get these nets

Veteran

Through the Perilous Fight: Marine Corps Veteran Unearths Family History of Freedom Fighting

Marine veteran Taniki Richard was born and raised in the United States by Trinidadian parents. She remembers growing up surrounded by West Indian culture. The aroma of Trinidadian curry, the sounds of her dad’s steel drum, and the melody of her parents’ Trinidadian stories and lullabies enriched her childhood.

“When I was growing up, our home was like being in Trinidad,” Taniki said. “I was Americanized in the public schools. Once I opened the front door, I left Trinidad and went to America.”

Taniki enlisted in the U.S. Marines out of high school in California and proudly served her country — the country that welcomed her parents from Trinidad years before. She thought of herself as a Trinidadian-American, born of parents who migrated here from Trinidad before her birth.

Taniki’s parents taught her that “we’re all of one heart,” and she found it easy to get along with Marine brothers and sisters from diverse backgrounds, whether they had longer histories on American soil, or thought of themselves as “newer” Americans, as she did.

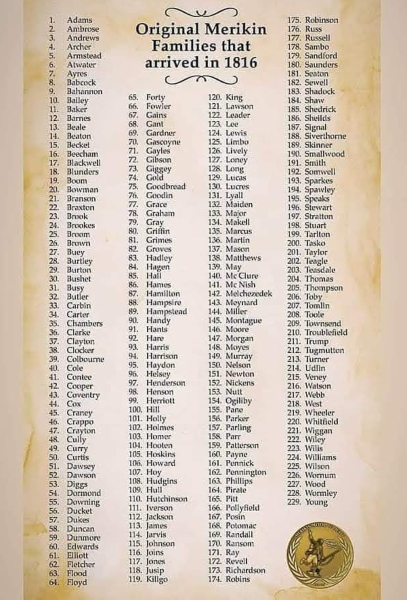

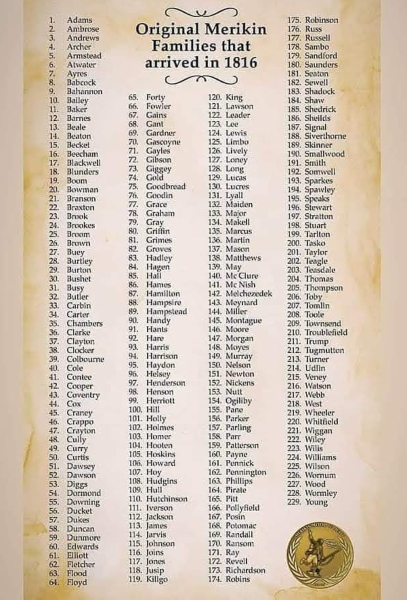

She thought of herself as a new American until she learned about her connection to free African Americans known as “Merikins” in Trinidad. About 800 people, most of whom were members of the British Colonial Marines, were relocated from the U.S. and Canada to Trinidad starting in 1815. Among them was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather who had been enslaved in Georgia and fought in the War of 1812 on the British side in exchange for freedom.

Taniki’s self-image as a new American is evolving as she unearths her father’s roots in the U.S., dating back to the 1790s. It turns out Taniki has deeper roots in the United States than she once thought. With help from her father’s sister, Victoria Simon-Holas, she is uncovering her family’s rich history one document at a time.

A birth certificate from a great-grandmother, a reparations claim from a Georgia planter, and historical records all point to a yet unnamed ancestor (one of the enslaved people on the planter’s claim). Victoria and Taniki are searching for the name of Augustus Cooper’s father. Augustus was Taniki’s great-great-grandfather and the first Trinidadian-born ancestor who inherited land in one of the areas where the Merikins settled.

Although she does not know all the details yet, Taniki nor her ancestor had easy choices.

Taniki’s ancestor had to choose between the uncertainty of life as an enslaved man — where a master would decide his fate and that of his family — or a vague offer of freedom and land after serving alongside the British. He didn’t know if he would survive the war, or if the British would make good on their promise.

By taking a big leap and sailing away with the British Colonial Marines, Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather was granted freedom, land in Trinidad, and the right to pass on that freedom and land to his descendants.

How the British Colonial Marines Became the Merikins in Trinidad

The British had courted African American soldiers (free and enslaved) since the Revolutionary War. More than two decades later, the British used the same tactics. They recruited faster than the Americans, who were reluctant to arm Black soldiers.

British ships would come into American harbors like Chesapeake Bay, where they would set up camp on Tangier Island and issue invitations to enslaved people in nearby plantations, and to those who ran away and had made it to the area. They also did this in the South, coming to Cumberland Island, Georgia.

The new settlers made it to Trinidad in separate voyages between 1815 and 1816. Back in the U.S., planters claimed damages by itemizing each “runaway slave” to receive reparations from the British. Meanwhile, the new inhabitants had to contend with 16 acres of virgin forest to clear, a small provision of food the first year, and seeds to plant crops on their new land.

One of those pioneers was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather. Records show he passed land to his son Augustus Cooper, who was successful in planting cocoa.

The relocated soldiers organized into companies, much like they did in the military. They retained the discipline and structure that got them through the war. Their legacy still lives on in the names of parishes and streets in present-day Trinidad. Through the years, they retained their Baptist faith and their identity as “Merikins” as they came to be known in their new home.

.

Marine veteran Taniki Richard was born and raised in the United States by Trinidadian parents. She remembers growing up surrounded by West Indian culture. The aroma of Trinidadian curry, the sounds of her dad’s steel drum, and the melody of her parents’ Trinidadian stories and lullabies enriched her childhood.

“When I was growing up, our home was like being in Trinidad,” Taniki said. “I was Americanized in the public schools. Once I opened the front door, I left Trinidad and went to America.”

Taniki enlisted in the U.S. Marines out of high school in California and proudly served her country — the country that welcomed her parents from Trinidad years before. She thought of herself as a Trinidadian-American, born of parents who migrated here from Trinidad before her birth.

Taniki’s parents taught her that “we’re all of one heart,” and she found it easy to get along with Marine brothers and sisters from diverse backgrounds, whether they had longer histories on American soil, or thought of themselves as “newer” Americans, as she did.

She thought of herself as a new American until she learned about her connection to free African Americans known as “Merikins” in Trinidad. About 800 people, most of whom were members of the British Colonial Marines, were relocated from the U.S. and Canada to Trinidad starting in 1815. Among them was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather who had been enslaved in Georgia and fought in the War of 1812 on the British side in exchange for freedom.

Taniki’s self-image as a new American is evolving as she unearths her father’s roots in the U.S., dating back to the 1790s. It turns out Taniki has deeper roots in the United States than she once thought. With help from her father’s sister, Victoria Simon-Holas, she is uncovering her family’s rich history one document at a time.

A birth certificate from a great-grandmother, a reparations claim from a Georgia planter, and historical records all point to a yet unnamed ancestor (one of the enslaved people on the planter’s claim). Victoria and Taniki are searching for the name of Augustus Cooper’s father. Augustus was Taniki’s great-great-grandfather and the first Trinidadian-born ancestor who inherited land in one of the areas where the Merikins settled.

Although she does not know all the details yet, Taniki nor her ancestor had easy choices.

Taniki’s ancestor had to choose between the uncertainty of life as an enslaved man — where a master would decide his fate and that of his family — or a vague offer of freedom and land after serving alongside the British. He didn’t know if he would survive the war, or if the British would make good on their promise.

By taking a big leap and sailing away with the British Colonial Marines, Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather was granted freedom, land in Trinidad, and the right to pass on that freedom and land to his descendants.

How the British Colonial Marines Became the Merikins in Trinidad

The British had courted African American soldiers (free and enslaved) since the Revolutionary War. More than two decades later, the British used the same tactics. They recruited faster than the Americans, who were reluctant to arm Black soldiers.

British ships would come into American harbors like Chesapeake Bay, where they would set up camp on Tangier Island and issue invitations to enslaved people in nearby plantations, and to those who ran away and had made it to the area. They also did this in the South, coming to Cumberland Island, Georgia.

The new settlers made it to Trinidad in separate voyages between 1815 and 1816. Back in the U.S., planters claimed damages by itemizing each “runaway slave” to receive reparations from the British. Meanwhile, the new inhabitants had to contend with 16 acres of virgin forest to clear, a small provision of food the first year, and seeds to plant crops on their new land.

One of those pioneers was Taniki’s great-great-great-grandfather. Records show he passed land to his son Augustus Cooper, who was successful in planting cocoa.

The relocated soldiers organized into companies, much like they did in the military. They retained the discipline and structure that got them through the war. Their legacy still lives on in the names of parishes and streets in present-day Trinidad. Through the years, they retained their Baptist faith and their identity as “Merikins” as they came to be known in their new home.

.

We're nearing the twilight zone

We're nearing the twilight zone