Automation and offshoring may be conspiring to reduce labor's share of income.

Maybe he had a point.

Back in April, I wrote about one of the most troubling mysteries in economics, the falling labor share. Less of the income the economy produces is going to people who work, and more is going to people who own things.

See interactive chart: Less of the Pie for Labor

This trend is worrying because it contributes to increased inequality -- poor people own much less of the land and capital in the economy than rich people do. The devaluation of workers could also increase unemployment, social unrest and general malaise. No one would like to see capitalism transform into the kind of dystopia envisioned by Karl Marx. That’s why even though the decline in labor’s share has so far been relatively modest, economists are racing to diagnose the cause before the problem gets any worse.

Recently, a lot of attention has focused on the idea that monopoly power might be causing the shift. But the famous paper that draws this connection -- by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence Katz, Christina Patterson and John Van Reenen -- also shows that it can account for perhaps only 20 percent of the change. This means other possible explanations for labor's decline, like increasing automation or globalization, need to be re-examined.

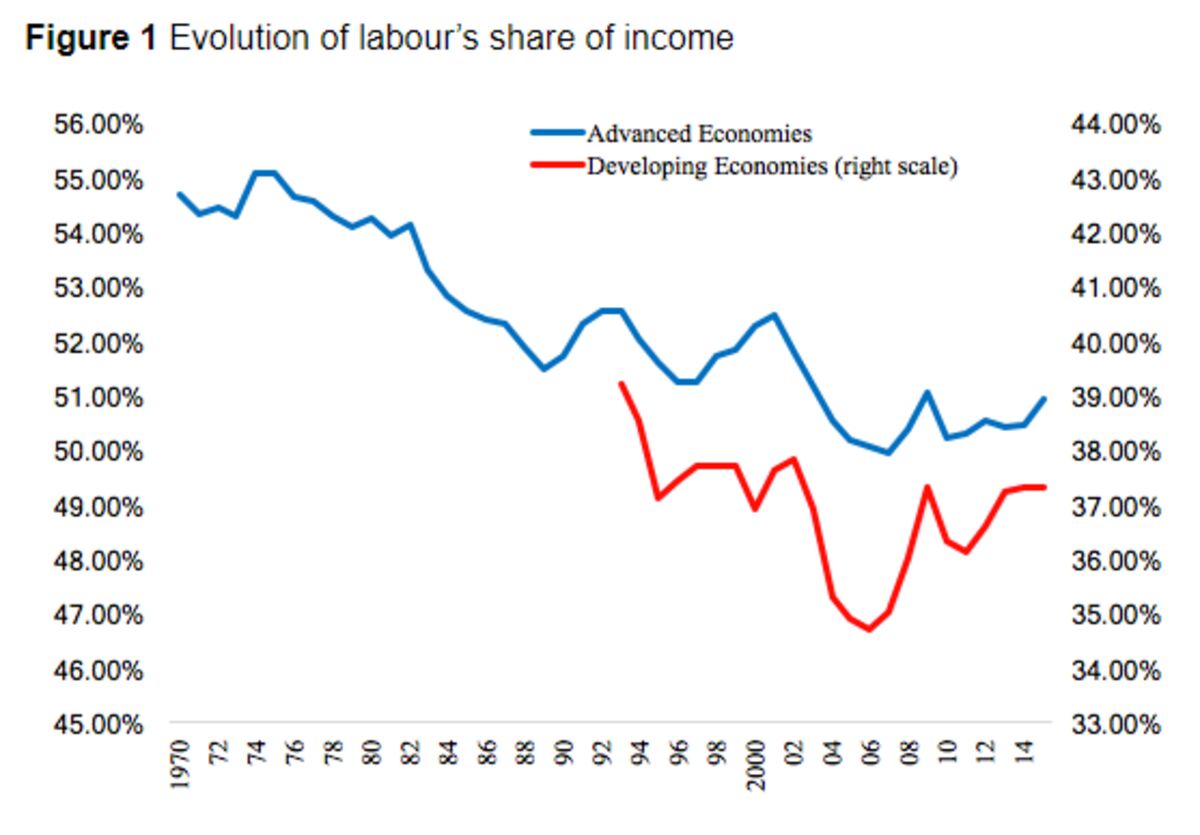

Economists Mai Dao, Mitali Das, Zsoka Koczan and Weicheng Lian of the International Monetary Fund argue that the culprit is not automation or offshoring alone, but the interaction between the two. As evidence, they note that the labor share has been falling not just in rich nations, but in developing countries as well. Here is a figure from their paper:

If globalization were purely to blame, this wouldn’t be happening. Standard trade theories imply that because rich countries have a lot of capital and poor countries have a lot of labor, when these countries start to trade, labor’s share of income should go down in the countries where it used to be scarce -- i.e., the rich world -- but should rise in the poor countries where it was previously abundant. That’s not what’s happening.

Meanwhile, if automation is just now starting to make workers obsolete, developing countries shouldn’t be experiencing the fall in labor share at the same time, because in technological terms they’re decades behind the rich countries. The authors confirm that investment goods -- machines, vehicles, computers, etc. -- haven’t really gotten much cheaper in poor countries, as they have in rich ones. So the puzzle really boils down to this: Why is the labor share falling in the developing world?

Dao and her co-authors offer a hypothesis. It has to do with the types of industries that exist in poor countries before and after trade gets opened up. When poor countries are isolated from the global economy, they tend to specialize in things that rely on a lot of cheap labor -- farming, low-end services and simple labor-intensive manufacturing. Local landlords and other capital owners do well, but don’t have a chance to get truly rich, because any investment in machinery or technology can be undercut by a flood of low-wage workers. So they don’t bother making the investments in the first place. This dearth of capital spending is exacerbated by rudimentary or dysfunctional financial systems.

But when trade opens up, the rich countries start offshoring manufacturing jobs to the poor countries. These jobs offer better opportunities for workers, but much better opportunities for capitalists. Even as capitalists in the U.S. or Japan or France get rich cutting labor costs by shipping jobs to China, Chinese capitalists get rich because they’re finally able to amass huge business empires.

The IMF economists also predict that global financial integration should help alleviate the pressure on labor in poor countries. If American, European, Japanese and Taiwanese companies are able to invest in a developing country like China, the inflow of foreign money will boost incomes for local workers and compete down the profits of local capital owners.

So what about rich countries? Here, the argument is that automation and globalization are working together -- companies in rich countries can ship labor-intensive manufacturing jobs in electronics assembly, toys and clothing to China and Bangladesh, while buying advanced machine tools and robots to do more high-end manufacturing of things like microprocessors and airplanes. As a result, workers in rich countries where routine jobs were more common were hit harder by both free trade and the advent of cheap automation.

In other words, the two most conventional explanations for rising inequality and falling wages might both be correct. A perfect storm of robots and free trade -- and some monopoly power to boot -- could be shifting power from the proletariat to the capitalists. With all these factors at work, maybe the real puzzle is why workers aren’t doing even worse than they are.

Maybe he had a point.

Back in April, I wrote about one of the most troubling mysteries in economics, the falling labor share. Less of the income the economy produces is going to people who work, and more is going to people who own things.

See interactive chart: Less of the Pie for Labor

This trend is worrying because it contributes to increased inequality -- poor people own much less of the land and capital in the economy than rich people do. The devaluation of workers could also increase unemployment, social unrest and general malaise. No one would like to see capitalism transform into the kind of dystopia envisioned by Karl Marx. That’s why even though the decline in labor’s share has so far been relatively modest, economists are racing to diagnose the cause before the problem gets any worse.

Recently, a lot of attention has focused on the idea that monopoly power might be causing the shift. But the famous paper that draws this connection -- by David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence Katz, Christina Patterson and John Van Reenen -- also shows that it can account for perhaps only 20 percent of the change. This means other possible explanations for labor's decline, like increasing automation or globalization, need to be re-examined.

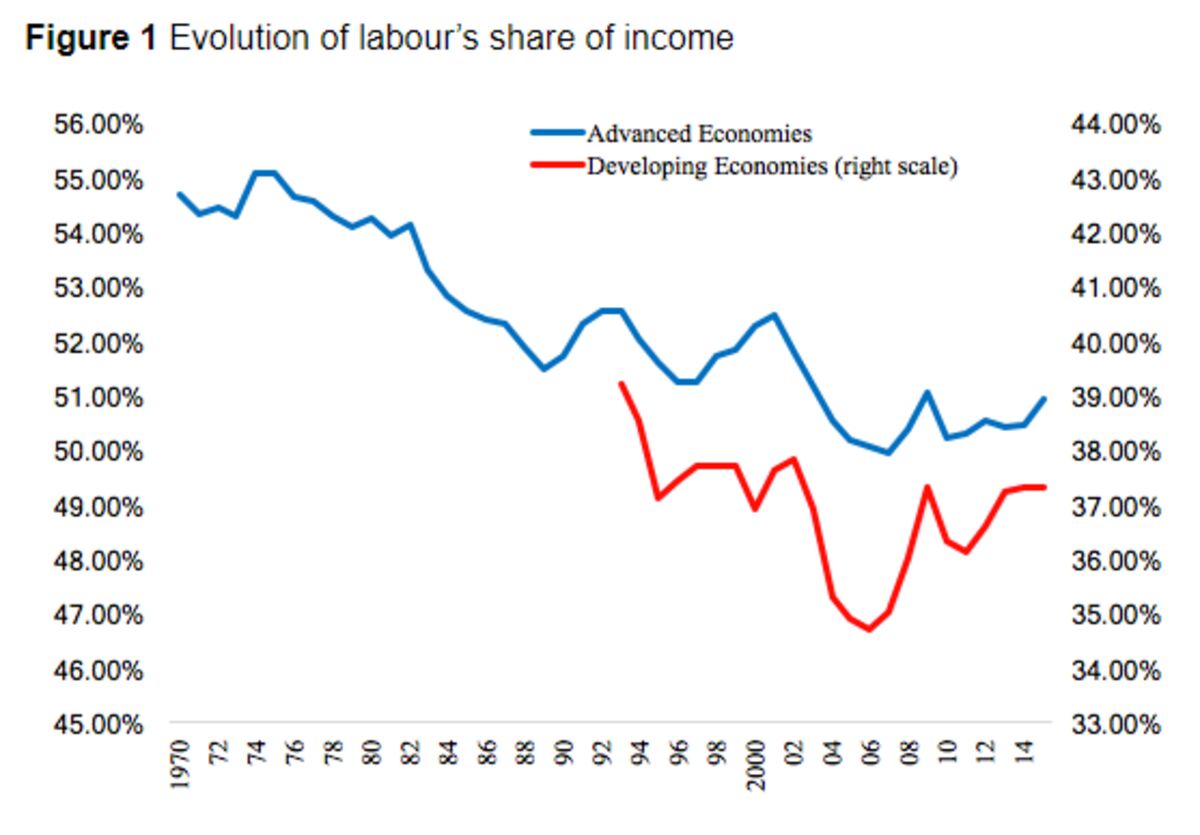

Economists Mai Dao, Mitali Das, Zsoka Koczan and Weicheng Lian of the International Monetary Fund argue that the culprit is not automation or offshoring alone, but the interaction between the two. As evidence, they note that the labor share has been falling not just in rich nations, but in developing countries as well. Here is a figure from their paper:

If globalization were purely to blame, this wouldn’t be happening. Standard trade theories imply that because rich countries have a lot of capital and poor countries have a lot of labor, when these countries start to trade, labor’s share of income should go down in the countries where it used to be scarce -- i.e., the rich world -- but should rise in the poor countries where it was previously abundant. That’s not what’s happening.

Meanwhile, if automation is just now starting to make workers obsolete, developing countries shouldn’t be experiencing the fall in labor share at the same time, because in technological terms they’re decades behind the rich countries. The authors confirm that investment goods -- machines, vehicles, computers, etc. -- haven’t really gotten much cheaper in poor countries, as they have in rich ones. So the puzzle really boils down to this: Why is the labor share falling in the developing world?

Dao and her co-authors offer a hypothesis. It has to do with the types of industries that exist in poor countries before and after trade gets opened up. When poor countries are isolated from the global economy, they tend to specialize in things that rely on a lot of cheap labor -- farming, low-end services and simple labor-intensive manufacturing. Local landlords and other capital owners do well, but don’t have a chance to get truly rich, because any investment in machinery or technology can be undercut by a flood of low-wage workers. So they don’t bother making the investments in the first place. This dearth of capital spending is exacerbated by rudimentary or dysfunctional financial systems.

But when trade opens up, the rich countries start offshoring manufacturing jobs to the poor countries. These jobs offer better opportunities for workers, but much better opportunities for capitalists. Even as capitalists in the U.S. or Japan or France get rich cutting labor costs by shipping jobs to China, Chinese capitalists get rich because they’re finally able to amass huge business empires.

The IMF economists also predict that global financial integration should help alleviate the pressure on labor in poor countries. If American, European, Japanese and Taiwanese companies are able to invest in a developing country like China, the inflow of foreign money will boost incomes for local workers and compete down the profits of local capital owners.

So what about rich countries? Here, the argument is that automation and globalization are working together -- companies in rich countries can ship labor-intensive manufacturing jobs in electronics assembly, toys and clothing to China and Bangladesh, while buying advanced machine tools and robots to do more high-end manufacturing of things like microprocessors and airplanes. As a result, workers in rich countries where routine jobs were more common were hit harder by both free trade and the advent of cheap automation.

In other words, the two most conventional explanations for rising inequality and falling wages might both be correct. A perfect storm of robots and free trade -- and some monopoly power to boot -- could be shifting power from the proletariat to the capitalists. With all these factors at work, maybe the real puzzle is why workers aren’t doing even worse than they are.