newworldafro

DeeperThanRapBiggerThanHH

Why Google Maps gets Africa wrong

From colonial cartographers to digital depictions the continent is being sold short, says Think Africa Press

James Wan for Think Africa Press, part of the Guardian Africa network

About halfway through Jonathan Swift's boisterously witty epic poem On Poetry: A Rhapsody, the 18th century Anglo-Irish satirist briefly turns his attention to maps of Africa, writing:

So geographers, in Afric maps,

With savage pictures fill their gaps,

And o'er uninhabitable downs

Place elephants for want of towns.

In Swift's time, European explorers had only skirted around the coastal edges of Africa and its interior remained, to all intents and purposes, a mystery. But as the poet pointed out, rather than just leave the middle of the continent blank, mapmakers would instead "fill their gaps" with things they thought might reside in such exotic corners of the world, such as strange monkeys, roaming lions, and "elephants for want of towns."

From Willem Janszoon Blaeu's 17th Century map of Africa

These elephants were largely marched off maps of Africa in the 19th century as expeditions by the likes of David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley provided more information to Europeans about the continent's geography. But these explorations were fairly narrow in scope, and the vast bulk of Africa would remain terra incognita for years to come.

In fact, even at the 1885 Berlin Conference where, legend has it, Europe's colonial powers each drew lines across a map of Africa and coloured in their territories with their imperial hue-of-choice, the colonialists weren't really sure what those areas contained. Although cartographers had given up their predilection for doodling odd creatures across Africa's interior, there wasn't a whole lot more they could put there instead.

These maps of Africa, drawn up by a small group of western cartographers, symbolically reinforced Europeans' sense of control over their mapped territories and subjects, but they didn't betray much in the way of real information. Though they would have been seen as objective and impartial at the time, in retrospect it is clear how subjective, ideologically driven, and, in many ways, fantastical they were.

Fast-forwarding to today it may seem like the situation is completely different. Any gaps in our geographical knowledge have been painstakingly filled in thanks to advanced technologies and satellite imagery. Access to maps is no longer confined to a small western elite. And mapmaking no longer seems so ideologically charged, but far more scientific and technical.

Unlike the age in which Africa was patchily mapped through a distinctly colonialist lens, one could argue that today, we all finally know what the continent − and indeed the world − actually looks like.

But things may not have changed as much as one might assume. No map is completely objective and every cartographer has to make countless decisions over what is more important and what is less so. Some of these choices may be purely technical, some may be issues of historical convention, and some may be informed by ideological assumptions. But these decisions − as invisible as they are in the final product − have to be made and they all fundamentally change how we see the world.

In today's maps, Africa arguably gets as rough a deal as it always has. Now as ever, the continent may not look like we think it does.

Mapping the corners of the world

One way in which we imagine Africa is through world maps. But as far back as Ptolemy, in the 2nd Century Roman empire, cartographers have known that drawing an accurate map of the world is basically impossible. The world is spherical, a map is flat, and there is no obvious way to get around this.

Try to flatten out, for example, the hollow peel of an orange and two things become quickly apparent: 1) there are an infinite number of ways to do that, and 2) none is particularly satisfactory, let alone a neat rectangle.

This problem has always haunted cartographers and the shapes of world maps have typically been hugely diverse, ranging from hearts...

Johannes Stabius' pseudoconical projection (~1500).

...to half-circles...

A pseudocylindrical projection used by various cartographers (1600s).

This diversity faded away, however, as one particular model gradually surpassed all the others to become the world map that is now ubiquitous on classroom walls, in books and now even on Google Maps. For many people today, that projection − invented by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569 − is the world map.

The main reason Mercator's projection became so popular was because of its navigational usefulness; in his map, straight lines represent lines of constant compass bearing. However, in manipulating the map to ensure this feature, the sizes of countries become hugely distorted. In particular, the southern hemisphere appears much smaller than it is in reality.

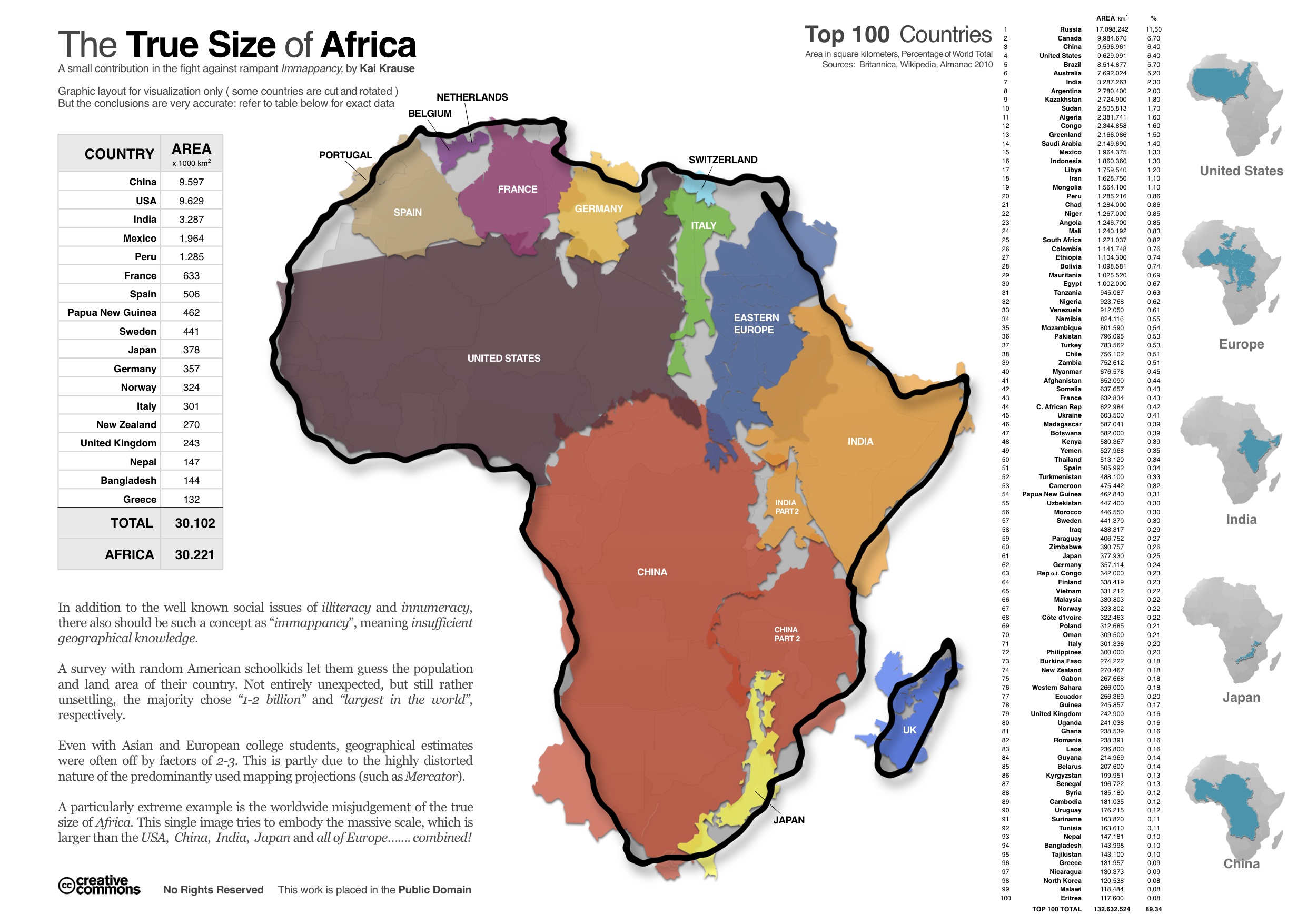

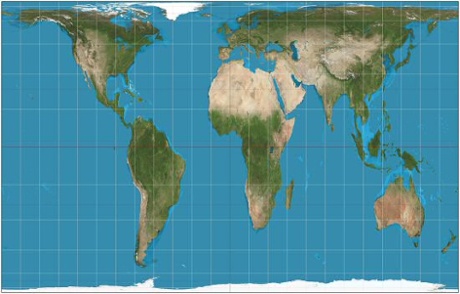

For instance, in the Mercator projection (below), north America looks at least as big, if not slightly larger, than Africa. And Greenland also looks of comparable size.

The ever-popular Mercator map of the world.

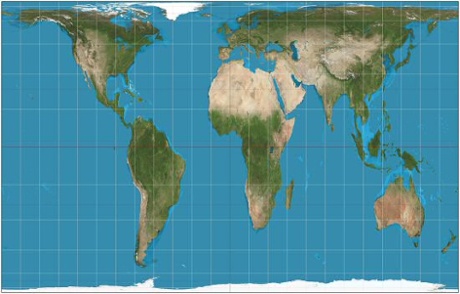

The Gall-Peters equal projection map, giving the correct proportion of land mass to the continents.

:ohh:

:ohh:

Another age-old convention that has subtly but seemingly innocuously under-privileged the southern hemisphere comes from the fact that the north is always put at the top. This was not always the case. In medieval Christian maps, east was located at the top because it was believed the world and the garden of Eden emanated from the east. Meanwhile in Islamic maps of around the same period, south was up.

The fact that our maps typically put north at the top is a mere convention. But like with Mercator's various technical manipulations, very minor decisions can have very major effects on how we see the world.

It would of course be silly to speculate on whether world history would have taken any different turns if our basic cartographic conventions had been different over the last half a millennium, but imagine for a moment that when we pictured the world we live in, we all thought of this:

The Gall-Peters equal projection map, but the other way up this time.

From colonial cartographers to digital depictions the continent is being sold short, says Think Africa Press

James Wan for Think Africa Press, part of the Guardian Africa network

- theguardian.com, Wednesday 2 April 2014 04.43 EDT

About halfway through Jonathan Swift's boisterously witty epic poem On Poetry: A Rhapsody, the 18th century Anglo-Irish satirist briefly turns his attention to maps of Africa, writing:

So geographers, in Afric maps,

With savage pictures fill their gaps,

And o'er uninhabitable downs

Place elephants for want of towns.

In Swift's time, European explorers had only skirted around the coastal edges of Africa and its interior remained, to all intents and purposes, a mystery. But as the poet pointed out, rather than just leave the middle of the continent blank, mapmakers would instead "fill their gaps" with things they thought might reside in such exotic corners of the world, such as strange monkeys, roaming lions, and "elephants for want of towns."

From Willem Janszoon Blaeu's 17th Century map of Africa

These elephants were largely marched off maps of Africa in the 19th century as expeditions by the likes of David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley provided more information to Europeans about the continent's geography. But these explorations were fairly narrow in scope, and the vast bulk of Africa would remain terra incognita for years to come.

In fact, even at the 1885 Berlin Conference where, legend has it, Europe's colonial powers each drew lines across a map of Africa and coloured in their territories with their imperial hue-of-choice, the colonialists weren't really sure what those areas contained. Although cartographers had given up their predilection for doodling odd creatures across Africa's interior, there wasn't a whole lot more they could put there instead.

These maps of Africa, drawn up by a small group of western cartographers, symbolically reinforced Europeans' sense of control over their mapped territories and subjects, but they didn't betray much in the way of real information. Though they would have been seen as objective and impartial at the time, in retrospect it is clear how subjective, ideologically driven, and, in many ways, fantastical they were.

Fast-forwarding to today it may seem like the situation is completely different. Any gaps in our geographical knowledge have been painstakingly filled in thanks to advanced technologies and satellite imagery. Access to maps is no longer confined to a small western elite. And mapmaking no longer seems so ideologically charged, but far more scientific and technical.

Unlike the age in which Africa was patchily mapped through a distinctly colonialist lens, one could argue that today, we all finally know what the continent − and indeed the world − actually looks like.

But things may not have changed as much as one might assume. No map is completely objective and every cartographer has to make countless decisions over what is more important and what is less so. Some of these choices may be purely technical, some may be issues of historical convention, and some may be informed by ideological assumptions. But these decisions − as invisible as they are in the final product − have to be made and they all fundamentally change how we see the world.

In today's maps, Africa arguably gets as rough a deal as it always has. Now as ever, the continent may not look like we think it does.

Mapping the corners of the world

One way in which we imagine Africa is through world maps. But as far back as Ptolemy, in the 2nd Century Roman empire, cartographers have known that drawing an accurate map of the world is basically impossible. The world is spherical, a map is flat, and there is no obvious way to get around this.

Try to flatten out, for example, the hollow peel of an orange and two things become quickly apparent: 1) there are an infinite number of ways to do that, and 2) none is particularly satisfactory, let alone a neat rectangle.

This problem has always haunted cartographers and the shapes of world maps have typically been hugely diverse, ranging from hearts...

Johannes Stabius' pseudoconical projection (~1500).

...to half-circles...

A pseudocylindrical projection used by various cartographers (1600s).

This diversity faded away, however, as one particular model gradually surpassed all the others to become the world map that is now ubiquitous on classroom walls, in books and now even on Google Maps. For many people today, that projection − invented by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569 − is the world map.

The main reason Mercator's projection became so popular was because of its navigational usefulness; in his map, straight lines represent lines of constant compass bearing. However, in manipulating the map to ensure this feature, the sizes of countries become hugely distorted. In particular, the southern hemisphere appears much smaller than it is in reality.

For instance, in the Mercator projection (below), north America looks at least as big, if not slightly larger, than Africa. And Greenland also looks of comparable size.

The ever-popular Mercator map of the world.

The Gall-Peters equal projection map, giving the correct proportion of land mass to the continents.

:ohh:

:ohh:

Another age-old convention that has subtly but seemingly innocuously under-privileged the southern hemisphere comes from the fact that the north is always put at the top. This was not always the case. In medieval Christian maps, east was located at the top because it was believed the world and the garden of Eden emanated from the east. Meanwhile in Islamic maps of around the same period, south was up.

The fact that our maps typically put north at the top is a mere convention. But like with Mercator's various technical manipulations, very minor decisions can have very major effects on how we see the world.

It would of course be silly to speculate on whether world history would have taken any different turns if our basic cartographic conventions had been different over the last half a millennium, but imagine for a moment that when we pictured the world we live in, we all thought of this:

The Gall-Peters equal projection map, but the other way up this time.

Pretty interesting..

Pretty interesting..