US States Fail to Protect Children’s Rights

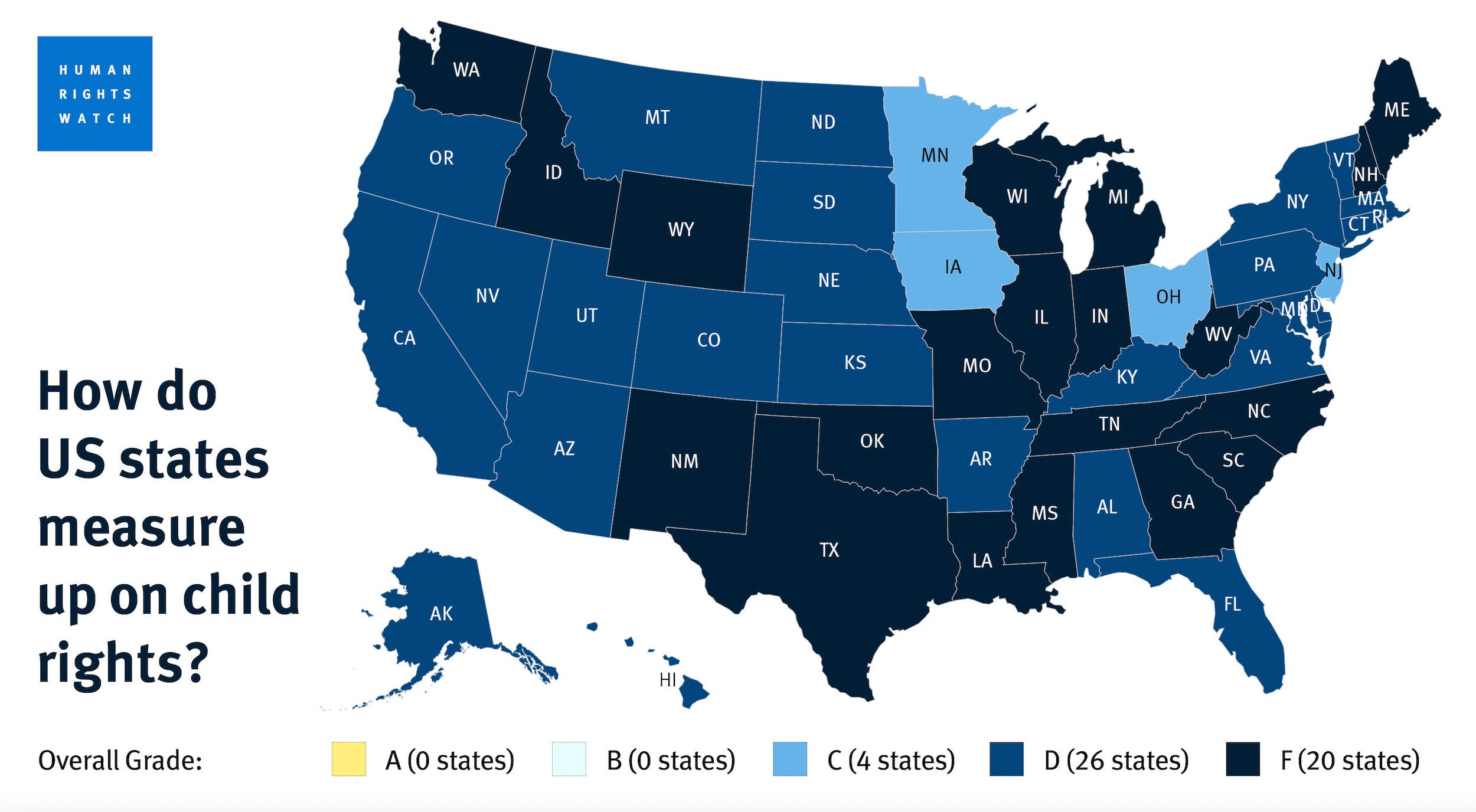

United States state laws overwhelmingly fail to meet international child rights standards, with the vast majority failing to protect children from child marriage, hazardous child labor, extreme prison sentences, and violent treatment.

A new Human Rights Watch interactive scorecard assessed 12 specific state laws in all 50 states against standards set by the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the primary international treaty on the rights of children. The laws address four issues: child marriage, corporal punishment, child labor, and juvenile justice. The United States is the only country that has failed to ratify the Convention, ratified by 196 countries.

“For people who believe the US is treating its children well, this assessment is a rude awakening,” said Jo Becker, children’s rights advocacy director for Human Rights Watch. “When it comes to child marriage, hazardous child labor, extreme prison sentences, and violent treatment of children, the vast majority of US states have abysmal laws. State policymakers should act quickly to better protect their children.”

The Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the United Nations in 1989, addresses children’s rights to education, health, an adequate standard of living, freedom of expression, protection from violence and exploitation, and a broad array of other rights.

In the United States, many of the issues addressed by the Convention are left to the jurisdiction of individual states, not the federal government, and there is wide variation from state to state. States with the worst grades include Mississippi, Wyoming, Oklahoma, Georgia, and Washington.

Child marriage is legal in 43 states. According to Unchained at Last, a group dedicated to ending child and forced marriage, over a quarter million children, some as young as 10, were married in the US between the years 2000 and 2018, the year Delaware became the first US state to prohibit child marriage. On July 28, 2022, Massachusetts became the seventh state to set the minimum age at 18, without exceptions, in line with international standards. Child marriage is associated with early pregnancy, lower educational achievement, and increased risk of domestic violence and poverty.

No US state has prohibited all corporal punishment of children, and 23 states allow it in both public and private schools. Approximately 160,000 children are subjected to corporal punishment in schools each year, according to data from the US Department of Education. Black children and children with disabilities are significantly more likely to experience corporal punishment in schools. Only two states, New Jersey and Iowa, prohibit corporal punishment in both public and private schools.

Corporal punishment in child penal institutions remains legal in 16 states. The Convention calls for protection of children “from all forms of physical and mental violence,” and UN experts state that the Convention “does not leave room for any level of legalized violence against children.” Corporal punishment has been found to be both ineffective in correcting children’s behavior and harmful to child development.

The United States remains the only country in the world that sentences children under 18 to life in prison without parole, which the Convention strictly prohibits. According to the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, 25 states prohibit these sentences. At the beginning of 2020, more than 1,400 people were serving life-without-parole sentences in the US for offenses committed as children, in some cases as young as age 13. Sixty-two percent of those serving sentences of life without parole for childhood offenses are Black, though they make up only 14 percent of the US youth population.

International children’s rights standards state that no child should be prosecuted as an adult. Research shows that youth not tried as adults are less likely to commit new crimes. Yet in the US, an estimated 53,000 children are tried in adult courts each year.

No US state prohibits prosecuting children in adult courts, and only 28 states have any age limits on transferring children to adult court. Not a single state sets the minimum age of juvenile jurisdiction to at least 14, the international standard, and more than 30,000 children under 12 are referred to juvenile court annually. Only five states, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Nebraska, set a minimum age higher than 10.

Weak protections in federal child labor law and regulations in the US fail to protect children working in agriculture, the most dangerous industry for child workers. Federal law allows children to work for hire in agriculture at younger ages, for longer hours, and in more hazardous conditions than in any other sector. A 2018 US government study found that children working in agriculture account for more than half of work-related fatalities, even though they represent just three percent of child workers.

For its scorecard, Human Rights Watch chose to focus on four issues: child marriage, corporal punishment, child labor, and juvenile justice. These four categories were selected based on an initial review of areas in which the US does not comply with the Convention on the Rights of the Child at the federal level and where the Convention has established age-based or otherwise measurable metrics to compare specific state laws against. The assessment did not attempt a comprehensive review of all rights covered by the Convention.

Human Rights Watch developed its scorecard in cooperation with several partner organizations, including Unchained at Last, which focuses on child marriage; the End Violence Partnership, which tracks corporal punishment laws; the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, which works to end life without parole sentences for child offenders; Human Rights for Kids, which works on juvenile justice in the United States; and Lawyers for Good Government and the Child Labor Coalition, which both work on child labor.

“State laws leave millions of children vulnerable to child marriage, violence, and exploitation,” Becker said. “While some states do better than others, all states can improve their laws to keep children safe and help them thrive.”