Understanding the long-run effects of Africa’s slave trades

Nathan Nunn

27 February 2017

Evidence suggests that Africa's slave trades played an important part in the shaping of the continent not only in terms of economic outcomes, but cultural and social outcomes as well. This column, taken from a recently published VoxEU eBook, summarises studies that reveal the lasting toxic effects of Africa’s four waves of slave trades on contemporary development.

Editor's note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the Vox eBook, The Long Economic and Political Shadow of History, Volume 2, available to download here.

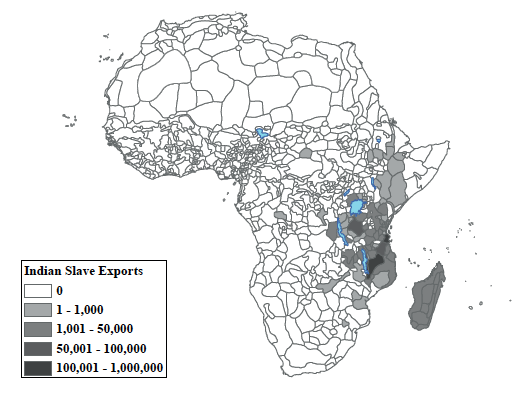

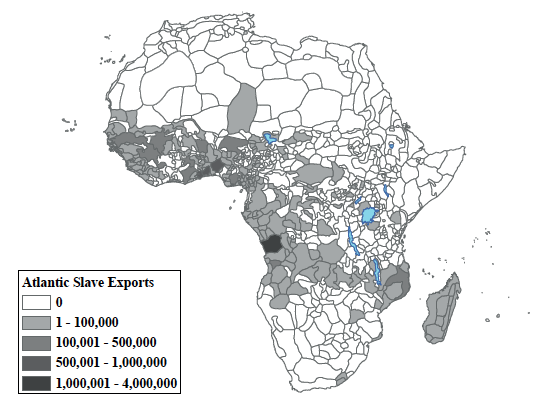

Between 1400 and 1900, the African continent experienced four sizeable slave trades. The largest and best-known was the trans-Atlantic slave trade where, beginning in the 15th century, slaves were shipped from West Africa, West Central Africa, and Eastern Africa to the European colonies in the New World. The three other slave trades – the trans-Saharan, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean slave trades – were smaller in scale and predated the trans-Atlantic slave trade. During the trans-Saharan slave trade, slaves were taken from south of the Saharan desert and shipped to Northern Africa. In the Red Sea slave trade, slaves were taken from inland of the Red Sea and shipped to the Middle East and India. In the Indian Ocean slave trade, slaves were taken from Eastern Africa and shipped either to the Middle East, India, or the plantation islands in the Indian Ocean. In total, close to 20 million slaves were taken from the continent (Nunn 2008). According to the best estimates, by 1800 Africa’s population was half of what it would have been, had the slave trades not occurred (Manning 1990).

Slaves were captured through kidnappings, raids, and warfare. A summary of the method of enslavement among a sample of 144 former slaves is provided in Table 1. Historical accounts suggest that the pervasive insecurity, violence and warfare had detrimental impacts on the institutional, social, and economic development of societies. There are numerous examples of the slave trades causing the deterioration of domestic legal institutions, the weakening of states, and political and social fragmentation (e.g. Inikori 2000, 2003, Heywood 2009).

Table 1. The methods of enslavement of Koelle’s Informants

Notes: The data are from Sigismund Koelle’s Linguistic Inventory. The sample consists of 144 informants, interviewed by Koelle, for which their means of enslavement is known.

The most illustrative example of this is the experience of the Kongo Kingdom, which was contacted in 1493 by Diogo Cao. Initially, a diverse array of products was traded between the Kongo Kingdom and the Portuguese, including copper, textiles, ivory, and slaves. At first, the only slaves to be traded were prisoners of war and criminals. However, the Portuguese demand for slaves, the pervasiveness of slave traders and merchants, and competition for the throne within the Kingdom all resulted in a dramatic and uncontrollable increase in slave capture and raiding throughout the Kingdom. By 1514, King Afonso (the Kongo King) had already written to the King of Portugal, complaining that the Portuguese merchants were colluding with noblemen to illegally enslave Kongolese citizens. In 1526, in an effort to end the trade, King Afonso requested the removal of all Portuguese merchants. In the end, his efforts were unsuccessful. Large scale slave-raiding continued unchecked into the 16th century, when it culminated in the Jaga invasion of 1568-1570. Large-scale civil war ensued from 1665-1709, resulting in the collapse of the once-powerful Kingdom (Heywood 2009).

An empirical literature has emerged that aims to supplement these historical accounts with quantitative estimates of the long-run impact of Africa’s slave trades. The first paper that attempted to provide such estimates was Nunn (2008). In the study, I undertook an empirical test, with the following logic. If the slave trades are partly responsible for Africa’s current underdevelopment, then, looking across different parts of Africa, one should observe that the areas that are the poorest today should also be the areas from which the largest number of slaves were taken in the past.

To undertake this study, I had to first construct estimates of the number of slaves taken from each country in Africa during the slave trades (i.e. between 1400 and 1900).

These estimates were constructed by combining data on the number of slaves shipped from each African port or region with data from historical documents that reported the ethnicity of over 106,000 slaves taken from Africa. Figure 1 provides an image showing a typical page from these historical documents. The documents shown are slave manumission records from Zanzibar. Each row reports information for one slave, including his/her name, ethnicity, age, and so on.

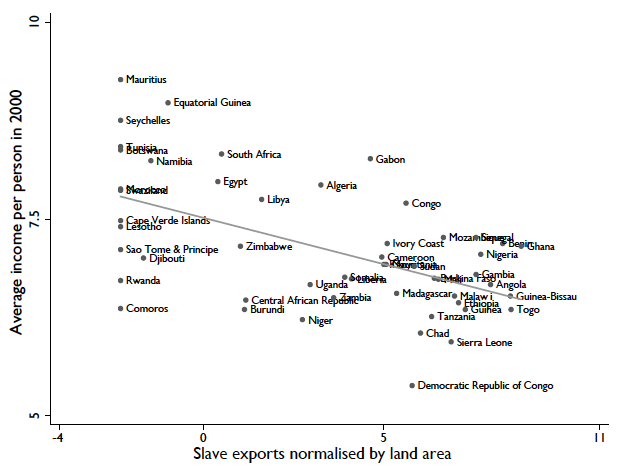

After constructing the estimates and connecting these with measures of modern day economic development, I found that, indeed, the countries from which the most slaves had been taken (taking into account differences in country size) were today the poorest in Africa. This can be seen in Figure 2, which is taken from Nunn (2008). It shows the relationship between the number of slaves taken between 1400 and 1900 and average real per capita GDP measured in 2000. As the figure clearly shows, the relationship is extremely strong. Furthermore, the relationship remains robust when many other key determinants of economic development are taken into account.

Nathan Nunn

27 February 2017

Evidence suggests that Africa's slave trades played an important part in the shaping of the continent not only in terms of economic outcomes, but cultural and social outcomes as well. This column, taken from a recently published VoxEU eBook, summarises studies that reveal the lasting toxic effects of Africa’s four waves of slave trades on contemporary development.

Editor's note: This column first appeared as a chapter in the Vox eBook, The Long Economic and Political Shadow of History, Volume 2, available to download here.

Between 1400 and 1900, the African continent experienced four sizeable slave trades. The largest and best-known was the trans-Atlantic slave trade where, beginning in the 15th century, slaves were shipped from West Africa, West Central Africa, and Eastern Africa to the European colonies in the New World. The three other slave trades – the trans-Saharan, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean slave trades – were smaller in scale and predated the trans-Atlantic slave trade. During the trans-Saharan slave trade, slaves were taken from south of the Saharan desert and shipped to Northern Africa. In the Red Sea slave trade, slaves were taken from inland of the Red Sea and shipped to the Middle East and India. In the Indian Ocean slave trade, slaves were taken from Eastern Africa and shipped either to the Middle East, India, or the plantation islands in the Indian Ocean. In total, close to 20 million slaves were taken from the continent (Nunn 2008). According to the best estimates, by 1800 Africa’s population was half of what it would have been, had the slave trades not occurred (Manning 1990).

Slaves were captured through kidnappings, raids, and warfare. A summary of the method of enslavement among a sample of 144 former slaves is provided in Table 1. Historical accounts suggest that the pervasive insecurity, violence and warfare had detrimental impacts on the institutional, social, and economic development of societies. There are numerous examples of the slave trades causing the deterioration of domestic legal institutions, the weakening of states, and political and social fragmentation (e.g. Inikori 2000, 2003, Heywood 2009).

Table 1. The methods of enslavement of Koelle’s Informants

Notes: The data are from Sigismund Koelle’s Linguistic Inventory. The sample consists of 144 informants, interviewed by Koelle, for which their means of enslavement is known.

The most illustrative example of this is the experience of the Kongo Kingdom, which was contacted in 1493 by Diogo Cao. Initially, a diverse array of products was traded between the Kongo Kingdom and the Portuguese, including copper, textiles, ivory, and slaves. At first, the only slaves to be traded were prisoners of war and criminals. However, the Portuguese demand for slaves, the pervasiveness of slave traders and merchants, and competition for the throne within the Kingdom all resulted in a dramatic and uncontrollable increase in slave capture and raiding throughout the Kingdom. By 1514, King Afonso (the Kongo King) had already written to the King of Portugal, complaining that the Portuguese merchants were colluding with noblemen to illegally enslave Kongolese citizens. In 1526, in an effort to end the trade, King Afonso requested the removal of all Portuguese merchants. In the end, his efforts were unsuccessful. Large scale slave-raiding continued unchecked into the 16th century, when it culminated in the Jaga invasion of 1568-1570. Large-scale civil war ensued from 1665-1709, resulting in the collapse of the once-powerful Kingdom (Heywood 2009).

An empirical literature has emerged that aims to supplement these historical accounts with quantitative estimates of the long-run impact of Africa’s slave trades. The first paper that attempted to provide such estimates was Nunn (2008). In the study, I undertook an empirical test, with the following logic. If the slave trades are partly responsible for Africa’s current underdevelopment, then, looking across different parts of Africa, one should observe that the areas that are the poorest today should also be the areas from which the largest number of slaves were taken in the past.

To undertake this study, I had to first construct estimates of the number of slaves taken from each country in Africa during the slave trades (i.e. between 1400 and 1900).

These estimates were constructed by combining data on the number of slaves shipped from each African port or region with data from historical documents that reported the ethnicity of over 106,000 slaves taken from Africa. Figure 1 provides an image showing a typical page from these historical documents. The documents shown are slave manumission records from Zanzibar. Each row reports information for one slave, including his/her name, ethnicity, age, and so on.

After constructing the estimates and connecting these with measures of modern day economic development, I found that, indeed, the countries from which the most slaves had been taken (taking into account differences in country size) were today the poorest in Africa. This can be seen in Figure 2, which is taken from Nunn (2008). It shows the relationship between the number of slaves taken between 1400 and 1900 and average real per capita GDP measured in 2000. As the figure clearly shows, the relationship is extremely strong. Furthermore, the relationship remains robust when many other key determinants of economic development are taken into account.

Those Europeans truly fukked yo everything

Those Europeans truly fukked yo everything