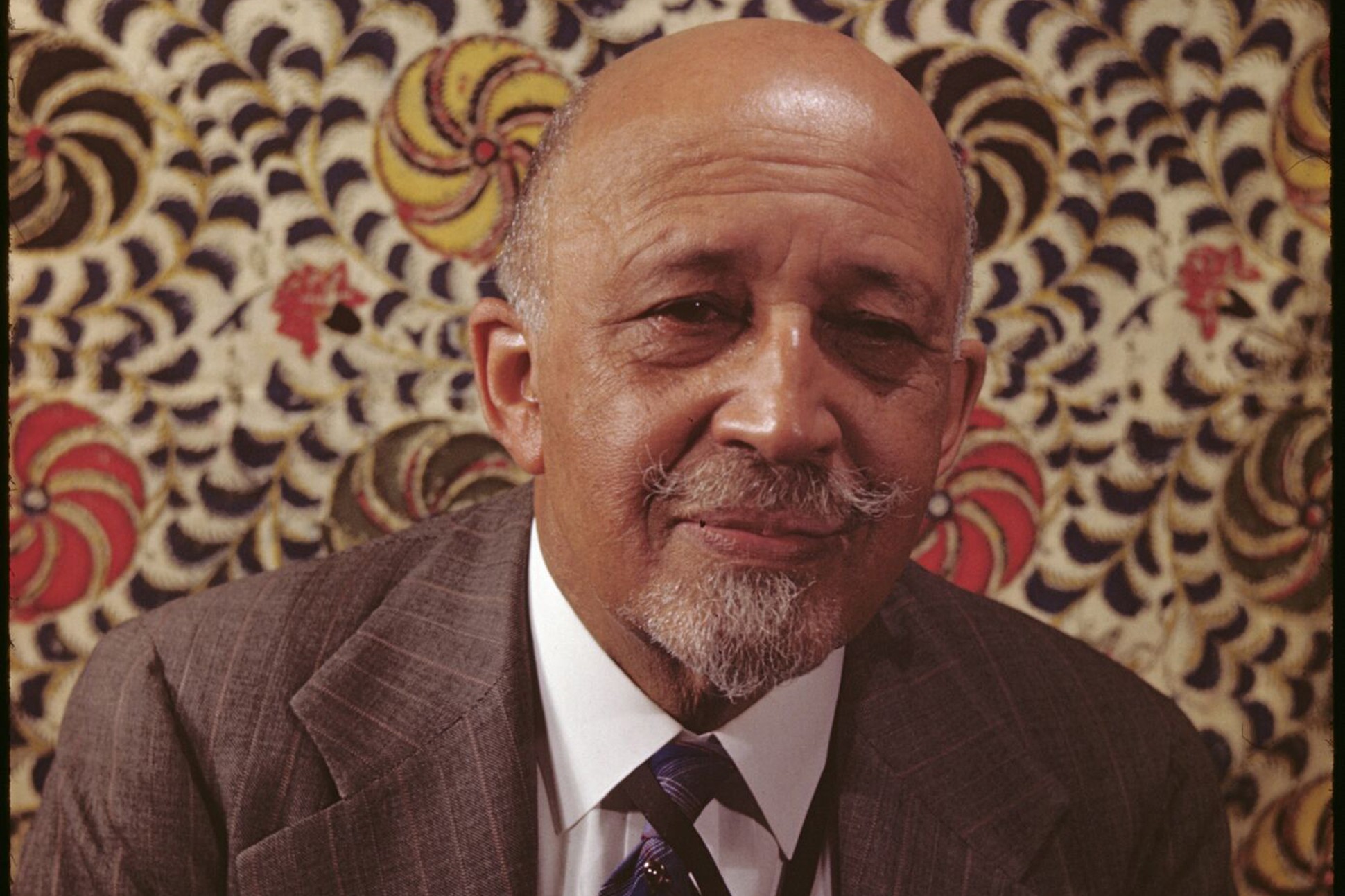

During that time, he had the choice to pass and be white -- but he chose to be Black. I respect it and am grateful.

dubois was undeniably "black" in the Northern context but could have had some wiggle room in the south prior to jim crow/one drop rule era but he would have nener passed for white lol

xoxodede

Superstar

dubois was undeniably "black" in the Northern context but could have had some wiggle room in the south prior to jim crow/one drop rule era but he would have nener passed for white lol

Nah. Gotta disagree. He could have. Well, they definitely knew he was mulatto or - Free Person or Color..

Last edited: