continued ...

What he once did in Harlem, building houses for his father's construction company, then building sweat equity in a black real estate cooperative, Robinson, 53, is doing in a different way in Africa. He views his work as a melding of black aspirations from both sides of the Atlantic.

He called himself a pan-Africanist during the 1970s when many black activists in the United States and Africa espoused a common purpose. Robinson still hews to that ideal, though now he calls himself a "humanist." His focus, though, remains the same: lifting the race, as folks used to say in his father's day.

One wonders whether his father would approve of his son's African life.

"He would recognize the intent of opening opportunity and developing potential, which was very much the focus of his life," says Robinson during an interview on the Mall at his Folklife Festival display.

"He would be perplexed at why that needed to be done 10,000 miles away, in Africa, rural Africa particularly."

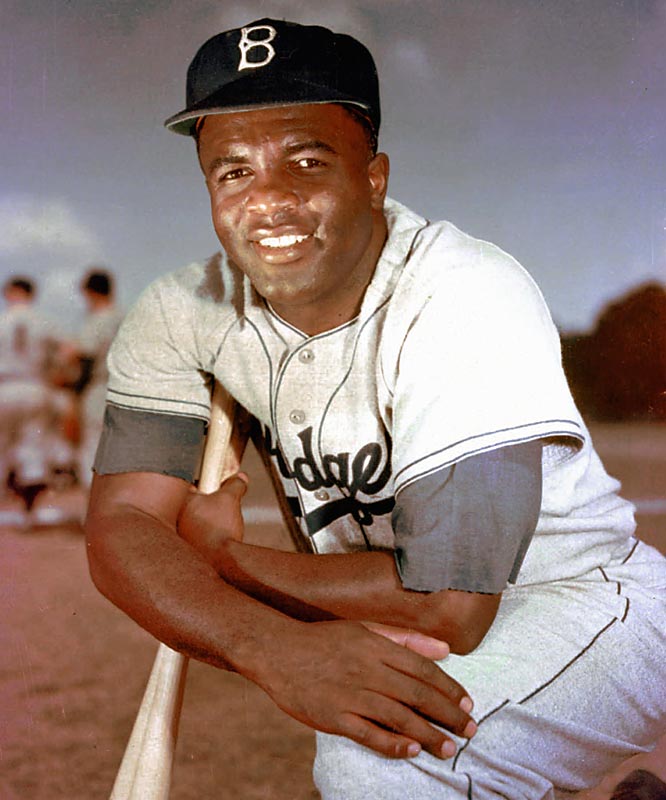

Africa imprinted itself on Robinson's consciousness at the age of 14, during his youthful travels there with his mother, Rachel Robinson.

Five years later, he spent nearly a year roaming the continent following the 1971 death of his big brother, Jackie Jr., who had become addicted to heroin while serving in Vietnam and died in an automobile accident, driving David's car.

His death ripped the family's heart. Rachel Robinson, now 82, wrote in her 1996 memoir, "Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait," "In that moment I felt we had gained so much in life and lost it all when we lost our Jackie." (Jackie Sr. would die a year later.)

"When Jackie Jr. was killed, David spent a year walking the east coast of Africa by himself," Rachel Robinson recalls. "That told me something about where he went for comfort and where he went to deal with the grief."

So when he moved there, she was not altogether surprised. But she has worried, she says, that his life there would become a rejection of America.

Robinson says that wasn't the point.

"I wasn't leaving America," he says. "I never left America forever. I wasn't going to sit up on a mountaintop in Africa or a beach in Africa and just chill and stay there. It was always going to be about how black people in America and Africa need each other."

And it was also, for him, a way to recapture the sense of identity that he feels within the African American community. He compares it to trauma, a kind of psychic branding, passed from generation to generation.

Robinson moved to Tanzania 21 years ago, first settling in the capital, Dar es Salaam. Initially, he tried exporting African art. Then he tried the fish trade. Finally he moved into coffee.

Out in the lush highlands of the Mbozi district of the southwestern Tanzania region whose coffee is praised the world over, Robinson has built a life, raised a family and seen his goals begin to flower.

Among African Americans who move to Africa, Robinson is relatively unusual for plunging deep into the African wilderness. His 280-acre farm, called Sweet Unity, includes 60 acres that he and one of his sons cleared. Robinson enlists up to 50 relatives and neighbors from other farms to harvest his coffee; similarly he helps with neighboring harvests.

It is part of the Mshikamano Farmers Group, a 10-year-old cooperative whose product, Sweet Unity Farms coffee, is featured at the Folklife Festival's Food Culture USA program.

Robinson, as the group's marketing manager, is seeking new retail and corporate clients. To earn better prices for the crops of Mshikamano's 300 coffee farms, Robinson is swimming against the currents of the global coffee trade by trying to market their product directly to buyers. (Sweet Unity Farms coffee can be found in markets in Atlanta and New York, but not yet in the District.)

And Robinson and the cooperative are battling Mbozi's unforgiving environment, filled with malaria, backbreaking work, a history of poverty and farming failures.

As a driving force in starting Mshikamano, Robinson found his presence duly noted by grant makers at the African Development Foundation, a U.S.-government organization, which awarded the cooperative $210,000 this year for such supports as tools and fertilizers.

"The fact that he would move there, start a family there, live in the village with no electricity, no running water: It's quite a commitment," says Tom Coogan, ADF's representative for eastern and southern Africa. "And I think he really understood at the local level both what the farmers needed and how he could help."

In Tanzania, Robinson is affectionately known, in Kiswahili, as M negro (the Negro). His life takes the appellation "African American" to a whole new level, for Robinson is living an African life, not just acknowledging Africa with a name.

In 1990, he petitioned local authorities in Mbozi for land, which meant explaining why he, a non-Tanzanian, should be granted such a privilege. Despite letters of introduction from government contacts on the coast, his first couple of pitches were rejected. The third village, Bara, seemed more open to the idea.

Robinson presented himself to the village authorities as a descendant of Africa, once separated from the continent and its tribes by slavery, who had returned to claim a place.

"Traditionally in an African society, a social member, a tribal member, has a village and all villagers look out for and will allocate land to their members," he explains.

So he told them, "By history, I lost my location. But I am choosing this location and I want you, based on that principle, to give me some consideration."

The village's "political science committee" unanimously approved his petition and gave him a piece of remote forest land a 45-minute walk from the nearest farm.

Robinson then began his search for a bride. A family of the Wanyamwezi tribe adopted him to assist in the process (one can't just show up in rural Africa and ask a young woman for a date). They sent a delegation out in the Mbozi region to prospect for marriage-aged women.

Robinson knew he wanted to meet a Nyamwezi woman because he thought they would share a similar consciousness as descendants of enslaved people. (The Wanyamwezi were heavily raided in the 19th century by Arab slave traders along Africa's east coast.) He also admits that he had his eye on the Wanyamwezi because its women are reputed to be beautiful.

Out of the search process emerged Ruti Mpunda, then 18. They have been married for 15 years, have grown to love one another, says Robinson, and have had seven children. One, named Jack, died from malaria at the age of 4 more than a decade ago.

The family lived in the remote village of Bara until three years ago. Robinson moved them to the capital, to be closer to proper schools. But he spends most of his time at the farm, at Sweet Unity.

From his land he can see Lake Rukwa, among the smaller lakes of the Great Rift Valley of Africa, just south of Lake Tanganyika. He can survey coffee lands, as far as the eye can see, that he will pass on to his children.

His father, after baseball, was an executive for the Chock Full O'Nuts coffee empire in New York. But Robinson doesn't think that influenced his choice of vocation. His workplace is deep in the African bush, a place his father would never have gone. (His mother has visited Tanzania several times, though the rough trek to the farm from the capital, about 16 hours by car, became too rigorous as her age advanced.)

Robinson is a celebrated figure in the region. A man who has committed himself to helping the farmers better their lives. An African American who has come back. Mnegro.

"They have no idea who Jackie Robinson is," says Coogan, who has traveled in the region. "They don't know what baseball is. But they're in awe of what David has done."

Robinson chuckles fondly as he uses the term that is archaic in America, saying, "The Negroes will always be remembered in Mbozi."