This 'Holy Grail' Protein Repairs DNA And Could Lead to a Cancer Vaccine

Scientists have discovered a protein that can directly halt DNA damage.

This 'Holy Grail' Protein Repairs DNA And Could Lead to a Cancer Vaccine

Health26 August 2024

By Michael Irving

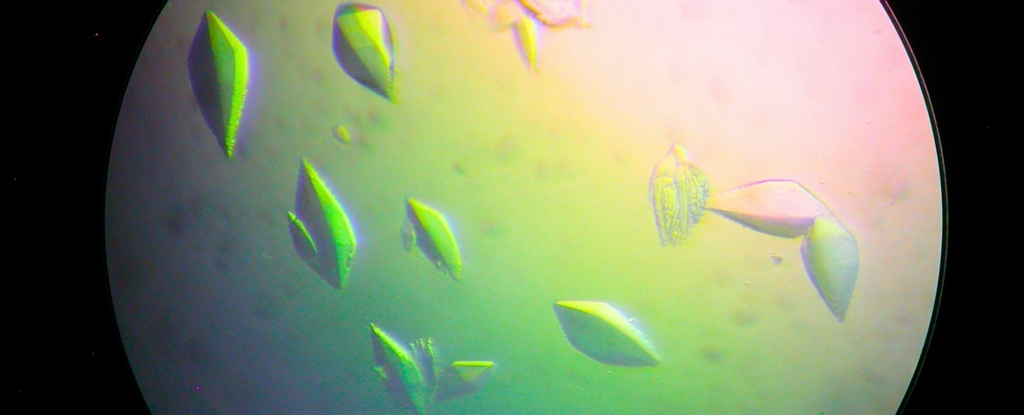

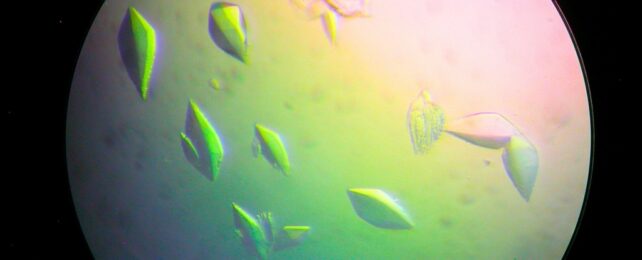

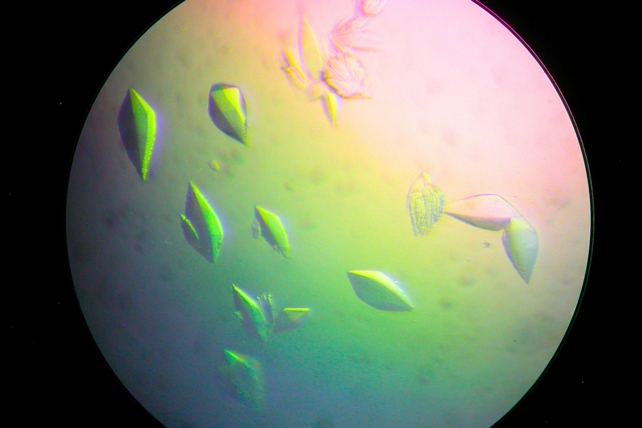

A DNA-repairing protein has been discovered in bacteria. (Canadian Light Source)

Scientists have discovered a protein that can directly halt DNA damage. Better yet, a new study shows it appears to be 'plug and play', theoretically able to slot into any organism, making it a promising candidate for a cancer vaccine.

DNA damage response protein C (DdrC) was found in a hardy little bacterium called Deinococcus radiodurans. DdrC seems to be very effective at detecting DNA damage, putting a stop to it and alerting the cell to start the repair process.

But DdrC's best feature might be that it's pretty self-contained, doing its job without the help of other proteins.

It should be relatively easy to transfer the ddrC gene into almost any other organism to improve DNA repair systems, as researchers from Western University in Canada discovered when they plugged it into boring old E. coli.

"To our huge surprise, it actually made the bacterium over 40 times more resistant to UV radiation damage," says biochemist Robert Szabla, the first author of the new paper.

"This seems to be a rare example where you have one protein and it really is like a standalone machine."

Unchecked DNA damage can lead to a range of diseases. UV light, for instance, can damage the DNA in your skin cells, boosting the chances of skin cancer. Being able to prevent or even reverse that damage could save lives.

"The ability to rearrange and edit and manipulate DNA in specific ways is the holy grail in biotechnology," says Szabla.

"What if you had a scanning system such as DdrC which patrolled your cells and neutralized damage when it happened? This might form the basis of a potential cancer vaccine."

D. radiodurans is an obvious place to look for this kind of tool. The bacterium can survive doses of radiation thousands of times more than enough to kill a human cell.

It's been found to survive long stretches on the outside of the International Space Station, and can even survive in conditions comparable to those on the surface of Mars. It turns out DdrC plays a key role in that hardiness.

"With a human cell, if there are any more than two breaks in the entire billion base pair genome, it can't fix itself and it dies," says Szabla.

"But in the case of DdrC, this unique protein helps the cell to repair hundreds of broken DNA fragments into a coherent genome."

A DNA-repairing protein called DdrC has been discovered in D. radiodurans. (Canadian Light Source)

The researchers used the powerful X-ray beam at the Canadian Light Source to probe the 3D shape of DdrC and figure out how it works its magic.

They discovered that the protein scans along the DNA, searching for lesions on one or both strands. When it finds either a single-strand or double-strand break, it then binds to it and goes looking for another break of the same type.

Once it locates two single-strand breaks, DdrC will bind to and immobilize them both, compacting the segment of DNA. It does a similar thing with pairs of double-strand breaks, wrapping the two loose ends together to form a circle – kind of like tying a loop into a shoelace.

These fixes not only prevent the damage from getting worse, but they also signal to the cell's DNA repair mechanisms to come and patch up the breaks.

Among the many benefits of better DNA repair, adapting this mechanism could be a boon to genetic engineering, helping us develop cancer vaccines and climate-change-resistant crops. And there might be more new tools where that came from.

"DdrC is just one out of hundreds of potentially useful proteins in this bacterium," says Szabla.

"The next step is to prod further, look at what else this cell uses to fix its own genome – because we're sure to find many more tools where we have no idea how they work or how they're going to be useful until we look."

The study was published in the journal Nucleic Acids Research.