‘We don’t need air con’: how Burkina Faso builds schools that stay cool in 40C heat

Architects use local materials and merge traditional techniques with modern technology to make schools and orphanages cool, welcoming places

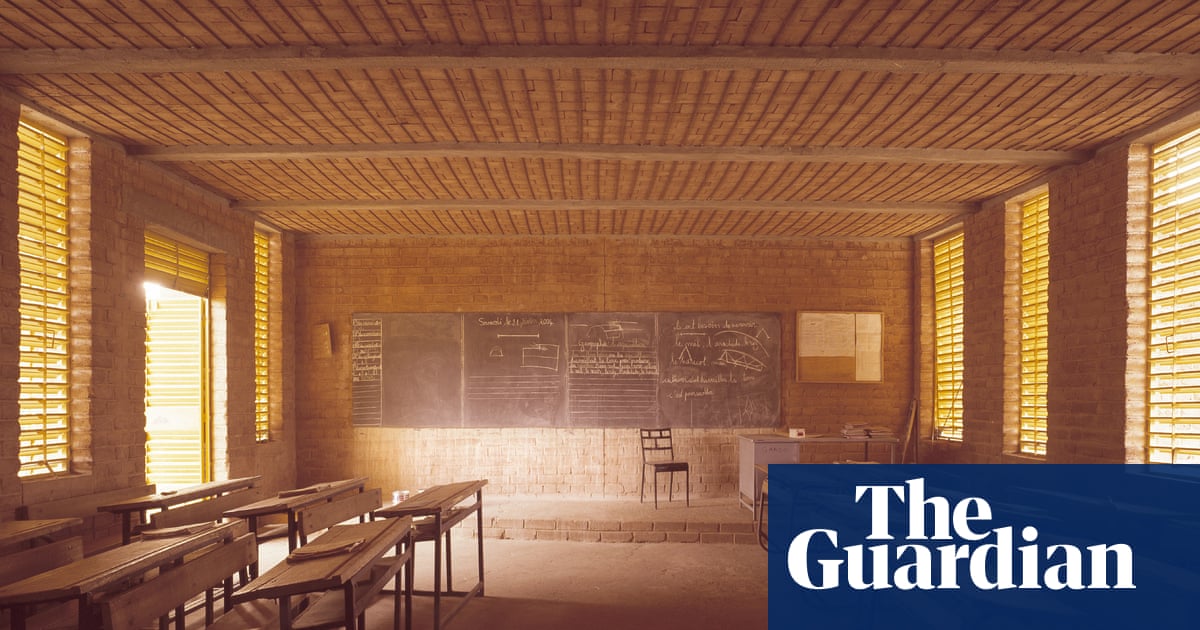

Gando primary school, Diébédo Francis Kéré’s first construction project after finishing his studies in Germany. Photograph: Siméon Duchoud/Kere Architecture

The alternatives

‘We don’t need air con’: how Burkina Faso builds schools that stay cool in 40C heat

Architects use local materials and merge traditional techniques with modern technology to make schools and orphanages cool, welcoming places

by Èlia Borràs in Burkina Faso

Thu 29 Feb 2024 07.43 EST

If architects are people who like to think their way around challenges, building schools in Burkina Faso must be the dream job. The challenges, after all, are legion: scorching temperatures in the high seasons, limited funds, materials, electricity and water, and clients who are vulnerable and young. How do you keep a building cool under a baking sun when there is no air conditioning?

Architect Diébédo Francis Kéré grew up in the small village of Gando and knows the challenges well. He and other architects such as Albert Faus are finding ingenious ways to use cheap materials to make sure that the schools and orphanages that they have built around Burkina Faso are cool, welcoming places.

Kéré, who won the Pritzker prize in 2022, has spoken movingly about the support he was given as a child by the whole community, with everyone giving money towards his education as he left the village and eventually gained a scholarship and studied in Germany. “The reason I do what I do is my community,” he said.

Gando primary school, built in 2001, was Kéré’s first construction after completing his studies. “At first, my community didn’t understand why I wanted to build with clay when there were glass buildings in Germany, so I had to convince them to use the local materials,” Kéré has said. Men and women came together to build the school, merging traditional techniques such as clay floors, beaten by hand until they were “smooth as a baby’s bottom” with more modern technology to seek better comfort.

The Noomdo orphanage, where metal plates above the rooms protect them from direct sunlight and rain. Photograph: Iwan Baan/Kere Architecture

The Noomdo orphanage was another of his projects. “The Kéré building provides us with good thermal comfort because when it’s hot, we’re cool, and when it’s cold, we’re warm inside,” says Pierre Sanou, a social educator at the orphanage near the city of Koudougou in the Centre-Ouest (centre-west) region of Burkina Faso. “We don’t need air conditioning, which is an incredible energy saving,” says Sanou. Temperatures in this region of the world remain at about 40C (104F) during the hottest season.

“Kéré builds with local materials from our territory like laterite stone and uses very little concrete,” says Sanou. Kéré’s buildings in Burkina Faso are earthy. They start from the ground and take into account that concrete is a material that needs to be transported to the site, is much more expensive and generates waste. “They are permeable buildings that seek the movement of natural air and protection from the sun. For example, they are built with very strong walls and very light roofs so that the cool air that enters from below pushes the hot air out from above,” says Eduardo González, a member of the Architecture School of Madrid.

One particularly ingenious innovation is his use of the ancient idea of raised and extended metal roofs. The rooms of Noomdo are covered by a shallow barrel vault resting on a concrete beam but with openings. Above, a metal plate protects the roof from direct sunlight and rain. Additionally, it lets out the hot air. González says the technique can be found in the vernacular architecture of the Persian Gulf. In Burkina Faso, he says Kéré integrates it into his projects and “gives this technique a contemporary image”.

Gando primary school, built by Kéré in 2001 with local materials, merging traditional techniques with more modern technology. Photograph: Enrico Cano/Kere Architecture

The orphanage, shaped in a semicircle, also takes into account the privacy of its users, most of whom are minors living in extremely vulnerable situations. While on one side there are boys’ dormitories, on the other side are girls’, with administration serving as a nexus between them. To maintain the privacy and security of the children, the building is designed with three visibility zones. The first is the entrance door, where a common room and kitchen are located. In the background, there is the interior common space where entry is permitted only with authorisation, and finally, the interior courtyards of the dormitories. “There are spaces to rest and be calm,” says Sanou. There are no fences or barbed wire.

Nearby, the Bangre Veenem school complex designed by Faus in the village of Youlou uses similarly ingenious ways to cool the building. Ousmane Soura works as an education adviser at the school. “Before building the school, [Faus] came to speak with the traditional authorities to obtain permission to build and to find out if there were sacred places that are sometimes not obvious or visible to people who don’t know them,” says Soura.

The Bangre Veenem school complex, designed by Albert Faus, was built with bricks made from laterite stone native to the area. Photograph: Milena Villalba/Milena Villalba 2020

The school complex accommodates everything from nursery to high school, including a professional school. “The students don’t say: ‘It’s really hot’ and want to go home because they’re comfortable and can concentrate with the class,” adds Soura.

It is built with bricks made from laterite stone native to the area. Laterite is shaped with a mould, dried in the sun, and becomes a brick of very intense red colour. “They are more resistant to bullets than concrete blocks, which have two holes in the centre,” says Soura.

Faus also managed to minimise material transportation and use the territory’s own materials. Even the quarry workers were from the area. “It’s a very beautiful material. When families see the buildings, they want their children to go to school,” says Soura. There are even teenagers who meet inside the classrooms to talk after class or during vacation periods. The complex is an open space.

Burkina Faso ranks 184th out of 191 countries in the Human Development Index and as of late 2020, only 22.5% of its population had access to electricity, according to data from the African Development Bank. “Students can come at night to study and charge their phones because there is light thanks to solar panels,” Soura says.

“Students are more focused because we have a good temperature in class. If the students, the administration, and teachers work well, and the environment is favourable in class, the results will be better. You know that hot weather disfavours students’ learning, and if we’re hot in class, we all feel tired, and eventually children prefer to sleep.”