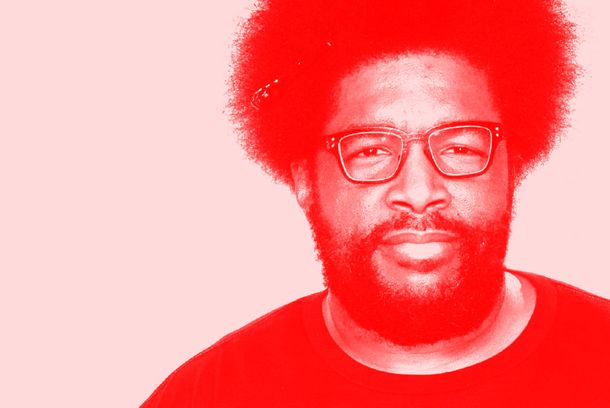

Questlove on How Hip-Hop Failed Black America -- Vulture

There are three famous quotes that haunt me and guide me though my days. The first is from John Bradford, the 16th-century English reformer. In prison for inciting a mob, Bradford saw a parade of prisoners on their way to being executed and said, “There but for the grace of God go I.” (Actually, he said “There but for the grace of God goes John Bradford,” but the switch to the pronoun makes it work for the rest of us.) The second comes from Albert Einstein, who disparagingly referred to quantum entanglement as “spooky action at a distance.” And for the third, I go to Ice Cube, the chief lyricist of N.W.A., who delivered this manifesto in “Gangsta Gangsta” back in 1988: “Life ain’t nothing but bytches and money.”

Those three ideas may seem distant from one another, but if you set them up and draw lines between them, that’s triangulation. Bradford’s idea, of course, is about providence, about luck and gratitude: You only have your life because you don’t have someone else’s. At the simplest level, I think about that often. I could be where others are, and by extension, they could be where I am. You don’t want to be insensible to that. You don’t want to be an ingrate. (By the by, Bradford’s quote has come to be used to celebrate good fortune — when people say it, they’re comforting themselves with the fact that things could be worse — but in fact, his own good fortune lasted only a few years before he was burned at the stake.)

Einstein was talking about physics, of course, but to me, he’s talking about something closer to home — the way that other people affect you, the way that your life is entangled in theirs whether or not there’s a clear line of connection. Just because something is happening to a street kid in Seattle or a small-time outlaw in Pittsburgh doesn’t mean that it’s not also happening, in some sense, to you. Human civilization is founded on a social contract, but all too often that gets reduced to a kind of charity: Help those who are less fortunate, think of those who are different. But there’s a subtler form of contract, which is the connection between us all.

And then there’s Ice Cube, who seems to be talking about life’s basic appetites — what’s under the lid of the id — but is in fact proposing a world where that social contract is destroyed, where everyone aspires to improve themselves and only themselves, thoughts of others be damned. What kind of world does that create?

Those three ideas, Bradford’s and Einstein’s and Cube’s, define the three sides of a triangle, and I’m standing in it with pieces of each man: Bradford’s rueful contemplation, Einstein’s hair, Ice Cube’s desires. Can the three roads meet without being trivial? This essay, and the ones that follow it, will attempt to find out. I’m going to do things a little differently, with some madness in my method. I may not refer back to these three thinkers and these three thoughts, but they’re always there, hovering, as I think through what a generation of hip-hop has wrought. And I’m not going to handle the argument in a straight line. But don’t wonder too much when it wanders. I’ll get back on track.

*

- Today at 11:45 AM

- 5 Comments

- By Questlove

There are three famous quotes that haunt me and guide me though my days. The first is from John Bradford, the 16th-century English reformer. In prison for inciting a mob, Bradford saw a parade of prisoners on their way to being executed and said, “There but for the grace of God go I.” (Actually, he said “There but for the grace of God goes John Bradford,” but the switch to the pronoun makes it work for the rest of us.) The second comes from Albert Einstein, who disparagingly referred to quantum entanglement as “spooky action at a distance.” And for the third, I go to Ice Cube, the chief lyricist of N.W.A., who delivered this manifesto in “Gangsta Gangsta” back in 1988: “Life ain’t nothing but bytches and money.”

Those three ideas may seem distant from one another, but if you set them up and draw lines between them, that’s triangulation. Bradford’s idea, of course, is about providence, about luck and gratitude: You only have your life because you don’t have someone else’s. At the simplest level, I think about that often. I could be where others are, and by extension, they could be where I am. You don’t want to be insensible to that. You don’t want to be an ingrate. (By the by, Bradford’s quote has come to be used to celebrate good fortune — when people say it, they’re comforting themselves with the fact that things could be worse — but in fact, his own good fortune lasted only a few years before he was burned at the stake.)

Einstein was talking about physics, of course, but to me, he’s talking about something closer to home — the way that other people affect you, the way that your life is entangled in theirs whether or not there’s a clear line of connection. Just because something is happening to a street kid in Seattle or a small-time outlaw in Pittsburgh doesn’t mean that it’s not also happening, in some sense, to you. Human civilization is founded on a social contract, but all too often that gets reduced to a kind of charity: Help those who are less fortunate, think of those who are different. But there’s a subtler form of contract, which is the connection between us all.

And then there’s Ice Cube, who seems to be talking about life’s basic appetites — what’s under the lid of the id — but is in fact proposing a world where that social contract is destroyed, where everyone aspires to improve themselves and only themselves, thoughts of others be damned. What kind of world does that create?

Those three ideas, Bradford’s and Einstein’s and Cube’s, define the three sides of a triangle, and I’m standing in it with pieces of each man: Bradford’s rueful contemplation, Einstein’s hair, Ice Cube’s desires. Can the three roads meet without being trivial? This essay, and the ones that follow it, will attempt to find out. I’m going to do things a little differently, with some madness in my method. I may not refer back to these three thinkers and these three thoughts, but they’re always there, hovering, as I think through what a generation of hip-hop has wrought. And I’m not going to handle the argument in a straight line. But don’t wonder too much when it wanders. I’ll get back on track.

*