Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone in "La La Land."

Source: Dale Robinette/Lionsgate

In handicapping the Oscar race for Best Picture, it’s best to follow the money–or, more accurately, the lack thereof.

The nine films announced on Tuesday in the running for the coveted Academy Award crushed it with critics, but they didn’t win much in the way of crowds. At the box office, they’ve rounded up an average of $53.5 million in ticket sales, which would rank No. 67 out of all films released in 2016. La La Land, a favorite that already won a Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy, leads the pack with $89.8 million in domestic theaters. Moonlight, which also won a Golden Globe for Best Drama, trails with $15.8 million.

The structure is not unlike the Electoral College: The popular vote doesn’t always carry the day. Top-grossing films Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and Finding Dory will have to shop for statuary in other categories.

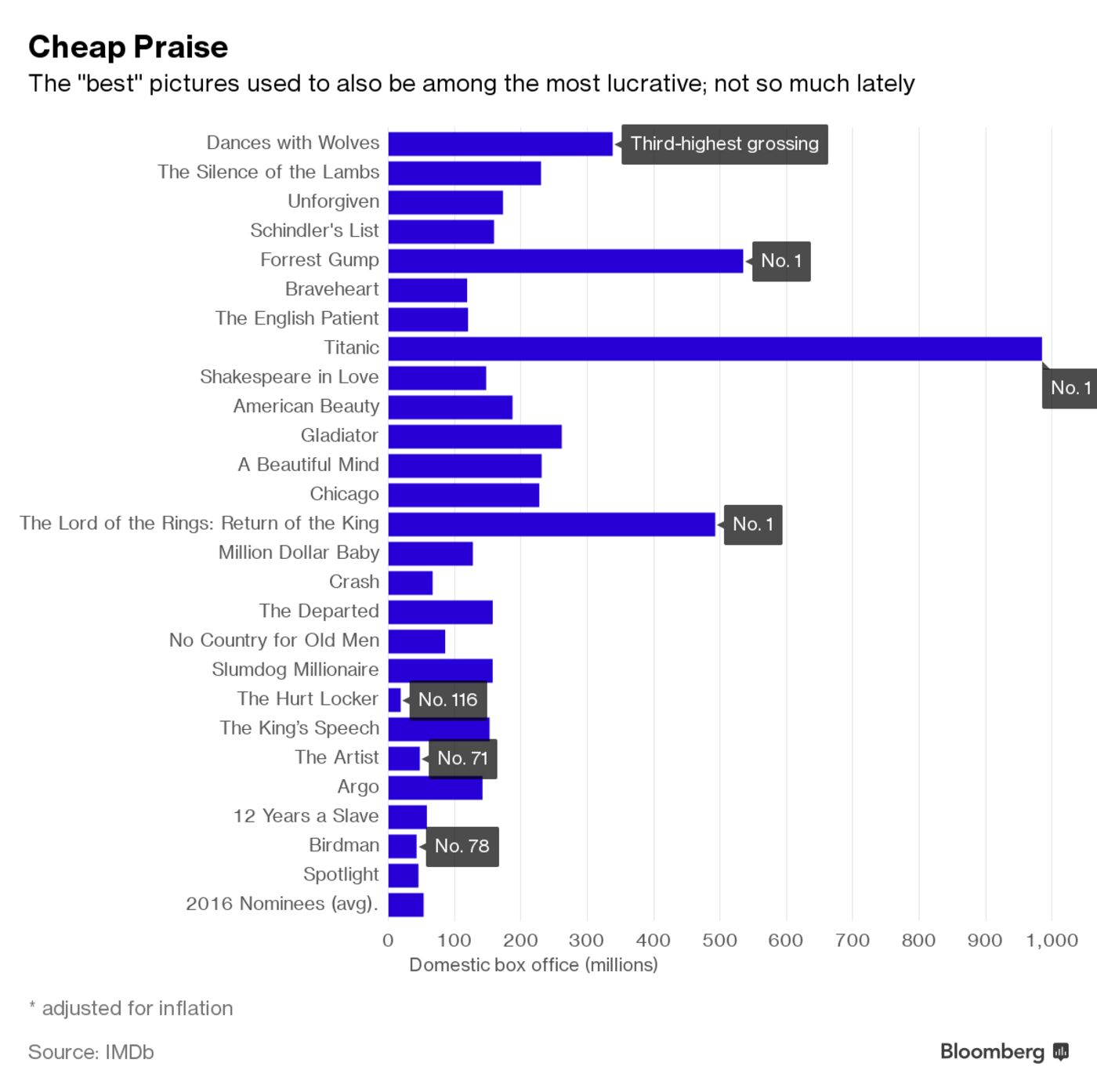

This is nothing new. The “best” picture, of late, is seldom a big picture. The Best Picture Oscar winner hasn’t cracked the top 10 moneymakers since 2003, when The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King, took the golden statue.

It wasn’t always this way, however. In the 1990s, the Academy’s top film was often a blockbuster, from Dances With Wolves and The Silence of the Lambs to Titanic and Gladiator.

So why have the tastes of moviegoers become so thoroughly uncoupled from those of critics? Why do our dollars no longer track our finer sensibilities? One theory is that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—the 7,000 or so filmmakers, actors, writers, and PR professionals who vote on the films—are out of touch with the popcorn-greased fingers of hoi polloi.

That was roughly the take of Vin Diesel when he assessed the odds of his Furious 7 in March 2015: “It will probably win best picture at the Oscars,” he told Variety. “Unless the Oscars don’t want to be relevant ever.”

Despite Diesel’s fine addition to the car-chase canon (and grade-A trolling), Furious didn’t prevail. But something else is going on: There are more movies these days, and Americans, on average, are going to the movies less. While attendance has remained static, according to the Motion Picture Association of America, that’s largely because there are more people.

Since the mid-1990s, ticket sales per capita has ticked down. The average American goes to slightly fewer than four films a year now, down from about five in 1996.

Meanwhile, the number of movies released spiked 50 percent over the same period. In 2015, there were 708 films to choose from, including the “best” one, Spotlight, and the biggest one, Star Wars: The Force Awakens. What’s more, 40 of the movies got the 3D treatment.

When we do tear ourselves away from Netflix these days, we spend on the spectacle and save the headier fare for home viewing ... if we watch it at all.

Why Best Picture Nominees Fare Poorly at the Box Office