Scustin Bieburr

Baby baybee baybee UUUGH

It's a vast work that I can't fit into one post, so I'm breaking it down into multiple. I'll be highlighting the parts that are especially important and relevant to us now.

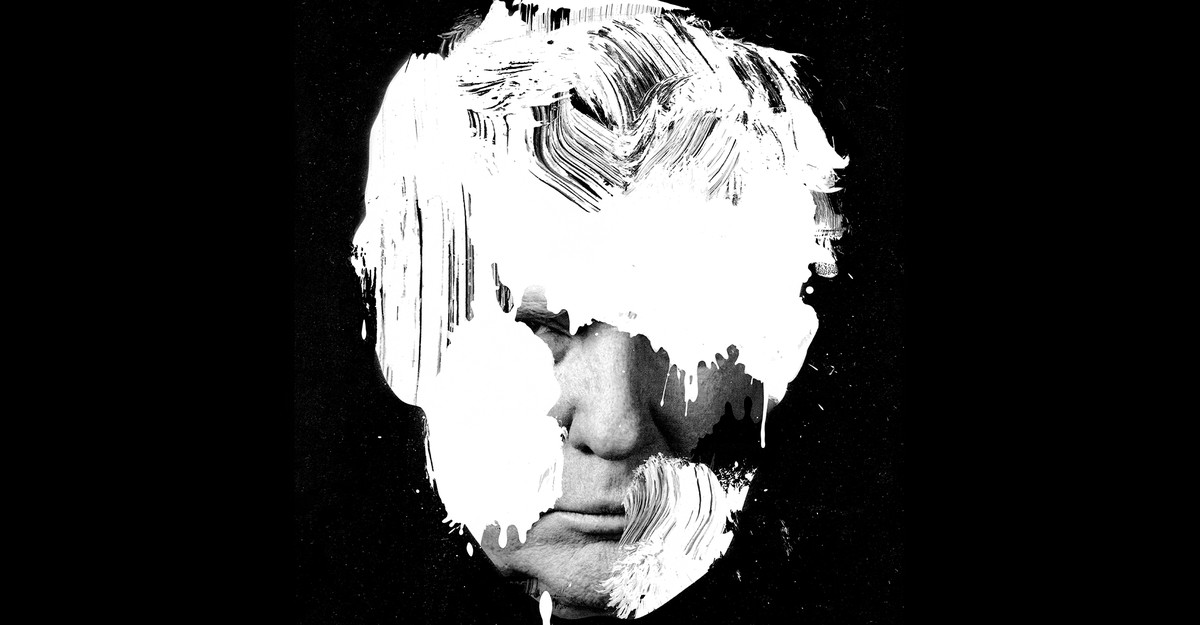

It is insufficient to state the obvious of Donald Trump: that he is a white man who would not be president were it not for this fact. With one immediate exception, Trump’s predecessors made their way to high office through the passive power of whiteness—that bloody heirloom which cannot ensure mastery of all events but can conjure a tailwind for most of them. Land theft and human plunder cleared the grounds for Trump’s forefathers and barred it for others. Once upon the field, these men became soldiers, statesmen, and scholars, held court in Paris, presided at Princeton, advanced into the Wilderness and then into the White House. Their individual triumphs made this exclusive party seem above America’s founding sins, and it was forgotten that the former was in fact bound to the latter, that all their victories had transpired on cleared grounds. No such elegant detachment can be attributed to Donald Trump—a president who, more than any other, has made the awful inheritance explicit.

His political career began in advocacy of birtherism, that modern recasting of the old American precept that black people are not fit to be citizens of the country they built. But long before birtherism, Trump had made his worldview clear. He fought to keep blacks out of his buildings, called for the death penalty for the eventually exonerated Central Park Five, and railed against “lazy” black employees. “Black guys counting my money! I hate it,” Trump was once quoted as saying. “The only kind of people I want counting my money are short guys that wear yarmulkes every day.” After his cabal of conspiracy theorists forced President Obama to present his birth certificate, Trump then demanded the president’s college grades (offering $5 million in exchange for them), insisting that Obama was not intelligent enough to have gone to an Ivy League university, and that his acclaimed memoir Dreams from My Father had been ghostwritten by a white man, Bill Ayers. While running for president Trump vented his displeasure at a judge presiding over a pair of cases in which he was a defendant. “He’s a Mexican,” Trump protested.

It is often said that Trump has no real ideology, which is not true—his ideology is white supremacy in all of its truculent and sanctimonious power. Trump inaugurated his campaign by casting himself as the defender of white maidenhood against Mexican “rapists,” only to be later revealed as a proud violator. White supremacy has always had a perverse sexual tint. It is thus appropriate that Trump’s rise was shepherded by Steve Bannon, a man who mocks his white male opponents as “cucks.” The word, derived from cuckold, is specifically meant to debase by fear/fantasy—the target is so weak that he would submit to the humiliation of having his white wife lie with black men. That the slur cuck casts white men as victims aligns with the dictums of whiteness, which seek to alchemize one’s profligate sins into virtue. So it was with Virginia slaveholders claiming that Britain sought to make slaves of them. So it was with rapacious Klansmen organized against alleged outrages. So it was with a candidate who called for a foreign power to hack his opponent’s email and a president now claiming to be the victim of “the single greatest witch hunt of a politician in American history.”

In Trump, white supremacists see one of their own. He denounced David Duke and the Ku Klux Klan, grudgingly. Bannon bragged that Breitbart News, the site he once published, was the preferred “platform” for the white supremacist “alt-right” movement. The alt-right’s preferred actual home is Russia, which its leaders hail as “the great white power” and the specific power that helped ensure the election of Donald Trump.

To Trump whiteness is neither notional nor symbolic but is the very core of his power. In this, Trump is not singular. But whereas his forebears carried whiteness like an ancestral talisman, Trump cracked the glowing amulet open, releasing its eldritch energies. The repercussions are striking: Trump is the first president to have served in no public capacity before ascending to his perch. Perhaps more important, Trump is the first president to have publicly affirmed that his daughter is a “piece of ass.” The mind seizes trying to imagine a black man extolling the virtues of sexual assault on tape (“And when you’re a star, they let you do it”), fending off multiple accusations of said assaults, becoming immersed in multiple lawsuits for allegedly fraudulent business dealings, exhorting his followers to violence, and then strolling into the White House. But that is the point of white supremacy—to ensure that that which all others achieve with maximal effort, white people (and particularly white men) achieve with minimal qualification. Barack Obama delivered to black people the hoary message that in working twice as hard as white people, anything is possible. But Trump’s counter is persuasive—work half as hard as black people and even more is possible.

A relationship between these two notions is as necessary as the relationship between these two men. It is almost as if the fact of Obama, the fact of a black president, insulted Trump personally. The insult redoubled when Obama and Seth Meyers publicly humiliated Trump at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2011. But the bloody heirloom ensures the last laugh. Replacing Obama is not enough—Trump has made the negation of Obama’s legacy the foundation of his own. And this too is whiteness. “Race is an idea, not a fact,” writes the historian Nell Irvin Painter, and essential to the construct of a “white race” is the idea of not being a ******. Before Barack Obama, ******s could be manufactured out of Sister Souljahs, Willie Hortons, Dusky Sallys, and Miscegenation Balls. But Donald Trump arrived in the wake of something more potent—an entire ****** presidency with ****** health care, ****** climate accords, ****** justice reform that could be targeted for destruction, that could be targeted for redemption, thus reifying the idea of being white. Trump truly is something new—the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president. And so it will not suffice to say Trump is a white man like all the others who rose to become president. He must be called by his correct name and rightful honorific—America’s first white president.

It is insufficient to state the obvious of Donald Trump: that he is a white man who would not be president were it not for this fact. With one immediate exception, Trump’s predecessors made their way to high office through the passive power of whiteness—that bloody heirloom which cannot ensure mastery of all events but can conjure a tailwind for most of them. Land theft and human plunder cleared the grounds for Trump’s forefathers and barred it for others. Once upon the field, these men became soldiers, statesmen, and scholars, held court in Paris, presided at Princeton, advanced into the Wilderness and then into the White House. Their individual triumphs made this exclusive party seem above America’s founding sins, and it was forgotten that the former was in fact bound to the latter, that all their victories had transpired on cleared grounds. No such elegant detachment can be attributed to Donald Trump—a president who, more than any other, has made the awful inheritance explicit.

His political career began in advocacy of birtherism, that modern recasting of the old American precept that black people are not fit to be citizens of the country they built. But long before birtherism, Trump had made his worldview clear. He fought to keep blacks out of his buildings, called for the death penalty for the eventually exonerated Central Park Five, and railed against “lazy” black employees. “Black guys counting my money! I hate it,” Trump was once quoted as saying. “The only kind of people I want counting my money are short guys that wear yarmulkes every day.” After his cabal of conspiracy theorists forced President Obama to present his birth certificate, Trump then demanded the president’s college grades (offering $5 million in exchange for them), insisting that Obama was not intelligent enough to have gone to an Ivy League university, and that his acclaimed memoir Dreams from My Father had been ghostwritten by a white man, Bill Ayers. While running for president Trump vented his displeasure at a judge presiding over a pair of cases in which he was a defendant. “He’s a Mexican,” Trump protested.

It is often said that Trump has no real ideology, which is not true—his ideology is white supremacy in all of its truculent and sanctimonious power. Trump inaugurated his campaign by casting himself as the defender of white maidenhood against Mexican “rapists,” only to be later revealed as a proud violator. White supremacy has always had a perverse sexual tint. It is thus appropriate that Trump’s rise was shepherded by Steve Bannon, a man who mocks his white male opponents as “cucks.” The word, derived from cuckold, is specifically meant to debase by fear/fantasy—the target is so weak that he would submit to the humiliation of having his white wife lie with black men. That the slur cuck casts white men as victims aligns with the dictums of whiteness, which seek to alchemize one’s profligate sins into virtue. So it was with Virginia slaveholders claiming that Britain sought to make slaves of them. So it was with rapacious Klansmen organized against alleged outrages. So it was with a candidate who called for a foreign power to hack his opponent’s email and a president now claiming to be the victim of “the single greatest witch hunt of a politician in American history.”

In Trump, white supremacists see one of their own. He denounced David Duke and the Ku Klux Klan, grudgingly. Bannon bragged that Breitbart News, the site he once published, was the preferred “platform” for the white supremacist “alt-right” movement. The alt-right’s preferred actual home is Russia, which its leaders hail as “the great white power” and the specific power that helped ensure the election of Donald Trump.

To Trump whiteness is neither notional nor symbolic but is the very core of his power. In this, Trump is not singular. But whereas his forebears carried whiteness like an ancestral talisman, Trump cracked the glowing amulet open, releasing its eldritch energies. The repercussions are striking: Trump is the first president to have served in no public capacity before ascending to his perch. Perhaps more important, Trump is the first president to have publicly affirmed that his daughter is a “piece of ass.” The mind seizes trying to imagine a black man extolling the virtues of sexual assault on tape (“And when you’re a star, they let you do it”), fending off multiple accusations of said assaults, becoming immersed in multiple lawsuits for allegedly fraudulent business dealings, exhorting his followers to violence, and then strolling into the White House. But that is the point of white supremacy—to ensure that that which all others achieve with maximal effort, white people (and particularly white men) achieve with minimal qualification. Barack Obama delivered to black people the hoary message that in working twice as hard as white people, anything is possible. But Trump’s counter is persuasive—work half as hard as black people and even more is possible.

A relationship between these two notions is as necessary as the relationship between these two men. It is almost as if the fact of Obama, the fact of a black president, insulted Trump personally. The insult redoubled when Obama and Seth Meyers publicly humiliated Trump at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in 2011. But the bloody heirloom ensures the last laugh. Replacing Obama is not enough—Trump has made the negation of Obama’s legacy the foundation of his own. And this too is whiteness. “Race is an idea, not a fact,” writes the historian Nell Irvin Painter, and essential to the construct of a “white race” is the idea of not being a ******. Before Barack Obama, ******s could be manufactured out of Sister Souljahs, Willie Hortons, Dusky Sallys, and Miscegenation Balls. But Donald Trump arrived in the wake of something more potent—an entire ****** presidency with ****** health care, ****** climate accords, ****** justice reform that could be targeted for destruction, that could be targeted for redemption, thus reifying the idea of being white. Trump truly is something new—the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president. And so it will not suffice to say Trump is a white man like all the others who rose to become president. He must be called by his correct name and rightful honorific—America’s first white president.

Last edited:

- that white supremacy can't really be a problem for us because our 'greatest' contemporary black writers/ spokespeople can only see it when it's wearing a MAGA hat. It starts to look more like partisanship than actual grievance.

- that white supremacy can't really be a problem for us because our 'greatest' contemporary black writers/ spokespeople can only see it when it's wearing a MAGA hat. It starts to look more like partisanship than actual grievance.